Later this summer Mrs. Biblioracle and I are going on a trip to Norway.

Fjords, y’all!

Anyway, in preparation, I’ve been reading Septology by Norwegian writer and dramatist Jon Fosse, a six volume novel written in a single continuous sentence.

Writing about Fosse in the New Yorker, scholar and critic Merve Emre said of Septology, “Septology is the only novel I have read that has made me believe in the reality of the divine, as the fourteenth-century theologian Meister Eckhart, whom Fosse has read intently, describes it: 'It is in darkness that one finds the light, so when we are in sorrow, then this light is nearest of all to us.'"

Sounds good to me, even though I had to read it a couple of times to take it all in. There’s a reason the New Yorker isn’t knocking on my door for critical essays on literature. Well, there’s lots of reasons, but that I truthfully know a thimbleful of stuff compared to a true scholar and writer like Merve Emre is one of them.

Septology is the story of Asle, a painter who lives alone on the coast and another painter, also named Asle who lives in the city and is an alcoholic. As I read it, they are different versions of the same person, juxtaposed in order to highlight certain existential questions. It’s not one of those books where you’re going to grasp every last thing, at least I’m not, but that’s okay, books are to be experienced, not “understood” and thus far, it’s been a rewarding experience.

I’d never heard of Fosse prior to reading Emre’s profile, but given that I knew I was going to Norway I figured why not take an opportunity to casually drop the book into conversation so I can come across as the extremely cultured, not at all pretentious a-hole that I am?

I am reading the book very piecemeal because it is the kind of book it takes a good amount of time to read no matter what, and I do not have the kind of life that allows me to spend weeks reading a single book. Given that it is very difficult to find a good stopping point in a book that is written in a continuous sentence, it has been surprisingly easy to get back into the book when I pick it up.

Or maybe it isn’t surprising because there’s something about the sentences that carries me along for the fifteen or twenty minutes I spend with it most days.

There’s a long tradition of long sentences in narrative. My graduate school professor John Wood enjoyed reading the conclusion of Molly Bloom’s soliloquy from the last chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses out loud to us in class as it ends in a kind of ecstasy.

I was a Flower of the mountain yes when I put the rose in my hair like the Andalusian girls used or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish Wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.

The entire chapter consists of eight sentences, and for all the challenge that Fosse presents with Septology, it’s a cakewalk compared to Ulysses, a book I’m not sure that I would’ve persisted with had it not been part of a class, learning alongside my colleagues, guided by a professor.

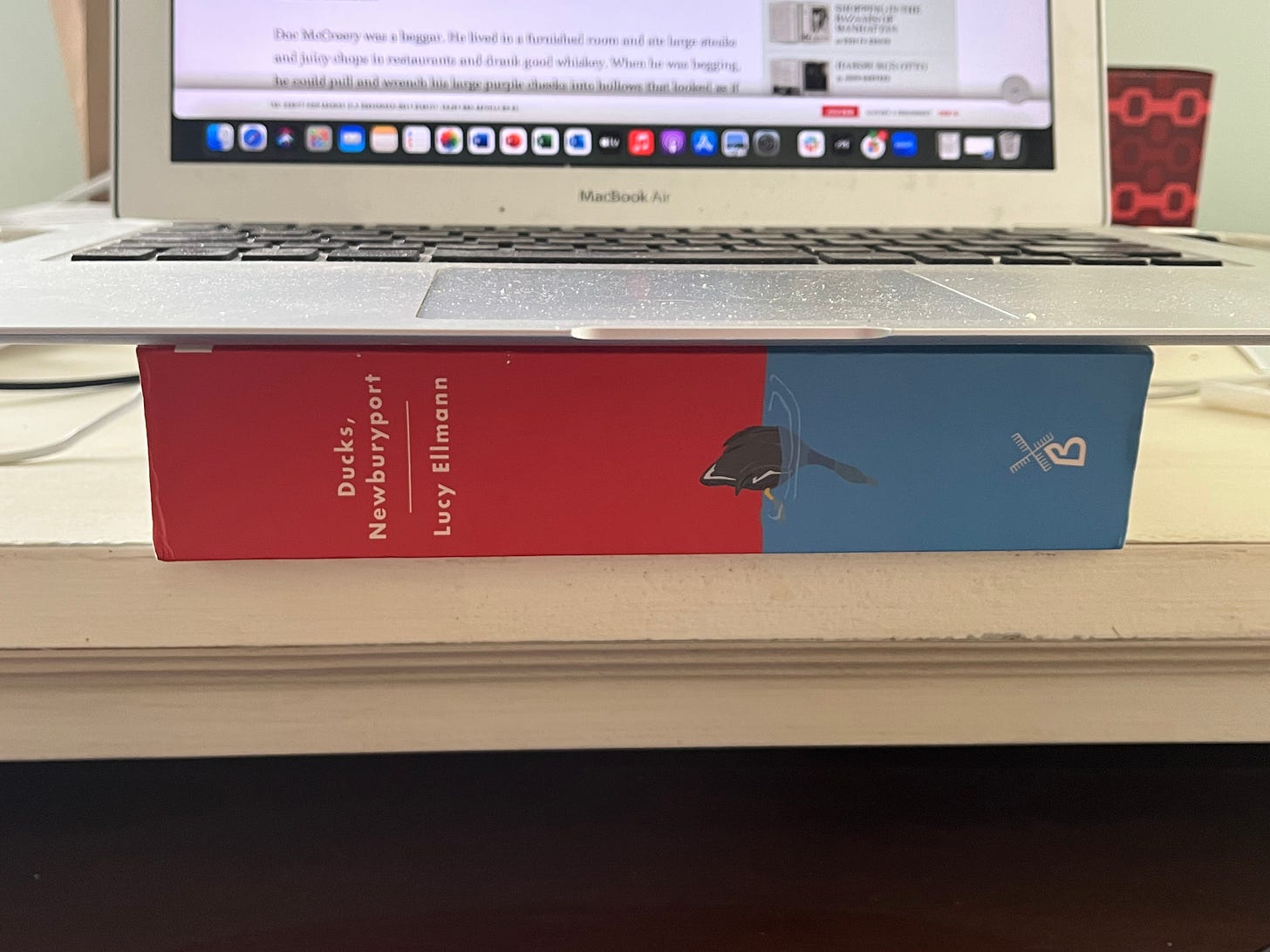

I’m actually also part of the way through another very long book, much of which is written in a continuous sentence, Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann. I read the first 300 or so of it’s more than 1000 pages when I first picked it up, but then in a pinch started using it for a different purpose.

When I got a new desk with a keyboard drawer, to try out the setup, I needed something to elevate the laptop and Ducks, Newburyport was the handiest thing available. It worked so well, I set it up this way even when we moved houses last year. Periodically when I have to wait out a laptop freeze or rebooting process I’ll take the book out and read a page or two, but I still have a long way to go.

Ducks, Newburyport is excellent, a ranging monologue from the point of view of an Ohio housewife on a world - our world - gone mad. It is truly a tour de force. My understanding is that the ending builds to quite a payoff (as does Ulysses), so I’m planning on getting there eventually.

When you ask someone what they loved about a book, they usually say things like the characters or the story. Sometimes they’ll say that it was really “well-written” but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re thinking about the specifics of the sentences, which is weird because every book is made of sentences, and if the sentences aren’t right, the book probably isn’t any good.

Of course what’s right about a sentence depends on what’s right for the story. I think of sentences like I think of drummers. John Bonham, Gene Krupa and Meg White (of The White Stripes) are all great drummers, but they’re not much alike. Their playing fits the music exactly so.

I don’t recall when I really started to like get “into” sentences, but every day I experience a moment where I encounter a sentence that just gets me. Some days, lately, it’s Septology. I’ve also been reading an advance copy of Lydia Kiesling’s next novel, Mobility, which is written in an unadorned style, but the sentences are just perfect.

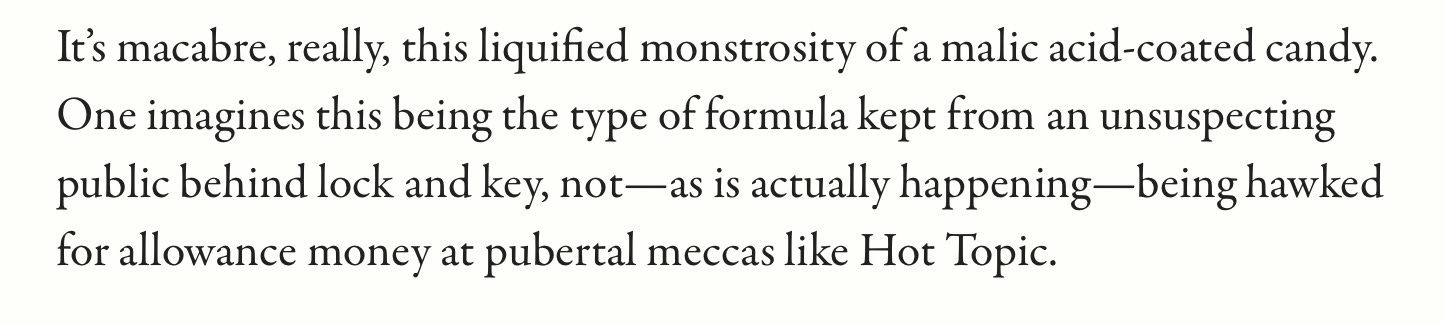

But other days it could be something seemingly silly, like this review of new food at McSweeney’s by Laura Foody writing about “Warheads Sour Soda,” a product that is clearly an abomination just from the name, which contains this gem of a paragraph:

I love all of it, but I’m especially taken by “pubertal meccas like Hot Topic.” Nobody has written that phrase before. Put it in quotes and search it on Google if you don’t believe me. I haven’t, but I’m confident it’s true. There’s something amazing about that, and this is one of the reasons I am bullish on human beings’ ability to continue to outpace ChatGPT. The only way ChatGPT wins is if we allow our pleasures to be defined down to what the AI can do, rather than to continue to revel in what humans make.

After Martin Amis passed, a short clip of him being interviewed by Charlie Rose made the rounds on social media in which he talks about his “war against cliche,” which eventually became the title of a collection of his essays. Writing literature is to make war against he deadening effect of a world where we mostly encounter cliche.

Amis illustrates by saying, “Whenever you write, ‘the heat was stifling’ or ‘she rummaged in her handbag,’ this is dead freight.”

These are perfectly cromulent phrasings, but they’re no better than that. He goes on to say that, “What cliche is, is herd writing, herd thinking, and herd feeling. And the writer, you’ve got to look for weight of voice and freshness, and make it your own. This is what writers do.”

Amis was famously celebrated for his prose, justifiably so. Even when other aspects of his novels were malformed or shambling, the sentences were sufficiently alive to make for a worthwhile experience.

I make no claims as to the quality of my sentences. In all honesty, most of what I publish for audiences is done on the kind of schedule that does not allow for the line-by-line crafting Amis’s oeuvre demonstrates. At the very least, I try to make my writing sound like me, sound human, and not be overly concerned with rules or correctness if it interferes with that goal.

Having spent many years working with beginning students on their writing, I can say that most struggle with this, though every semester there’s a student or two or three whose voices are irrepressible. The most common student move is to try to sound erudite in order to create a simulation of intelligence through a kind of elevated diction. It’s a performance that has often been rewarded in the past, but something I try to cure them of.

I do this by not teaching grammar, but instead focusing on sentences, the subject of a much earlier post at this newsletter:

The students who realize that they have given themselves little to work with in terms of honing their own writing through close work with sentence making because they’ve primarily strung together all the “expected” words start to recognize there’s greater pleasures to be had in personal expression.

This is often at odds with the values that attach to their writing in other courses, but screw it, it’s my class, and I’m confident I’m right about this stuff, even more confident when I see GPT’s simulated writing and observe how dead it is.

Sentences have purpose, but they are not purely utilitarian. Septology is an experience that reminds me of this truth.

Books That Relate to the Topic that I Couldn’t Fit In

Speaking of Merve Emre, as I did toward the top of the newsletter, her book, The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing, is a really interesting combination of research, analysis and cultural commentary.

I don’t have to read the other hot contemporary novelist out of Norway prior to the trip, because I already have! A few years ago I went on a fairly brief, intense Knausgaard trip where I read the first three volumes of his six-volume autofiction opus My Struggle. There was a stretch in there where I almost couldn’t read anything else, but after finishing the third volume, I realized I’d had enough and have had no compulsion to keep going.

If you’re interested in a book that helps you better appreciate what sentences do, and how they work, let me recommend Stanley Fish’s How to Write a Sentence: And How to Read One, which is a sort of extended lecture (or series of lectures) from the legendary literature scholar that models the close attention that can be paid to sentences.

Links

At the Chicago Tribune this week, I list seven non-beach read books for the summer, none of which were published in 2023, all of which deserve to be read, year-after-year.

If you’re looking for a bigger, somewhat more traditional list of beach reads concentrating on newly released books, the Chicago Tribune has you covered on that front as well, with 52 books to recommend for the summer season.

Vulture would like to tell you about the 14 books they can’t wait to read this summer.

The Booker Prize people have a list of a dozen books to read in honor of Pride Month.

Here’s an interesting read about the author Ann Rule, and the birth of true crime writing, from Laura Miller writing at Slate.

Recommendations

All books linked here go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and the Teacher Salary Project which is advocating to establish a federal minimum salary for teachers of $60,000 per year. Affiliate income is $129.00 for the year.

1. How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy by Jenny Odell

2. Self-Portrait with Cephalopod by Kathryn Smith

3. Why We're Polarized by Ezra Klein

4. Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes

5. Affinities by Brian Dillon

Mark N. - Poulsbo, WA

Mostly nonfiction here that seeks to peer beneath the surface of the world. I’m going to go with a novel that does this in a way that combines both wonderful essaying, and compelling fictional storytelling, The Guest Lecture by Martin Riker.

Exit Question

I have to ask about your own favorite sentence makers. Who do you love? Why? Whose sentences should I be appreciating that I might not be aware of? Drop a thought in the comments. It’s fun!

Alrighty, folks. That’s a wrap. Until next time I am…

John

The Biblioracle

The first thing I thought of was the opening of Light Years by James Salter, which begins:

"We dash the black river, its flats smooth as stone. Not a ship, not a dinghy, not one cry of white. The water lies broken, cracked from the wind. This great estuary is wide, endless. The river is brackish, blue with the cold. It passes beneath us blurring. The sea birds hang above it, they wheel, disappear. We flash the wide river, a dream of the past. The deeps fall behind, the bottom is paling the surface, we rush by the shallows, boats beached for winter, desolate piers. And on wings like the gulls, soar up, turn, look back."

Salter's second paragraph is just as good.

Music critic Amanda Petrusich makes stellar sentences all the time. Her recent tribute to Tina Turner is one example; but the one I come back to again and again is her loving farewell to John Prine, which ends like this:

"Prine had one of those faces that doesn’t come along very often—beautiful, rutted, expressive. He always looked just a little bemused, in part because his eyes were narrowed and slightly arched, curled into a sort of permanent smile. It takes an exceptionally kind-hearted person to sing the whole messy, stupid story of what it means to be human—the cruel and indulgent things we do, the way that we love—and make it sound so logical. I don’t know if there’s a word for what people felt when they saw him play; it’s the kind of soft gratitude that wells up when you look at someone and feel only thankful that they exist, and that you got to breathe the same air for a little while. Those losses are the hardest to metabolize. But it helps to think of Prine in the heaven he imagined, which is the heaven he deserves."

P.S.

The rest of Ducks, Newburyport is fantastic, by the way. It took me a while to find its frequency, but once I did, I thought it was spellbinding.

Reading just now:

We understand the encoding of genetic sequences, the folding of proteins to construct the cells of the body, and even a good deal about how epigenetic switches control these processes. And yet we still do not understand what happens when we read a sentence. Meaning is not neuronal calculus in the brain, or the careful smudges of ink on a page, or the areas of light and dark on a screen. Meaning has no mass or charge. It occupies no space-and yet meaning makes a difference in the world.

-Dr. Ha Nguyen, How Oceans Think