As I imagine many of you know, the Writers Guild of America (WGA), the union representing writers for television and movies is on strike.

I’m a friend to laborers in all their shapes and sizes, and while I’m not naive enough to believe that labor unions are beyond reproach, they are the best mechanism we have for sharing the pie with the people who do most of the actual baking.

I’m not a member of WGA and don’t ever anticipate becoming one, but as a writer I have an appreciation for the kind of work WGA members do. I also have many friends and acquaintances who are WGA members, so for all of those reasons, and some others, I strongly support the labor action and hope they get every last thing they deserve, which is a lot.

But before we part ways this week, I hope to convince you why you too should support the writers of the WGA, and how what’s happening is merely one example of a larger phenomenon that has already claimed many victims and harmed society overall.

There’s lots of good explainers about why the WGA is striking, like here, here, and here, but in a nutshell, the rise of streaming has allowed studios to horde revenues without sharing it with the writers and other professionals who work to bring those productions to life. The pre-streaming era contracts which outline requirements for staffing on shows in production and residuals paid out for re-airings are not suited to a world where the audience metrics are kept secret by the studios and streamers. Writers’ whose shows may be on a streaming platform, potentially being watched my millions of people are sometimes getting paid as though they’ve aired only once.

The result has been to turn something that used to be a “job,” where employment was steady and predictable to a “gig” that is inherently precarious. This has happened against a backdrop where studios are making billions of dollars of profit.

Turning what once used to be steady jobs into low-paid, precarious gigs is something I do have a little personal experience with.

If you told ten-year-old me who was reading almost the entirety of the Chicago Tribune (save the Business section, because, yuck) on a daily basis that I’d spend 11 years (and counting) writing a weekly Sunday column for that newspaper, I would’ve assumed that writing this column was my job and through this job I was able to support myself and even a family.

Friends, I could not. My weekly Sunday newspaper column is just one of the many gigs that I use to cobble together my living. By itself, it would barely keep me out of poverty. In some sense, I should be grateful, given that when I started I was part of a 24-page stand-alone book section (Printers Row), my column just one of many different books-related features. Now, many Sundays I am the entire extent of the original books coverage in one of the largest newspapers in the country. The fact that I am a relatively low-paid freelancer and therefore a very small line item on the budget is likely a chief reason why I’m still around.

The story that newspapers were disrupted by the Internet triggering the collapse in advertising revenue (primarily classified ads, which used to power a good chunk of the enterprise) is true, but what many people don’t realize is that even following this shift newspapers were profitable businesses.

No, they were not as profitable as the tech companies that had now entered the landscape. Or rather, their stock valuations were not as high as the tech companies that had now entered the landscape because many of those tech companies were not actually profitable and their stock prices reflected bets on the future outcomes for those companies. Rather than running a quality, modestly profitable newspaper, the goal at the top of the corporate structure became to goose the stock price as much as possible. Profitability was part of the equation for what pleased investors, but it certainly wasn’t everything.

For example, the New York Times bought the money-losing digital sports publication The Athletic for $550 million in early 2022, taking a fairly significant short term hit to their bottom line as part of their business strategy built around revenue from paying subscribers, as opposed to relying on advertising.

When it comes to news, this is a bet that the Times had already won, a colossus astride the rest of the digital news universe with somewhere around 10 million subscribers. In 2022 it posted an operating profit of nearly $350 million. This would have been even higher except that The Athletic has lost $36 million since being acquired by the Times. Even the New York Times is not allowed to just be a newspaper attempting to pursue its 4th estate purpose.

In 2021, the private equity firm Alden Capital took over majority control of the Chicago Tribune after being the single largest shareholder since 2019. At the time of Alden taking over majority control, Tribune newspapers were producing a 10 to 13% profit per year. Alden’s goal was to double that. Their method for achieving this was to cut the number of newsroom journalists by over 20%. The non-union editorial staff was significantly reduced as well, with many of the most experienced employees leaving.

As part of the purchasing of majority control, Alden Capital “borrowed” $278 million, a debt which was transferred the the newspaper’s balance sheets. Sixty million of that was borrowed from Alden itself at an interest rate of 13%, during a period of historically low interest rates.

The newspaper had been turned into a financial engine, stripped for immediate gain and left to operate on shoestring budgets. Those that still work on the paper do the best they can, better than that even, but there is only so much that can be done. That a newspaper might have a role beyond generating profits for a small handful of financiers appears to not have been much of a consideration in deciding how the paper was going to operate under their new owners. The existence of the Tribune labor union and its protection of journalist jobs is the primary reason the paper can still do journalism at all.

Journalism has largely become a gig. Layoffs have hit just about every newspaper and magazine across the country, including relatively large scale, one-time high flying digital publications like Buzzfeed News. Some of these individuals have been able to decamp to platforms like Substack where they can try to make a living as self-employed gig workers, but this is no way to run an industry that at least in theory has a public purpose beyond its business operations.

Unfortunately, there is no going back. Once an institution has eroded, the best you can hope to do is pick up the pieces and rebuild something in its place as best you can. When I started this newsletter, I described it as a potential “lifeboat” in case my column was axed.

It has become more than that, and I’m pleased with how far it’s come and quite proud about what I publish here, but my posts here receive, on average, between 5000 and 10,000 views. In contrast, the Sunday Chicago Tribune has a circulation of several hundred thousand copies.

Some writers on this platform (like me) make enough for the time spent writing to be not just a fulfilling personal act, but a reasonable business proposition, one of the gigs that aggregate into a living. A tiny handful make far larger sums than they could have ever hoped working in traditional journalism, high six and seven figure salaries. But even those writers have significantly smaller audiences than they would were they published in traditional newspapers. Virtually all of these folks have achieved this because they previously established their audiences and reputations as part of collective publications like newspapers and magazines.

The range of what audiences may be exposed to has shrunk. Substacks are not made available in libraries or indexed in databases. Every bit of “content” is behind a wall, accessible to only those who can pay. (Okay, not my content because I’m a dummy who believes in a patronage model that makes content as open as possible, but the smart people who are playing by the rules of the game wall off their content.)

Making the work of journalism or cultural production through television and film inherently precarious is simply bad for society. The proposal from the WGA members would cost studios approximately $429 million extra in the hands of the collective of 20,000 union members on an annual basis. In 2022, eight of the studio/stream CEOs pocketed a collective $228 million dollars all by themselves.

This concentration of wealth does nothing to benefit the consumers of film and television, the same way Alden Capital and their ilk’s ownership of print media enterprises does nothing for readers of newspapers. It is pure extraction, extraction of the money we as consumers put into the system.

And of course, looming over all of this is generative artificial intelligence like OpenAI’s GPT. You can bet that the studio executives are salivating over the idea that an algorithm can do the bulk, if not all of the work of writing, shrinking the need for human labor even further.

I happen to think that’s an absurd idea and have no wish to live in a media landscape with content created by an algorithm with no capacity for thought or intention. I want to experience the weird stuff that other human intelligences bring into the world, not algorithm-generated product.

A successful strike by the WGA is a necessity in order to balance how resources are apportioned as to the making of film and television. This is really the first of more battles to come as other unions involved with film and TV production will have to have similar fights in order to get their fair share. Writing at his newsletter,

describes the labor movement as "the coral reef of humanity encircling the rapacious pirate vessels of commerce," and I think that’s exactly right. Yes, Hollywood writers, when properly compensated, are well-paid, but why shouldn’t this be the case? What they do takes enormous skill and hard work. The odds of success are not great, and this is the kind of success that we should be valuing in this country of ours. We should certainly value it more highly than the ability to do a little financial engineering that allows you to extract millions of dollars out of a legacy industry. The writers are never going to be paid like the financiers, but we should not begrudge a single dime of what they are able to secure for themselves.The good news is that unlike journalism, or higher education (another example I could speak to at length that has been hollowed out by similar forces), there is more than enough money to go around in film and television to keep things humming along nicely for everyone involved.

Whenever you hear news about striking WGA members, rather than accepting a framing that the writers are preventing the production of your favorite show, perhaps instead think of it as executives hoarding money that could instead go into making those shows as good as possible.

Above all, do not be dopey like this:

Humans write things. Algorithms assemble syntax. For the love of all that’s holy, I’m pleading with people to at least value their own humanity, if not the humanity of others.

Great Books About Television

I am a sucker for oral histories that go deep into the inner workings of cultural phenomena, and Live from New York: The Complete, Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live as Told by Its Stars, Writers, and Guests by James Andrew Miller and Tom Shales does the job on what is now one of the longest running shows in the history of television and one on which good writing is indispensable. If you’re a fan of The Wire, see also All The Pieces Matter: The Inside Story of the Wire by Jonathan Abrams.

Jennifer Keishin Armstrong has written biographies of several shows including Sex in the City and Seinfeld, and I’ve read them all, but my favorite is Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted: And All the Brilliant Minds Who Made the Mary Tyler Moore Show a Classic as it tells the story of a true shift in television history, a show with a female lead who wasn’t primarily seen through the lens of being a wife and mother. The MTMS also spawned a generation of female TV writers whose work continues to resonate today.

Written by New York Times critic Jason Zinoman, Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night is really now the story of a bygone era. Zinoman is obviously respectful of Letterman’s accomplishments, but the book is no hagiography and features its share of Letterman’s warts, warts he now spends a lot of time acknowledging as America’s Santa-bearded evolved male authority figure on his Netflix interview show.

For a totally different perspective on what it’s like to make a career as a writer in Hollywood, I recommend Nell Scovell’s Just the Funny Parts: ... and a Few Hard Truths about Sneaking Into the Hollywood Boys' Club, which is entertainingly written, but also unflinching about the sexism and harassment Scovell negotiated throughout a decades-long career, including a sting at Letterman’s late night show.

Great Books About the Movies

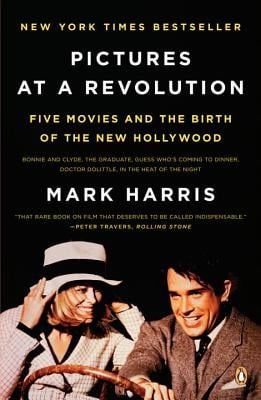

Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood by Mark Harris is a fascinating dive into a single year when five movies, (Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, in the Heat of the Night and Doctor Dolittle) signaled a new era of Hollywood. Not only a behind the scenes look at what happened and why, but a deep analysis of what film means in the lives of the audience. Also highly recommended is Harris’ biography of legendary director, Mike Nichols, Mike Nichols: A Life.

Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting is a book that captures the romance and absurdity of making your living writing for the movies by one of the great screenwriters of all time, William Goldman (who is also author of The Princess Bride). My first copy of this book was used, and so tattered the binding split down the middle before I was done reading it.

Probably better known via its film adaptation directed by Robert Altman, The Player by Michael Tolkin captures the same mordant, dark humor on the page. A satisfying mystery and satire at the same time.

Blue Movie was written by Terry Southern, who is better known as the screenwriter of Dr. Strangelove and Easy Rider. But Southern was a rather uhh…unique novelist who uses extreme situations as launching points for (sometimes scatological) satire. In Blue Movie, a former Oscar-winning director is exiled to Liechtenstein where he is commissioned to create the biggest budget X-rated movie in the history of cinema. Not a book for everyone, but if you did Dr. Strangelove, you might enjoy Southern’s novels (including The Magic ChristIan and Candy (co-authored with Mason Hoffenberg), a gender-flipped version of Candide.

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I share my appreciation for what has become a renaissance of books coverage at Esquire magazine. Just in time for my column, Esquire editor Adrienne Westenfeld shared her top books for spring.

The Chicago Review of Books also has their top books for May 2023. The New York Times also has a list of new May books.

My home state of Illinois has passed a law to ban book bannings.

This week’s appropriately themed piece from my friends at McSweeney’s: “Excerpts from AI-Written Rom-Coms that Prove Human Writers Are Obsolete” by Martti Nelson.

I could (and should) recommend every episode of Brad Listi’s Otherppl podcast, but I want to especially recommend this episode with my old friend Dave Eggers talking about his new book, The Eyes and the Impossible, and lots of other stuff as well, particularly what it’s like to put your head down and just do the work.

Recommendations

All books linked here go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and the Teacher Salary Project which is advocating to establish a federal minimum salary for teachers of $60,000 per year. Affiliate income is $102.30 for the year.

1. The Book of Goose by Yiyun Lee

2. Trust by Hernan Diaz

3. Liberation Day by George Saunders

4. The Privileges by Jonathan Dee

5. Dance Dance Dance by Haruki Murakami

Jeff G - Charleston SC

Because this has been a widely read book for a fair bit of time, there’s a decent chance the Jeff has read it, but if he hasn’t read it, it’s an oversight that must be remedied because it is so far up his alley, Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell. (If he has read it, he should email me and let me recommend another book as a mulligan.)

1. Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

2. O, Beautiful by Jung Yun

3. Home is Not a Country by Safia Elhillo

4. The Bear by Andrew Krivak

5. The Court Dancer by Shin Kyung-Sook

Natasha A. - North Charleston, SC

I think Natasha will be taken with the incantatory prose and disorienting fable world of Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi.

Thanks, as always, for reading. For this week’s exit question for the comments a two-parter: First, please share your favorite books about television and film; second, what television shows and movies do you think are particularly well-written, where it seems clear to you that the care taken with the script is doing a significant part of the work in creating the high quality end product?

Yours in solidarity,

John

The Biblioracle

Well-written TV show: Star Trek Discovery seasons 1 & 2. I’m not sure I can distinguish the writing from the things you sew (probably a good thing), but the story is the best I’ve experienced on TV and in Star Trek.

I loved Dickinson on apple tv. It's self consciously a bit corny and sincere and uses anachronisms to make the characters, real historical people, feel more like real people