In my Chicago Tribune column this week, I try to sound the alarm about some troubling signs about the state of reading in American schools.

I am not talking about teaching phonics, the obsession of the so-called “science of reading” movement, but rather the fact that by design, fewer and fewer students will read an entire book in the course their schoolwork.

The reasons for this are rooted in the most recent round of “the reading wars” (barf), namely that the curriculum put out by educational publishers that has been embraced in the name of boosting reading scores on standardized tests is rooted in reading and responding to short excerpts, the kinds of things that are included on those tests.

I don’t really have any desire to step into the morass of the reading wars, so I’ll just lay down my cards and say that like most everyone, I believe that phonics are a necessary tool for learning to read, but at the same time, teaching phonics is not sufficient to turn students into readers.

I’ll also state that literacy tools (reading, writing, listening) are a necessity for successfully navigating American society. There is a clear economic imperative for making sure that all students achieve basic literacy.

But as Rachel Cohen writes recently at Vox, there is a significant gap between our knowledge that learning phonics is necessary for most children to be able to read and providing the curriculum, class atmosphere, and educational experiences that turn students into confident decoders - and more important to my mind - users of texts. The science of reading movement includes a strain of fanatics that seem awfully short-sighted to me, and some of that short-sightedness is going to harm students when it comes to developing these deeper relationships with books and reading.

In fact, as Cohen reports, we already have a “cautionary tale” in Great Britain, which was on the phonics-for-all train over a decade ago, and now finds itself trying to pump the brakes, having overshot the mark on phonics instruction:

To me, what’s happening with teaching reading looks very much like what has happened with teaching writing, namely that we reduce something complex, human, and necessarily messy, to something smaller, discrete and oversimplified so it can be tested and measured, in order to provide comfort that we’re making “progress.”

We are courting a phenomenon known as “Campbell’s Law,” which states, “the more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.”

In other words, when the measurement comes to stand in for the thing itself, watch out.

At my (for the moment) dormant education-related newsletter, I wrote in more detail about the problems with Campbell’s Law in education, but essentially, it leads to teaching to the test and a lack of differentiation in assessment and instruction. Anyone who believes there is a best way to reach every student on a subject has clearly never attempted the challenge of teaching.

The idea that students in Great Britain were doing daily, hour-long phonics instruction for up to three years is, to use a highly technical bit of educational jargon…nutso cuckoo.

With phonics, you only need instruction up to the point the switch flips and you can decode words, after which, you’re reading. Teaching and learning phonics is boring and repetitive, which is one of the reasons it has been resisted by some teachers who have been trained on other methods and one of the reasons why you want to move past it the moment a student is ready. Reducing reading to learning phonics for years is a surefire way to kill any engagement with and enjoyment in reading.

It also ignores that different individuals learn to read differently. Yes, phonics are a key for lots of readers, but not for every reader. Some students arrive in school already having surpassed what basic phonics instruction can do for them while others need to build knowledge from scratch. The work of teaching is the work of differentiation, and by claiming that there is a hard and fast “science” to reading loses sight of the much more complicated cultural and social dynamics around all the things we’re talking about when we say that someone can “read.”

I know plenty of literate adults who can decode words, but who also appear to be lousy readers.

If you’re looking for a deeper dive that does not rely on media hype or culture war narratives and unpacks the complexities and nuances of reading, I recommend this policy brief by my friend and professor of education at Furman University, Paul Thomas: “The Science of Reading Movement: The Never-Ending Debate and the Need for a Different Approach to Reading Instruction.”

But that’s not the main thing I came to discuss this week. I wanted to focus instead on the chief worry I discuss in my column, that students are not reading whole books as part of their school practice, and that ways this will harm their development as lifelong readers.

My motives for discussing this are multi-fold - yes, I’m intimately involved in trying to shape how we view reading and writing in our educational systems - but at this moment, I’m mostly concerned about my career as a writer and self-preservation.

In a nutshell, the only way the publishing industry is going to survive is by making more readers.

Unfortunately, we’re moving in the opposite direction.

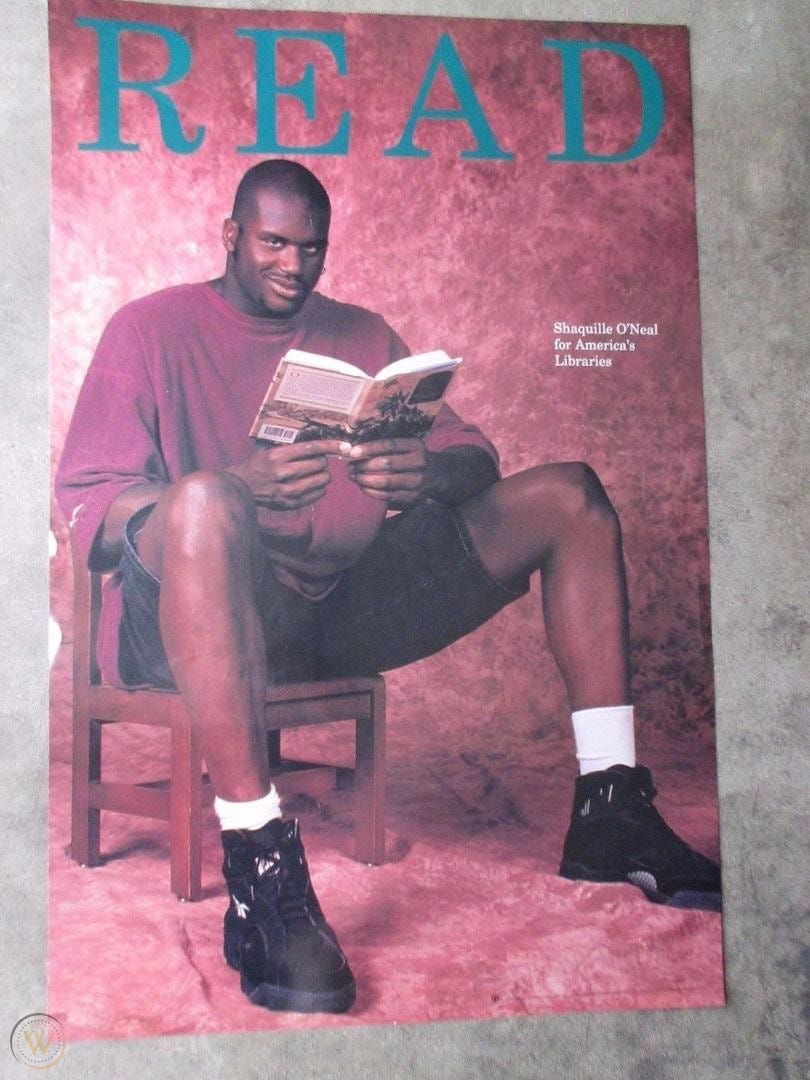

Perhaps the best known and most prominent extended campaign to champion reading is the American Library Association read program which produces posters featuring celebrities reading books. The best poster of all-time is, of course, Shaq:

There’s something about the look in Shaq’s eye that seems to say, “Hell yeah, reading, am I right?”

I remember these posters as reasonably ubiquitous back in the day, so I was a little surprised to find that the ALA continues to produce a handful every year, with 2023’s featuring Neil Gaiman, Dolly Parton, and Jason Reynolds. (You can order any poster from the ALA store.)

It’s a nice campaign as far as it goes, which probably isn’t all that far. They are primarily experienced as preaching to the choir, and while the choir deserves an uplift of their spirits as much as anyone, their souls are already captured.

We need more believers.

In terms of how to convert more to the cause, I’m at a bit of a disadvantage, having been born into the movement, and literally raised in my mom’s bookstore from the time I was a year old.

I could read before Kindergarten and thanks to going to school during the era of open education was allowed to move ahead at my own speed, outstripping the existing language arts curriculum, ultimately being allowed to craft an independent study (reading every Newbery Award winning book), and by sixth grade even spending some time helping first graders by teaching them phonics.

Point is, I needed no convincing that reading is something worth doing. How Aquaman feels about the creatures of the sea, I feel about books.

One thing I do know in general is that to move sentiment you need both good messaging and an effective medium. In terms of messaging, I’m thinking of something along the lines of: “Books are awesome.”

I mean, yes, too broad, but something must counteract the experiences young people have around reading (and writing) that signal the only reason to do this stuff is to get a good job someday, and starting with the assumption that books are awesome (because they are) may give us somewhere to go.

So here’s a couple of starting thoughts from me. They are early, perhaps provisional. If you have thoughts of your own, I strongly encourage you to share them in the comments. Perhaps we’ll get the attention of people who have the power and resources to put these ideas into action.

Education needs to include (maybe even center) reading appreciation

When I was teaching gen ed literature courses at Clemson- you know, the classes that students in non-humanities majors signed up for only because they were forced to - my primary goal was to stoke increased “appreciation” of literature. For me, that started with what students experienced as they read a book, how a book made them think and feel, and then in turn reflect on their own places in the world.

This is not a particularly academic place, but then again, my students weren’t training to be English literature academics. I tried to sneak in some of that stuff in order to help deepened their appreciation of how literature works on us. (I liked to drop Tolstoy’s quote about “art” that I wrote about previously and would often throw in bits of literary theory once they’d been switched to the on position on a book.)

I avoided trying to convince students that reading is good for you, or makes you a better person, or any other argument that suggested you should learn to read for reasons other than the inherent pleasures of the raw experience of reading, but students would glom on to those things on their own. Some of my favorite moments were seeing students truly grasp the process and meaning of subtext for perhaps the first time, and the dawning recognition that they had achieved a new power to read more closely, more acutely.

I’m actually a fan of putting “appreciation” at the center of all subjects. The motivation to do those boring phonics lessons is increased when it becomes apparent that achieving that competency opens up a world of desirable opportunities.

We’re moving in the opposite direction of this in the education system writ large. How to shift those forces is hugely complex and a subject worth for a book, not a single newsletter post, but I want to acknowledge the difficulty here. The incentives around what teachers and students are asked to do are the opposite of what they should be.

Publishers need to significantly invest in making more readers

I take it for granted that lots of (primarily though not exclusively) educated people of my generation (and older) are habitual book readers. For example, Mrs. Biblioracle, a veterinarian who barely took a humanities course after high school, reads 20-30 books a year, and reads just about every day.

The habit, once established is permanent, which is why I’m worried about a system of schooling that gives students no practice at developing this habit.

I’ve been thinking about the role publishers could and should play in making more readers after seeing a Twitter exchange between Lisa Lucas (currently publisher of Pantheon, and former director of the National Book Foundation) and

(whose newsletter I riffed on last week) discussing the apparent stasis in book publishing.The space needs innovation, which is easy to say, much tougher to do. I’m confident that it has to go beyond courting influencers on BookTok. Increasing the number of impressions a book gets is a marketing issue. The problem is that an infinite number of impressions is meaningless if there’s no underlying desire to act on those impressions. This is a grassroots problem that requires bottom-up attention.

I don’t panic about these things because I know that books are enduring, but that books will always survive in some form does not mean that we will maintain a healthy book industry which provides opportunities to those who work inside it, and interesting and desirable outputs for those who access it from the outside.

While specific innovations will be necessary, the first step is for publishers to acknowledge the problem and begin to get involved. They have reach, resources, and muscle far greater than the American Library Association, and a willing army of people (like me) ready to join the cause, but the leadership needs to come from somewhere.

Otherwise, it’s just people like me, shouting from the woods, wondering if anyone is listening.

Links

People has released their “best books of the fall” list. Getting a mention in People used to be a big deal as an indicator of a book’s potential success. I’m sure it’s still nice, but it’s not quite the same thing anymore.

I appreciated this column from Brian Merchant at the Los Angeles Times, gently correcting some assertions Stephen King made about the Luddites and their view of technology in the context of how we’re talking about AI and writing.

Bookforum is back, and this

piece on the major works of Don DeLillo’s middle period is a fantastic read.Percival Everett’s brilliant skewering of race in the publishing industry, Erasure, has been turned into a movie, American Fiction, that will be released this fall.

Kirkus has released its shortlist for the Kirkus Prize, which has categories for fiction, non-fiction and young adult literature.

Esquire has published an interesting profile of Chuck Palahniuk.

Pride and Prejudice fans will enjoy this week’s selection from McSweeney’s, “I, Kitty Bennett, Have Fallen for a Man Who Busted Out the Splits on the Dance Floor.”

On Wednesday, I published a piece on listening to a 1961 James Baldwin interview that was suddenly as current as you could imagine.

Recommendations

1. Independence by Chitra Banerjee Divakuruni

2. Impossible Things by Connie Willis

3. The Yellow Rambutan Tree Mystery by Ovidia Yu

4. An Oresteia translated by Anne Carson

5. The Bells of Old Tokyo by Anna Sherman

Jennie B. - Manchester, United Kingdom

Jennie remarked that her list is “eclectic” and boy howdy! I think Olivia Lang’s The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone will fit into her interesting array of books.1

Book Giveaway

To be eligible for this week’s book giveaway you must be a paid subscriber.

In honor of this weekend’s holiday, I’m recommending the Substack of

who is my favorite reporter commentator on American labor and has a book coming out in February, The Hammer: Power, Inequality, and the Struggle for the Soul of Labor that I’m very looking forward to.Remember to share your thoughts on how to make more readers in the comments.

See you all next week.

JW

The Biblioracle

All books linked throughout the newsletter go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and the Teacher Salary Project, which is advocating to establish a federal minimum salary for teachers of $60,000 per year. Affiliate income is $201.50 for the year.

With the disclaimers that 1) I am a librarian, though I now work for an advocacy group, not a library, and 2) that I have been a member of the American Library Association, I should like to posit that publishers do far less to promote reading than libraries do with far, far greater access to money.

To say that the publishing industry is losing money is, to begin with, a hard claim to make. Though profits have gone up and down, they are not yet in any danger of tanking: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271931/revenue-of-the-us-book-publishing-industry/. (I'm not going to provide links for everything in this post because I'd never finish it, but anyone who wants more can look around--or hit me, or your local librarian--up.)

ALA doesn't just make posters. Its Washington office regularly lobbies for increased library funding and for laws and policies that expand access to information (including books). Its Office of Intellectual Freedom has been tracking book challenges and bans for years and years--long before book bans became headline news. But more than ALA, it is state libraries and local libraries and their staff who work every day to promote, encourage, and provide books to people. Increasing numbers of libraries are going fine free (library fines are one of the chief barriers to people using libraries). Summer reading programs--held by almost every library in the country (including one in a town of 351 people where I once worked)--can seem just like chases for prizes, but they are intended to encourage reading, to help young (and old) readers find books they will enjoy, to challenge them to read something a little outside their comfort zone.

Libraries provide storytimes, often in languages other than English. They run programs for teens and kids, putting those kids and teens in a place surrounded by books chosen with their interest in mind, free for the taking. In recent years, they have been actively working to diversify their collections. They do outreach to preschools and prisons and many places in between.

The publishing industry, meanwhile, continues to consolidate and to put more and more money into the hands of already wealthy writers--a thing most writers (as you've noted) can only dream of becoming. They have rarely been friends to libraries, repeatedly trying to prevent them from using anything from microfilm to photocopying to owning ebooks as a way to squash the sharing of information and ideas, not promote it (see https://twitter.com/library_futures/status/1640428836180447232, or the paper it references if you want to read more--full disclosure, I wrote the tweets).

I believe there are good and well-intentioned people working at publishing houses and bookstores, particluarly independent presses and bookstores--but in the big picture, I see very little that publishers do that outstrips what libraries and library organizations do when it comes to encouraging reading, promoting reading, and above all making reading accessible. I have plenty of criticisms of ALA and of libraries--no institution is perfect--but not doing much to encourage reading is not one of them.

I was born in 1943 and entered first grade in an American public school shortly before my 6th birthday. We learned to read in the Dick and Jane books without sounding out any syllables or words whatsoever. Instead we learned words by sight in the same way that children learn to recognize images of distinct animals. I still remember the moment in an early grade when I came across a word 8-10 characters long that I had never encountered in print before, but I knew in a flash what it was because I had heard it in conversation at home. It would seem that building a slowly expanding vocabulary of sight words, which we read aloud in class or read silently while the teacher read them aloud, led us to absorb the principles of phonics unconsciously. Certainly the utility of words -- things as common in daily life as furniture, trees and pets -- is immediately apparent to a child learning to read, whereas hours of phonics is bo-ring -- and patronizing, frankly. I vaguely remember learning that sight reading was abandoned because of the tedium of word drills. I don't remember word drills. What I remember is learning to read as easily as slipping into water at a swimming pool: I wasn't wet, and then I was. (I understand my idyllic recounting breezes past the ignorance of dyslexia at that time.)

Another feature of my early education is that I was enveloped in my teachers' belief that I could learn (WOULD learn) and their belief that they knew how to teach me. Most articles I read about the poor reading development in children, if I can bear to read them at all anymore, reveal to me that 1) Teachers do not begin with an assumption that children can learn to read in the first place, and this lack of belief is especially apparent in classrooms of low income and non-white children; and 2) Teachers are not confident in their own teaching skills, or in the tools they were indoctrinated with when they earned their degrees in education. I routinely find myself screaming at my television , or even at bare walls in my house, in total exasperation and thereby striking momentary terror in my pets . . . Something that was once accomplished routinely in one room schoolhouses throughout the country . . . . My grandmother even taught Latin in the tiny school in the tiny town near the farm where she and her husband raised their family.

I can tell from the handful of your posts I have read that you know a lot about education, its history and the many transformations it's gone through, that you spent years as a teacher yourself, and that your passions run deep also. I would find it hard to believe that your pets, if you have any, do not experience momentary terror of their own.