In Tuesday’s bonus content Q&A with Kelsey Rae Dimburg, author of the new novel, Snake Oil, commenter JoanP, raised an objection to the term “women’s fiction,” suggesting we should “trash” the term.

It’s a more than fair request which got me thinking about how genre identifiers work (or don’t) in publishing.

Your basic genre classifications - fiction, non-fiction, science fiction, romance, historical fiction, historical non-fiction, biography, memoir - are awfully helpful as ways to break down the vast universe of books into categories that can be approached with some sense. You wouldn’t ask someone which is better, Frank Herbert’s Dune and Ina Garten’s Barefoot Contessa Foolproof: Recipes You Can Trust? It obviously depends on if you’re looking for a story of political intrigue set in a “feudal interstellar society” or an easy way to make a roast chicken for a dinner party of eight.

Even newer categories like “romantasy” or “autofiction” are useful in that they are fundamentally descriptive of the characteristics of the genre. There are no orcs in love in a Karl Ove Knausgaard novel, just as there are no middle-aged Norwegian men in the midst of a simmering mid-life crisis smoking endless numbers of cigarettes in A Court of Thrones.

“Upmarket fiction,” isn’t immediately clear based on just its name, but as I wrote previously, I find the existence of this category, and the specific ways it is like and unlike “literary fiction” hugely helpful when it comes to understanding my own tastes and why upmarket fiction often doesn’t tickle my reading fancy.

But “women’s fiction,” what does that even mean? Fiction about women? For women? As I wrote in another earlier piece it seems as though the way fiction is increasingly being marketed, all fiction that doesn’t involve secret agents or things exploding are for women.

As unhelpful as “women’s fiction” is, it’s perhaps an upgrade over its progenitor, “chick lit” a descriptor that always came with a note of dismissiveness attached, suggesting massive best sellers like Bridget Jones’ Diary, Sex and the City, and Waiting to Exhale were not worthy of the same kind of consideration as novels about the struggles and foibles of men.

Male novelists had been making “art” out of the mess of their lives forever, but for some reason these novels were declared unserious not out of specific aesthetic judgments, but on the basis of their subject matter.

“Women’s fiction” as a fallback position is perhaps preferable to “chick lit,” but that doesn’t mean it’s particularly meaningful so maybe it does deserve to be trashed.

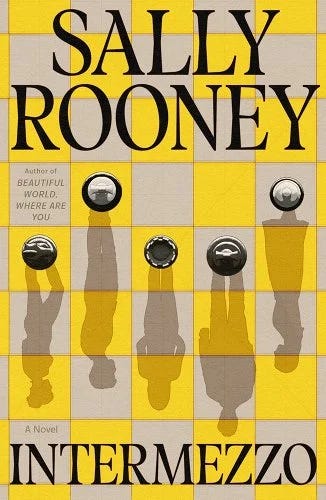

Speaking of novelists who are not described as “women’s fiction” even though the term could fit, I did not even attempt to score an advance copy of Sally Rooney’s impending fourth novel, Intermezzo. They were kept purposefully scarce, and despite writing a column for a legacy publication, I don’t think I would have rated. Apparently, the copies were so precious, the ARCs were stamped with the reviewers’ names to prevent them from winding up in secondhand book shops.

A Sally Rooney novel is one of the very few publishing events in a given year. Midnight release parties are planned on both sides of the pond, and as with her third novel Beautiful World, Where Are You (which had book-themed bucket hats for merch) more unusual promotional tie-ins are planned.

As I wrote at the time of Beautiful World’s release, I got no problem with any of this. I am aware of, and even agree with the objections around marketing overshadowing the work itself, and that these sorts of stunts only further commodify books, distracting from what’s most meaningful - what the books have to say about and to the world - but this sort of thing is so rare, pretty much confined to Rooney at the moment - I figure why not roll with it?

Deep down my approval is probably rooted in the fact that I am a committed Rooney fan. Her first novel Conversations with Friends had me at hello, and I’ve mowed through her subsequent offerings within a day or two of release. I’ve heard and agree with all the objections to Rooney’s novels too. The wonderful critic

has written quite convincingly that the reputation that some readers attach to Rooney’s work is fundamentally at odds with what the books are doing and how the books do those things.I honestly couldn’t tell you if Sally Rooney’s book are of “quality” from a critical perspective. I just like them.

I was pleased to see that novelist and critic Vinson Cunningham is the same kind of Rooney fan as me in this week’s edition of The New Yorker “Critics at Large” podcast in which Cunningham and co-hosts Naomi Fry and Alexandra Schwartz unpack all things Rooney. Like me, despite recognizing the flaws, Cunningham digs the books.

On the podcast, I think it’s Schwartz who suggests that the midnight release parties are a throwback to the Harry Potter release parties of yore, that Rooney’s core readership now would have been Rowling’s readers back in the day.

It’s an interesting theory that I’m willing to buy, a vestigial feeling from a generation of readers stamped by an indelible experience reasserting itself for a novelist who is said to speak uniquely to her generation.

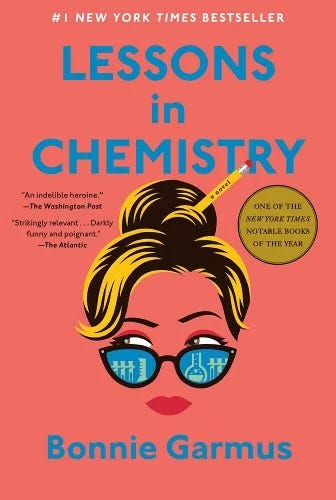

But I also note that as popular as Rooney is - a true best selling novelist - she shifts many fewer units than someone like Colleen Hoover, or recent mega sellers closer in genre to her like Lessons in Chemistry or Where the Crawdads Sing, let alone the once-in-a-century sales phenomenon that was Harry Potter. I’m willing to bet dollars to donuts that very popular literary novelists like Barbara Kingsolver, Ann Patchett, and Celeste Ng all outsell Sally Rooney, but none of them get midnight release parties for their books.

One of the reasons I don’t have the stuff to be a book critic is that when it comes to the books I most love, I don’t have much to say other than…I like it, it’s good.

When you get down to it, every novel is something of a con job where the author is trying to put one over on the reader. We know these people don’t exist, that everything is made up, an illusion. The great thing is that it’s not a cynical con job, but a sincere one, and the first person who has to buy the illusion in the author themselves. I’m continually reminded of the absurdity that is the attempt to write a compelling novel, and I have great appreciation for those attempts, even when they don’t work on me, personally.

What makes an engaging novel so interesting that despite knowing that I’m being conned, the novelist can make us believe, or at least set aside our objections long enough to be absorbed in this alternate consciousness.

I’ve gotta ring up The Village Bookseller and make sure they set aside a copy of Intermezzo for me.

Links

At the Chicago Tribune this week I discuss Louis Moore’s new book, The Great Black Hope: Doug Williams, Vince Evans, and the Making of the Black Quarterback, which opened my eyes to why the Chicago Bears kept Vince Evans on the bench while Bob Avellini couldn’t even throw the ball all the way to the sideline.

In other John Warner does stuff news at Inside Higher Ed, I wrote about how writing is supposed to be hard, that’s the point. You can also hear me on the most recent episode of Bonni Stachowiak’s Teaching in Higher Ed podcast.

Also at the Chicago Tribune, Christopher Borrelli has 44 books to read this fall.

The winners of the Dayton Literary Peace Prize have been announced.

Another piece by

that caught my attention this week is her musings on a corollary to the intentional fallacy, and the argument that a novel can be good by being bad.Via my friends at

, can you believe that we’ve hit the start of decorative gourd season for the 15th time? In honor of the anniversary, you can buy this collectible decorative gourd season beanie.Recommendations

1. Centennial by James Michener

2. The Three-Body Problem trilogy by Cixin Lui

3. Dragon Bones by Michael Crichton

4. Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency (the series) by Douglas Adams

5. Everyone in my Family Has Killed Someone by Benjamin Stevenson

Stephanie K. - Johnstown, CO

I’m going to lean into the wit plus mystery angle and recommend Lisa Lutz’s The Spellman Files.

1. The Wedding People by Alison Espach

2. The History of Sound by Ben Shattuck

3. The Secret History by Donna Tartt

4. Less by Andrew Sean Greer

5. A Prayer for the Crown-Shy by Becky Chambers

Braeden N. - Houston, TX.

I feel like this is a very The Biblioracle Recommends-inspired list, so I hope I make a good fit with it. How about a little comedic misanthropy via Mordecai Richler’s Barney’s Version?1

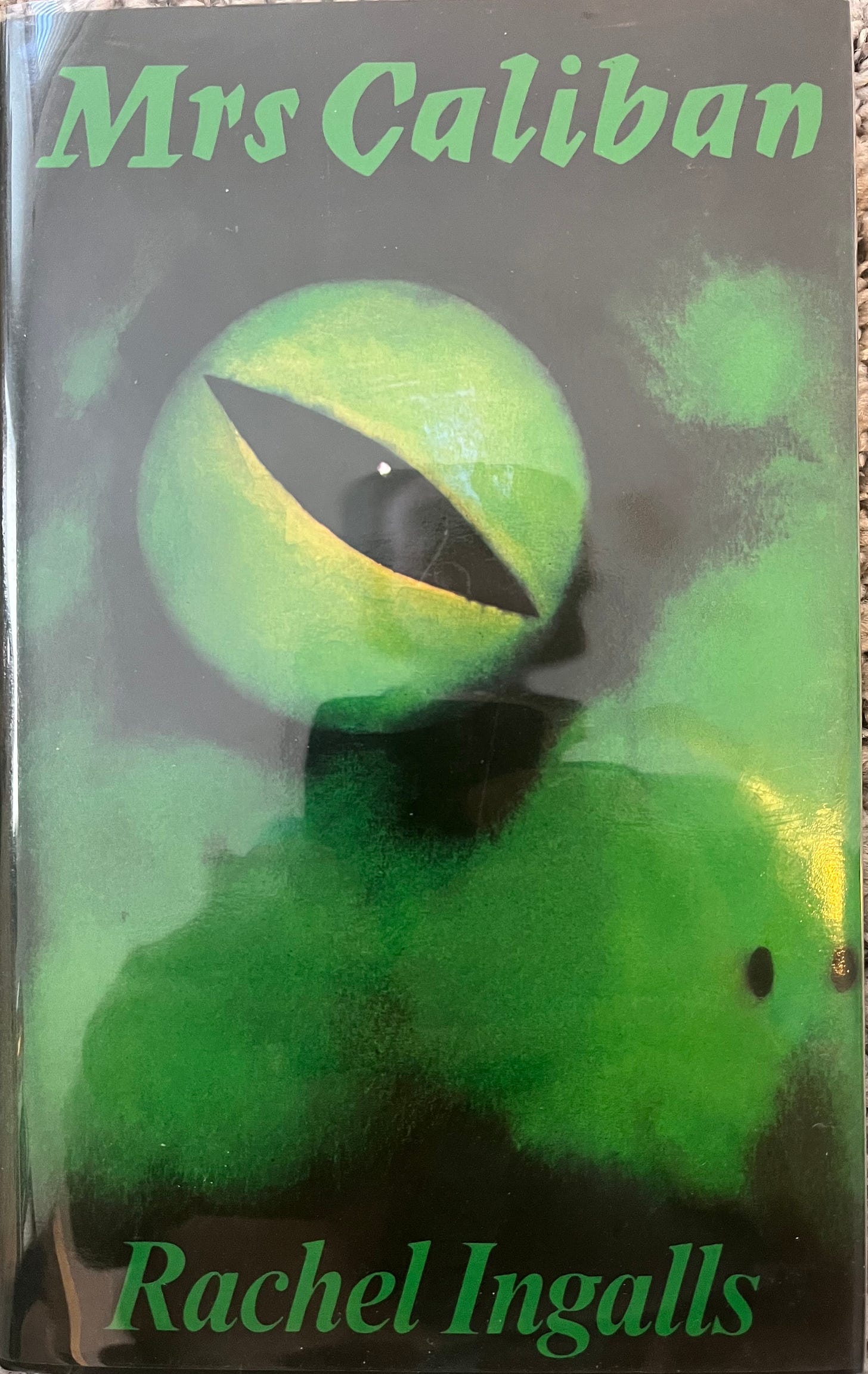

I only came away with one souvenir on Mrs. Biblioracle’s and my trip to London, a British first edition of one of my favorite little novels, scored at Peter Harrington, which had many more desirable editions that were well out of my price range.

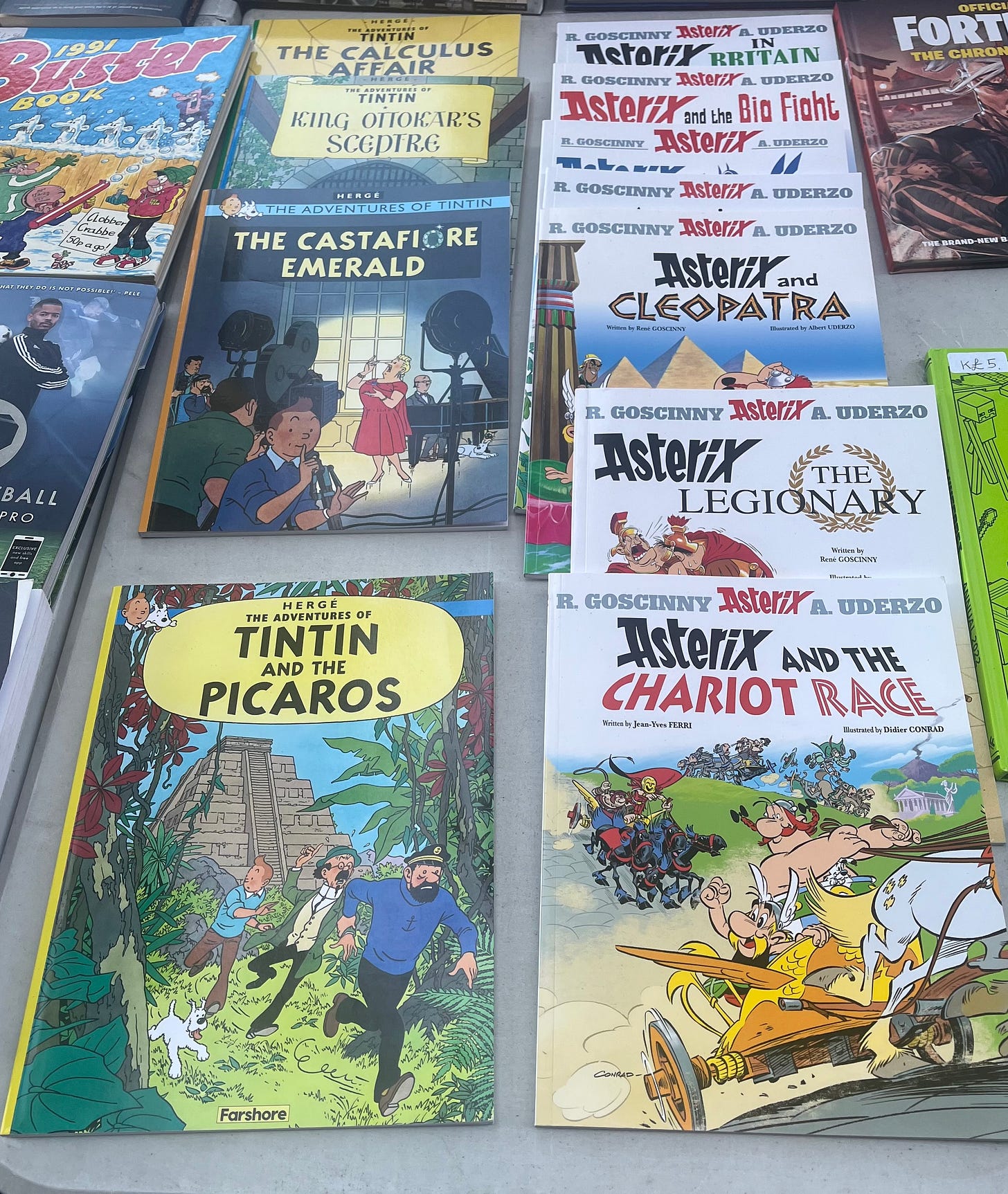

I was also charmed by this display at a Thames-side bookseller featuring two of my childhood favorites.

Who else is going to be reading Sally Rooney this week?

Thank you for reading, and I’ll see you all next time.

John

The Biblioracle

All books (with the occasional exception) linked throughout the newsletter go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and an additional reading/writing/literacy nonprofit to be determined. Affiliate income for this year is $92.10.

You remind me a bit of my first editor, Gary Fisketjon, who, when asked, “How do you know when a book is good?” said, “When I read it.”

I would quibble about "chick lit" predating "women's fiction," as to me they describe two different genres, though chick lit might be a subset of women's fiction (women's fiction, as I used it in libraries means "books that center domestic experience and the lives of women and families and usually, though not always, shy away from graphic sex and violence--thus Danielle Steel, for instance, is women's fiction, not romance). I used to dislike both terms, and I still sort of do, but I also wonder if that's a kneejerk move wherein I don't want the word "woman" appended to something because that will mean people think it's dumb, or that it should be paid less money, or that it shouldn't get to make decisions about its own healthcare. I'm not sure that's the route I want to go.