My friends, I would like to confess that I seriously considered not doing a newsletter this week and hoping no one noticed because I am less than two weeks away from delivering the draft manuscript for my next book, and I have reached the phase of the process where I am like Ken from the Barbie movie, except rather than “beach” my job is “book.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Just about every thought I have is about the book. Just about every thing I do seems to relate back to the book. I was at my weekly drum lesson and I had an epiphany about the similarities between a writer’s practice and a musician’s practice that I put into the book. While walking the dog I was listening to an episode of Marc Maron’s podcast with Jesse David Fox, author of Comedy Book: How Comedy Conquered Culture - And the Magic That Makes it Work and had another mini-epiphany about how to frame what it means to read like a writer, which had me urging little Quincy to hurry up and do his business so I could get home and capture it on the page.

This is both an exhilarating and anxiety-producing time in the book writing process. On the one hand, you start to see the whole come together, and if the whole seems pretty good, you start to feel like you’ve done something that might turn out okay.

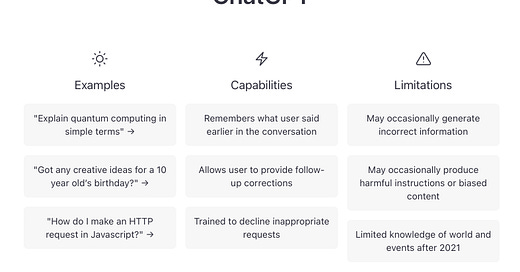

On the other hand, you’re also worried that you might’ve written a misguided piece of shit. The anxiety is a little higher this time around given that I’m writing on a subject (reading and writing in the age of AI) that is a moving target, but knowing it’s a moving target has forced me to go deep on the things that I think are really at the roots of both reading and writing, and how those actions manifest themselves in school, work, and the culture at large.

So when a meme popped up on social media this week concerning the “25 books that should be on every school curriculum but aren’t,” my brain immediately started churning in the context of the book.

Like all list-based memes this one is a mix of interesting and annoying. The first example I saw of it was from a performatively anti-woke Twitter account that has the profile of a Greek sculpture for an avatar. (An almost certain indicator you’re dealing with a huge douche.) But others were more thoughtful and interesting, providing food for thought as to how one might answer the question for themselves, and the more I thought about it, the harder it became to name specific books - whether they’re currently assigned or not - that I would say students must read.

Here I have to step back and say that I simultaneously hold reading in very high regard, while also view any framing of reading as some kind of process of moral or character formation, or the actions of a superiorly evolved person with great suspicion, even scorn. Reading is not a magic elixir by which we become good people or cultured people or whatever. It is not the only way to acquire knowledge or wisdom. (It is a good way, but not the only way.)

The reason I read is because I derive pleasure from reading. Those pleasures vary depending on the context in which I am reading, but they are always present and they are the fuel for the reading. Yes, I do a lot of reading in a professional capacity, but I have taken care to organize that professional activity around reading from which I derive pleasure. If and when those professional activities stop I will continue to read. In fact, the biggest change in my reading is likely that I will do it more.

That said, I cannot deny the influence that reading has had on my world view. I guess what I’m saying, though, is that shaping and reshaping your world view through reading is primarily a good thing because that itself is pleasurable. We don’t need to champion reading because it’s good for you. Reading is just plain good.

To the extent that students don’t know or haven’t experienced his, I blame the adults of the world.

Many of the lists of books people think students should read seem designed to troll those with different politics - say by recommending the collected works of Ayn Rand - or to demonstrate the poster’s outstanding erudition (Catullus, except also in Latin).

Even if sincere, I don’t have a ton of time for these kinds of recommendations that see students as blocks of clay which must be formed by the schools and teachers via the choice of curriculum. My preference is to view students as independent human agents who should be allowed the freedom to shape their own moral world views. For sure, schooling plays a role in that and we must be mindful of that process, but you’ll never find me telling students what to think.

This ultimately made it impossible for me to make my own list of specific books, but as I’d been working on a chapter for my book about the ways we read and where generative AI could productively substitute for some of that reading, and where I believe we must preserve the human element of reading, I started thinking differently about this list. This is what I came up with.

The books that should be on every school curriculum that may or may not be on that curriculum because it depends a lot on where you go to school.

Some books that engender laughter in the reader.

Some books that engender sadness or even grief in the reader.

Some books the reader finds difficult or even confusing.

Some books that the reader races through at a breakneck pace.

Some books that must be read slowly.

Some books that are ideally read more than once.

Some books that are written from a point of view close to that of the reader.

Some books that are written from points of view very different to that of the reader.

Some books that are surprising.

Some books that are boring.

Some books that were written a long time ago.

Some books that were written very recently.

Some books that the reader will almost certainly agree with.

Some books that the reader will almost certainly disagree with.

Some books the reader may find challenging or even insulting to their world view.

Some books that make the reader feel as though someone else deeply understand them.

Some books about the past.

Some books about the future.

Some books about the present.

Some books with animals that talk.

Some books in translation.

Some books that are poetry.

Some books where everything is made up.

Some books where nothing is made up.

Some books where everything is made up and still true.

Some books where nothing is made up but aren’t true.

This is off the top of my head. If my job wasn’t “book” right now I could probably keep going much longer. Some of you might be thinking that my list looks suspiciously like its designed to engender some kind of moral formation in the reader. To the extent this is true, let me suggest back that this sort of list gives the power for that formation to the student themselves. The goal is for the student to have reading experiences which provide them the chance to learn and reflect and reframe what they know about the world.

We should always be prepared to have our foundations rocked by something new. This is the work of being human. At the same time, we also must have a foundational critical sensibility that we can fall back on after we have been rocked.

This is what I wish for students, always.

I am curious about a couple of things from you people. One is, how you would answer the original question. Are there books that you think students should or even must read?

The second is whether or not you can think of books you’ve read that fit the different criteria in my list. How have books informed your own critical sensibilities?

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I write about the near tragedy of Warner Brothers deep-sixing the completed Coyote vs. Acme movie, based on the classic humor piece by Ian Frazier collected in his book, Coyote v. Acme.

Esquire has released its list of 20 best books of the year. Real Simple decided that the right number of best books is 60. The New York Times has the 10 best books of the year.

The Joyce Carol Oates Prize announced its longlist. The prize goes to a writer who has more than one book, but has yet to win a big award or major fellowship, which makes for an interesting list of established writers who deserve more attention.

Has the reality of student debt and online classes killed the campus novel? Kate Dwyer at Esquire ponders the question.

Following the passing of Gabe Hudson (which I wrote about last week), a bunch of AI-generated “obituaries” popped to the top of search results for those looking for information about him. In order to combat that and to give those who knew and appreciated Gabe’s contributions to the world, McSweeney’s is collecting memories and publishing them on the website. If you’d like to contribute your own, there’s an email address at this link.

Recommendations

1. A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers

2. Uprooted by Naomi Novik

3. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

4. Exhalation by Ted Chiang

5. The Seamstress and the Wind by Cesar Aira

Maria Y. - Boston, MA

Maria is a great candidate for The Complete Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino.

1. Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

2. A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers

3. My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante

4. The Thursday Murder Club by Richard Osman

5. Big Swiss by Jen Beagin

Rachelle T. - Ottawa, Canada

There’s a number of Louise Erdrich novels I have in mind here, and there’s no wrong choice, but the specific choice is The Round House.1

If it wasn’t obvious, I’m heading back to book. If you don’t see me here next week, it’s because I’ve disappeared into it entirely, but my hope is that I’ll be able to emerge into the world at large for at least a short period of time.

JW

The Biblioracle

All books linked throughout the newsletter go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and the Teacher Salary Project, which is advocating to establish a federal minimum salary for teachers of $60,000 per year. Affiliate income is $307.30 for the year.

Thanks for this, John. It’s an exciting and meaningful list, way more valuable than naming specific titles.

I’m a high school English teacher, almost halfway through year 32 in the classroom, and so nearing the very end of my career. I would add this: I want to help students see that literature is a conversation—between readers, and between readers and books, of course, but also between the books themselves. And so, I try to design each course to highlight just that. My sophomores, after working through Frankenstein, are now reading Klara and the Sun. And next week, my seniors will read Tolstoy’s “Master and Man,” and the week after that, “Tenth of December” by George Saunders. In this way, I hope they’ll see that some of the questions Mary Shelley raised two hundred years ago are ones that Kazuo Ishiguro explored two years ago. Similarly, Saunders has plumbed Tolstoy’s icy grounds and seemingly sudden transformations. These parallels can be exciting and enriching to readers not as a literary game but to illustrate that some of the questions then are the same questions now about what it means to be human.

Students should read (at least) one book that their teacher is so SO passionate about. Even if these students largely end up rolling their eyes at that teacher, there's something so wholesome, so memorable, about seeing someone deeply love a book, love reading, and teachers should model that.