So I decided to read Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus because it seemed like everyone else was.

This is not like me because I am self-declaredly famous for not reading certain books precisely because so many other people are reading them. I even wrote a whole column about how I was avoiding Amor Towles’s A Gentleman in Moscow for just this reason.

But I was won over by the story of a debut novelist in her 60’s finding such acclaim, plus that fact that it had been a New York Times notable book. Also, some folks from my book club said that the cover - which makes it look like something a Legally Blonde-era Reese Witherspoon would be starring in - was not indicative of the book as a whole. Everyone assured me it was a good book.

It’s also sold more than a million copies. I had to see what’s doing.

Everyone who told me it is a good book is correct. It is sharply written has a spiky main character, and is chock full of memorable scenes that add up to a propulsive story.

I put it down after reading 130 pages, about a third of the book, and will almost certainly not be finishing it.

I want to emphasize what I already said. Lessons in Chemistry is a good book. It is not schlocky, poorly-written, half-assed crap. It is an expertly done example of what it is trying to achieve. It’s just that as a reader, at this particular time - perhaps at any time - it’s not the kind of book that is going to sustain my attention.

But why? What’s going on here? Even though I am confident in my own judgment about my own taste, I could not put a finger on what was driving my discontent.

I knew that my lack of connection to Lessons in Chemistry is not because of latent snobbery. I read and enjoy lots of commercial fiction. Jack Reacher? Yes, please!

I tear through a handful of thrillers larded with implausible plot twists and serviceable (at best) prose every year. I read T.J. Newman’s Falling, in which an airline pilot must crash a plane in order to save his family who have been abducted by terrorists pretty much straight through in a day.

Lessons in Chemistry is more carefully written, with much deeper engagement with character than that book. It is set up to do more than drive you to keep turning the pages to see what crazy thing is going to happen next. By all rights, it should be a book I prefer over a (literal) airport thriller.

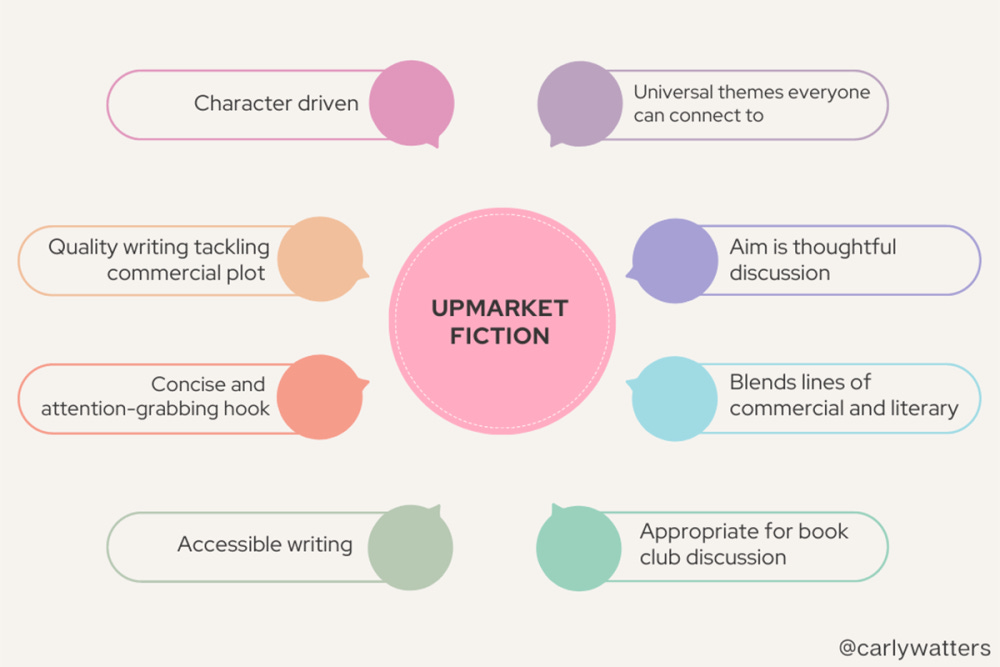

Thankfully, as I was working through my puzzlement, I read a post at Jane Friedman’s website titled What Is Upmarket Fiction?” by Carly Watters, a highly knowledgable literary agent, and it as though the clouds parted and the light of truth shone down. Suddenly I had a framework by which I could better understand my own response to Lessons in Chemistry.

I had heard the term “upmarket fiction,” but never attached any particular meaning or significance to it. I highly recommend reading the whole piece as it does a great job of breaking down the elements of different categories of fiction (commercial, literary, upmarket) and it may help you, like it’s helping me, better understand your own orientations around why you read what you read.

Perhaps the best place to start is in sharing Watters’ illustrations (used here with her permission) that show, graphically, the key traits of commercial and literary fiction.

Now, these discussions can sometimes get tricky as we can immediately think of exceptions to these categorizations that still fall under the “literary fiction” or “commercial fiction” label, but let’s stipulate that these distinctions are generally accurate and true. Commercial fiction is more concerned with pace and plot, with a kind of propulsive reading experience driven by action and event, while literary fiction is rooted in language, close attention to character, and moments of insight.

These are not meant as objective value judgements. They’re descriptors of traits, the same way oranges and bananas are both fruits, but one is round and orange and the other is long and yellow. You may prefer one over the other, but that preference is personal. There’s nothing objectively superior in terms of the individual reading experience about a book that aspires to “art.”

Upmarket fiction takes traits from literary and commercial fiction and blends them in ways that readers like. Upmarket is accessible and substantive. Unlike some literary fiction that seems to climb up its own keister, upmarket fiction is eventful/plotted. Stuff happens. In the part of Lessons in Chemistry I read, lots of stuff happens.

Unlike some commercial fiction where the characters are secondary to the mechanics of a caper or heist or military engagement, upmarket fiction gives you people that seem real that you like (this seems to be one of the most important traits) and become invested in for their own sakes. Indeed, Watters specifically calls upmarket fiction “character driven,” a label I might change to “character centered” because I think there’s a lot of upmarket fiction with plots as manipulative as commercial fiction, but the point is similar. Upmarket fiction wants you get invested in a specifically drawn character or characters in ways that commercial fiction doesn’t.

In upmarket fiction there is story tension around the ultimate resolution, but the final resolution is almost certainly going to be clear, unambiguous and satisfying.

In contrast, the conclusion of a work of literary fiction may be a head scratcher, steeped in ambiguity.

I have purposefully not listed a bunch of novels Watters (and I) consider upmarket fiction because I think it’s more fun to try to work through these things on one’s own, to try the ideas on for size and see if you can apply the theory to your own understanding of the world.

That restraint is about to end. Below the box urging you to subscribe I’ll start talking about specific upmarket fiction. You probably won’t be that surprised.

If you want to know what upmarket fiction is, you can look at the lists of books selected by Reese and Jenna and Good Morning America for their respective book clubs. As Watters says, “90% of their monthly book club choices are categorized as upmarket.”

I like a lot of the books on these lists. From Jenna’s list, Lily King’s Writer’s & Lovers, Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi, Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam, and Groundskeeping by Lee Cole are all books that I’ve read, liked, and recommended.

Reese’s selections include Infinite Country by Patricia Engel and Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid, books which wound up on my personal best of the year lists.

There’s also some books on these lists that I’ve sampled and abandoned like Lessons in Chemistry, along with other titles that I could not imagine being of interest to me in the first place.

I look at Carly Watters’ illustration of the traits of upmarket fiction and think, I like all of those things in a book, and yet there’s books that, as best I can see, embody all of those traits that I still don’t connect with.

As Watters’ points out, these books also rest on a continuum, with some upmarket fiction tilting toward the more commercial and others more literary. She identifies Liane Moriarty’s Nine Perfect Strangers as being the commercial end and Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner being on the literary end.

Lessons in Chemistry presumably would be in between those two books, closer to the median for upmarket fiction. Prior to reading Watters’ piece I would’ve guessed that my issue is that I simply prefer upmarket fiction that leans towards the literary side, but in fact, I’ve read two Liane Moriarty novels to completion experiencing the pleasures of solid commercial fiction, and would have to say that I prefer that experience over the more “pure” example of upmarket fiction.

Something is missing, for me, from upmarket fiction that sticks to the middle of the continuum.

Now is the time I step off the ledge and either make some sense that may resonate with others or nonsense that will make everyone think I’m full of 💩.

This is all thinking out loud from this place forward. I may change my mind about any of it, but there’s no better way to figure out what you do think than to share your thoughts with the world and see what the world has to say back to you.

I encourage everyone to disagree with me if they feel called to do so.

There are three areas where I think upmarket fiction is qualitatively different from both commercial fiction and literary fiction in ways that tend not to work for me as a reader.

Treatment of Character

In commercial fiction, the specifics of characters don’t matter. They are meat puppets being tossed around the mechanics of plot. They are one-dimensional.

In literary fiction, characters are complex and contradictory, possibly unlikeable, capable of change and surprise, and those complex contradictions determine the arc of events. The tension is often found in the ways the character is at war with themselves. They are three-dimensional.

In upmarket fiction, characters are interesting and more specifically drawn than in commercial fiction, but may not reach the complexities of literary fiction. The character is almost certainly someone we’re going to like and root for, and the story tension is driven not so much by internal strife, but by a hostile world bumping up against our character in a battle for supremacy.

As I was reading Lessons in Chemistry, I kept thinking of Amazon Prime series, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. Both the book and the show feature outspoken central characters challenging the ingrained sexist structures of their era and their chosen fields (chemistry and stand-up comedy). They are easy to root for even when you may not agree with their actions. Even when they are acting in ways that seem self-sabotaging in the short term, they are doing the correct and principled thing.

While I mostly enjoy watching Mrs. Maisel, I do not feel actual emotional involvement with the character of Midge Maisel because there is something about how the show is constructed that reminds me that she is just that, a character. I’m curious to know how the character’s life is going to turn out, but I am not interested in the inner life and experience of the world of the character because in the world of the show none of that really matters. It is not a source of interest.

I felt something similar reading Lessons in Chemistry, always aware that I was reading a construct, a “character” rather than a three-dimensional rendering of a person moving through the world.

As a reader, I seem to prefer my characters as either meat puppets or the fully-fleshed. That two-dimensional, in between place, tends to irk me as I feel manipulated by being asked to care about a construct, rather than invited deeply into the experience of someone else’s consciousness of the world.

In a recent Chicago Tribune column I wrote about being utterly absorbed by the experience of reading The Book of Goose by Yiyun Li. It was as though I’d been slipped in deep behind the lines of the consciousness of the novel’s narrator, Agnes. It was transfixing.

Elizabeth Zott of Lessons in Chemistry and Midge Maisel just aren’t built for that experience.

Flattering vs. challenging the reader’s sensibilities

I think one of the underlying traits of upmarket fiction is that the reader’s world view is generally affirmed by the storytelling in the novel. Given that the overwhelming audience for upmarket fiction is the same audience that does most of the book buying in America - middle-aged and older white women - that world view can become somewhat narrow, and for lack of a better word (though I think it’s a decent word), uncomplicated.

Consider a novel like The Help, a quintessential upmarket fiction book that is designed to assure the white readership that they are nothing like those horrible racists of the Jim Crow South. As my friend Kevin Guilfoile said of the novel, “the white people in The Help are, with only a couple exceptions, so one-dimensionally horrible that if you are a white person with anywhere from a center-right to liberal orientation, reading The Help will make you feel very, very good about yourself. If you are even moderately racist, in fact, The Help will probably make you feel good about the relative amount of racism you possess.”

Over time, audience attitudes change, so I actually think you wouldn’t see a novel like The Help published to quite the same acclaim today without greater critical pushback - at least I hope so.

But while there have been some changes in terms of how the dominant group views minority groups and the access minority groups have to tell their own stories - changes I would call progress, but others might not - we can look at the extreme popularity of a novel like American Dirt that traffics in racial tropes that are objected to by the group being portrayed, but which flatter white people and see that not all that much has changed.

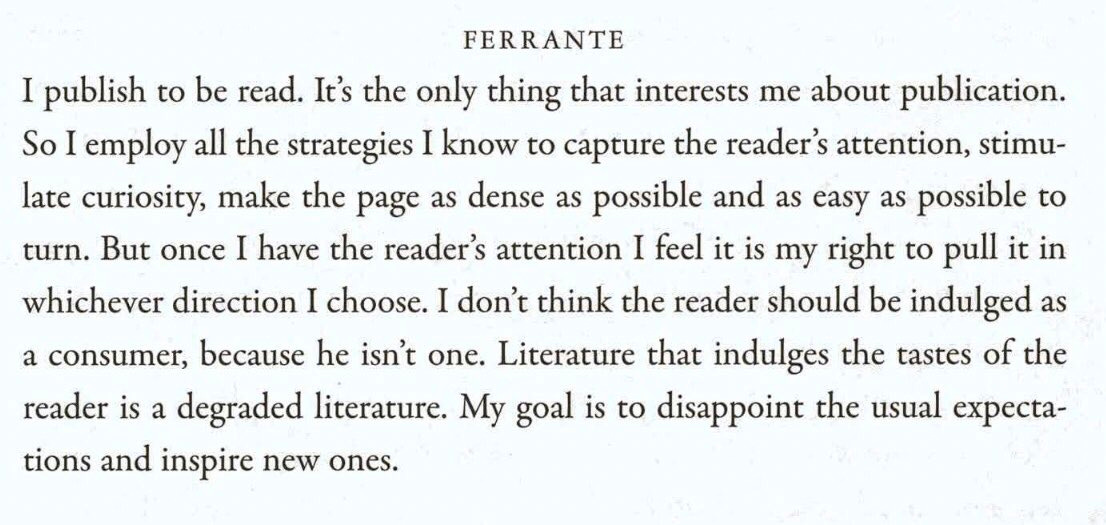

Another way of thinking about this was articulated by Elena Ferrante (My Brilliant Friend, et al.) in an interview with the Paris Review.

An upmarket book is unlikely to disappoint when it comes the expectations the novel sets for the audience. My favorite books are the ones that set and then challenge expectations and force me to grapple with that challenge.

Believing in feminism is the correct view for the audience of Lessons in Chemistry (or The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel), and it’s a view I share, but there is a novel that comes to mind that explores similar thematic territory in ways that challenges the reader’s own view of what is “correct” that comes to mind that I offer as a contrast: The Female Persuasion by Meg Wolitzer.

The Female Persuasion is about Greer Kadetsky, a young woman who is lit ablaze by Faith Frank, a leading figure of the women’s movement (think Gloria Steinem) who takes Faith under her wing. In the world view of the novel, we accept that striving for feminist ideals is a good thing, but the actions of the characters in the novel are also messy, contradictory, disappointing, and disillusioning. Faith Frank is a feminist icon, but also a human being with an ego and jealousies being buffeted by fame and weighed down by the responsibilities of leading a movement. Greer must deal with the realization that her hero sometimes has feet of clay, and that living by principle is sometimes not possible, maybe even not desirable.

It is a world view that is itself complex and contradictory, just like the characters who inhabit it. It makes for a considerably less comfortable, but for me a more enjoyable/deeper reading experience. Perhaps another way of thinking about this is that a mainstream upmarket novel will deal with important subjects, but do so in such a way where the sides are clear.

I prefer an approach where there are no sides because instead we’re going progressively deeper.

Either that, or I want the stakes to be so black and white that all I care about is seeing how the hero is going to wiggle out of a jam using some clever strategy that no one else could have considered.

I should note that while Meg Wolitzer is a highly accomplished, best selling novelist, her books sell at a magnitude many times lower than Lessons in Chemistry.

The pleasures of open endings

I think one of the most important distinctions between upmarket and literary fiction is the ambiguous ending.

Personally, I love a book that finishes without concluding, that makes you pause and consider what the ending means and gives the reader that sensation that this is a life that is going to continue in interesting ways, even though we will not be privy to seeing it unfold.

Most readers, however, like closure. I have not made a scientific study of it, but doing a bit of a spot check on the books in the Books with Jenna club that I’m familiar with, there appears to be a strong correlation between books that offer closure and higher sales (as measured by the number of Amazon reviews).

This is not surprising. Research from Daniel Kahneman (some of which is discussed in his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow) has shown that we are quite literally wired to privilege how we feel about the end of something as a proxy for the entire experience.

If we have a week-long vacation where the first three days are marred by travel problems or lost luggage or bad weather, but the end is glorious, we will think of that trip more fondly than one where something bad happened at the end.

Just about everyone has had the experience of feeling that a story has been “ruined” by a “bad” ending, which can seem silly given that you’ve possibly spent many hours of pleasure reading a book and only a minute or two experiencing that disappointment.

That said, a flight is judged not on the smoothness of the journey, but whether or not the pilot lands the plane. When it comes to narrative, people really really really want the author to land the plane, but of course landing the plane is not easy.

An open or ambiguous ending is not necessarily a bad ending, but many people simply feel dissatisfied if they are not provided that feeling of closure. Perhaps the best example of public discontent over an open ending is the concluding episode of The Sopranos, which I thought was awesome once I figured out what they’d done, but others consider it one of the worst endings to a show of all time.

Of course, whether or not you will accept an ending without closure hugely depends on what happens prior to the end. The TV show Lost has another ending widely considered to be terrible - for good reason, it is terrible - but I would argue the reason it’s not good is because too much weight was put on the question about what the hell was going on with that plane and that island? The end of the show attempts to give the audiences the closure they desire, but lots of use were left asking, That? Seriously?!?

Purely speculating now, but I would guess if there’s any single divide that separates the median upmarket book from the literary end of the scale, it’s how they deal with the end.

Even after almost fifty years of reading, having the chance to work through my response to Lessons in Chemistry helps me feel more in touch with my own tastes. I hope that seeing me wrestle with my response helps you be a little more in touch with your own.

Links

At the Chicago Tribune this week I share my excitement about the new publishing imprint of Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson and encourage publishers to approach a few more celebrities to establish their imprints.

The Tournament of Books concluded this past week. The final matchup pitted Babel vs. The Book of Goose.

As the son of a bookseller, I can say that this is a very fun remembrance by Charlie Becker, the son of a bookseller and their annual pilgrimage to the Brandeis Book Sale in suburban Chicago.

Ireland has started experimenting by paying 2000 artists the equivalent of around $18,000 a year with no strings attached to help give them time to produce more art.

The New York Times has one of those fun little book trivia things on books that inspired popular songs. This is a gift link so anyone should be able to access it. (I only scored 3 of 5 on this one.)

Over at LitHub, Janet Manley ranks literary baby names from “least to most cringey.”

At McSweeney’s, Jonathan Allen does the work of providing, “Every Page of Goodnight Moon, Ranked.”

At the Yale Review Garth Greenwell has a long read exploring his continued love of Philip Roth’s work that I’ve only dipped into because it’s going to require a period of extended concentration to truly appreciate.

Recommendations

I used all the open requests in the column I drafted this week, so there’s nothing N sitting in the queue that I can see. If you sent in a request that I missed, please resend. The link below tells you how to get a custom book recommendation.

Phew. Took some effort to land the plane of this post this week since so much of my thinking hadn’t been done before I put fingers to keyboard.

Such is the way sometimes.

Have a great start to your Aprils, all,

John

The Biblioracle

Demonstrating the things we already believe, or want to believe

Meg Wolitzer

Now I feel really bad that we encouraged you to read Lessons in Chemistry at book club… I think it might surprise you if you finished it, but who knows. I appreciate the discussion on upmarket fiction. Historically, I don’t read much contemporary fiction but I’ve been doing it more (blame The Village Bookseller) and this framework is helpful to process how I feel about these books (many of which I’ve loved, but also found forgettable). Interesting because I just finished The Violin Conspiracy and haaaaated it, in great part because of the reasons you didn’t like Lessons. And based on reviews, I expected it to lean more literary, but instead I found it to be a barely-upmarket example if there ever was one (and a tediously written one at that).

Oh, and A Gentleman in Moscow. Do it. It might meet many of the criteria for upmarket fiction, but the writing… oh, John, the writing.

Agree. For me, upmarket fiction is a bit irksome, a bit wanna-be. Often well written, technically, sometimes they seen to have been run past too many focus groups and taken on all feedback to appeal to a generic market. They are usually instantly forgettable, no flavour lingers.