I’ve been thinking about “engagement” this week.

If you want to have any success as a writer, you must engage your audience. The people who read this newsletter know what I’m talking about, that sensation of slipping into what feels, not like a one-way conversation, but a mutual exchange between you and the authorial intelligence.

There’s a George Saunders quote that I copied from an old Salon Table Talk forum over 20 years ago that I used to put on my syllabus when I would teach undergraduate creative writing. The syllabus was structured as a “Frequently Asked Questions” document where I tried to anticipate the kinds of things students were wondering about at the start of the course, and I used the Saunders quote to introduce one of the semester-long questions we’d be grappling with.

I told students that a writing course should be viewed as “a shared inquiry into the subject at hand,” meaning that students were as or more responsible for doing the heavy lifting of figuring stuff out as I was. My role as the instructor was to provide the necessary structure and guidance for the inquiry to be fruitful, but I would not be riding herd over their learning. The goal was to figure out some of this stuff for themselves.

My belief and my experience is that this is a far superior route to fostering student engagement than relying on test and punish policies or other techniques primarily rooted in external motivation. It also helps them learn more, though that learning can be unpredictable (a feature, not a bug).

I sometimes forget that this philosophy is out of step with what a lot of people believe school is, or should be like. I was reminded of this a couple of weeks ago when I was asked to come on to the WGN Chicago morning news and talk about the implications (what they call the “dangers”) of the ChatGPT algorithm, and the conversation I wanted to have (Hey, let’s make writing worth doing!) and the conversation the anchors wanted to have (Shouldn’t we just expel a couple of kids as an example so they won’t use it to cheat?) were clearly at odds.

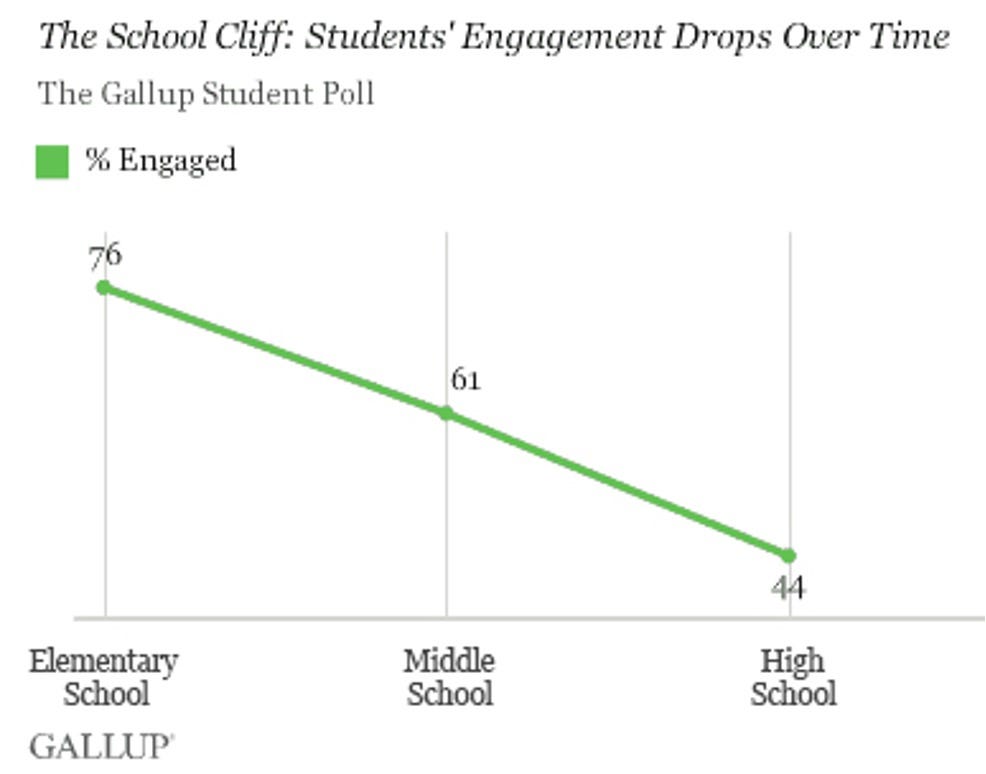

There is a well-established “engagement crisis” in our schools. Every year of additional schooling makes students progressively less engaged, until by the end of high school, more students are either not engaged or worse, “actively disengaged” than are actively engaged.

That data is pre-pandemic, so we can only imagine how dire it looks now.

My belief is that this disengagement is rooted in the kinds of things we ask students to do in school, and then how we judge what they do, and that we should spend much more time considering how to get students engaged in learning, and much less time sorting and ranking students according to some pretty dubious measurements.

Without engagement, everything else we say we want students to do and learn simply becomes much harder. I want those things to be easier.

Engagement is also the be all and end all of writing online, at least if your goal is to make some $’s in the process.

I often wrestle with how I want to engage readers here and in the other places I publish, and often my core values about how I want to engage with readers, and the kind of engagement that leads to attention (and therefore $’s) are often at odds.

My goal is for my writing to engage readers on a “shared inquiry” level, where whatever I am saying is not viewed as a declaration that demands agreement, but an exploration attempting to illuminate the subject at hand in a way that encourages the reader to go exploring with a light of their own. I won’t claim that I always succeed, and I’m going to close this newsletter with some recommended books from writers that I think are surpassingly good at it whose abilities I can only marvel at, but I’ve gotten some reader feedback recently that makes me feel like I’m on the right path.

A few weeks ago, one reader sent me a short email saying, essentially, I like reading your column, even though I don’t always agree with you. Be still my heart! This is the kind of response I most treasure.

Even better, this past week I had a long, cogent, and thoughtful pushback argument on last week’s newsletter about Pamela Paul’s American Dirt op-ed. The reader apologized for sending it, but did so anyway because they felt compelled to respond directly.

No apology necessary! I love that shit! The reader and I exchanged several emails over the course of the week, and I don’t know that either of us convinced the other to change their core position, but I know that I understood the nature of the reader’s objections to my argument much better at the end.

Win-win. So much winning.

Agreement is fundamentally boring, and writing like Paul’s that demands agreement by failing to be sufficiently transparent, that does not seem to invite direct response, and is instead designed to provoke outrage is - in my view - an ethical breach with the audience.

Still, the reason I wrestle with how to engage readers is because Paul’s method is far far better at generating attention. Her column spawned at least half-a-dozen newsletters (like mine) to respond. Sure, most of them were calling her out for the terrible inconsistencies of her argument and crappy analysis, but attention is attention in whatever form it takes.

At

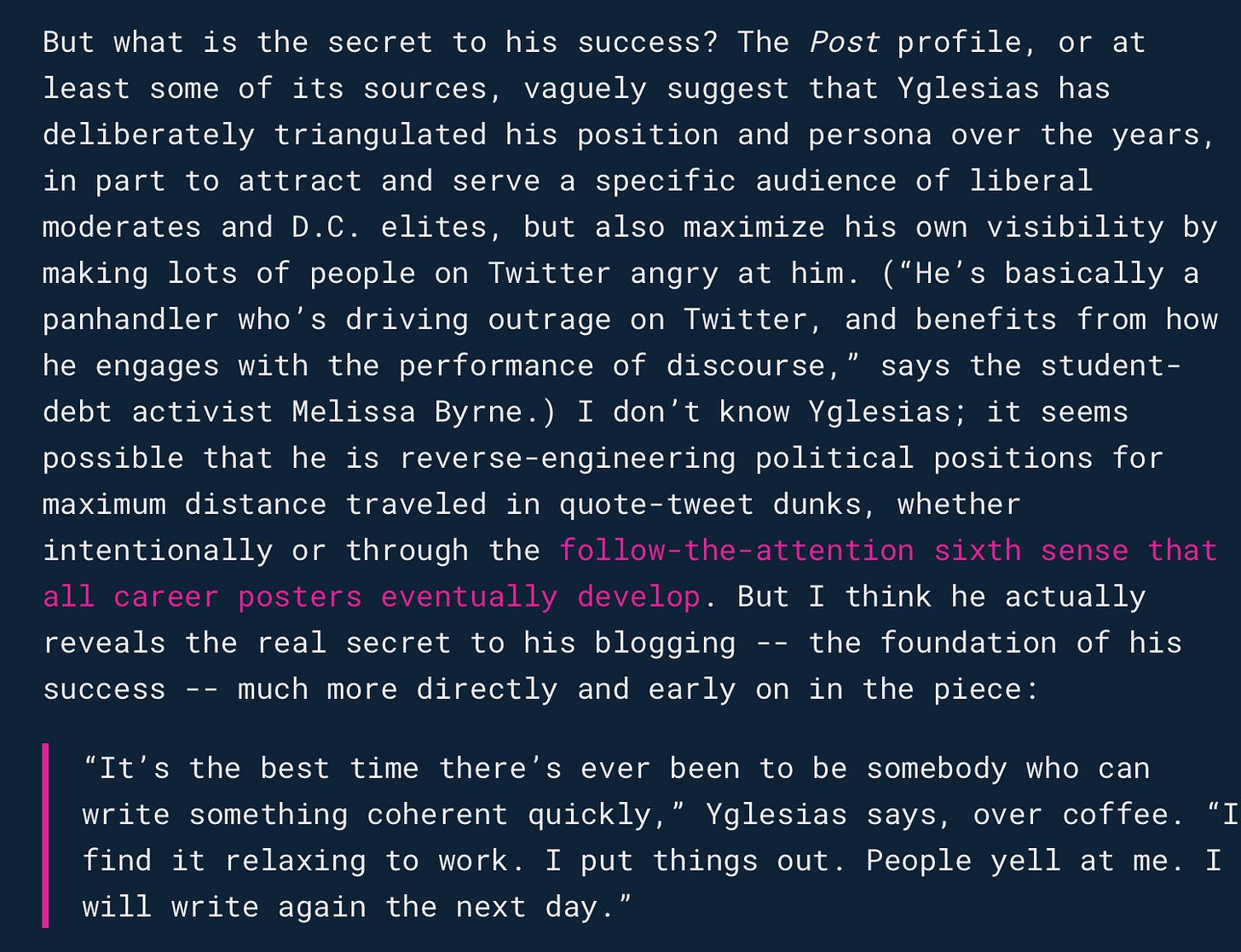

Max Read nails this dynamic in his analysis of the extreme popularity of longtime blogger and current Substacker, Matthew Yglesias, quoting Yglesias from a Washington Post profile of him from a few weeks back.“I put things out. People yell at me,” Yglesias says, summing up his modus operandi.

I wish I could describe how cynical I find this, and how depressed it makes me. The chief source of my depression is because it obviously works, and has indeed worked on me, as I’ve felt compelled to respond to some completely wrong thing Yglesias said about education multiple times, and each time, even though I’ve convinced myself I’m doing god’s work by countering bad information or analysis, even if that’s true, I am also elevating Yglesias in the process.

It works great for him because his world view is essentially as a pro-status quo left-moderate, a stance which a huge proportion of the audience who read online newsletters and have the money to subscribe already hold. I find him often infuriating, even when I agree with him. His audience finds him correct, and reassuring.

Both camps bring him attention, and then even more attention when they go online and yell at each other on Twitter about something Yglesias said.

Good work if you can get it, and if you can do it. Yglesias makes somewhere in the high-six to low-seven figures on his Substack newsletter alone. I’m hoping to get to $20k by the end of 2023.

Unfortunately, I can’t seem to do it. For one, I do not want to write things for the explicit purpose of some proportion of the audience to yell at me. For two, I cannot write four or five of these pieces a week as Yglesias manages. In order to engender the kind of engagement with the act of writing that I find fulfilling, and that I believe leads to the kind of audience engagement I’m looking for, I must spend many hours during the week ruminating over what I am going to write and then half a day or more pulling these thoughts together into this space.

Don’t get me wrong. I love this. As I type, it is 10:30 Saturday morning, I am in a lounge chair up in my wife’s office, which is the sunniest spot in the house at the moment. One dog is nestled next to me, the other is spilled out of his bed nearby:

Thinking about this life that I get to live filled me with a sudden wave of contentment. Sometimes when I tell people that I work every day (which I do), they look at me with pity, but in this moment, I am doing exactly what I want to do.

Would Matthew Yglesias-level Substack revenue make this work easier? Maybe, in the sense that I could get by with fewer balls in the air simultaneously. Would it make it more fulfilling, more interesting? Almost certainly not. In fact, it’s probably closer to the opposite.

When I manage to work myself up about something someone else writes on the internet, or puts in Twitter, I try to remind myself that I have agency over my own attention, my own engagement. For a while, as the central subject of today’s newsletter, I was thinking about capitalizing on a semi-viral tweet of my own about how The Atlantic uses headlines meant to provoke a certain type of reader into negative engagement (I put things out. People yell at me.), but the headlines unfortunately allow too much space for readers to misconstrue the message of the piece.

There’s lots of people like me who are frustrated by this and some of the content The Atlantic puts into the world, and the way they stoke engagement online, and I know that I could rally those folks around me as part of a cause. (It’s why the Tweet did much more traffic than the usual for me.)

But the more I thought about it, the more I didn’t want to write that newsletter. It wasn’t interesting to me. Some of the reply tweets to my tweet agreeing with me bothered me because they’d taken my point - that I want headlines that interest and inform, rather than merely provoke - and dragged in a whole host of other complaints that I mostly agree with, but also aren’t what I was talking about.

Pamela Paul also wrote another terrible column this week. But I’m not going to link to that or comment further either because I’m tired of handing over so much of my attention to that stuff.

What I am going to do, is highlight a few books of essays that I think do the job of stoking the kind of engagement I particularly value, writers that in Saunders’ formulation, make the reader and writer smarter together than either one could be individually.

I sometimes break writers down into broad categories: Illuminators v. Debaters v. Flamethrowers.

It’s rare that I have all that much interest in a pure flamethrower, certainly not at book length. One flamethrower I did enjoy and miss to this day is Molly Ivins, who was great because she was so funny, and even as she hurled fireballs, she was pretty good at illuminating.

Debaters are my least favorite category. A debater is more interested in winning an argument than illuminating a subject. They will ignore contrary evidence, or boil retreat on a particular point until they find the last defensible shred. They are legion on Twitter, Yglesias himself is about 85% debater with 15% illuminator, and I think the proper proportion of those traits is those numbers reversed.

An illuminator is someone who ideally leaves their audience smarter about the subject at hand than they were before, while also leaving room for disagreement and additional avenues of exploration. The best compliment I can give a writers is that after reading their work, I want to think more about their subject.

All of the writers I’m about to share are first-class illuminators.

At the top of any list like this is Tressie McMillan Cottom, herself a New York Times columnist, and really working unlike any other of their contributors to that space in terms of the way she engages in intersectional analysis and deep storytelling. Her collection, Thick, is her at her best.

I do not always agree with Wendell Berry. I often don’t agree with Wendell Berry, but I cannot deny the way he forces me to grapple with the subjects - the environment, modern life, sustainability - in a way that makes me question my own assumptions and confront whether or not I’m living close to my values. The World-Ending Fire is a great compendium of his work.

Over the last several years, I’ve missed Coates’ voice, but that a writer of his accomplishments has chosen to go publicly quiet in order to concentrate on the work that moves him is a testament to why his work holds up so well. He will absolutely provoke the reader, but in a way that invites engagement, rather than - I put things out. People yell at me. We Were Eight Years in Power is a collection of his greatest hits of the Obama era.

I am not a person of faith, and yet I love reading Marilynne Robinson’s exploration of faith because they help me be more thoughtful about what I do believe about the world, and why. What Are We Doing Here? Is grounded in a particular, Trump-era, moment, but also has a certain timelessness.

The reason I have failed to get the next installment of “A Book I Wish More People Knew About It” into the system and out to your inboxes is because it was written by my friend John Griswold and I’ve been looking, and not finding the time to write the kind of introduction he deserves. John is one of the great illuminators of our age, and not enough people know his work. The Age of Clear Profit is his second collection of essays that explores the societal forces that threaten to tear us apart, and what it might take to knit ourselves back together, both individually, and collectively.

I have six or seven other authors that come to mind, but I’m going to stop there and ask the readers. Who do you go to when you look for illumination?

Links

My Chicago Tribune column from two weeks ago got into my archives. It’s an appreciation of the work that the striking workers at HarperCollins do and an attempt to at least acknowledge their importance.

This week’s Chicago Tribune column was a topic suggested by Mrs. Biblioracle, a consideration of the pleasure of being read aloud to by another person in the room

Anyone who thinks we’re going to be able to detect and punish use of ChatGPT by students by, for example, making students handwrite their work. Should check out this video. As I said previously, “ChatGPT Can’t Kill Anything Worth Preserving.” Let students do the writing that’s truly engaging.

Over at Ms. Magazine, a February list of books being published by “historically excluded groups.”

Florida teachers are removing books from their classroom libraries or concealing them behind paper lest they run the risk of being charged with a felony.

The New York Times is recommending nine new books this week.

Carin Goldberg, a book and album cover designer passed away recently. An interesting career consideration of someone who’s work everyone reading this at this moment has likely seen, but didn’t know the artist behind it.

Recommendations

All links to books from this site go to Bookshop.org, and affiliate income will be donated to Open Books of Chicago, and another book or reading-related charity to be named later. (Make a recommendation in the comments!) I’ll also match the affiliate income with a donation of my own up to 5% of annualized revenue or $500, whichever is larger. Affiliate income is up to $29.30 for the year. Not bad for one month in.

1. Amos Berry by Allan Seager

2. Gods of the Upper Air by Charles King

3. Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel

4. All My Mother's Lovers by Ilana Masad

5. House on Endless Waters by Emuna Elon.

Sue R. - Wilmette, IL

Very exciting to see my good old Uncle Allan Seager on the list, as well as Ilana Masad, a 2014 winner of the McSweeney’s Column Contest for her series, “Not So Timeless After All” in which she wrote funny and charming obituaries for well known characters from children’s books, including the first installment on “Pooh, Winnie The.”

Right, a recommendation. How about Mrs. Fletcher by Tom Perrotta.

1. Sea of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel

2. Building a Second Brain by Tiago Forte

3. Liberation Day by George Saunders

4. A Rule Against Murder by Louise Penny

5. How to Live: A Life of Montaigne by Sarah Bakewell.

David P. - Bloomington, IN

Montaigne…there’s a cat that specialized in illumination. My Biblioracle book club just read Evan Connell’s Mrs. Bridge, and it reminded me how everyone should read this book, so that’s what I’m recommending to David, and everyone else.

A couple of recommendation requests in the queue still that I’ll probably make use of when I draft my next Tribune column, so the wait still isn’t too too long. Check out the method for requesting a reading recommendation at that link above.

Apparently there’s supposed to be six more weeks of winter, and some of you may be feeling that extra hard right now.

Stay warm, read a book. Maybe even read a book to someone else.

Take care,

John

The Biblioracle

Thanks John. Your framing of flamethrower, debater, and illuminator also resonates in my circles which are much more focused on technical writing as an engineer.

Unfortunately, most students seem to think that “technical” = “boring.” While there are certainly different norms, many of them approach the communication from a debater framework and intentionally craft the story to make their points and minimize any weaknesses. I find it hard to believe this isn’t correlated with the reproducibility crisis in science. And also know that the debater framing is at the root of a lot of the reports and presentations I see.

Looking forward to sharing this framework with my students to help them see the coherence between their various writing venues and audiences.

I’m on bookstagram, and I always try to spark conversation with my posts. The only ones that ever get a lot of comments are the very spicy negative reviews, or questions about personal preference. The ones that follow deeper reviews or require thinking, 🦗. But then the Substack I comment most on? The Unpublishable, about dismantling beauty culture - EXTREMELY personal!! Human nature I guess? 🙃