Early in the week, I was pretty sure I was going to put a little outrage into the world via this newsletter.

My motives were various:

I felt genuinely outraged.

Expressing my outrage on Twitter resulted in significantly higher than normal engagement with, adding a number of new followers to my tally.

Stoking ire at a particular person or group that other people also feel ire towards is probably the most straightforward and quickest way to build up an audience here on Substack, something I should be actively trying to do.

But after seeing some of the additional outrage I stoked with my outrage, and gaining some distance from my initial outrage, I decided rather than being outraged on the page, I would instead write about outrage and see what I might figure out for myself.

The Source of my Outrage

My initial ire was raised by an article by Brown University economist Emily Oster in The Atlantic declaring the need for a “pandemic amnesty” about decisions made during the height of the pandemic when information and knowledge was limited. In general, this sounds good and right to me. In order to move forward it does not help to endlessly litigate parts of the past you can do nothing about. I was irked, however, by Oster’s framing of those who had been (and continue to be) critical of her insistence that it was safe to reopen all schools to in-person learning as early as Fall 2020 as one of the groups that needs to be forgiven, probably because this is a group I belong to.

I was additionally irked because Oster confidently continues to insist greater declines in student scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) exam were caused by greater durations of remote instruction. This is obviously a reasonable hypothesis, but there is no convincing evidence that it is true, despite much effort expended by Oster and others to demonstrate it. The NAEP is not constructed or administered in a way that allows for any such conclusions to be made. The available evidence suggests that there are simply too many different factors that disrupted student learning to pin specific or particular declines in scores on a single variable, like longer remote schooling.

As someone invested in education, I am troubled by simple explanations for complex phenomena. Suggesting that all that matters is in-person school absolves us from learning the deeper lessons available about pedagogy that have been revealed by the pandemic. As I wrote earlier this week at Inside Higher Ed, I believe that looking at the specifics of what learning has been lost could be useful in adjusting how and what we teach.

But if the conclusion we’re meant to draw - the conclusion that follows from Oster’s hypothesis - is simply that students needed to be in class, we’re never going to have those discussions.

So, I tweeted about my discontent, linking to data that I believe challenges Oster’s conclusions, and a little storm of outrage at Oster started to build as replies and quote tweets to my original. Meanwhile, there was also a portion of counter outrage aimed at both Oster and people like me for advocating for precautions like masking, which were akin to child abuse and blah blah blah blah.

It got pretty depressing pretty fast, and became even worse as people tweeted additional information about Oster into my replies.

While I was familiar with Oster’s best selling books on pregnancy and parenting, I was not aware of her origin story. She first gained public prominence for a paper challenging Nobel winning economist Amartya Sen’s theory from 1990 that there were 100 million fewer women in Asia due to anti-female discrimination.

Oster thought she had debunked this theory by looking at the prevalence of Hepatitis-B in Asian women. There is some evidence that women infected with Hepatitis-B are more likely to give birth to boys. Oster did some data analysis stuff to show that this could account for up to three-quarters of Sen’s missing women.

Prior to its peer review and publication in an academic journal, Oster’s theory was hyped by none other than Steven Levitt of Freakonomics fame at Slate establishing Oster as a young up-and-comer with a novel theory challenging a Nobel Prize winner.

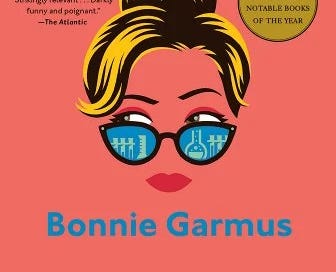

(Regular readers know my stance on Freakonomics being the “most harmful airport book of all-time.” Cue increasing outrage.)

As it turns out, Oster was wrong. Her data was shoddy, the analysis didn’t hold up and she ultimately withdrew (to her credit) her own claims.

But a star was born. Her next moment of public attention was a TED Talk in which she essentially argues that the people of Africa shouldn’t be getting anti-retroviral AIDS drugs because they’re too poor and are going to die of something else anyway. While there is a way to spin this as a call to also help the portions of the continent that remain impoverished, if you watch the video, the presentation is more along the lines of suggesting that western countries shouldn’t waste their money on a lost cause.

Oster is championed as someone who “uses data to challenge conventional wisdom,” but like the Freakonomics guys, she does so in a way that is often misleading or overbroad, and/or to my way of thinking, morally wrong.

Seeing these bits accrue to my Twitter thread, and the Twitter notifications of other people’s outrage pile up, I began thinking about a newsletter post that would give this Emily Oster a piece of my mind.

But then I noticed that some of my fellow outraged were convinced that Oster actively wished the vulnerable and immunocompromised to die. This felt excessive. In the article, Oster says she has been called a “génocidaire,” which given the necessity of intent in order for something to be classified as a genocide, is truly extreme.

Emily Oster has a husband and three children. Because she has parents famous enough a economists themselves to have their own Wikipedia pages, I learned that her mother passed away just a few months ago. I’m certain she is grieving this loss.

While I think she knows precisely nothing about pedagogy and does real harm when she applies her method to educational practices , I do not think that Emily Oster actively wishes for more people to die. I’m sure, like me, she wants students to learn important stuff in school. I’m sure she loves her children and husband. I’m certain she believes - as I believe about myself - that the ideas she puts into the world are a net benefit for society. Sure, she has benefitted mightily from those ideas, but those benefits are not her motive.

Oster’s parents were prominent academic economists. Her husband is an economist who was chosen as a prestigious MacArthur Fellow. I think she is an example of what Elizabeth Popp Berman calls “the economic style of thinking” on steroids, and that people in power in this country lap up this kind of thinking, even though it is so often wrong, is a problem that extends well beyond Emily Oster.

Part of the problem may be the sheer prevalence of outrage (particularly online) itself, and who and what seems to benefit from a culture of outrage.

“Outrage Is Winning”

Writing at the New York Times this week, Tressie McMillan Cottom breaks down the significance of Trevor Noah’s announcement that he’s leaving The Daily Show, as part of a larger shift around late night comedy television.

Late night post Johnny Carson, (who people erroneously describe as apolitical, but in reality was a status quo Republican1), has been an increasingly liberal space, as first seen with Jon Stewart's The Daily Show and its cousin, The Colbert Report, but in the Trump era, Colbert (in his CBS show), Jimmy Kimmel, Seth Meyers, and even Jimmy Fallon (to a lesser extent), appear partisan because of their opposition to the former president. As Cottom put it:

The smart aleck attacks aimed at Trump served as a kind of resistance, as liberal audiences upset at what was going on found someone who not only agreed with them, but used humor to point out the obvious hypocrisies.

But as Cottom observes, there is a fundamental asymmetry in how these forces play out in the culture: “Liberals may be drawn to ironic humor like satire because it reflects their antagonism toward the status quo. But outrage plays better to the political psychology of conservatives. As outrage has become a more viable media model than satire, it has gotten harder to sell liberal politics.”

We should have known we were doomed the moment Melissa McCarthy took to the Saturday Night Live stage to lampoon first Trump press secretary Sean Spicer’s bizarro press conference insisting - against all available evidence - that the crowds for the Trump inaugural were the biggest ever.

The entire conceit of the bit is McCarthy, as Spicer, performing over-the-top outrage because of the unfair treatment he has received from the press challenging his obvious lies. The sketch unfolds with cast members - and guest host Kristen Stewart - asking standard questions that McCarthy/Spicer ridicules as “stupid.” The members of the press are cowed and befuddled in the face of Spicer’s rage. The “joke” for liberals is what a buffoon this guy is, and I suppose the theory is that being lampooned on Saturday Night Live, may lead to a change in behavior because who wants to get laughed at?

If I believed this at the time, and maybe I did, it’s a dumb theory. Focused outrage will defeat smart aleck mockery any day of the week. Later in the sketch, Kate McKinnon appears as Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, and after being asked an education-related question, McKinnon’s eyes go wide, expressing DeVos’s total ignorance of what is being discussed before answering:

I don’t know anything about school, but I do think there should be a school…probably Jesus school. And I do think it should have walls and roof and gun for potential grizzly.2

At this point, McCarthy/Spicer shoves DeVos away from the podium, suggesting that she’s an embarrassment, but six-plus years beyond that moment, the DeVos vision for education is on the cusp of realization.

The recent Supreme Court decision in Carson v. Makin paved the way for universal vouchers, which would allow public money to be used to fund “Jesus school.”

Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin won office on the back of an entirely manufactured panic about teaching Critical Race Theory in schools. The “hotline” Youngkin established was quietly shut down in September after receiving virtually no complaints about CRT, but instead becoming an outlet for general parental discontent.

In the New Yorker this week, Paige Williams covers the right-wing Moms for Liberty group, which has wreaked havoc in school districts across the land, challenging curriculum and educators on bogus complaints, often brought by people who have no children in the actual systems where the complaints are brought.

It takes only a moment to spin up a storm of outrage, but it make take months to tamp it down and the people on the front lines become exhausted, teachers simply leave, rather than defend themselves. School board members that have to defend themselves against bad faith attacks decide that public service is not worth the harassment, leaving the field open for the outraged to rampage.

Using ironic humor as a defense has no chance against people determined to be outraged even in the face of a countervailing truth.

The Daily Show’s Jordan Klepper is a master of in-person, real-time puncturing of MAGA hypocrisy. In a recent visit to Michigan to talk to Republican voters in the midterms, he has this exchange with a woman dressed in pro-Trump gear who is “Not a (current governor and Democrat Gretchen) Whitmer fan.”

Klepper: Her [Whitmer’s] numbers look pretty good right now.

Self-declared Trump Fan: That’s baloney, I don’t believe those polls.

Klepper: You don’t trust polls.

SDTF: If they’re done by Republicans, yeah I trust the polls.

Klepper: If they’re telling you what you want to hear, then you trust the polls.

SDTF: (Laughs.)

Klepper: It’s important for polls to not reflect reality, but to reflect your reality.

SDTF: Exactly.

In an earlier post, I wrote about my belief that when something is funny, it’s because it is true,” that the laughter itself is a signal of recognition of being confronted by something we deep down recognize as accurate and true. The woman Klepper interviews laughs when he lands the joke at her expense, but the laughter has no literally no impact.

Even when directly confronted with her own hypocrisy, and some part of her psyche recognizing her hypocrisy in the form of that laugh, she will not change her view.

I cannot imagine a better illustration of the impotency of irony and humor in the face of outrage.

Unfortunately, this is a lesson I should’ve learned long ago.

Outrage Wins

It is indisputable that in the 2000 Presidential Election, more citizens of Florida went to the polls intending to and believing that they had voted for Al Gore than George W. Bush.

But because of a number of problems with bad ballot design and other issues, over 175,000 ballots were unable to be properly counted. A subsequent analysis showed that had these ballots been interpreted to reflect the likely intent of the voter, Gore would have won the state and the presidency.

But not all of those ballots were counted, and one of the reasons, was the so-called “Brooks Brothers Riot” in which a group of Republican lawyers3 in Florida used violence to shut down the counting of ballots that were likely to be favorable to Al Gore.

The dispute dragged on until the Supreme Court ruled on a partisan vote to end the Florida recount. Al Gore, presumably acting out of principle and recognizing that an ongoing dispute could be damaging to the country, agreed to concede.

Through a combination of violence and technical lawyering that the system affirmed, even though it flew in the face of the underlying principles of the democratic will of the people being paramount when it comes to choosing our elected leaders, George W. Bush became President of the United States.

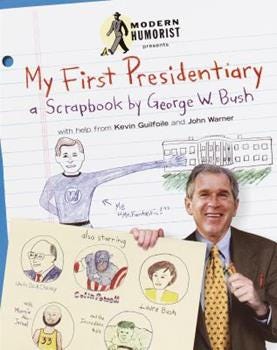

I was upset at the time, but my friend Kevin Guilfoile and I also had a consolation prize in hand in the form of a book contract for My First Presidentiary: A Scrapbook of George W. Bush.

I didn’t imagine that a satire done primarily in colored pencil was going to bring down a president, but I sincerely believed that a sustained attack of truth-telling humor would puncture the bullshit. I spent quite a lot of time during the Bush Administration writing (primarily for Modern Humorist) and editing (for McSweeney’s) pieces that were trying to put some humorous truth into the world.

I suppose the election of Barack Obama felt like a kind of validation, but the victory was pyrrhic, as the forces of outrage gathered for eight years, leading to President Trump and now beyond.

I sometimes wonder what might have happened had Democrats matched the Republican outrage over the Florida recount, if rather than backing down for the good of the country, we instead fought for the good of the country.

The potential counterfactuals of a Gore presidency are too numerous and depressing to consider. Could 9/11 have been prevented with greater continuity from administration to administration? (Possibly.) Would an invasion of Iraq resulted had 9/11 occurred? (Probably not.) Would some kind of climate change legislation have passed putting us in a better position today to battle this existential threat going forward. (Maybe?) Would we have had a President Obama after eight years of President Gore?

President Trump?

🤷♂️

Or if Democrats had matched Republican outrage, back in 2000 would we have experienced something like what seems to be looming - and indeed already happened on January 6, 2021 - a potentially extended violent contested action over who controls the levers of governmental power?

Maybe a full clash of outrage is inevitable, maybe it should’ve already happened, not just in 2000, but when Mitch McConnell denied Democrats a seat on the Supreme Court, or when the Senate twice failed to do the obviously correct thing and convict Donald Trump on charges of impeachment?

I wonder if I am up to the task.

The Exhaustion of Outrage

I knew that if I wrote a newsletter titled something like, “Emily Oster Doesn’t Care How Many Teachers Die,” I could put it out on social media and draw lots of eyeballs and pick up some additional subscribers. My outrage would validate the outrage of others and gather the support of the like-minded.

But this feeling would flame out fairly quickly, and now that I’ve captured this new audience, I would have to feed them some new bit of outrage each week. This is the modus operandi of the anti-CRT movement, which having largely exhausted that fuel, quickly moved on to accusing teachers and librarians of being “groomers” for the transgression of making LGBTQ-themed books accessible to students.

I literally do not feel good physically when I am in the midst of my outrage. Directing this outrage at a person with whom I probably agree on more than I disagree doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Being specifically outraged at Emily Oster when what I’m truly upset about is a deeper sickness in the American culture that validates the economic style of thinking is a route to self-imiseration. I don’t wish Emily Oster harm. I long for a different world.

Outrage may sell, but it’s not my brand, and truly, outrage does nothing to bring people closer to my world view. I want people to agree with me because they think I’m careful and correct, not because we hate the same people.

I also do not want to spend my time outraged.

But as I look at next Tuesday’s election, perhaps one of our last chances to say enough to a culture of outrage at the ballot box, I wonder if I’m going to have to get much more comfortable with outrage in the future.

Links

At the Chicago Tribune this week I break down how massive the Colleen Hoover phenomenon is in publishing terms, and yet how small it remains compared to other forms of media in the broader culture.

To no one’s surprise (certainly not mine) a judge’s ruling has blocked the merger of Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster.

The Washington Post would like you to know about “10 Noteworthy Books for November.”

If you’re looking for a book to give the writer in your life, Vanity Fair has 11 suggestions, including a couple of The Biblioracle favorites, How to Write and Autobiographical Novel by Alexander Chee and I Came All This Way to Meet You by Jami Attenberg.

You might not need this now, but just in case, these are apparently the “5 Best Books on Socrates.”

I sincerely hope no one needs this list now, but unfortunately, we’ll all confront this at some point or another: “Seven Books That Understand Your Grief.”

A great new books podcast launched this week from Michael Hobbes, titled If Books Could Kill, a week-by-week look at the worst airport books of all-time. The first title is none other than Freakonomics.

Recommendations

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $296.25 for the year.4

1. Diary of a Void by Emi Yagi

2. I Can Give You Everything But Love by Gary Indiana

3. Human Blues by Elisa Albert

4. Our Country Friends by Gary Shtenygart

5. Daybook by Anne Truitt

Lucy O. - Portland, ME (but currently Cusco, Peru)

I think Lucy will connect with an unjustly somewhat overlooked book from a few years ago, Dear Fang, With Love by Rufi Thorpe.

1. The Sandman Volume 3 Dream Country by Neil Gaiman

2. Legends and Lattes by Travis Baldree

3. The Spare Man by Mary Robinette Kowal

4. Clark and Division by Naomi Hirahara

5. Grey Moon Over China by Thomas A. Day

Lisa M. - Long Beach, CA

I’m a little out of my depth with this list, but there is a book in this vein from a few years back that I read and enjoyed for both its inventiveness, and the way its interrogation of technology made me think, The Municipalists by Seth Fried.

Fewer than 10% of all subscribers are paid subscribers. If you have been enjoying this newsletter, and have the ability to contribute in order to keep it free for everyone, your help is much appreciated.

That’s it for this week folks. Back to more direct book talk next time, I promise.

Don’t forget to vote if you haven’t already.

JW

The Biblioracle

The people who watched Carson thought he didn’t have any politics because he reflected their politics.

This is in reference to an actual quote from DeVos at the time when she was asked about guns in schools.

Current Supreme Court justices John Roberts and Brett Kavanaugh were not directly involved in the Brooks Brothers Riot, but both made their bones as Republican operatives acting on behalf of the party during the Florida recount.

I’ll match affiliate income up to 5% of annualized revenue for the newsletter, or $500, whichever is larger.