Two pieces of literary news caught my attention this week that I think yield some interesting insights when we consider them together.

The first bit is that Norwegian playwright and novelist Jon Fosse won the Nobel Prize in literature. Some years, I may not even heard of the Nobel laureate until after the announcement, but not only have I heard of Jon Fosse, I wrote a previous newsletter about my contact with the book considered his masterpiece, Septology.

The other piece of news was an announcement that after 35 years of continuous publishing, The Gettysburg Review would cease publishing, a decision carried out unilaterally by Gettysburg College president Robert Iuliano and provost Jamila Bookwala. The decision blindsided the two person paid staff of the review.

The Gettysburg Review is one of the top literary journals in the country, regularly seeing its fiction, poetry and essays being selected for year-end Best American and Pushcart Prize anthologies. For its 35-year existence The Gettysburg Review has served as both a publisher of established writers such as Joyce Carol Oates and E.L. Doctorow and a gateway to new writers. I spent some time this week having a little fun going through past issues and looking for names of writers who’d published in the journal before anyone would have heard of them, and then went on to great things.

Jenny Offill, author of the wonderful novels Dept. of Speculation and Weather has a story in the winter 1995 issue, three full years before the publishing of her first novel Last Things. Charles Yu who would win the National Book Award in 2020 for Interior Chinatown published a story in the summer 2004 issue, two years before the publishing of his first collection of short stories, Third Class Superhero.

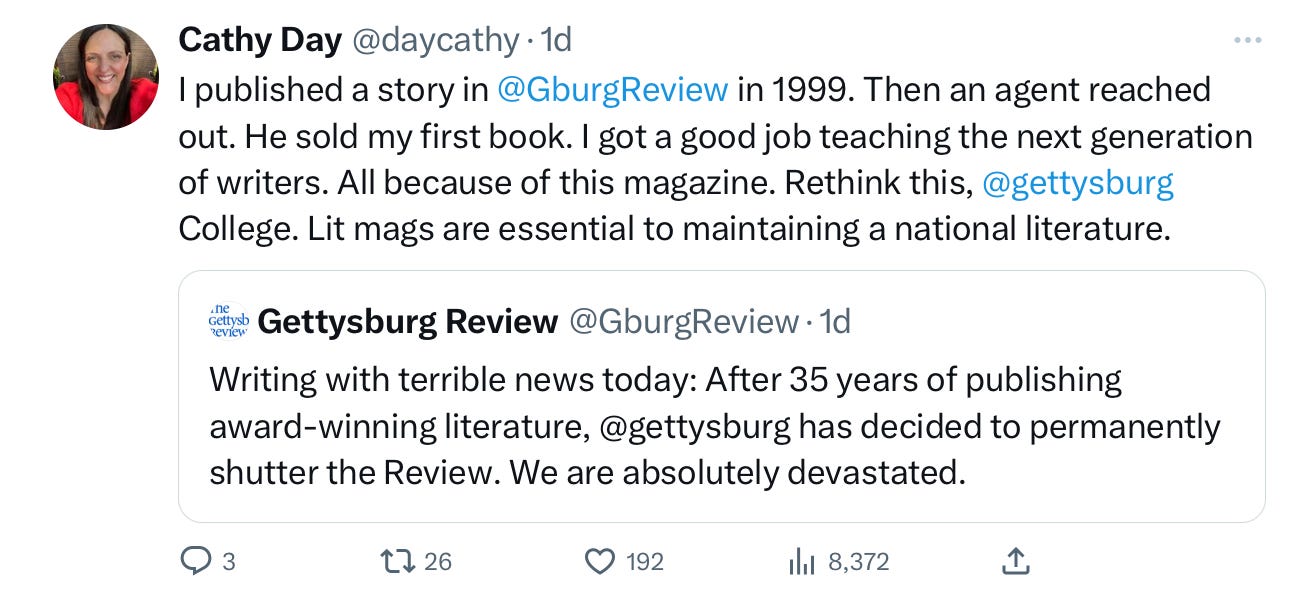

Cathy Day, who wrote one of my all-time favorite linked short story collections, The Circus in Winter, shared her what happened for her after she published a story in The Gettysburg Review.

According to reporting from the Gettysburg student paper (The Gettysburgian) the college’s administration appeared not particularly knowledgeable about the operations or prominence of the The Gettysburg Review. Prior to becoming president of the college, Iuliano was general council of Harvard University and doesn’t appear to have any significant academic background.

Everything Cathy Day says in her tweet about maintaining a national literature is 100% true and the decision of the Gettysburg administration is incredibly short-sighted, as it’s choosing to kill a publication with a national reputation that happens to be attached to a small liberal arts college in rural Pennsylvania. There has been a spirited outcry on social media and elsewhere, but I have to think that the fate of The Gettysburg Review is sealed, as the only thing more embarrassing to the administration than failing to recognize one of the gems of their institution is acknowledging the mistake by backpedaling on the decision they claim was made with great care and deliberation.

If places like Gettysburg College will not subsidize journals like They Gettysburg Review we will not have publications that screen and collect examples of what they believe to be exemplary examples of the various genres.

I subscribed to The Gettysburg Review for a year somewhere in 1996/1997. This was toward the end of my graduate education when I was actively participating in the creative writing marketplace. At the time I felt both an obligation to support activities in the marketplace in a manner I could, and the need to better inform myself of what kinds of wares were succeeding in the marketplace. The Gettysburg Review was a highly regarded journal, but not so highly regarded that it seemed impossible for an unpublished writer to break in.

I’m using the word marketplace, both because it’s accurate and because the ways in which The Gettysburg Review (and journals like it) operate in a marketplace show how those operations are inconsistent with achieving success against the markers of capitalism, e.g, profitability.

There’s markets and there’s markets. There’s no universe in which literary journals are profitable. If the world requires literary journals to take in more revenue than they require to operate there are no literary journals in the world. They must be subsidized either by institutions or through unpaid labor of staff.

Here is the truth: Very few people read The Gettysburg Review. Their publicly available circulation range is between 1000 and 2500 copies, which sounds about right.

Even as a subscriber, I never read an entire issue of The Gettysburg Review, and if I’ve read anything published by them since, it would’ve been in a “best of” anthology. I was looking for intelligence about what they published so I could compete in that marketplace. Sure, I might enjoy or be impressed by what I read, but I wasn’t looking for that. I was trying to achieve something like what Cathy Day describes above, to go from being entirely unknown to on someone’s radar.

I wanted to gain some currency in the creative writing economy that existed inside academia. This was tangential to commercial publishing in that many people inside the creative writing economy published commercially, but the vast majority of the creative writing economy did not make their living solely through income from their writing, but who knows? It could happen. It did happen for some. Mostly though, you’re after that professor gig, so you can teach, continue to publish in literary journals, then a book, tenure, another book, promotion, and you’ve got a nice life immersed in things you care about, not rich probably, but at least secure.

Over time, this market has gotten out of whack. When Cathy Day and I went to grad school there were somewhere around 100 graduate programs in creative writing. Now, there’s more than 350, closer to 400. The connective tissue between the journals and a route to an agent and commercial publishing became a bit more frayed as the marketplace became saturated with hopefuls and the money available to literary fiction writers in commercial publishing shrunk dramatically. I would be surprised if many careers in commercial publishing are launched from writers being discovered in literary journals by agents and publishers.

The only currency in the creative writing marketplace became those professoring jobs, which were also shrinking as an increasing number of those teaching jobs became contingent non-tenure track positions which, as I can tell you from personal experience, are not stable and secure.

Ultimately, the academic creative writing economy becomes its own thing, almost entirely separate from commercial publishing. Occasionally folks will leap free of academia on the backs of a big prize or Reese or Oprah pick, and sometimes a writer who started on a commercial path but didn’t get sufficient traction will find a landing spot in academia, but these two markets are increasingly separate.

When it comes to writers making a living from their writing, there is no middle class in this country. According to a recent Authors Guild survey written up at Publishers Weekly, the median book income in 2022 for “established” authors (writers who had published at least one book by 2018) was $12,000. Add in book-related work and that median income moves up to just over $23,000 a year. `

However, the median book income for the top 10% of the established authors was $275,000 a year. Not shabby, but also only 10% of the people who are considered full-time writers by the industry itself.

That middle class of writers needs subsidizing or it doesn’t exist. The chief subsidy is the academic creative writing industry, of which The Gettysburg Review plays a small, but important part.

Speaking personally, this is not a great thing for either market. The academic creative writing market becomes increasingly insular, publishing for other people in the market, rather than interested outside audiences who are not also selling their wares. I have seen young writers thinking of their work strategically in terms of getting it past editors at these journals, rather than giving themselves over to writing what they’re interested in as best they can. This is usually a recipe for failure on all fronts.

I don’t think there’s any deliberate intention to make literary fiction of the kind small journals publish elitist, but the system ultimately results in this work only being seen by an elite. Not an economic elite, by any means, just a self-selecting group sheltered from the commercial market by carving out a different kind of market of their own.

There are many amazing writers publishing in these journals whose books will find homes in university or independent presses. Unfortunately, this is not a national literature, but a literature which a relatively select few ever access. It’s better that it exists than it doesn’t exist, but if the goal of a system is supposed to be oriented around fostering a national literature, it’s problematic that maintaining this market falls on a whole bunch of entities like Gettysburg College to support these important mini-insitutions . As soon as some bottom line administrator who doesn’t understand the status of a publication, or doesn’t care about that kind of status shows up, poof!…there it goes.

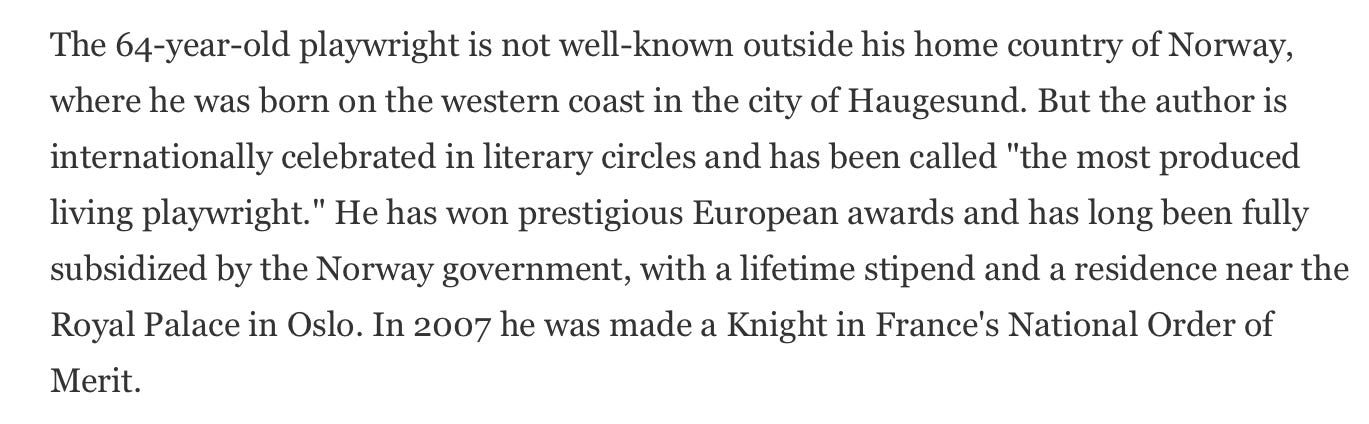

The truth is, we don’t have a national literature, but you know who does?

Norway.

I snipped this paragraph from the NPR write up of Fosse’s winning of the Nobel Prize:

“…has long been fully subsidized by the Norway government, with a lifetime stipend and a residence near the Royal Palace in Oslo.”

Like the United States, Norway is a wealthy country, but it uses its resources in a very different way, one of which is direct government support of the arts, something that simply does not happen in the U.S.

(After my trip earlier this year I wrote a short post at Inside Higher Ed about the Norwegian system of education and parental leave. In spirit, it’s almost the polar opposite of how the U.S. system is organized.)

The idea that the United States government might start subsidizing writers in a way that allows for a middle class of us outside of academia or the other small clutch that can find sufficient traction on private “platforms” like Substack is beyond fanciful. The impact this has on the kind of literature that’s published and the kind of people who get to participate is fairly obvious. One way or another you’re going to have to compete in a marketplace that is not actually oriented around being creative, around exploring something new, around making fresh and surprising art.

Writers in this country managed to produce lots of amazing things despite these realities, but we should not forget that it’s despite these realities.

Since government help is not on the way, if we’re going to have a national literature, it’s up to the commercial interests to build an underlying foundation for this work that is - in the immediate sense - untethered from profit. The cost of running a literary journal like The Gettysburg Review is truly minuscule measured against the budget of a Big 5 commercial publisher. Even a few million dollars a year sprinkled around to the existing journals or incentivizing the starting of new ones would be a huge boost to the work of building a foundation for a national literature.

Publishers should see it as an investment in improving the quality of the atmosphere for the overall health of the products they sell. If you declare these things are valuable and put resources behind them, who knows, maybe people will start to believe you?

Links

This week’s Chicago Tribune column is about a very rare occurrence for me, spending more than two weeks reading a single book. In this case it’s Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting.

LitHub has 27 books they recommend for October reading.

Adrienne Westenfeld at Esquire has her favorite books of the fall.

If you’re looking for a critical overview of Jon Fosse’s work, here’s something from Randy Boyagoda in the New York Times.

At McSweeney’s “Things That Count as Writing” by Janine Annett.

Recommendations

Another week where I’m fresh out of requests that aren’t earmarked for the Tribune column, which gets first priority. So follow the directions at the link below if you want a custom, one-of-a-kind book recommendation based on the last five books you’ve read, click on the link below.

If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, please consider sharing it with other readers.

If you’d like to read more installments of this newsletter, the easiest thing to do is subscribe.

That’s all for me this week. I’ll see you all next time.

JW

The Gettysburgian continues to probe the discontinuation of The Gettysburg Review. The college president sticks to a bunch of consultant-speak talking points. https://gettysburgian.com/2023/10/the-college-administration-addresses-budgetary-constraints/

I love The Circus in Winter! I was struck by that since we seldom seem to have reading interests in common.

Yeah, the idea of the US supporting literature in any meaningful way is rather laughable. It's fascinating to hear how different it can be in other countries.