This past week, legislation requiring public schools to display the Ten Commandments in school classrooms was signed into law by the governor of Louisiana.

I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, John, that sounds totally unconstitutional. And it is! For now. The braintrust behind the law is looking forward to taking their case to this Supreme Court, which they think may not be such sticklers about the Establishment Clause. Current governor Jeff Landry has pretty much openly declared his intention to turn Louisiana into a Christianist state.

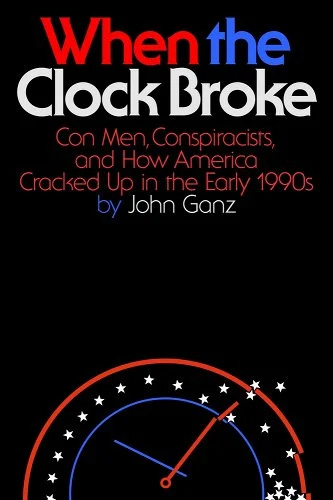

As coincidence would have it, the news out of Louisiana coincided with me starting to read

’s new book, When the Clock Broke: Con Men, Conspiracists, and How America Cracked Up in the Early 1990s. The book is an examination of various political figures and movements of the era and how our present politics of a clearly fraying democracy can be traced, often directly, to this earlier time.The first chapter examines David Duke, the Klansman who achieved state-level elected office in Louisiana before turning his sights on bigger game. I particularly appreciated Ganz’s characterization of the state’s political climate as a place in which an overt white supremacist could find electoral favor:

“Perhaps Louisiana provides particularly fertile soil for the emergence of a candidate with a Neo-Nazi past. Justice Brandeis may have famously called the states ‘the laboratories of democracy,’ but the alluvial plains and dense swampland of the Mississippi Delta were less like a lab that a hothouse or Petri dish of inchoate American fascism.”

A bit later, after running through a laundry list of post-Civil War antidemocratic occurrences, Ganz continues:

“[In Louisiana} tyranny coexisted with a certain kind of anarchy. The state’s experiments in antidemocratic rule sat atop a society that was exceptionally underdeveloped and poor as well as extraordinary fractious and difficult to lead….W.E.B. DuBois called the state’s politics ‘a Chinese puzzle’ and a witch’s cauldron of political chicanery.’ The cauldron simmered with a constant roil of corruption, lawlessness, and mob violence…”

As Ganz illustrates, Louisiana has never been much concerned about democracy and the Constitution, other than as instruments through which to wield power. (If this reminds you of attitudes that seem common among the broader Republican political structure, that’s not coincidental.) Ganz quotes Huey P. Long, the demagogue Trump was oft compared to during the 2016 election, a man who was just as corrupt and venial as Trump while also being far more competent. Long said of his state, “There is no dictatorship in Louisiana. There is perfect democracy there, and when you have perfect democracy it is pretty hard to tell it from a dictatorship.”

I wouldn’t call myself an expert in Louisiana’s politics, but I did live in Lake Charles for three years (1994-1997) during graduate school, and I also had a very specific experience with the quasi-fascist state when the weight of the law came down upon me, and I was sentenced by a duly elected judge to attend church once a week for a year.1

I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, John, that sounds totally unconstitutional, and that’s the thing, it didn’t matter. It was simply the way of doing things.

The story starts one morning as I was driving to school, and the 35MPH surface road I had taken every day for a year was blocked off for no apparent reason, funneling us to a different route. It was early, maybe 7:15am, and I was on autopilot. I don’t know that I’d ever even driven on this other street, two lanes heading each direction with a large median of trees between them, practically a boulevard. Suddenly, a figure in spandex shorts and a bike helmet jumped out from behind the bushes and into the street, arm outstretched, signaling me to stop. As I got closer, I saw that this was a bike cop and I should not swerve around some maniac waylaying drivers. I stopped, rolled down my window and was told that I’d been clocked going 35 in a school zone by their compatriot up the road.

I did not know I was in a school zone because the sign signaling the start of the school zone was further up the road than where I’d been required to start my detour. The school was on the opposite side of the road, mostly obscured by the tree-lined median. The ticket itself had been pre-written with the exception of my license information, which the bike cop filled in, telling me I had the right to an in-person adjudication as they handed it over. The whole thing took a couple of minutes, a kind of planned entrapment for the sufficiently unaware. I wasn’t even late for school.

Once at school, I took a look at the fine if I pled guilty without making a court appearance and saw that it was in excess of $400, more than double my monthly rent at the time.2 I figured I’d roll the dice on going to court. How much worse could it get?

When I arrived at the municipal court on my appointed day and saw the literally hundreds of other people milling around, I despaired, thinking it would take all day to work through the case log. I was wrong. Once the judge was seated, while acknowledging that we had a right to contest the charges against us, the fine work of the local constabulary made it unlikely we would prevail and we should know that our choice to contest, should we be unsuccessful, would result in additional court costs on top of the statutory fine.3

There was, however, an alternative. We were all eligible for “probation,” which required one condition, going to church every single week for a period of one-year. The judge asked who would be opting for a trial. I saw no one raise their hands.

Next the judge asked who would like to just pay their existing fine? A few hands were raised.

Probation? Hundreds of hands (including mine) went into the air. We were directed to the front of the courtroom where a clerk would have the paperwork ready for us to sign, along with handing out our signature cards.4

Our probation was fulfilled by having a church official sign our card each week, and then at the end of the month, we were to send our card to the Court. I had never been a regular churchgoer, considered myself a non-believer, and the prospect of waking early on Sundays to attend a service for a faith I did not believe in did not fill me with joy, but the alternative of paying that fine was worse. Maybe I’d see some interesting stuff at least.

Over the course of my probation period, I went to thirty-some different places of worship, including a Pentecostal tent-revival replete with snake charming and speaking in tongues, a Christian Scientist service where I was the only non-member present, one Catholic mass (services were too long for my taste), and maybe a dozen different Baptist denominations. I was politely declined by the local Mormon temple because I did not have a sponsoring member who could profess to the sincerity of my seeking. (Fair enough.)

Most of the services were uneventful, unmoving, and I would fight sleep from my place in the pews. The church probation option was so common that some of the churches had a pre-made stamp for our cards.

There were a few memorable moments, however. A number of the Baptist services were focused on the problem of temptation and the need for female purity so men would not fall from grace. Apparently every woman, and even some girls, has an inner Jezebel, waiting to bring a good man low.

One service veered into an elaborate New World Order conspiracy theory involving the Clintons and current UN Secretary General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali. The most vivid detail I recall from that sermon was that if we did not resist we would be getting barcode tattoos on our forearms so we could be tracked by the government. Our Second Amendment rights were very important to preventing this outcome.

Awake and out of the house earlier than I would’ve been otherwise on a Sunday, I started chasing my time at the places of worship with sessions at the local riverboat casinos where I would play blackjack. Armed with knowledge gleaned from The World’s Greatest Blackjack Book by Lance Humble and Carl Cooper, I employed a system predicated on consistency and discipline.

Never bring more than a $100 stake. Bet no more than $5 per hand.

Play the Humble/Cooper strategy completely faithfully.

If the stake is lost, leave. If, at any point, I had doubled my stake, leave. Leave after two hours, no matter how I was doing.

The riverboat casinos of Lake Charles, Louisiana were not inspiring places. Crowds were thin on Sunday mornings. Most of the players were South Asian immigrants grimly playing like it was their job. The drinks were watered down, but I had Cokes, so it didn’t matter. The riverboats almost never left the docks, but to stay in compliance with the law, there were periods where you’d be barred from coming and going as though we were tooling around the lake.

Even with faithful employment of the Humble/Cooper strategy, the house would maintain an advantage - but a slim one - and my willingness to walk away when I was up meant that over the course of a year, maybe 30 or so sessions, I was net positive, around $400.5 Most of the time I would spend my two hours hovering no more than $20 from even one way or another. A couple of times I lost my stake in under 15 minutes.

But there was also one glorious Easter Sunday where I walked out with more than $100, and it felt like divine intervention.

I’d deliberately chosen the megachurch in nearby Sulphur, Louisiana because it shared a parking lot with one of the casinos, underneath an array of power lines/transformers that stretched for half a football field. Church, gambling, and radiation, the real stuff of America. I sat deep in the balcony of the well-appointed 3000-seat theater, far more opulent than anything that would await me at the casino later.

The sermon’s theme was, as expected, a recounting of Jesus’s trial and crucifixion at the hands of the Romans, but I had never heard the story recounted in such vivid detail before. The preacher, almost moved to tears by the image he’d conjured for himself, told us how Jesus’s “muscled back glistened in the sun under the lash of Roman whips…”

The BDSM/homoerotic subtext was so overt it seemed to no longer be subtext. But just as no one seemed bothered by sermons about how twelve-year-olds could be blamed for tempting grown men to “sin,” or that the UN was going to enslave us as part of a one-world government, no one seemed troubled by the preacher talking about how Jesus’s “thighs flared under the weight of the cross.”6

Here was Buff Jesus, brought to life by the preacher in Sulphur, Louisiana, eventually to become a right wing meme. We were left with the impression that at any moment, had he wished, Jesus could have thrown off his shackles, climbed down from that cross and kicked some serious ass, but he didn’t because he loved us so much he knew he had to die for our sins.

I honestly didn’t know what to make of any of this at the time, other than I was totally weirded out by all of it. With hindsight, it seems pretty simple, these people were happiest to cede their biggest picture concerns to an authority who was willing to tell them what they needed to hear to make sense of the world. That I found all this senseless was a strong testament to my outsider status. If I’d been from there, I would’ve understood.

In When the Clock Broke, Ganz reminds us that David Duke, a neo-Nazi white supremacist, won a majority of the white vote in Louisiana in every single one of his races. When asked why they liked him, people often said something along the lines of, He says what I think.

After the service, alone, I walked across the parking lot to the riverboat, put one of my twenty, $5 chips that represented my stake on a spot, and was promptly dealt two aces. Following the guidelines in The World’s Greatest Blackjack Book, I both split and doubled down on what were now two hands, meaning I had a fifth of my stake riding on one go-round. The dealer graced those aces with two face cards. Two blackjacks, which paid 1.5 to 1 meaning I was up $30 after one hand of $5 dollar minimum blackjack.

I won the next five hands in a row with the dealer busting every single time, up another $25. Another blackjack, add $7.50 for a total of $62.50. I’d been at the table less than 10 minutes. It was Easter Sunday, I’d heard a very strange sermon, it was April of my final year of grad school with a month or so to go and literally nothing on my horizon. I broke my no more than $5 per hand rule, putting $20 on the next deal.

A pair of 8’s. Humble and Cooper are very clear in The World’s Greatest Blackjack Book, always split 8’s. 16 is a bad number in blackjack and you must avoid it. I split the 8’s. The first 8 was painted with a face card for an 18 that I would hold no matter what. The second 8 received ANOTHER 8! I split again because you always split 8’s. I now had $60 riding on the hand.

The second 8 got a 4, I hit again for a 5, total 17 which I would hold. The dealer was showing a 7 and I began to hope that there was a face card in the hole, meaning I’d escape with one winner, one push, and then whatever the third hand had in store.

The third 8 got a face card. I was sitting on 18,17,18 with a dealer 7 showing. I had not internalized enough of The World’s Greatest Blackjack Book to know what my odds were, but they weren’t great.

The dealer flipped the hole card, another 7 for a 14 total. Things were looking up. An ace or 2 and they’d have to hit again, an even greater chance at busting. A 3 meant I would win 2 out of 3 bets. A 4, I would lose one bet and push two, not great, but an escape next to the worst case scenario, which was a 5, 6, or 7, any of which would send all three bets down the tubes. Eight and above I would win all three.

I was vibrating with anxiety. The dealer snapped down a 2. I had just enough time to gasp before it was followed with a face card, busting the dealer. Another $60 to the good, $122.50 up overall. I sat at the table, bowing out from the next two hands while I got my shit together. I fell back on the plan, tipped the dealer and left the casino.

I only went back to the boats one more time before graduating, and my ledger says I lost $15. At the time I left Lake Charles for good I still had one more church attendance card to complete, but once back in Chicago I never went to church again, and wouldn’t have known how to explain the cards anyway.

A couple of years later when I had to renew my license in Illinois I was paranoid that I wouldn’t be able to do it because I was wanted in Louisiana. It wasn’t a problem. At some point, mail arrived to my parents’ house saying that my conviction had been vacated because the judge had been impeached for improper conduct. I don’t know the details. Maybe the ALCU sued over sentencing thousands of people to church.

Many years later, there was a glimmer of an opportunity to return to teach at my graduate alma mater, but thankfully, I’d yoked myself to Mrs. Biblioracle’s far superior career opportunities and it wasn’t even a moment’s temptation. I’d had a great three years there and the people of the region and state I’d met were mostly wonderful, but those things were immaterial to the deep history of the state, the forces John Ganz maps to the popularity of figures like Huey Long and David Duke.

I knew it was a strange and dangerous place.

Maybe that’s true of everywhere now, though.

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I wrote about Gillian Linden’s strange and powerful new novel, Negative Space.

Vital piece from Julia Carpenter, writing at Esquire, on the censorship of books in prisons.

At LitHub,

explores how more and more it seems like authors are feeling compelled to finance their own marketing campaigns for their books. This is a temptation I’m trying not to give in to, but it feels like if I don’t, maybe I’m missing out on my chance to make a leap.This week via McSweeney’s, “We Love the Character of This Neighborhood, So We Bought a House, Tore it Down, and Build a Mansion Resembling a LaQuinta Inn,” by Aaron Applegate.

Recommendations

1. I Have Some Questions For You by Rebecca Makkai

2. Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome

3. The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett

4. The Running Grave by Robert Galbraith

5. How To Stop Worrying and Start Living by Dale Carnegie

Nadya - Düsseldorf, Germany

Nadya likes stuff with some mystery to it. I’m recommending

’s Sunburn as a good fit.1. Tell by Jonathan Buckley

2. SPRAWL by Danielle Dutton

3. The Instructions by Adam Levin

4. One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses by Lucy Corin

5. Cold Enough for Snow Jessica Au

Mark N - Poulsbo WA

Okay, normally I wouldn’t do this because I’ve already mentioned this book above, but I’d really to know what someone with this reading profile would make of it, Negative Space by Gillian Linden7

Louisiana Books

I don’t know that any book could explain Louisiana, but there’s some classics that I should mention, Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men, his fictionalized treatment of Huey Long. I’m obligated also to mention A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole. Very much in the spirit of that book is Bill Cotter’s Fever Chart, a wonderful comic novel of madness. Arlie Russell Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right is a sociological study of Lake Charles itself drawn from fieldwork prior to the election of Donald Trump, and published a couple of months before Trump’s election in 2016 that illuminates the forces that drove his victory and which may put him back in the White House.

And last, but not least, Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer is just a perfect novel.

Any Louisiana books that you can recommend?

Well, I had no idea this was going to come out when I was planning this week. I hope it was too indulgent.

See you next week.

John

The Biblioracle

I have told this story to numerous friends and acquaintances over the years since its initiation in 1996, but I’ve never put it into print. It’s possible that I’ve allowed some measure of personal lore to creep into the tale, but I do have a handful of contemporaneous notes that I’ve relied on and some of the occurrences are indelible enough to make an enduring impression.

I was living in one-half of a shotgun duplex at the time, a structure that would be torn down within five years of my graduation. My phone bill from staying in touch with the woman who would one day be Mrs. Biblioracle was higher than my rent.

Going ten over the limit on a residential street normally would’ve been like a $50 dollar fine. Doing it in a school zone involved a statute that created a significant multiplier. Had I been going 34, the bike cop would never have left his hiding spot in the bushes.

We also had to pay something like $50 “bail” which I suppose could be returned, in theory, once probation was completed.

I kept a ledger to keep myself honest.

These notes I took on the back of my signature card.

All books (with the occasional exception) linked throughout the newsletter go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and an additional reading/writing/literacy nonprofit to be determined. Affiliate income for this year is $79.00.

In my view, Ernest J. Gaines is one of the best ever novelists about Louisiana. In particular, I would recommend “A Gathering of Old Men” and “Lessons Before Dying.” I lived and worked in Louisiana from 1993 to 2006, and I picked my first death penalty jury in Lake Charles in 1995. Everything you say rings entirely true to me. Sadly, the pendulum seems to be swinging there in an ever more dangerous direction once again.

I lived in Baton Rouge for 2 years in the 80s. My husband taught English at LSU. I made him leave before his contract was up to move back to Chicago. I don’t even like going to New Orleans. Learned about Huey Long and was called a Yankee for the only time in my life. Also visited a plantation where the old way of life was loved; they wanted to go back to the good times.

Lucinda Williams has some beautiful songs about Louisiana and her memoir is beautiful also.