(This is a mini epic that may not display in its entirety in email clients, which is a shame, because this one’s a corker. To make sure you read the entire text, click through for the version on the web.)

I sincerely thought I was done writing about former New York Times Book Review editor Pamela Paul after a previous newsletter in which I connected the dots (in still another newsletter) between one of her columns and what seemed to be a curious pairing of book and reviewer that stacked the deck in favor of a positive reception for a book sympathetic to the (initially) U.K. phenomenon of TERFs (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists).

But then she had to go and re-litigate the three year old controversy about the publishing and promotion of American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins, and well…I had my Michael Corleone moment in Godfather 3.

For those who don’t recall, American Dirt was published to great fanfare, receiving a seven-figure advance, rapturous blurbs, and a slot in Oprah’s recently reconstituted book club.

It was touted as not just a page-turning, emotional thriller, but also an important social novel along the lines of John Steinbeck, the kind of novel that could make a difference in the world. It was blurbed, rapturously (because that is the only kind of blurb) by the likes of Stephen King, Ann Patchett, Don Winslow and Julia Alvarez.

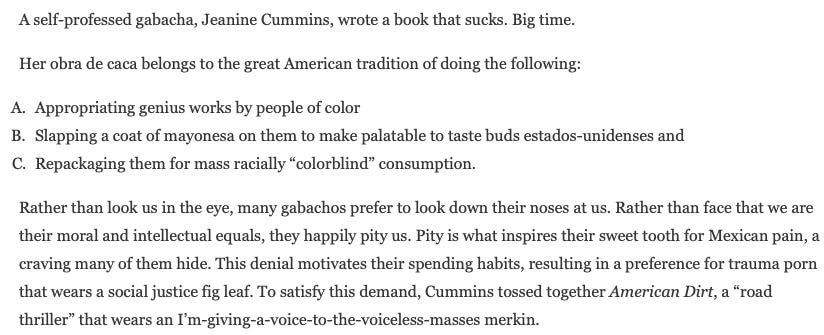

The controversy was initially launched by the writer, Myriam Gurba (author of the memoir, Mean) who was commissioned to write a review of American Dirt by Ms. Magagzine, but had her review spiked because it was too negative. Gurba subsequently published the review and additional commentary at Tropics of Meta, and a broader discussion about the problems cultural appropriation resulted.

It’s important to note, however, that Paul and others (as we’ll see) reverse the causation of Gurba’s actual argument. Gurba does not argue that because Cummins is not Mexican she has no right to publish the book. No, she’s arguing, fundamentally that American Dirt is a bad book, and that because it is a bad book, the publisher has no business promoting it though a lens of authenticity (thanks to the author’s identity).

Gurba is calling out what she sees as a phony attempt by big publishing to capitalize on a hot button issue, using a surface-level commitment to social justice to inflate the importance of the book.

Paul, on the other hand wants readers to believe that we are in the midst of a crisis of progressive overreach that seeks to silence anyone who doesn’t toe the ideological line or have the proper identity bona fides.

But this is nowhere close to what Gurba was arguing, and as contemporaneous reporting by Lila Shapiro reveals, the book’s publisher was only too happy to tout Cummins’ identity as half Puerto Rican, and fluent in Spanish, with an undocumented husband (who is Irish, not hispanic it turns out) as credentials that bolster the authenticity and social value of the novel.

Look, anyone who enjoyed reading American Dirt will not hear an ounce of guff from me. I’m certain it is a page-turner and emotional, and satisfies many readers. Books don’t need to be important to be satisfying reads. You’ll pry my Reacher novels out of my cold dead hands. American Dirt’s millions of copies sold and four and a half star review average suggest there are many happy readers.

But if you try to tell me that American Dirt is an “important” novel, that it is incisive regarding the migrant experience or what’s going on at the American border with Mexico, we’re going to have an argument on our hands, and that’s where the controversy around this book lies.

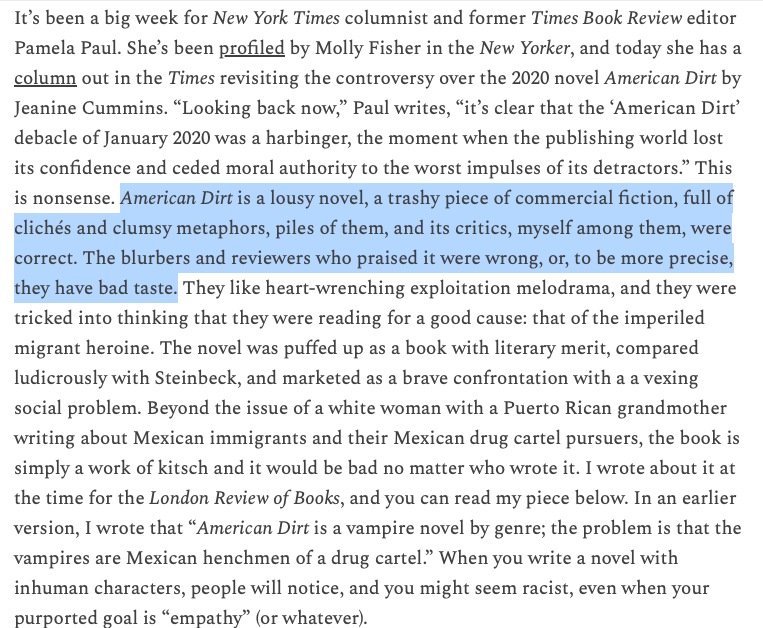

At his newsletter

, Christian Lorentzen punctures the pretentions around the novel, by both noting some of the nonsense that Paul is peddling, and sharing his review of the book from its time of publication.While you won't get an argument from me if you say you enjoyed reading American Dirt, you will get one from Lorentzen, which is why he is an excellent book critic, and why I don’t write book criticism:

I was considering doing a paragraph by paragraph takedown of Paul’s piece, but thankfully,

did something better at his newsletter, penning a hypothetical editor’s note to Pamela Paul that is simultaneously utterly fair, and completely devastating in the way it scrutinizes and punctures Paul’s logic and evidence.I want to be clear that independent of the specific opinions Paul holds that I disagree with, the reason I’m so irritated by the piece is because it commits what I think is the cardinal sin for any writer, it deliberately treats the audience like they’re dumb, and demands agreement, rather than engagement.

I’ve got a lot of limitations as a writer, but one thing you won’t find me doing is failing to be transparent with readers. Paul practices deliberate opacity.

This absolute failure of Paul to be forthright with her audience is well-illustrated by Max Read when he points out that while Paul’s column is positioned as though Paul was some kind of bystander to the whole episode, in fact, she had a central, insider seat as the editor of the Times Book Review who commissioned a review of American Dirt by Lauren Groff, a largely positive review, that was in stark contrast to a review by Parul Sehgal in the daily paper that panned the book.

This is Read putting his finger on the point, hypothetically addressing Paul in his editor’s note:

There are few people who are in a better position to shed genuine light on the inner workings of the publishing system than Pamela Paul, and she utterly refuses to do so in order to instead write a piece that flatters the sensibilities of the people who nod their heads when someone says “wokeism is a religion,” and then draw false equivalencies between progressive criticism of speech and actual book bans. These people appear to be legion in the reader comments on Paul’s column which is simultaneously depressing, and also a good illustration of how Paul is writing from a position of power, somehow managing to spin the majority as an aggrieved population.

Even if you do nod along when people say things like “wokeism is a religion” you should be chagrined that a writer as dishonest and lousy as Paul is carrying your torch.

Apparently, I’ve got more to say. I’m actually a little hesitant to go where I think this is about to go, but I think that hesitation is illustrative of the underlying attitudes that led to a book as limited in its achievements as American Dirt getting rapturous blurbs and rave reviews from people who are absolutely capable of detecting Cummins’ tortured prose and discerning the difference between a satisfying melodramatic thriller and a novel of lasting Steinbeckian importance.

Even as someone who knows he’s well past the possibility that a commercial publisher will take on one of my novels - should I ever finish writing another - I hesitate being too forthright about what’s going on here, lest I offend someone who has the power to make something like that happen.

This is the kind of power that Pamela Paul wielded at the Times, though Paul denied this in a profile of her by Molly Fischer, published this week at New Yorker:

Fischer’s profile is both scrupulously fair, and a devastating exposure of the way Paul declares those she sides with as fearless, while labeling the criticism of others as out-of-bounds. In reality, Paul weaponizes a politics of grievance on behalf of the status quo in order to attempt to quash the voices of those without her power and influence.

It’s gross.

This is actually a good illustration of why you should not put any stock in book blurbs whatsoever, and book reviewers who are not novelists and who aren’t dependent on being a good citizen of the publishing industry are so important. Christian Lorentzen punctured the book. So did Parul Sehgal in her Times review, declaring:

Sehgal discusses the “cultural appropriation” elephant in the room, but also ultimately comes down in the same place as Myriam Gurba. It’s not that an outsider wrote the story that’s the problem, it’s that an outsider wrote the story poorly. As Sehgal puts it, “The real failures of the book, however, have little to do with the writer’s identity and everything to do with her abilities as a novelist.”

One of the worst parts of Paul’s column is her attempt to cast legitimate and supportable criticism as out of bounds, the equivalent of those who would like to ban books. The even worser part is who Pamela Paul gets to ride shotgun for her on this contention.

Ann Patchett is a justifiably loved and celebrated figure in the world of books, but this false equivalence is utterly risible, and is the kind of attitude that helps the actual book banners, like Ron DeSantis in Florida, who this week has classroom teachers literally stripping their shelves bare in order to comply with newly passed restrictions.

Look…I’m sure that the controversy was very upsetting for Jeanine Cummins, but the idea that the criticism of the book by Myriam Gurba, Parul Sehgal, and others, or the public backlash over a themed reception for American Dirt which incorporated centerpieces that featured “walls” covered in razor wire, was somehow unfair is special pleading for the 1%.

No serious person was declaring that a white person cannot write about Mexican people or the border crisis, or that men cannot write about women, or whatever. I mean, maybe some people are saying this, but don’t listen to them, they’re wrong. That Paul frames the controversy as being about these issues is another example of her treating her audience like they’re dumb.

What people were saying at the time, including me in a Tribune column, is that if you do decide to write across identities, you should do it well, or you will risk justified criticism.

For too long the people who keep the gates of what gets talked about and how it gets talked about have been too sheltered, too cautious, too naive about these things.

The criticism of American Dirt is progress that is long overdue, and which has been slowed by the lack of awareness and sheltered perspective of people like Pamela Paul.

And also me.

In a number of ways, the positive reception of American Dirt reminds me of the positive reception of The Help, a novel from 2009 about Black domestic servants in Mississippi during the Jim Crow era that also spawned a rather popular film. Both books deal with difficult issues around race by making the treatments safe for the white majority to embrace without feeling overly judged. American Dirt does it by couching the story of migrants in a thriller of a mom on the run from the drug cartels.

The Help does it by centering the story of a well-meaning white savior character who tells the stories of the Black help, bringing attention to their treatment, and even sharing the proceeds of the stories with them.

In what is perhaps not a coincidence, the same editor, Amy Einhorn, (then at Flatiron, now publisher of Henry Holt), acquired both American Dirt and The Help. Einhorn might be responsible for editing more mainstream bestsellers than anyone ever. She has an unerring radar for what the main constituency of the book buying public - white women - are interested in. This is an observation, not a criticism. If Amy Einhorn liked one of my manuscripts, I would be over the moon.

Thanks to the Tournament of Books I have a contemporaneous account of my public commentary on The Help, as it was a competitor in the 2010 tournament. My co-color commentator Kevin Guilfoile and I offered some somewhat tepid questions about what a narrative like The Help says to the world. This is about as strong as my questioning got:

Kevin followed my thread:

Here’s a couple of (at the time) forty-something white guys who seem to get that there could be something off about the novel, but in the end, who cares, right? The better word(s) I was looking for was not “wrong,” but “condescending and racist.”

Thinking about this in hindsight, I asked Kevin how he feels about this today, and he replied, “I think at the time I saw The Help as being mostly well-intentioned, but oblivious. I think the last decade has proven that to be completely fucking wrong. There is a direct line from the comforting white narrative of The Help to Ron DeSantis saying you can’t teach any history that gives white kids a sad.”

You won’t hear from me or Kevin or anyone that The Help should be banned, or shouldn’t have been published in the first place, or that enjoying the book makes you a bad person, and even if someone did say that, so what? The same goes for American Dirt. If people want to read those books or any others, I’m not going to stop you, but I’m not going to shut up just so everyone can do so in comfort.

But what galls about Pamela Paul’s piece and Ann Patchett’s quote is the notion that we’re all supposed to continue to be silent about these things that are as obvious as, well…dirt.

Paul ends the column with an attempt to shame those of us who had the temerity to criticize Cummins.

The criticism of the book and much of its marketing was precisely about the failure of empathy, and the sense that a marginalized community was being exploited for profit, an outcome that actually happened.

Patchett’s breaking heart over the hurt that Cummins felt over the criticism is a human response to a friend’s distress that has nothing to do with the broader issues. She is equating what she calls “shaming” (which is actually criticism) with banning books.

Seriously?

Also, I happen to have first-hand experience that Ann Patchett is, or at least at one time was not above judging an author for writing something bad. I know it because she did it to me.

I really wasn’t going to tell this part in the newsletter, but it’s a story I’ve told privately a few times over the years, and as someone who just up the page said that the most important responsibility for a writer is to be transparent with their audience, I figure I have to put this in.

Let me say that from the outset that I don't consciously bear any grudge towards Ann Patchett, have read and enjoyed quite a few of her books in the many years since this incident, and have recommended them often. I’m certain she’s a good and caring person, and her bookstore, Nashville’s Parnassus Books, is a treasure.

But also, she said something to me about my story, and how I approached writing in general that made me want to quit writing altogether, and did lead me to hang things up for about six months, months which were among the lowest of my life. I’m certain she wouldn’t remember this, as it would be utterly unremarkable except to the still young person who desperately wanted to know if he had the stuff to make a life as a writer and had invested far too much in the opinion of someone who was already established in that world.

This was during my last semester of graduate school when Ann Patchett had been invited to give a reading and do one-on-one conferences with the handful of graduating students. As I recall, she read a passage from a forthcoming novel, The Magician’s Assistant. For my conference, I’d submitted a story titled “Sandy Koufax’s Head” which was told from the point of view of a guy who runs a Putt-Putt golf franchise that’s located across the street from a much more popular miniature golf spot which is owned by an old Holocaust survivor named Schwartz.

There is a difference between Putt Putt and mini-golf. Putt-Putt is largely standardized, with very little chance involved in the outcome, while mini-golf has windmills and roller coasters and the like. My narrator has had a bit of a rough life and his Putt-Putt golf course has put him on a better path, but Schwartz’s mini-golf, which is filled with holes dedicated to famous jewish people throughout history (including Sandy Koufax) is, understandably, more popular in the town of Skokie, Illinois where the story is set.

The narrator commits an act of vandalism against the mini-golf place, trying to put it temporarily out of commission to boost his own bottom line, leading to unforeseen complications and a mix of farcical and tragic events. It’s the kind of mix of tones that I was endlessly experimenting with at the time to little success, but which I nonetheless have persisted in trying to pull off for the entirety of my career.

Here’s the important thing to know. The story is not good. It is worse than not good. It is bad. It displays some inventiveness and wit and has some decent writing, but it is not at all successful, and because of the swing I took at mixing the comic and the tragic in the context of neo-Nazi violence and the Holocaust, the result is pretty disastrous. It is a fair response to read the story, and upon reading it to turn to the author and say, “You shouldn’t have done that.”

I have not looked at the story in many years, but this is the thought I had about it the last time I did look at it.

Ann Patchett, being an accomplished professional, told me this obvious truth, but she also went a step further and explained why what I was trying to do in general - mixing the silly comedy and the tragedy - was an overarching bad idea. In her view, I was misguided about the enterprise at a core level.

As I experienced it, there was very little gesture towards empathy in her response, no attempt to hash out what I might’ve been trying - and failing - to achieve. What I took away from the conference was that, essentially, I’d been wasting my time doing what I’d been doing over the course of three years.

The reason this criticism landed with such force was because I’d already been having those thoughts on my own, having failed to have much success writing something satisfying while I was in school. Patchett did not intend to shame me, and yet leaving the conference held on my professor’s back porch, I felt ashamed.

Ann Patchett did nothing wrong - she was asked to read student stories and provide her honest feedback - but that conference was the reason I tried my hardest to stop writing in the months after I graduated.

(I filled a chunk of those months reading Infinite Jest instead.)

Eventually, the desire to write returned, spurred by seeing something odd on my walk to the train in downtown Chicago on my way home from work, a woman with an umbrella who I thought literally disappeared into the fog from no more than six feet in front of me. That incident, combined with some other stuff, became a story called “The Circus Elephants Look Sad Because They Are,” the first story I would ever publish, in the third issue of McSweeney’s Quarterly.

Paul and Patchett ask for empathy on behalf of Cummins, or other writers whose books are not getting published because of fear of left censoriousness, but let’s be real about this. Following Paul’s column, numerous hispanic writers took to Twitter to describe the consistent dismissal and marginalization they’d experienced at the hands of a publishing power structure that remains overwhelmingly white, and publishes a disproportionately small share of minority authors.

I do have empathy for Cummins, not because she’s not asked to blurb any books (Paul’s evidence of harm) - lots of writers would consider that a blessing - but because I imagine that once a publisher pays seven-figures for your book, and Oprah anoints you, things get really exciting and a little scary. Add in that people are starting to talk about your book in ways that make it sound like it’s not just going to be a strong seller, but is also “important,” and that would be a heady cocktail to try to drink down and stay balanced.

So when the criticism comes it feels like the world is caving in.

But the world did not cave in. The book was a bestseller. Millions of copies sold.

Ann Patchett had no responsibility for my feelings and my fragile psyche at time she read my short story. It was up to me to absorb the slings and arrows of the world and decide if I wanted to keep doing this.

The empathy of book critics should extend no further than believing the author wrote the best book possible. The criticism seems harsh because the book did not live up to its purported promise. That’s not the critic’s problem.

Pamela Paul wants to maintain a world where people like her get to remain forever comfortable to the point where their discomfort is the equivalent of actual tangible harm like censorship.

Ridiculous.

Links

As of publication time for this newsletter, my Chicago Tribune column this week is not yet live on the internet, but it will be at the top of this list and concerns the strike of HarperCollins staffers, which is about to enter its fourth month.

The Chicago Review of Books has the “most anticipated Chicago books of 2023.

Over at Lincoln Michel has a very intersting conversation with Martin Riker about writing and novels on the occasion of the publication of Riker's novel, The Guest Lecture, which sounds fantastic. Twenty-five or twenty-six years ago, I went out to dinner with Riker, Dave Eggers, David Foster-Wallace and a few others near the Illinois State University campus after I’d accompanied Eggers there for a reading. I was a little starstruck by DFW, but it’s talking with Riker that I remember the most, thinking how curious and smart he seemed. For years he’s worked in independent non-profit publishing, including the indispensable, Dalkey Archive Press, and as co-founder of Dorothy, a publishing project, with his wife Danielle. I’m thrilled that he’s publishing his first novel and can’t wait to read it.

In the early days of this newsletter, I used to share a four-legged “reading companion of the week” in honor of the creatures that keep us company. At her newsletter this week, Jami Attenberg pens a tribute to her best little writing companion, a puggle named Sid, who sadly passed away this week.

Here’s an article about a weird feud between William S. Burroughs and Truman Capote that I never knew existed.

Quentin Tarantino has a much healthier understanding of the issues discussed in today’s newsletter than Pamela Paul.

Recommendations

I used up all my pending recommendations in the column copy I wrote for next week’s newspaper, so if you’re looking for a quick turnaround, now’s your chance!

I know I promised another installment of “A Book I Wish More People Knew About” this past week, but other work swallowed the time. This coming week it’ll be up, I swear. (This is why I need a part-time editor to help.)

Enjoy your weeks, and give those reading (and writing) companions an extra hug and scritch. These are my guys one time when they were making it very hard to read.

John

The Biblioracle

"You’ll pry my Reacher novels out of my cold dead hands." Mine too.

As a European (German) I didnt really know about the "controversy", but it seems I dont need to - it seems to be a usual "famous person says something and then equate criticsm with censorship - but onl criticism of them, not of the other side". This has plagued many fields.

And yet I absolutly liked your writeup for its nuances and arguments. Thats how its done.