Note: This post is too long for most email clients (sorry, lots of images). To make sure you see the full text, click through to view it on the web.

I must admit to regretting declaring in last week’s newsletter that I would be exploring one of the articles I linked to, a missive from the New York Times op-ed section, “The Disappearance of Literary Men Should Worry Everyone.”

Part of the problem is that because the piece came out a week ago I have been subjected to the dreaded “discourse” about it. Fairly quickly the discourse detaches from the original text and becomes its own thing as people prosecute their particular grievances. Parsing the grievances becomes difficult because many of them find at least some purchase in the available evidence. What are you supposed to say when everyone is right, but also what they’re right about is more complicated that it’s being portrayed?

“It’s complicated” does not sell in land of discourse, which is why the ultimate reach of this newsletter is limited. But having read the piece in question, that’s what I have to say, it’s complicated. So as not to get tripped up by trying to run with the discourse, I’m going to start at the beginning.

We’ll see how far we get before I’ve tested my own spirit and the reader’s (that’s you) forbearance.

I am already squirming. The piece opens with a claim - “Over the past two decades, literary fiction has become largely a female pursuit.” - that is then followed by evidence meant to support that claim.

There are a couple of bits of evidence we can treat as facts, though they would need checking to be certain they’re accurate: 1. The Times best-seller list is three-quarters women now when it used to be half and half women and men, and 2. Women buy about 80% of the fiction sold. Let’s stipulate that both of those are accurate enough. Certainly we know that women buy the vast majority of books.

But I have some questions:

What do we mean by “literary fiction?”

Is “literary fiction” the same thing as “novels?”

Is the New York Times best-seller list a good measure for what is published as “literary fiction?”

In looking at the combined e-book and print fiction best-seller list for 12/15/24, there are between one and three books (out of fifteen) I would classify as “literary fiction,” depending on where you draw the line. Only Percival Everett’s James is indisputably literary fiction. We might also include Kristin Hannah’s The Women (though I would use an older term, “mainstream”) and even Gregory Maguire’s Wicked (which is actually a book that spawned a contemporary subgenre of its own).

But the bulk of the list is suspense, including both male and female authors (James Patterson, Janet Evanovich, David Baldacci, Freida McFadden), or romance/romantasy (Nora Roberts, Nicholas Sparks, Sarah J. Maas, Rebecca Yarros). You’ll find the same pattern week after week. Genre works dominate.

“Literary fiction” is a clear minority on the best-seller list. Some literary books break through and become significant sellers (e.g. Demon Copperhead but most make brief appearances before disappearing.

There was no work of literary fiction that got more attention than Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo, which entered the list October 13 at #2 behind Nicholas Sparks’ Counting Miracles. Both books had the same Sept. 24th publishing date.

The week of 10/20, Intermezzo dropped to #7. The week of 10/27, #10. That same week marked the 142nd week that Colleen Hoover’s It Ends With Us had appeared on the best-seller list.

Intermezzo’s last appearance on the best-seller list was the next week, 11/3, also at #10.

James, perhaps the other most talked about literary fiction of the year, has spent seven total weeks on the list. These books are fantastic-selling books…for literary fiction, but they pale next to the books that dominate the list.

Freida McFadden’s The Housemaid is #12 on the most recent list. It was published in April of 2022. Intermezzo will not return to the best seller list unless and until a film or limited series based on it is released.

The most recent available best-seller list has 7 men and 8 women.

So what are you saying, Warner?

I’m saying that the claim is followed by a series of non-sequiturs that don’t do much to illuminate the claim. The only indisputable thing we know is that women read more books than men.

Moving on:

Sixty-percent of the creative writing program applications are from women, a number which closely mirrors the overall ratio of women to men enrolled in college, a ratio which dates back to at least 2010 according to the National Center for Education Statistics. As to why fewer men pursue a degree as compared to women, we see that women have been outstripping men on academic achievement for quite some time, but also, according a Pew Research Center survey, men are more likely to say that they don’t need a degree to pursue their life and career goals.

The author doesn’t say why a 60/40 split in applications results in some cohorts being entirely female, but presuming the program admits on perceived merit, this suggests the female applicants are being judged superior.

As to “the young male novelist is a rare species,” I don’t know how to measure that. What does “young” mean? I was forty-one when I published my novel. I wouldn’t have said I was young then, but now? Whooo…

My friend Teddy Wayne is a good decade younger than me and published his first novel (Kapitoil) when he was 30, if that.

What is “rare?” How do we know the “species” when we see it? I was a young male novelist (among other things) for almost 15 years before I was a published novelist? Was I not a literary man until then?

As with the opening paragraph, I don’t know what to make of this. Without a doubt, women read more books, and more women appear to be interested in writing (literary fiction or otherwise) than men.

What are we supposed to understand about the phenomenon based on what we’re being told? I know what is being implied, that men are being disadvantaged, but the evidence presented does not make this case.

I will admit, I have heard similar tales, but this is what they are, tales, anecdotes untethered from a deeper consideration of what might be happening. I don’t think Oates was criticized because people don’t care about male writers but because what she said is probably not true.

If publishers are now rejecting works of literary fiction “no matter how good” they are indeed off the rails, but I don’t think this is happening, is it? I mean, I suppose it’s possible, but if this is happening, isn’t it much more likely a byproduct of the market for books as opposed to some kind of affirmative discrimination against young, white men because of their youngness and whiteness?

Perhaps the bar is higher for men now because the market is smaller, perhaps the fact that more women and non-white writers now have access means that books from young white men that would’ve found favor before have been pushed out as part of a zero sum game.

This gets a little complicated and sore for me because since I published The Funny Man, I’ve written a couple of other novel manuscripts that I think are quite good, publishable quality, but the publishing industry - including the people who are my professional representatives within it - say that they cannot sell them to a publisher.

Is this because I am a (no longer young) white guy? No. It’s because either, the books are not as good as I think they are, or the fact that my previous novel stiffed, sales-wise, and perhaps that I am no longer young means I am a bad bet.

I’ve made peace with that fact. It’s pretty clear that my gender and cultural station have, on balance, been far more help than hindrance. If I am occasionally overlooked now when that wouldn’t have happened before doesn’t mean I’m being discriminated against.

I would probably be more sore about this if I had never gotten my turn at the plate, so I’m not unsympathetic to the frustrations of writers who think the gatekeepers of culture have it out for them.

And for sure, I think publishers are far too focused on recreating the thing that was already successful, rather than seeking out the underserved niche. I wrote earlier this year how novel covers may be alienating male readers because of what they’re signaling.

It would be an interesting experiment to do a cover of Margo’s Got Money Troubles, a novel about a beautiful young woman who has an affair with her professor, gets pregnant and becomes and adult performer cam girl to make ends meet while being helped out by her former professional wrestler father.

Are there any other buttons we could push that might appeal to listeners of Joe Rogan’s podcast? I can’t think of any. It’s a very clever, very fun, empathetic book that any reader would enjoy, if you read literary fiction, which men mostly don’t do.

Maybe someone’s working on Manly Man Press which is going to start publishing literary fiction that would’ve made Cormac McCarthy blanch. Big picture, I think there’s probably plenty of books that are marketed primarily to male readers. James Patterson, David Baldacci, the Reacher books, Tom Clancy (despite the fact that he is very dead), tons of science fiction, are mostly read by men, the same way romantasy is mostly read by women.

I don’t think it does us much good to conflate literary fiction with all of fiction or best-seller status with quality or market pressures with aesthetic preferences. It’s a big stew of conflated and confounding shit that gets stirred up in op-eds in the New York Times, giving people with newsletters something to write about.

The latter half of the piece takes a turn that both further confuses and simultaneously clarifies things:

If you consider it for half a second, this part of the argument is a non-sequitur. The first half of the piece seems to imply that there is an active policy of exclusion going on. This suggests instead that young men have found other desired outlets. Is this exclusion driven by alienation perpetrated by literary culture standard bearers or a failure of literary culture to compete with superior pleasures?

The societal roots of these things are impossibly deep and hugely tangled, but the notion that making space for women has resulted in a regressive reactionary spike of misogyny towards women isn’t impossibly far-fetched. The fear of a Black president likely played a significant role in the rise of an overtly white supremacist one. The progress of the “me too” movement is likely a cause of Donald Trump’s turn to a presidential cabinet of sex abusers.

But what is the response, to give up on progress?

This seems unobjectionable on its face, but I also find it deeply confused. What stories are we talking about? With the Douglas Coupland reference is he thinking we need a literal Zoomer/Millennial novel by a male writer that defines the male experience and this will somehow counteract the toxic manosphere?

Here’s one:

Here’s the book’s description:

In the run-up to the 2016 election, Owen Callahan, an aspiring writer, moves back to Kentucky to live with his Trump-supporting uncle and grandfather. Eager to clean up his act after wasting time and potential in his early twenties, he takes a job as a groundskeeper at a small local college, in exchange for which he is permitted to take a writing course. Here he meets Alma Hazdic, a writer in residence who seems to have everything that Owen lacks--a prestigious position, an Ivy League education, success as a writer. They begin a secret relationship, and as they grow closer, Alma--who comes from a liberal family of Bosnian immigrants--struggles to understand Owen's fraught relationship with family and home.

Sounds like it fits the bill. This book was a Read with Jenna book club pick. It was strongly recommended to me by a young woman in her 20’s. Judging by the number of Goodreads ratings (an imperfect metric, but one that’s helpful in seeing the relative popularity of a book), it is one of the least read Read with Jenna books of the last couple years.

(For comparison, The Wedding People, also a Read with Jenna pick, has over 140,000 ratings on Goodreads. Groundskeeping has around 7500.)

I am frustrated by the original piece, and also frustrated by my own inability to come up with a clean counter to its message and claims. Yes, men are reading less and probably writing and publishing fewer books (certainly than in the past), including literary fiction. Yes, getting men interested in reading and writing literature rather than apprenticing themselves to Andrew Tate would be a good thing for both those men and society. I don’t think reading and writing has any kind of magical properties, but then again, I credit the fact that read and write as a significant contributor to my mental and emotional equanimity.

I want all the young men who have an urge to express themselves in productive ways to feel like someone is listening to them.

Maybe that’s the place to start.

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I give out my nonfiction Biblioracle Book Awards.

At Inside Higher Ed, I shared my concerns that faculty rush to embrace AI as a replacement for their own labor are hastening the disappearance of college faculty.

I really appreciated this newsletter from

on an unsettling trend in fiction, where the prose reads like the narrator is describing a television show, rather than rendering the scene using the unique tools of writing.This is cool, the

is giving away a huge collection of books in a drawing where all you need to do is give a $5 donation to this very worthwhile publisher.The New Republic has named their books of the year.

A holiday-themed classic from

by Jennie Egerdie, “Ayn Rand Writes Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer.”Recommendations

1. The End of Drum Time by Hanna Pylvainen

2. Bear by Julia Phillips

3. The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich

4. The God of the Woods by Liz Moore

5. The History of Sound by Ben Shattuck

Audra G. - Seattle WA

This looks like a job for one of the most consistently good novelists around, Jennifer Haigh, and her book, Mercy Street.1

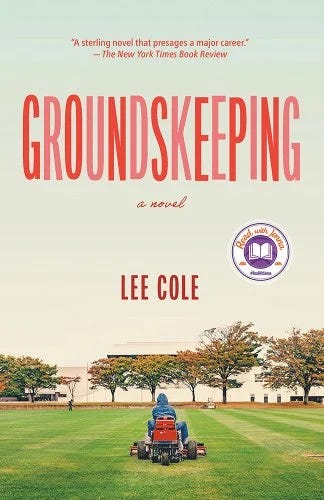

I am, as the Brits would say, chuffed over this early pre-publication review of More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI. They literally say this book is “for anyone who loves to read and write.”

Doesn’t that sound like a book you should pre-order?

Mrs. Biblioracle and I will be traveling to our ancestral home in the Midwest this coming week, and I will be doing some actual reporting for a future Chicago Tribune column. Wonders never cease.

See you next week.

JW

The Biblioracle

All books (with the occasional exception) linked throughout the newsletter go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and an additional reading/writing/literacy nonprofit to be determined. Affiliate income for this year is $161.10.

I am just frustrated with the idea that it's somehow a problem that women dominate a particular thing or field. I mean, dear God, if we let women write and read the majority of the fiction and make up the majority of most medical school classes, next thing you know women might... gasp... want to earn more money! Or, I dunno, hold more CEO positions and high elected offices.

You or one of your readers will undoubtedly know more about this, but if I recall correctly from my 19th century British novels class in college, novels were historically largely the realm of women.

I dunno. If someone can show me how getting more men to read and write novels is going to solve the wage gap or some other actual problem in the world, I'm all for it. As it is, I will just remain grouchy.

I came across this tidbit in Ron Charles's Book Club feature on the Washington Post that may interest you and your subscribers, plus you could probably flesh it out for us: Thorndike Press, publisher of large print books, will soon release a white paper documenting reading improvement in school children with access to large print books; for example, those with ADHD and those reading below grade level. The study is a joint effort with the nonprofit Project Tomorrow. (I myself am an elder and accidentally brought home a large print book from a thrift store, When I opened it up to read, something in me opened up and relaxed, and I breathed a spontaneous prayer of gratitude. I had already noticed that even normal sized print is easier to read when there is a generous space between the lines. That aspect is also touched on in the report.)