(Note: Yet again, I have yammered beyond the length of most email clients. To see the whole post, please click through to the version online.)

While I am no one’s idea of a big name headliner, I’ve often argued (tongue only partially in cheek) that rather than bringing in prizewinning and best-selling authors to talk to creative writing graduate students as masters in fine arts (MFA) programs often do, they should should instead have me stop by to drop a little wisdom.

I mean, what kind of advice does a National Book Award winning author have for students beyond write a really good book and win that year’s major book prize lottery? There is no part of that trajectory that can be gamed out or planned for. That kind of occurrence is literally a lightning strike. Sure, you can maybe increase your odds by writing a book that is the equivalent of a long metal rod that you then carry out to a field as you listen for approaching thunder, but still, the odds are overwhelmingly against such a thing happening.

I, on the other hand, can offer a lot of practical advice to people who say they would like to spend their lives writing.

For example, I am a failed novelist and academic. My novel stiffed almost entirely, sales-wise, and has been out of print for years. When I applied for a tenure track position at the college where I’d been visiting faculty for six years, I was not chosen, literally rejected by my closest colleagues in favor of another candidate.1

I will not lie, both of these things were painful, and there’s probably another baker’s dozen of various blows along the way that rocked me pretty good,2 but in the immortal words of Elton John:

These experiences taught me something I think writers should internalize if they want to be able to maintain the emotional equilibrium that will allow them to spend their lifetimes writing. (Maybe it’s good advice for anybody.)

Two propositions that seem contradictory, but aren’t.

In your life as a writer, it is likely you will deserve much more attention, success, and money than you will ever receive.

If you do not get the attention, success, and money you deserve, it’s not because someone (or someones) else has it out for you.

I thought of these things when I read a controversial interview of the writer Alex Perez by Elizabeth Ellen at the website for Hobart, an independent journal and book publisher.

There were several parts of the interview that raised ire, but this exchange was perhaps the most pointed. Ellen asked Perez about what she sees as an ideological component to what does or doesn’t get published.

Perez takes this invitation and runs with it:

The interview triggered something of a mutiny of the Hobart staff which took offense at some of what Perez had to say and resigned en masse. The incident also captured the attention of the centrist/liberal “anti-woke” crowd who decried the staff resignations as yet another example of overzealous leftists policing the expression and opinions of others.

Perez and Ellen know that his take is exaggerated (“only accepts” “every book is about”), but it’s good bait for those who want to share your anti-woke grievances, as well as good bait to raise the ire of the people Perez opposes, in this case represented by the editorial staff of Hobart.

I mean, what he has to say is obviously untrue.

For example, just last month I read Groundskeeping by Lee Cole, like Perez a graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop which is about a young writer not in Brooklyn, but Kentucky, where he is working as a maintenance person at the local college and taking a graduate course while trying to figure out this writing thing. The narrator’s sensibilities are liberal, but his background is working class and there are numerous Trump-voting characters in the novel who are portrayed sympathetically and with nuance.

In fact, it is the narrator who engages in a number of selfish acts, puncturing his liberal piety, rather than championing him as a hero worthy of emulation. While the book mines the clash of political beliefs for tension, it’s very purpose seems to be to reveal something underneath those tensions without falling back on simplified ideologies.

There’s nothing in the interview that I personally think should be verboten. The man’s entitled to his opinions, even if those opinions are “tedious” as Jonny Diamond called it at LitHub, which is quite close to my sentiment. When I saw it several days after it roiled writer Twitter, I mostly just rolled by eyes.

Whatever, I’m treading close to turning this into an “anti-anti-woke” piece, and that’s not what I came here to say.

Deciding that you are going to pursue writing as a career or avocation is a foolhardy thing that thousands of (mostly young) people still decide to do anyway. I was one of them in 1994 when I applied to a small handful of graduate programs in creative writing (including the Iowa Writer’s Workshop), ultimately gaining admission to only one, McNeese State University in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

At the time I was accepted, as they say in poker, I was pot committed, beyond ready to leave my job as a paralegal at a large law firm in Chicago, and with no alternative. The previous year I was so eager for escape I’d actually applied to become a cast member on The Real World, believe it or not.

Given those circumstances I was extraordinarily lucky to wind up where I did, in a small program where writers were quite supportive of each other, and whatever competition there might have been was not cutthroat. I do not know what Iowa is like other than by reputation, but it seems like a place where the stakes instantly seem higher, given that many writers who have gone on to considerable success have attended the program. Maybe it truly does feel like you’ve got to step on some backs on the way up the ladder.

Spending so much time immersed in a group of people that are interested in the same things you are, and want the same things you do can be incredibly nourishing. Being alone, and believing you want to write can honestly feel like a kind of madness. For sure there’s some writers who have a kind of self-belief and inner fortitude that buoys them, but the rest of us are like any other human being walking around wondering if what you think, what you believe, what you want, is ridiculous, and you are therefore a ridiculous person.

Basically, being surrounded by others who are similarly oriented makes you feel not so ridiculous.

After you stop feeling ridiculous, you may start feeling a little righteous, that you are not only not a fool, but you are perhaps superior to other people who have not had the good sense to dedicate themselves to the pursuit of art.

Some of the people you are better than may even include other writers whose work you think is not good, or who clearly do not deserve the attention or acclaim they have received. I cringe at some of the conversations I had about visiting writers to the program (including one who was just getting started at the time, but has gone on to become a widely beloved literary figure), and how I thought their work wasn’t all that great.

I mean, what did I know, other than my own desire to be recognized as good?

Hindsight reveals that this was a defense mechanism, an attempt to pump myself up against the challenges I knew were coming. It’s not like I was having great success in the writing workshop in grad school. I once unintentionally raised the ire of my colleagues by dumping all of the critiqued copies of my story they had likely spent hours working on in the wastebasket on my way out of the classroom.

They saw the act as a dismissal of their efforts and opinions, but it was entirely a product of my own self-loathing, not wanting to be confronted with what surely was a failure, based on the class discussion I’d just experienced.

It is very hard to balance the desire for attention and approval with the necessity of ignoring the opinions of the world around you so you can sit down and do something as foolish as write.

I was not alone in wondering if this thing I was spending all my time and emotional effort on was a waste of everyone’s time.

While I was in graduate school, at Harper’s Jonathan Franzen published what has become a landmark essay, “Perchance to Dream: In the Age of Images, a Reason to Write Novels.” This is Franzen when he was a mostly-failed novelist of two interesting, but poor selling novels, Strong Motion and The Twenty-Seventh City. The essay is long and ranging, and reads like a simultaneous lament and self pep talk as Franzen attempts to bolster himself and the world against the indifference that seems to attach to that which he finds so meaningful, writing and reading novels.

The essay traces the diminished place of the serious novel in American culture, having been supplanted by movies and television, and in publishing, best sellers which are indistinguishable from movies and television in terms of the experience they deliver. This was 1996, prior to the arrival of the widespread commercial internet, though Franzen has his eye on that as an additional threat even at that time.

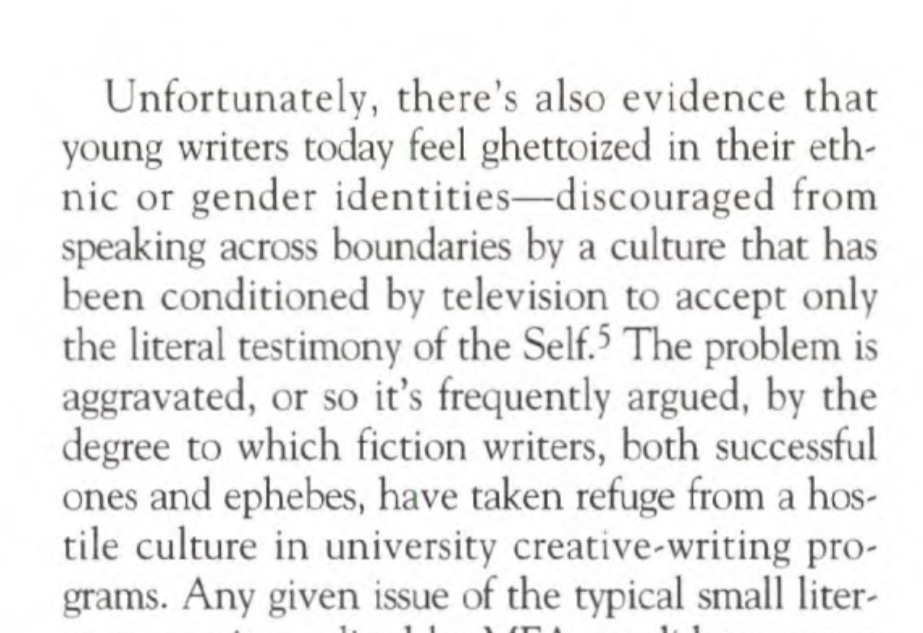

Among many threads Franzen ties together around his central theme, he includes this passage:

One can’t help but notice the similarities to what Perez has to say, that writers are primarily valued for their identities, the “literal testimony of the self.” Perez’s objection seems to be that his particular self is being denied by the people in charge of publishing.

This is a tricky thing, though. On the one hand, Perez calls on the world to reject identity as something meaningful in the expression of art, and instead focus on the universal experiences we share across the brotherhood/sisterhood of humankind. On the other, it seems pretty clear he desperately wants his identity (masculine/Cuban) to be acknowledged as worthy of representation.

Franzen identified the trend of novels of representation, particularly those by women and minority writers as a natural response to a broader culture than moves too fast for novelists to capture it.

Perez and Ellen see what Franzen identifies as a naturally occurring phenomenon as instead a conspiracy.

I have no doubt that Perez and Ellen are sincere in their beliefs that the cultural gatekeepers are acting out of ideological motives, almost as a kind of revenge against past exclusion and injustice, but that these beliefs have gone too far, that “wokeness” has run amok.

But Franzen’s analysis of publishing from 26 years ago, an analysis which also discusses publishing from 60 years ago reveals that there is nothing new about any of these tensions, that what is at work is not a cabal of woke white women in Brooklyn, but simply the forces of culture, a culture that is designed to be overwhelmingly indifferent to whatever any individual writer is up to.

As I have learned in my own career, one’s expectation should be that they will be thwarted because this is the overwhelming likelihood for everyone.

My novel did not tank, sales-wise because it is about a white guy having white guy problems. My novel tanked, sales-wise because the vast majority of novels tank.

(And in truth, I had a much better chance than many because unlike a Black writer, I wasn’t going to be subject to a coverage quota, as has been historically practiced at the New York Times.)

I didn’t fail to get a tenure-track teaching job teaching creative writing at the place I’d been successfully working for six years because I’m a middle-aged white guy - middle aged white guys are well-represented in the professorate, I promise you - but because there are literally 100s of qualified people applying for every job.

When facing this kind of disappointment, it is natural, understandable, maybe even necessary to find someone else on which you can focus your grievances, but I am here to testify that it is a dead end.

It seems clear that Perez felt and probably was out-of-step at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, and speaking as someone who would’ve been thwarted out of the gate had I not found my tribe at graduate school, I can empathize. In a way, the interview is Perez and Ellen establishing their tribe to stand against the “wokesters.”

The other tribe is resigning from Hobart in protest for platforming the anti-woke. Part of me wants to say it’s all silly, except I remember how important it was to feel less alone in the pursuit of these things that mattered (still matter) so much to me.

My advice to graduate students in creative writing as a big time failure with enough successes to keep plugging away would be to remember that the odds are never in your favor, and believing you are being thwarted by people who belong to some other tribe, as opposed to the forces that are aligned to thwart almost all of us, is not going to do you any good.3

Sometimes the impossible does happen. Adam Johnson, who has won both the Pulitzer Prize, for The Orphan Master’s Son, and the National Book Award, for Fortune Smiles, was a year ahead of me in graduate school. Adam spent his time writing and not worrying too much about who might be waiting to stifle his vision.

After writing the personal pep talk of “Perchance to Dream,” Franzen published The Corrections, a social novel that managed to capture a decent chunk of the zeitgeist for a time. Franzen catches a lot of social media flack as an avatar for a particular tribe (the entitled white man), and because he truly has a penchant for putting his foot in his mouth when he’s being interviewed. He is the subject of a 13-episode podcast series, Mr. Difficult that treats Franzen as both sublime and ridiculous, making for a very pleasurable listening experience.

For the love of all that’s holy, he ran afoul of Oprah! It would be as easy to be crushed by all this scrutiny as it is to be crushed by the overwhelming indifference of the world. But he keeps plugging away. You have to admire it. Okay, you don’t have to, but I do.

There’s really no winning. There’s only doing.

Yes, forces are aligned against you, but that’s only because they’re aligned against just about everyone.

Links

My Chicago Tribune column this week is about why I didn’t review John Irving’s The Last Chairlift.

If you’re looking for a Halloween-themed book, Parade has 34 titles to choose from.

If you’re looking for a southern book, the Southern Review of Books has the best ones for October.

Publishers Weekly has announced their best books of the year. A top-ten, plus additional lists across a dozen different categories.

Colleen Hoover’s new novel, It Starts with Us, sold 800,000 copies in its first day of release, which is absolutely incredible. Still has a ways to go to top Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, which sold over 8 million copies in its first day of release.

For your longer read of the week, “The Mystery of James Purdy” by Michael Snyder, an excerpt from his book about a writer who many revered, but is not widely remembered. I’ll be writing more about Purdy and other writers like him soon.

Recommendations

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $274.00 for the year.4

1. The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi

2. Dear Senthurian by Akwaeke Emezi

3. My Heart is a Chainsaw by Stephen Graham Jones

4. If God is a Virus by Seema Yasmin

5. Magma by Thora Hjorleifdottir

John F. - Pembroke Pines, FL

This is not a book I recommend often because not a lot of people are interested in reading a book narrated by a pretty monstrous person, but Tampa by Alissa Nutting is a wild ride that I think John will enjoy, if enjoy is the right word, which it might not be.

1. Invisible Child: Poverty, Survival & Hope in an Amercian City by Andrea Elliott

2. Homeland Elegies: A Novel by Ayad Akhtar

3. Dad's Maybe Book by Tim O'Brien

4. The White Album by Joan Didion

5. The Path to Power by Robert Caro

Sean G. - Highwood, IL

I was going to say I don’t know why this recommendation occurred to me because it’s not a well-known book and I read it twenty years ago, except that it’s a memoir about a man who finds his dream thwarted - he fails to earn tenure at an Ivy League university - and makes a radical shift in his life that finds him on the path to fulfillment: The Cliff Walk by Don J. Snyder.

I’m already looking forward to next week’s newsletter because I’m going to write more about what I cover in next week’s column, one of the best books I’ve read in a long time that I’m betting none of you have heard of before.

All best,

John

The Biblioracle

In truth, several other candidates, as I wasn’t even one of the three finalists.

One of my books went out of print literally three months after it was released. Total bomb.

Okay, there are some exceptions to this when exceptionally petty people achieve positions of influence and then wield that power in a way that advantages some and disadvantages others - I’m thinking of Pamela Paul, former New York Times Book Review editor here - but no, not all of publishing is aligned against you because they hate your ideology.

I’ll match affiliate income up to 5% of annualized revenue for the newsletter, or $500, whichever is larger.

Good advice, John, fed with an entertaining spoonful of sugar. Many of us need the "Buck up, Buttercup, you're special, but not THAT special" talk from time to time.

Solid counsel. Many thanks.