Building a Creative Practice

Could it even be the key to longevity?

I think generative AI tools such as DALL-E and MidJourney for images and ChatGPT for text have scrambled people’s brains a bit. What the AI is capable of, and the way it presents its output to us is genuinely amazing and it’ll mess you up when you first see it.

When I was preparing the slides for a talk I was going to give on teaching writing in a world where this technology exists, I went to DALL-E and prompted it to give me a picture in the style of Picasso showing a teacher tearing their hair out over grading homework, and it coughed these up in like five seconds.

Holy crap! I thought. I could never do that. Even someone who could to it might not be able to do it that well, and definitely not that quickly.

Perhaps this is a tool that will unleash previously untapped creativity, for example, the ability to generate illustrations by people who cannot draw worth a lick.

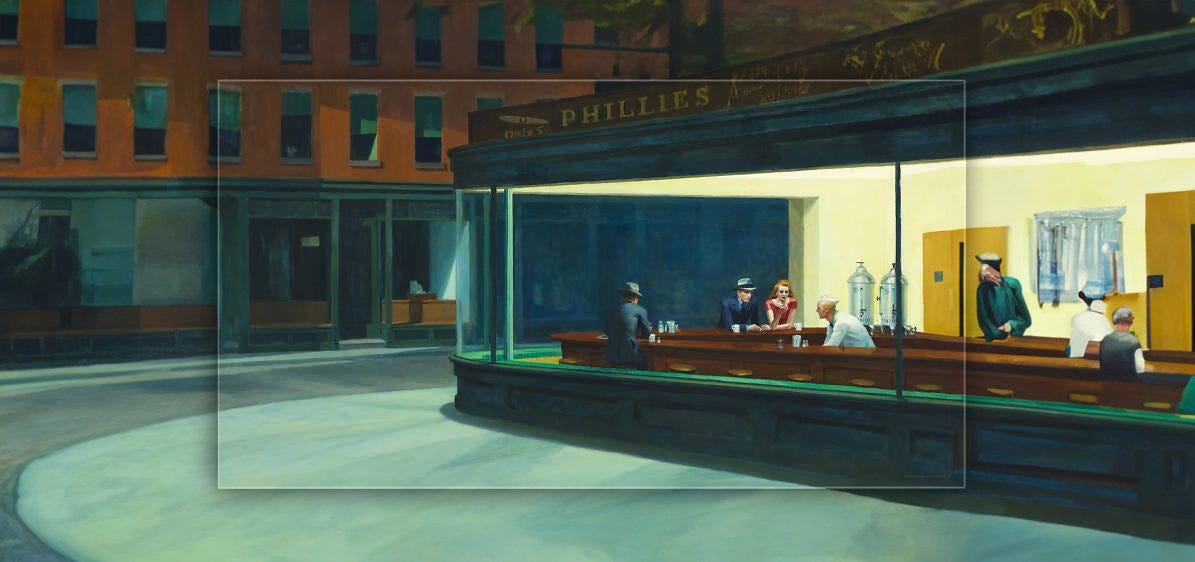

The enthusiasm for this stuff as a potential catalyst for creativity is everywhere. Many of you probably saw the gimmick of using an AI-powered engine in Adobe to “fill out the background” of famous paintings like the Mona Lisa or Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks:

I mean, okay. Wow. But also, so what? Is this something we’d consider a creative act? This tweet from Jonathan Haidt also caught my eye as he marvels at a feature in MidJourney that will generate different backgrounds as you zoom in and out of an image.

Haidt calls this a “boon to creativity,” but what is creative about it? Is playing around with the settings of an AI-generated image and backdrop a creative act?

Creativity is weird and it’s tough to talk about it. When you do talk about it, it’s easy to lapse into what I call “woo-woo,” pronouncements which sound profound in the moment, but if you think about them for a bit, your primary response is No duh.

Being creative requires no specific knowledge that I can think of. Children are inherently creative. Consider the bog standard imaginative play that any kid engages in with their toys. My older brother, now a successful lawyer, was an insanely creative kid. After a family visit to Disney World when I was four and he was eight, he recreated Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride in our basement, including flames licking up from the title floor and low hanging bridge gates that threatened to decapitate the rider. (Me perched on a chair, holding a hockey stick at neck height.)

As adults, given my work, I’m supposedly the creative one, but no one would’ve said that when we were kids, and if you asked him, he’d probably be able to tell you the ways thinking creatively have helped him professionally.

But I’m still stuck. If we’re not going to judge creativity by the outcome of a particular act that generates a painting, picture, poem, song, story, etc…how do we recognize its existence?

Not coincidentally to these thoughts I’ve been reading legendary music producer Rick Rubin’s The Creative Act: A Way of Being. Rubin carries himself with an air of the mystic or guru, the long beard, never wearing shoes, refusing to work behind a desk, not even knowing how to operate the equipment in a recording studio, while being the most influential record producer of the last 50 years.

One would think that a book on creativity by someone with the persona of Rick Rubin would have a lot of woo-woo in it, and it does. The chapters are short and organized around conceptual themes such as “Tuning In,” “Rules,” or “Surrounding the Lightning Bolt.” At the end of many chapters, Rubin shares a brief, koan-like poem on the theme, like this one in the chapter on “Awareness”:

The ability to look deeply is the root of creativity. To see past the ordinary and mundane and get to what otherwise might be invisible.

Yeah, no shit, Rick. Tell us something we don’t already know, like how to actually achieve that.

Fortunately, that’s pretty much what the non woo-woo parts of the book do. Individually and collectively the insights Rubin shares paints a portrait of his personal creative “practice.”

I’m a big fan of the framework of a “practice,” which is why my book of writing experiences is called The Writer’s Practice. A practice is the skills, attitudes, knowledge, and habits of mind of the practitioner. Just about any activity you can think of can be broken down into the component parts of a practice: writer, musician, painter, lawyer, doctor, parent, groundskeeper, mechanic, etc…etc…

These different dimensions of a practice always interact and often overlap. For example, a chef’s practice relies on the physical skills and techniques of cooking combined with the knowledge of how employing those techniques creates certain results in the food.

Thinking about these things through the lens of practice cuts through a lot of the woo-woo, and much of what I focus on with students is asking them to be conscious of how their practices are building as they write, as they practice their practices.

The subtitle of Rubin’s book, A Way of Being, indicates that much of the focus of Rubin’s practice is rooted in his habits of mind, which seem to drive his creative process. Rick Rubin has gotten very comfortable being Rick Rubin, and it shows in the work he produces.

To that end, for me, the book is primarily inspirational or perhaps aspirational, as opposed to practical. It would be awesome to get to the place Rick Rubin is in terms of living one’s life through a creative practice, but you know, it’s tough, most of us have bills that don’t get paid by intuiting what kind of production works best for a particular song.

That said, one thing I think the book makes clear is that while Rick Rubin may be a “genius,” that genius is something that must be literally cultivated.

If there’s anything I tried to impress on my talented students, it’s this. Yes, sometimes great stuff will come to you like a bolt from the blue, but if you want that to happen, there’s lots of things that help make you more attractive to the gods above hurling a lightning bolt your way.

I’ve never known a successful writer who sits around waiting for inspiration. They go out and seek it. They walk around a field in a lightning storm wearing a knight’s suit of armor holding a fifty foot long metal poll in one hand and flying a kite with a key attached to the other.

If you’re looking for a book that wholly demystifies the creative practice, I recommend a book I’ve talked about here before by friend of the newsletter Austin Kleon Steal Like an Artist.

What I like about Austin’s book is that it is filled with very practical, straightforward things you can do to help practice being creative, to prime the pump of your own imagination and creative practice. Every writing course I taught after I read his book recommended that students start what he calls a “swipe folder” where you put the stuff you like that you might want to steal someday.

Of course he doesn’t mean steal as in plagiarize, but as a source of inspiration, an example of the kind of art you might want to make. Starting with art that is in some ways an imitation of the work you love is a very good way to get a creative practice rolling.

Over time, those influences become diluted in your practice as other influences come in, and as you figure out what you sound like on the page. William Faulkner leaked out of Cormac McCarthy’s oeuvre over time, though some of that spirit was ever present. The Beatles started by playing covers of their favorite rhythm and blues artists and in no time at all, they were The Beatles.

The reason why typing prompts into MidJourney or DALL-E and looking at the result and thinking “that’s cool” is not a creative act is because there is no practice behind it. Generative AI algorithms cranking away on their predictive models is not creativity.

There are many very practical things you can do to build a creative practice. For me, routine helps. When I was in grad school, my routine became very patterned. Teaching in the morning, my classes in the afternoon, a nap and then 2-3 hours of writing into the early evening. After writing, my friend Nick would bring his dog over to play with my dog in an open field across the street from my apartment. After that, some dinner, reading or other schoolwork or paper grading and bed. I wrote 400,000 words of fiction over the course of three years with that routine.

Sleep is necessary, as is other downtime, and that doesn’t mean scrolling on Twitter or playing the New York Times Spelling Bee, two things I spend a fair amount of time on. It means literal downtime. When I’m in the midst of a project at some point each day you will find me flat on my back on the couch in my office, eyes closed, trying not to consciously think of anything. This sometimes segues into a catnap.

It is hard to convince people who work in a different way that laying flat on your back with your eyes closed is an integral part of your process, and I frequently feel guilt or chagrin over this part of my practice, thinking that I must be lazy, but I’ve come to realize that it is a necessity.

If you get into a groove with your creative practice some very woo-woo stuff will start to happen, and it won’t be entirely clear how. A particular line or a story twist or a metaphor will appear on the page and you’ll be like, Holy crap, where did that come from? It will seem mystical, but it came from your practice.

I’m actually bumming myself out a little because my creative practice for writing fiction is very very rusty. It has been subsumed by the practice necessary for writing this kind of stuff, and for the kind of writing that will fill the book on writing in a world of AI that I’m hoping will sell to a publisher.

Fiction requires a good dose of daydreaming, of letting the subconscious bring things to the fore to see if they’re of interest. A nonfiction book is much more tied to active thinking, trying out ideas in my head as a kind of revving of the engines before getting down to the keyboard and putting them on the page.

For nonfiction I’m just reading reading reading to stoke the flames of my own ideas. For fiction, I’m spending more time feeling, experiencing the world, trying to keep my senses attuned to what’s going on around me so that can wind up on the page.

I think the fiction practice is still there somewhere, like a set of golf clubs in the garage you need to pull out from under a pile of other stuff and polish up before you hit the range to get your swing back. But I don’t have the time right now to do that polishing and practicing, maybe someday.

Another way we know that the algorithms are not creative is because a genuine creative practice is indefinitely sustainable. In fact, if sufficiently attended to, it becomes stronger over time, like a sourdough starter or something. My creative practice around the work I do now is well-honed, which is why I can write a 2500 word newsletter post in a few hours, and if I do this book, a solid 60,000 words will come together over four or five months on top of my other work.

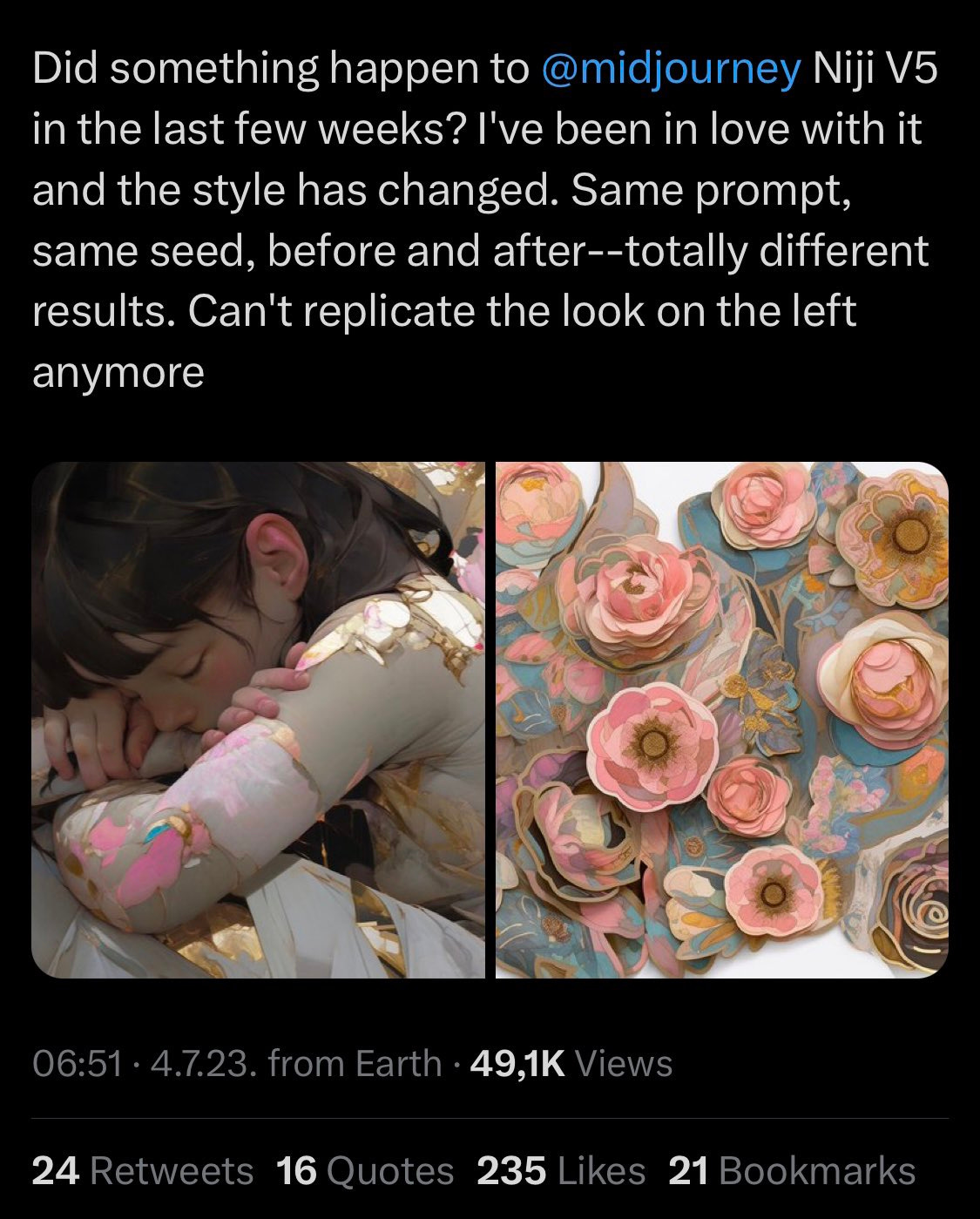

The AI models, on the other hand, are prone to collapse. This tweet from a MidJourney user got my attention:

The model no longer produces the desired image from a particular input. We do not know if this is true in this specific case, but it could be an example of what is known as “model collapse” where the AI degrades after feeding on too many images generated by its own model.

Researchers at Rice University established that without fresh training data, generative AI algorithms engaging in “autophagous loops” where they consume their own previously generated content will rapidly degrade in terms of their quality and diversity of output. They call this Model Autophagy Disorder or MAD as an analogy to MAD cow disease, which is caused by bovines eating feed contaminated with other cows.

I’m increasingly confident that AI isn’t going to replace us. It already seems clear that it needs us more than we need it.

The great thing about human creativity is that our own curiosity and the threat of boredom generally keep us from staying in one place. Let’s consider The Beatles again, who were experiencing life at hyper speed, and went from pleasant rock ditties like “Love Me Do” in 1962 to full bore psychedelia like “Tomorrow Never Knows” in 1966. If you’ve seen the Peter Jackson documentary Get Back, you’ll notice that even as the band was wrapping up their time together, when they were in a room with instruments in their hands they were just relentlessly creative. Not always focused, or obviously purposeful - a huge amount of the documentary is them farting around - but creative.

The Beatles may have had a limited lifespan, but all of its individual members continued to create for their entire lives, with Ringo and Paul still going even though they’re on the other side of 80.

I think there’s actually good reason to believe that building and living through a creative practice is correlated with longevity. Cormac McCarthy was 89 and still publishing. Mel Brooks is 97. Norman Lear is 100.

Joyce Carol Oates is 85 and just published another book, 48 Clues Into the Disappearance of My Sister. Margaret Atwood is 83 and still cranking them out. Toni Morrison passed away at 88.

I could go on and on.

There’s some tech near-billionaire who is dedicating his life lowering his epigenetic age, spending $2 million dollars a year on the array of supplements, creams, treatments, and tests that are designed to keep him young. Homie eats this every single day as one of this three meals:

He takes over 100 supplement pills a day and has a 60 minute skincare routine. The dude gets plasma infusions from blood taken from his own son.

Imagine how you could achieve the same results just by creating for a couple hours every day.

Links

At the Chicago Tribune this week I talk about how the experience of reading Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home overwhelmed my critical faculties in a great way.

The New York Times has “20 Great Queer Y.A. Books to Add to Your Reading List.”

Over at The Nation, Siddhartha Deb looks retrospectively at the 1980s novels of Don DeLillo as mapping of a country in inevitable decline.

It’s the New Yorker’s annual fiction issue, which has a couple of very choice pieces, including this very thoughtful essay from Parul Sehgal wondering what it means when everything is a narrative (“The Tyranny of the Tale”), and this Julian Lucas profile of one if the truly sui generis writers in American history, Samuel R. Delany.

And last, a McSweeney’s piece for the week. “Gentle Parenting in Classic Literature” by Jessie Gaynor.

Recommendations

All books linked throughout the newsletter go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and the Teacher Salary Project, which is advocating to establish a federal minimum salary for teachers of $60,000 per year. Affiliate income is $134.50 for the year.

1. Lords and Ladies by Terry Pratchett

2. Coming Up for Air by George Orwell

3. Truck De India: A Hitchhiker's Guide to Hindustan by Rajat Ubhaykar

4. Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri

5. The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying by Nina Riggs

Gowri - Bangalore, India

I will never get over the fact that there are people from all over the world who read this newsletter. Who’d have thunk it? Gowri looks like a good candidate for a classic from Jane Gardam, a man looking back on his life, at all that Old Filth.

Small announcement before a big announcement

I’m pleased to announce that I have a big announcement about the next phase of The Biblioracle Recommends coming your way tomorrow. I am pre-announcing that announcement so you are primed to read the announcement itself.

Consider this the trumpeters clearing out their spit valves just prior to playing the fanfare and look for that newsletter on Monday.

Take care, and stay cool all of you who are like me and are living somewhere very hot.

All best,

John

The Biblioracle

I don't entirely disagree, and over time, I imagine some kind of creative practice using the tool will emerge, but given that the tool itself is not stable, I wonder what that would or could even look like. For now, I see a lot of people who are truly reductionist by mistaking the product for the creative process.

Interesting that in all three of the AI Picasso's, the software assumed a male teacher.