Note: This post is beyond the length of many email programs to display in its entirety. To see the full post, please click through to the version on the web.

This past week saw the first meeting of The Bibioracle Book Club, sponsored by The Village Bookseller in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina.

The book was John Williams’ Stoner, and I was pleased to find out that none of the dozen or so participants were previously familiar with it because it’s just more fun that way.

I was anxious because I’ve never participated in a book club before, and here my first experience was in one I was ostensibly supposed to lead. I think it went well. Everyone read the book, the discussion was fun, and as always seems to happen when I talk about books with other readers, I was introduced to ways of looking at a book that I hadn’t considered on my own.

This is particularly surprising given that this is the third or fourth time I’ve read Stoner, versus the first for everyone else, but there you go.

Stoner has had a life as a resurrected cult classic, first published in 1965 to few sales, before having a second life in a 2006 edition published by the New York Review of Books imprint, and also becoming best seller in translation in various European countries. It is the story of William Stoner, only child of a subsistence farming couple in rural Missouri who in 1910 matriculates to the University of Missouri, ostensibly to study agriculture, but falls under the spell of literature after hearing a professor recite a Shakespearean sonnet in class, and goes on to spend the rest of his life studying, and then teaching literature at the university.

The novel’s first paragraph tells the entire story of Stoner’s life:

William Stoner entered the University of Missouri as a freshman in the year 1910, at the age of nineteen. Eight years later during the height of World War I, he received his Doctor of Philosophy Degree and accepted an instructorship at the same University where he taught until his death in 1956. He did not rise above the rank of assistant professor, and few students remembered him with any sharpness after they had taken his courses. When he died his colleagues made a memorial contribution of a medieval manuscript to the University library. This manuscript may still be found in the Rare Books Collection bearing the inscription: “Presented to the Library of the University of Missouri, in memory of William Stoner, Department of English, by his colleagues.

Writing on Stoner at the New Yorker (“The Greatest American Novel You’ve Never Heard of”), Tim Krieder calls it an “anti-Gatsby” story, arguing that rather than seeing Gatsby as the anti-hero and cautionary tale Fitzgerald clearly intended, we instead “all secretly think Gatsby’s pretty cool.”

Stoner, on the other hand, is “an unglamorous, hardworking academic who marries badly, is estranged from his child, drudges away in a dead-end career, dies, and is forgotten: a failure.”

The novel is essentially a series of episodes of glimmers of hope entering Stoner’s life, only to be quickly dashed, Stoner accepting these turns with an near caricature of midwestern stoicism. The novel is sad and tragic, a very different kind of tragic than Gatsby, but also beautiful in its way. When I have taught the novel to classes of young people, many have been frustrated by Stoner’s seeming passivity in the face of challenges to his own happiness and desires. Some see him as a fool.

The consensus of the more mature crowd that is The Biblioracle Book Club is that Stoner is something of a hero in his ability to accept the life he has been given, and find pockets of solace in his studies, his teaching, and a brief, genuine love affair with a graduate student.

When Stoner is on his death bed, having ignored the incipient signs of cancer until it is beyond treatment, Stoner considers his life:

“Dispassionately, reasonably, he contemplated the failure his life must appear to be.”

He ticks off those failures, few friends, a marriage he knew to be a doomed before the end of the honeymoon, a great love he had let go. “What did you expect? He asked himself.”

“What did you expect?” is a refrain through Stoner’s final moments, its intonation changing each time it appears from a kind of bitterness to what Krieder calls a “transcendent serenity” as Stoner’s fingers dance over the cover of the one book he wrote, and he seems to appreciate that life is simply this, a devotion or series of devotions to small things, to living the life that’s available to you.

Stoner’s ability, his willingness to deny his wants becomes a kind of saintly heroism, a trait that is out of step with our prevailing American culture, and one that met with admiration among The Biblioracle Book Club.

I have been thinking about the American condition of wanting. My graduate school professor, Robert Olen Butler, taught us that fiction is the art form of human “yearning,” where yearning is “the deepest level of desire.” As a writer, you tap into this yearning by accessing what Bob calls your “white-hot center,” your unconscious, the place from which you dream.

I will be honest that at times when I was a student I found this stuff frustrating because there wasn’t a lot of actual craft talk about improving your writing. Either you were tapping into your white-hot center or you weren’t, and if you weren’t, no amount of massaging the text was going to help. I have grown more sympathetic to this view over time by thinking of yearning as a proxy for animating your fictional people with the same spirit that drives people in real life, wanting something (love, connection, a Schwinn Stingray with a sparkly banana seat, etc…) and running into difficulties in realizing those wants.

The tension readers experience in reading Stoner is witnessing a man literally deny his wants. It seems almost unnatural, particularly to the contemporary eye. A number of book club participants cited Stoner’s background as the only son of subsistence farmers as a possible source of this spirit. He had been raised in an atmosphere where one cannot expect anything except the next day’s work. Wanting more than this would make little sense. Stoner appears to have no ambition for achieving external recognition or status. At one point, the department chair position becomes available and when it is offered to Stoner, he finds the prospect unimaginable.

This choice later subjects Stoner to some serious grief on multiple fronts. Williams seems to punish Stoner for his lack of ambition and refusal to play the angles of life, but Stoner is undoubtedly the hero of the book. There is little sense that Stoner’s life is meant to be a cautionary tale, a warning to others to make sure to get theirs, no matter what might stand in their way.

It seems to me that one of the central challenges of living in our times is deeper than trying to pursue your desires. It actually starts with trying to figure out what you truly desire in the first place. This is the central premise of my long out-of-print novel, The Funny Man.

(Forgive the indulgence of talking about my own book, that anyone reading this newsletter who isn’t either related to me, or a close personal friend hasn’t read, in this context, but it’s where the old train of thought wants to go this week.)

I wanted to tell the story of a character who gets everything you’re supposed to pursue in life (money, fame, attention, adulation), but who is destroyed in the process. The Funny Man (who is unnamed) is a standup comedian who gets famous on a stupid gimmick and once this happens, more and more success follows, until he is a kind of entertainment colossus, everything he touches turning to gold, until everything, inevitably, turns to shit.

My intention was not just to torture the titular character, but also to illustrate and satirize the hollowness of fame/attention/money as desires we, as Americans, are expected to covet. The satire is often over the top, maybe too much so for its time (2011). It’s been years since I’ve even glanced at the contents, but all this thinking about wanting had me paging through it, and I recalled a section during the height of The Funny Man’s cultural power in which he conceives and produces a show called Kick in the A$$.

Kick in the A$$ is akin to Candid Camera, or its later copy, Boiling Points, except rather than running elaborate pranks, they would instead simply film the show’s lead, Langley (The Funny Man’s butler), sneaking up on people and booting them in the ass, after which they would pay the person who had been booted in the ass $1000. Soon, people were actively trying to get Langley show up to kick them in the ass.

Once Kick in the A$$ proves popular, the competition comes and escalates the violence and the stakes:

The Sweeps Week finale of $uckerPunch, involves “the Rage” disguising himself as an officiant at a wedding, and then cold-cocking the groom, right before he’s set to kiss the bride. The chapter concludes:

When writing the novel, my only intention was to push the satire as far as it would go and then maybe a bit further on top of that, but with a decade-plus of hindsight I see some kind of intent to indict even those of us who are not direct participants in this culture, and instead are mere observers. The novel has a somewhat complicated overlapping structure of multiple timelines, but in the present period of the book, The Funny Man is on trial for murder. He’s come to realize that he’s a pathetic wretch and is regretful. Barry sells him on a novel theory that The Funny Man is “not guilty by reason of celebrity,” essentially arguing that extreme celebrity is a kind of mental defect that leaves the individual incapable of making rational choices and being held accountable for them. Near the end of the novel, Barry rehearses his closing statement for The Funny Man.

Bob Butler is right, that deeply wanting things is what makes us human, but those wants untethered from meaning seem to have the capacity to destroy us as individuals. I think very few of us would freely embrace the life of the subsistence farmer, but perhaps there’s something to the notion of finding a place where you can be at least content thinking only of what the next day brings.

Is this even possible in today’s age?

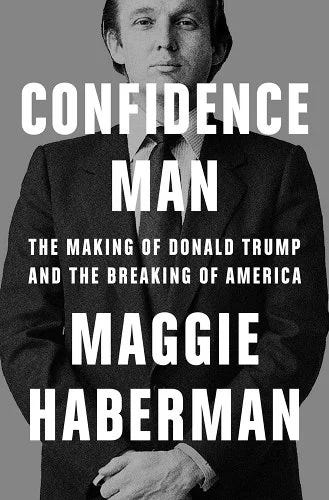

Just as I was getting ready to wrap up this week’s thoughts on wanting, I read Laura Miller’s review of New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman’s Trump tome, Confidence Man at Slate. Miller is one of my favorite critics/reviewers, and one passage struck me with the force of a Ronald “the Rage” Rangini sucker punch:

We’ve all witnessed the handwringing over young people and their quest for attention and approval on social media, and how this is warping their perceptions, but Donald Trump is a 76-year-old man and the ne plus ultra of this phenomenon. Young people who pursue fame and adulation are merely responding to imperatives that have been in place for a long time.

I cut a narrative thread from the manuscript of The Funny Man in which he runs for President that was based in the time Howard Stern (sort-of) ran for governor in New York. I cut it mostly because I couldn’t make the chronology work inside the structure of the novel, but also because it seemed like too much, that mere celebrity couldn’t push that far into something as meaningful as the actual presidency.

In the novel Stoner, the character of William Stoner often sees himself as a kind of ridiculous figure, uninteresting and even unlovable, but the experience of the reader reading the novel proves the opposite is true, that he is a character of integrity and dignity. The novel (deliberately) puts the lie to Williams’ opening paragraph declaring that Stoner is no person of distinction.

Trump is a kind of anti-Stoner, a genuinely ridiculous figure who has been invested by himself - and unfortunately, millions of others - with the status of hero, somehow managing to maintain a colossal, lifelong bluff.

I realize now that the thing I got wrong in the satire of The Funny Man is believing that once you have become such a monster, that there is a route toward renewed self-knowledge, as my character comes to regret his past actions.

I suppose I wanted that fantasy to be true, so I wrote it into being, but events suggest that this was wishful thinking. It seems as though Trump has literally been declared “not guilty by reason of celebrity” by sufficient swaths of the public to make him a once and possibly future President. Indeed, it was Trump’s defense of his own actions in the infamous Access Hollywood tape, that in a healthy society would’ve consigned him to the worst electoral defeat in history, but instead was a mere blip. His actual presidency and post-presidency is simultaneously beyond believing and entirely believable.

The subtitle of Maggie Haberman’s book on Trump is: The Making of Donald Trump, and the Breaking of America.

Just so.

—

Books discussed in this newsletter, linked for purchase at Bookshop.org:

From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction by Robert Olen Butler

Confidence Man: The Making of Donald Trump, and the Breaking of America by Maggie Haberman

Links

My Chicago Tribune column this week is about my appreciation for Elizabeth Stout’s “Lucy Barton Fictional Universe” or the LBFU, which I will admit is not a great acronym.

Here’s your New York Times fifteen books to pay attention to in October, including Confidence Man, and a new collection of George Saunders short stories, Liberation Day.

The Booker Prizes organization is doing a cool thing where they get actors to read short excerpts from the finalist books. This one by David Harewood, reading Percival Everett’s The Trees captures the particular spirit of the book.

We’re officially in spooky season, which means you might benefit from knowing “21 Recent Horror Books You Need to Read Before Halloween” via BuzzFeed.

When Michelle Obama comes to Chicago on her book tour for The Light We Carry, she’ll be interviewed by David Letterman. I guess the email asking me must not have gotten through. It’s not too late to get tickets.

Don’t miss this fascinating article on the book on political change that Barack Obama never wrote that had the working title, Transformative Politics. (That’s a gift link that gets you behind the New York Times paywall.)

Recommendations

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $255.50 for the year1.

1. Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

2. Barchester Towers by Anthony Trollope

3. The Hobbit by JRR Tolkein

4. Joseph Andrews by Henry Fielding

5. Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari

Carol B. - Damascus, Syria

When I see a list of recent reads in the classics, I’m always driven to find a more contemporary book that can match up to what the reader is getting from those well-established tomes. Let’s see how I do by recommending Allan Hollinghurst’s The Sparsholt Affair.

Periodic heartfelt plea for paid subscribers

One of the principles by which I’m attempting to run this newsletter is for readers to primarily think of themselves as patrons, rather than consumers. In the interests of living those values I’ve pledged to keep the content of the newsletter free to all.

Reading (and maybe sharing?) the newsletter is certainly sufficient patronage for everyone, but in some select cases, others are capable of becoming paid subscribers in order to make it possible to keep this content available and provide me with the monetary support that allows me to take the necessary time to produce the newsletter.

If you have been enjoying what you read in this space, and you have the desire and the means, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Of course, right after I ask for more subscribers, I have to issue a warning that it’s possible I’ll have to take next week off because I’m hitting the road to deliver a keynote address at a gathering of writing teachers. Here’s hoping that there’s some quality downtime in an airport somewhere that will give me the opportunity to think and write, but if not, I’ll see you all again the week after next.

All best,

JW

The Biblioracle

I’ll match affiliate income up to 5% of annualized revenue for the newsletter, or $500, whichever is larger.

I read Stoner as part of a reading group several years ago and its simple perfection ruined fiction for me .... I thought I was alone with this feeling until I mentioned it to the guy stacking books at my local Waterstones. He said it had done the same for him. So, yes, an amazing book - but get ready to read non-fiction for a good while afterwards!

OK, 2 comments. First - The whole Stoner/Funny Man discussion is great, timely, and most appropriate for our attention. It's nice to want, but there has to be something behind it, something larger than just the Schwinn Stingray with the glitter banana seat, which, by the way, HOW DID YOU KNOW ABOUT THAT? I was in 6th grade, what can I say. Second - Your column on Lucy Barton and the LBFU. 💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖