Consumers v. Patrons

The market will always win, but sometimes we can resist just a little, and be better for it.

In the wake last week’s newsletter on the Penguin Random House/Simon & Schuster anti-trust trial, I’ve spent a fair bit of time this week thinking how irrational it is to even attempt to write, publish, distribute, and sell books. Because I’m a writer, I’ve been thinking about the irrationality of writing books, but the whole shebang is just bonkers.

Like, is everyone aware that just about every single book inside a bookstore can be returned to the publisher for a full refund pretty much at any time?1 For lots of books, the number of copies “sold” peaks on the day it’s released and slowly shrinks as unbought copies are returned to the publisher. My co-author, Kevin Guilfoile and I, experienced this big-time when our Bush-era parody My First Presidentiary: A Scrapbook of George W. Bush was returned en masse from every bookstore in the country following the 9/11 attacks. Almost 30,000 copies were sent back, taken to a warehouse in New Jersey, and shortly thereafter “pulped” for tax reasons.

The fact that there were even that many copies remaining in the world for a book released in January of 2001, and whose sales had already slowed to a trickle, shows the challenges of book distribution when you have what is in most cases a niche product, that you nonetheless have to put in thousands of stores spread across the country because there’s (if you’re lucky) a small handful of people who want your book in any given place.2

Again, with few exceptions, prior to being published, the ultimate sales fate of a book is a near total unknown. This is true even of books that receive large advances. Consider the raft of books by former Trump administration insiders, some of which garnered seven-million dollar advances, that have largely tanked, sales-wise. 3

A big part of the fault lies in what I talked about last week, the inherent backwards-looking nature of publishers when they decide what to put into the world. They saw big sales for books by John Bolton and James Comey and thought there must be a market for insider accounts of the Trump administration, but the limits of that market should have been obvious.

How many different ways are there to say that the man is a raving maniac?

Anyway, to reiterate: The structure and economics of publishing make absolutely no sense as a business at any level. We pretend that this isn’t the case, but as the PRH/S&S trial turned to what happens to books that go up for “auction,” it became clear that all the valuations attached to particular books are simply made up. If a publisher decides they want a book, they just keep offering more until they have it. PRH, the company with the biggest war chest, is the winner most often. If it absorbs Simon & Schuster, it will win even more often. The merger itself is a highly rational move to create an entity that is simply larger, capable of making more big bets, reaping the rewards of the good guesses, and being better cushioned for the bad ones.

This same dynamic attaches to the decisions of individual writers to write a book. Writing a book is making a bet - against the odds - that you will produce something that is not only good, but that also someone else in a position to bring the book into the world will think is good, and then want to invest their resources in making that happen.

(This dynamic is being somewhat disrupted by self-publishing and crowdfunding, but even as popular as this has become, it remains a very small part of the broader publishing world.)

I honestly know very few writers who spend much of any time thinking about the money they may make from writing a book when they decide to write a book. This is a good thing, because if someone were to make the calculation of the economic proposition before writing a book, very few books would ever get written.

Oh, in idle moments you may dream about the outcomes that seem possible, if not exactly probable - a little buzz from early reviews maybe, good word of mouth, and by god, what if someone like Jenna Bush - or, be still my heart - Reese Witherspoon finds out about your book and chooses it for their book club?

It would be like winning the lottery!

Except you’re not going to win the lottery. No, I know, people do win the lottery, someone had the winning ticket for that gabillion dollar Powerball jackpot recently, but seriously, you’re not going to win the lottery.

Your book is going to meet the fate of most books, and be barely read. Reportedly one-percent of books sell more than 5000 copies.

And here’s the more important thing to recognize. Publishing is not a lottery. There is not a random draw for which books rise above the fray to garner attention, and which sink to obscurity. Lots of resources go towards trying to get Jenna Bush and Reese Witherspoon to notice one’s books. If those resources are not attached to your book, it is not going to happen. Even if those resources are attached to your book, it’s probably not going to happen.

At the same time, publishing is not a meritocracy. There is nothing in the system that makes sure only the “best” books get published or get noticed. That said, the most successful writers are the ones who exhaust their potential to make their books as good as possible. This does not necessarily change the odds, but it does mean that if fortune smiles, and opportunity arrives, you have the best chance of taking advantage of it.

But no, none of it makes sense. Hard work is not necessarily rewarded. Some of the cream sinks to to the bottom. Even bucking the odds and writing a book that secures publication likely results in pennies per hour of work.

If publishing is a market, it makes no sense for individuals to try to enter it. Big publishers can make lots of bets on individual books. Writers may spend years on a project, only to see it come to literally nothing.

But they do it anyway. This will never cease to amaze me.

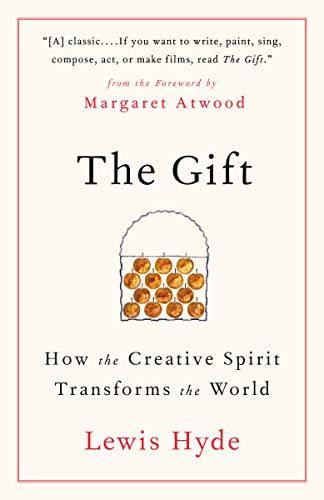

How and why this is happens is the terrain that Lewis Hyde explores in The Gift: The Artist and Creativity in the Modern World, one of the books I mentioned few weeks ago as an antidote to thinking like an economist. Hyde argues that art exists as a kind of “gift” from the artist to the culture, and because the culture values art, it finds a way to sustain itself. The reason books (the ones that are not obviously positioned as products) get written has nothing to do with the market, even if those books must ultimately come in contact with a market. (I’m oversimplifying, but close enough for the present discussion.)

Hyde explores a dilemma, in his words, “How, if art is essentially a gift, is the artist to survive in a society dominated by the market?”

That survival can come in a number of ways. One is for the artist to literally sacrifice themselves for their art, living a life of austerity that allows them the time and space to create. Another path is to support yourself doing something else while using the time remaining for your art. Hyde uses the example of Edward Hopper, the painter of Nighthawks, who worked as a commercial artist for many years while his paintings barely sold. Lastly, you can be funded by wealth that has been garnered from the market economy (your own or others).

While money derived from markets is necessary at some point, the support of the art and artist is not subject to markets, but instead falls under the category of “patronage,” where the artist with the second job is a kind of self-patron. When Markus Dohle, the CEO of Penguin Random House said at the trial, “We are angel investors in our authors and their dreams, their stories. That’s how I call my editors and publishers: angels” he is essentially expressing the ethos of a patron, even though he is in charge of a multi-billion dollar company.

All the publishing imprints that have been gathered underneath the Big Five (Knopf, FSG, Harper, etc…) were once driven largely by a spirit of patronage, as the rich people saw it as their mission to bring culture to the masses in an act of noblesse oblige. Sure, they kept track of how things were going, but profit really wasn’t the driving force.

Even though I think Dohle deserves a bit of side-eye over his deflection away from what the merger would do to the market, in a way, it’s also kind of awesome, a recognition that ultimately all of this is truly sustained by patronage.

The most prominent public patrons of books in my lifetime are Dolly Parton and Oprah Winfrey. Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library has gifted over 185 million books to children. Oprah’s Book Club not only moved millions of copies, but helped build a reading culture are big, literary books. Oprah’s book club episodes were routinely among her lowest rated, but she didn’t care.

It’s interesting to consider how Oprah’s patronage model was eventually subsumed by the market. Reese Witherspoon’s super successful book club runs as part of an overall production company/lifestyle brand/media company that sold for $900 million last year.

But what happens when we shuck off our identities as consumers and instead consider ourselves patrons instead?

On Friday, I picked up my latest haul of books at The Village Bookseller. I’d ordered three and somehow wound up with two more.4 The total retail price for those books was $136.5

Had I purchased these same books from Amazon, I would have paid $106.

That I “overpaid” for these books makes me a bad consumer, but what if instead I look at that extra $30 as a form of patronage? That money helps sustain a local business in my community, owned by a local and employing others. I not only bought some books but engaged in 30 minutes of interesting conversation with the folks at the store. I experienced community and fellowship, things that are difficult to quantify, but which we can easily see as a kind of “gift” (as Hyde would put it) made possible by the creation and existence of the art.

I am in the fortunate position where I can afford to practice this kind of patronage, and because I can, I do, but there is a similar exchange going on when you borrow a book from the library. In fact, libraries are specifically designed to remove the market from the equation entirely, which is why people who use libraries - even though libraries are free - are referred to as “patrons.”

It’s also worth considering what it would be like to have more mechanisms that convert the money made in markets to patronage. Sure, there’s grants and fellowship available for writers, but there are only a handful a year that are truly sufficient to sustain a writer’s work. You also start to notice that the same writers tend to receive those fellowships. Part of this is because they’re genuinely good, part of this is because they have developed the skill of applying successfully for grants, and part of it is that once you get on a bit of a roll financial security wise, there’s more time to seek out and apply for more grants.

The available patronage tends to cluster around proven commodities, a kind of market logic applied to patronage. If we’re going to give someone money to work on their writing, what better way to know they’re good than the fact that they’ve won other fellowships or prizes?

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this, but the limits of such a system of patronage are obvious.

Lewis Hyde is right. The market dominates. Resistance is futile. Accommodation is the only way.

I’m actually attempting to run this newsletter on a patronage model. All of the content is free and subscriptions are purely voluntary, expressions of support for the work that receive no additional goods in exchange. The Substack algorithm tells me that if I made the content exclusive to subscribers, rather than making it free, I would increase my revenue by somewhere around 50%. At the same time, my readership would be maybe 1/8th its current size. I’ve consciously chosen readership over revenue because, A. the additional money wouldn’t really make a significant difference to my day-to-day existence, and B. knowing that I might have a few thousand people read this (as opposed to a few hundred) helps motivate me to do the work.

While I may be attempting to operate this little outpost on a patronage model, it’s important to recognize that Substack, the host for this writing, is not. Early on, in order to lure established writers to the platform, Substack behaved something like a patron, offering some writers guaranteed income, and even subsidizing health insurance costs. Those deals are reportedly now going away, having done their job to lure high profile names to the place.

Substack publicly espouses a mission to empower writers and connect them with readers, and just like Markus Dohle’s declaring that he sees his staff as “angels,” it’s sort of true, Substack does make these connections more possible. There are alternative platforms, but a chief reason I decided to do this was how easy Substack makes it.

But Substack’s mission is meaningless and would (or more likely will) evaporate in an instant once it fails to have sufficient promise in the market. This is why I have to root for their success, even though I do not really believe their high-minded declarations of being in the game to empower writers.

The logic of the market has no time for empowering individuals. Individuals exist to aggregate revenue that feeds the market.

If the market is not pleased, nothing else seems to matter.

Links

Salman Rushdie thankfully appears to be recovering following a horrific attack on stage at an event in Chautauqua, NY.

This week at the Chicago Tribune, I pay tribute to Melissa Bank, author of The Girl’s Guide to Hunting and Fishing who passed away at the too young age of 61.

At Plough, Phil Christman (author of How to Be Normal) rounds up some recent books exploring the apocalypse. Cheery!

We’re just a little over halfway through the year, and PopSugar has already identified more than 100 of the best young adult books for 2022.

What do you think are the 30 most influential children’s books of all time? How does your list match up with BookRiot’s.

The New York Times has a short quiz on how well you know “Midwestern Novels.” I got 100%, natch. (It’s a gift link with my subscription, so everyone can access it.)

At Slate, Laura Miller goes deep on what’s driving the amazing sales of Colleen Hoover’s books.

Recommendations

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $176.10 for the year.6

1. Box 88 by Charles Cumming

2. Judas 62 by Charles Cumming

3. The Palace Papers by Tina Brown

4. Under the Banner of Heaven by Jon Krakauer

5. Portrait of an Unknown Woman by Danial Silva

Terri M. - Gurnee, IL

Terri tells me she’s a sucker for a good spy novel, so I’m hoping she hasn’t yet read Olen Steinhauer’s Milo Weaver series, which starts with The Tourist.

Keep a lookout for the next installment of A Book I Wish More People Knew About, this week. This one comes from a friend and writer who is one of the most frequent recommenders of books that I read.

Gorgeous day where I am. I’m going to go enjoy it…

…by reading outside on a hammock.

JW

The Biblioracle

This practice dates from the Depression era when it was implemented in order to keep bookstores open and publishers publishing. See this article for more interesting history and how it impacts the present.

This is embarrassing to admit, but when my novel, The Funny Man, was published I would periodically go to my local Barnes & Noble to see if any of the copies it had started with (three) had been sold. Answer: No. There were three copies of The Funny Man on the shelf up until there were zero when some algorithm triggered an employee to pull them off the shelf and ship them back to the publisher for a refund.

Not to brag, but if the Bookscan data is accurate, my book on how we need to get rid of the five-paragraph essay has significantly outsold the memoir of Debbie Birx,

The books are: Cyclorama by Adam Langer, Mercury Pictures Presents by Anthony Marra, On Critical Race Theory by Victor Ray, The Last White Man by Mohsin Hamid, and Groundskeeping by Lee Cole, which bookseller Addison has been hand selling to me over two consecutive visits to the store.

In a way, this seems like a lot, but when I think about the many hours of activity and pleasure these books are going to deliver, it’s a serious bargain. Plus, because of my profession, I get to use all my book purchases as a business expense.

I’ll match affiliate income up to 5% of annualized revenue for the newsletter, or $500, whichever is larger.

Thank you, John. This is exactly the post I needed to read today.

re: patronage and Substack... I wish Substack allowed for 1-time donations. I appreciate your work and, honestly, probably won't become a paid subscriber b/c my funds are so tight. (I received a free ticket to live music last night but am still lamenting this morning that I paid $15 for one drink.) But, if Substack allowed and implemented Patreon (or something similar) on the platform, I would absolutely make a $6 donation instead of typing this comment b/c reading this post today is akin to a great conversation with a friend over coffee.

Do you think there's any chance that Substack will ever implement the "make a one-time donation" option? WordPress makes this pretty easy now but I'd rather, like you, stay on Substack.

I figure most young people who want to write (play an instrument, paint, run track,...) will never be able to do it as a career. But I wish I knew of a way that 'patrons' could contribute financially to said young persons to help them keep writing, even for a little while. Something like the Biblioracle Fund for Hopeless Writers. Then someone like you John could redistribute that money to writers as you see fit. Crowdfunding, but not to pick a winner. Aligned with your article, there's no market for this, of course. But I'd love to support it.