Twitter tongues were wagging this week over an article in New York magazine titled, “The Fleishman Effect” by Caitlin Moscatello.

The title is referring to Fleishman Is in Trouble, the 2019 novel by Taffy Brodesser-Akner, adapted by Brodesser-Akner into a Hulu series starring Jesse Eisenberg, Claire Danes and Lizzy Caplan last year.

Fleishman Is in Trouble was one of my favorite novels of 2019. It’s the story of Toby Fleishman, married father of two, a highly regarded specialist at a New York hospital whose wife, a powerful theatrical agent, from whom he’s been separated and living apart, drops of their kids at his apartment, and disappears.

I enjoyed how the novel plays with the genre of the WMFUN (White Male F-Up Novel) first by having the wife desert the family, but more interestingly having Toby’s story being told by the character Libby, a college friend of Toby’s who is apparently fascinated by her friend’s new single male existence in contrast to what has become her staid, perhaps boring and unfulfilling, married suburban mom life.

The narrative lens makes events like Toby’s libidinous tear through young-ish middle-aged hook-up culture not so much a gross acting out by a horn dog unleashed as an object of anthropological fascination. Libby is interested in, even sometimes delighted by the way Toby’s life has been changed and complicated, a stance made even richer by the fact that Libby, along with Toby’s other college friend’s never connected with the somewhat prickly Rachel (Danes).

As the novel unfolds we get more of Rachel’s perspective, and also ultimately Lizzy’s as she more directly confronts the reason why she’s become so fascinated with Toby, her own questions about the choices she’s made in life, and whether or not she (or anyone) is happy.

Am I happy? Who is happy? What does it mean to by happy? These are all pretty timeless questions and, in my book, a solid foundation for a good novel.

I must confess that I could not get past the middle of the second episode of the television adaptation, which disappointed me given my fondness for the book. The show is well cast, and apparently features one episode with a bravura performance from Danes - which I can well believe knowing the specific source material from the book it’s based on - but the central strength of the novel, Libby’s narrative perspective, made the show unwatchable for me.

In order to recreate this perspective in the series, we get lots and lots of voiceover from Libby (as performed by Caplan), and it really started to drive me up the wall. I admit that I have a very low tolerance for voiceover to begin with, and it works well early in the first episode as Libby narrates Toby’s sexual tear over a montage of scenes, but eventually I wanted to shout at the screen, “Just shut up already, I’m trying to pay attention to what these people are doing!”

I don’t know that there was an alternative strategy in terms of the adaptation to a different medium, or rather, an alternative strategy would’ve required a radical redoing of the story, and I can understand why someone adapting their own novel would find that difficult.

But people with higher tolerances for voiceover should check the show out for themselves. It’s received many positive notices.

Right, “The Fleishman Effect.” Rachel Fleishman’s crisis/breakdown over the never ending pursuit of not necessarily more money, but more status, which can only be purchased with money, is apparently very relatable to real-life professional women with families living in New York, so we get, “The Fleishman Effect.” While a significant theme of the novel is the status/money competition among wealthy (but maybe not wealthy enough) New Yorkers, this aspect is heightened by the TV show, perhaps because the visual medium truly allows us see what this level of wealth in this milieu looks like. It’s more visceral, as embodied in Danes’s performance.

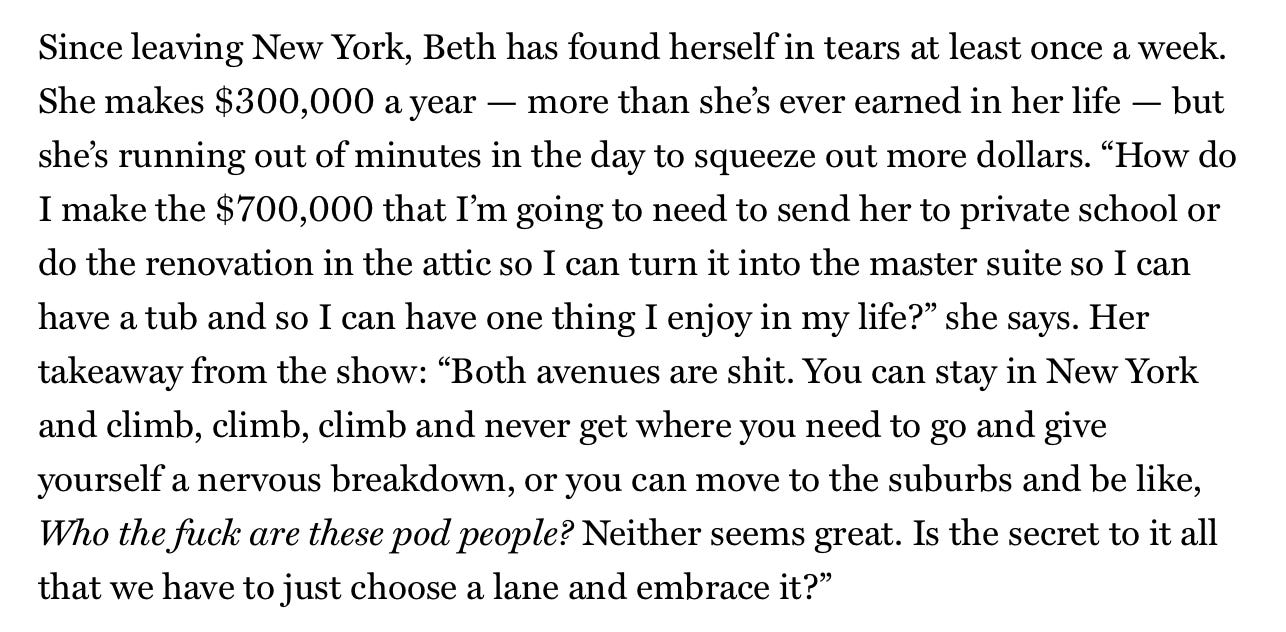

Moscatello’s article, exploring how a handful of women have identified with Rachel contains some jaw-dropping, WTF quotes, such as:

My initial response to the article, and this quote in particular, was a mix of fascination and scorn. I mean, give me a break…boo-hoo…send your kid to public school and get a grip.

Scorn and nursing a feeling of superiority is fun, for sure, but ultimately, I lean into the fascination, and make an attempt at empathy to try to understand, what the heck is going on here?

It’s not that the parents are wholly un-selfaware. They see their own actions as kind of nuts…but then do them anyway:

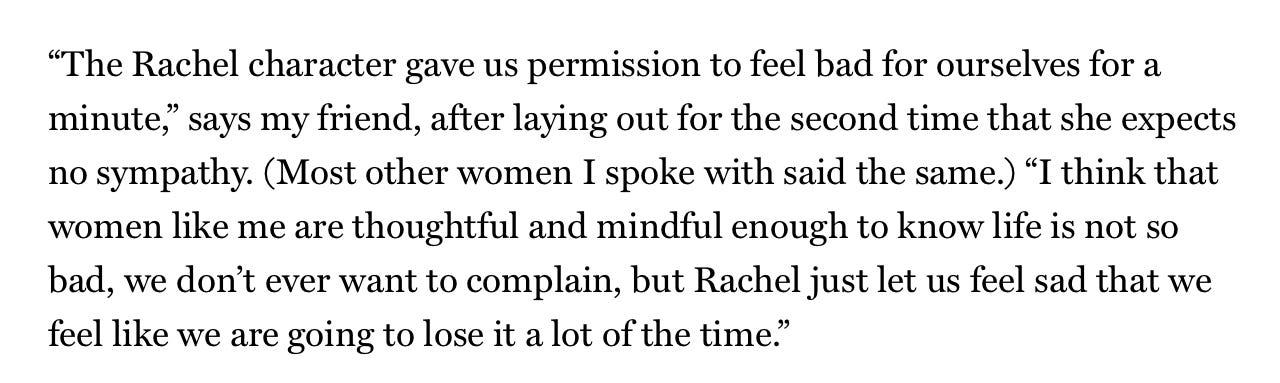

And according to Moscatello, they’re not asking for sympathy:

What becomes clear is that these women - despite their educations, their wealth, their status - in their minds they lack some essential agency over their own lives. They do not believe they have control over their own choices.

Now this interests me. What is happening in a world where people who, objectively have the resources necessary to secure a happy and meaningful existence, instead find themselves crying on a weekly basis over their lives?

I can’t say that I have a lot of answers, though I have some ideas worth considering.

At her newsletter, Culture Study,

unpacks some recent data from a very comprehensive Pew Research Center survey and finds a phenomenon of “The Anxious Style of AmericanParenting.Petersen’s post is very worth reading in full, but some of the top line findings are interesting. Parents feel stressed and anxious most of the time, and expect to feel this way, that it is a part of parenting. Women also (unsurprisingly) feel these issues more acutely than men.

But here’s the most striking finding, as it relates to “The Fleishman Effect,” lower income parents more often experience parenting as “enjoyable and rewarding” than higher income parents.

Petersen believes sociologist Annette Lareau’s concept of “concerted cultivation” explains this finding, as upper-class parents “work tirelessly to give their children the skills to reproduce their class position.”

I’ve written how these attitudes are rooted in a culture of “scarcity and precarity” where lower-class students experience actual scarcity of opportunity and resources, while upper-class students internalize a sense of “precarity” that their advantages could be lost in an instant if a single wrong move is made.

It is not only the Rachel Fleishman’s of the world who are breaking down over these things. Their children are crumbling under the stress as well, as the rise in school-related anxiety and depression continues year after year.

A huge part of my pedagogical philosophy as a writing teacher is about trying to free students from this dynamic, and doing so by giving them maximum agency (within a structured experience) over not just what they do, but how they do it, and perhaps most importantly, how they feel about it.

This is what is most striking to me about the women profiled in “The Fleishman Effect,” they don’t seem to give any importance to how they feel about the lives they’re living beyond acknowledging to themselves that they’re pretty miserable.

They are bottomless wells of wanting with little sense of what might fill them up. Sharp readers may have noticed in the graphic at the top of the page that New York categorized this article under “Rich People Stuff,” but I wonder if this is only the province of rich people.

Being in a state of wanting seems to be the American way. the Bible says that covetousness is a sin, but it we really live in a world the opposite of that. To not want is suspect.

In last week’s newsletter, I explored something I need to remind myself of sometimes, that I have control (agency) over what I pay attention to and how much time I spend paying attention to it.

The exercising of this agency is something of a skill, developed over time, and needing periodic attention to keep in working order.

What if being happy, or if not happy, content, is also a skill? It must be, right?

The women in the article are roughly 10-15 years younger than I am, late millennials who came through the culture and education system at a time that was significantly more punishing than I did. The overwhelming belief I had growing up as the child of two college-educated parents in a prosperous Chicago suburb was that I was going to be fine. I had an enormous amount of advantages of birth and material, and people born into those circumstances don’t often fall out of their social class.

And I haven’t. Not yet, anyway.

I was about to say that I’ve had the luxury of trying to orient my life towards what I’m interested in and good at, but what a weird word to use, “luxury.”

What has happened that this is now perceived as a luxury and I feel overwhelming good fortune to be in this position?

Too big a question to start to follow in what remains of my space for this week, but perhaps you all have some thoughts on the subject, and we can pick this up another time.

Links

My Chicago Tribune column this week is a lament that we continue to have a need for things like Black History Month because we do not do enough to respect Black History as American History.

Sticking with the theme of Black History Month, Nikole Hannah-Jones shares her perspective on exactly why some folks are so eager to shut off access to the The 1619 Project.

HarperCollins and the striking editorial workers reached an agreement ending their more than two-month long strike.

A re-telling of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim, written by Percival Everett? Yes, please.

Salman Rushdie, still writing, talking to the New Yorker following his near-fatal stabbing last year.

Grady Hendrix, author of the recently released How to Sell a Haunted House has his own spin on book events, and it works.

Fascinating newsletter post from looking at how writers are able to make good money changing the publishing equation by connecting not with customers, but "backers" on Kickstarter. (Thanks to Charlie Becker for the tip.)

Recommendations

All links to books from this site go to Bookshop.org, and affiliate income will be donated to Open Books of Chicago, and another book or reading-related charity to be named later. (Make a recommendation in the comments!)

1. Women Talking by Miriam Toews

2. Perpetual West by Mesha Maren

3. The Shadow King by Maaza Mengiste

4. Giles Goat-Boy by John Barth

5. The Great American Novel byPhilip Roth

Brian S.

I’m going to take advantage of Brian’s apparent interest in writers of a generation or two back and recommend one of my favorite Stanley Elkin books, The Franchiser.

That’s all for this week folks. Be on the lookout for a special midweek announcement from yours truly about what I think we should be doing about teaching writing in a world of artificial intelligence.

Take care,

John

The Biblioracle

Love these observations, I think a lot of this comes down to the overwhelming neoliberal ideology that has been dominant for many decades in the US and other parts of the world. This kind of world view sees everything as an individual problem to be solved by individuals, and by extension all failure is personal failure and all successes are personal successes. I really think this extends to parenting where people tend to attribute the success/failure of children to the parents. This would seem paradoxical if you view children as individuals responsible for their own successes, but I think many people don't recognize children as individual human beings with their own wants, needs, and personalities. I can't remember if you used the term "neoliberal epistemology" in a different blog post, but I've been thinking about that a lot. How we have a flood of information on the internet and we expect each individual to arbitrate that information and make their decisions. I feel like parenting is probably the best example of this, even pre-internet as new parents were inundated with thousands of contradictory books on parenting styles. I disagree with a lot of what Pinker says in The Blank Slate, especially how he frames his arguments, I view his style as much more of a debater than an enlightener (loved that piece too, by the way), and I think his framing often obscures more nuanced arguments, but I think he was right in pointing out the individuality of children and the fact that much of what they learn is from their peers and social relationships, and parenting styles (within reasonable bounds) don't have as much of an effect as parenting books would suggest. Finally, I think many adults don't give children and young people enough agency to make their own decisions and learn from their own mistakes and triumphs and this may affect people as they become adults and are afraid to take agency and act outside of what they believe is acceptable in their social circle.

I feel exactly the same way about the Hulu adaptation, except I did t make it past the first episode. A pity considering the excellent source material.

As for charity suggestions, you can’t beat Reading Partners in my book: https://readingpartners.org/