If I know I’m going to read a book, I never ever never read any reviews ahead of time. Like Jennifer Egan’s forthcoming The Candy House, billed as a sequel to A Visit from the Goon Squad, I don’t care what anyone says about that book, I’m reading it right when it comes out.

This is not arrogance or a belief in my own infallible good taste, but more like the opposite, a recognition that I’m actually pretty easily influenced by pre-experience information that may color my response, or even dissuade me from reading a book where I might be on the fence.

This happened to me recently with the novel Vladimir by Julia May Jonas, which has gotten a significant promotional push from the publisher, a push which managed to hook me, leading me to throw my copy into my bag for Mrs. Biblioracle’s and my recent vacation.

Then, in the midst of the vacation, literally the day before I was going to finish one book and be ready to start another, I read this mixed review in the New York Times. When I opened Vladimir to start it, I was convinced within a few pages that I was being underwhelmed, and put the book aside for a different choice.1

Deep down, I wonder if I gave the book a fair shake, particularly after reading another review of the book, this time in the New York Times Book Review2, that is so positive it seemed like it could’ve been written by the publicity person who pitched the booked to me originally. What if I’m missing out?

I mean the description of Vladimir makes it sound pretty up my alley:

So I’m going to give the book another, hopefully fairer shot at some point, but it was a good reminder to me that in situations where I do not have any background that allows me to ground my opinion against someone else’s, I can be pretty impressionable.

Now, once I’ve read a book I always have pretty firm, pretty definite opinions that are unlikely to be shaken by someone else. I’m always open to the possibility that others can have a different experiences with a book than me, but I’m not about to substitute their judgement for my own.

I know what happened to me as I read a book.

Of course, sometimes we have to outsource our judgements to others because we have neither the time nor expertise to form our own.

And sometimes it’s just nice to take a break from the mental tax of making choices.

The vacation Mrs. Biblioracle and I took recently was with an active tour company we’ve traveled with seven or eight times now, and the chief pleasure of the whole experience is that none of it requires us to make any judgements. What we see, what we do, where we eat, when you wake up in the morning is all decided for us by experts who have scoured the region looking for the best possible experiences, and made an itinerary meant to maximize the traveler’s pleasure.

Not having to make choices is truly blissful, and the re-entry into regular life after one of these trips makes me feel like a failure as an adult since everyday actions - like deciding what to eat for dinner - seem genuinely burdensome for a day or two.

That fades soon enough, but I find myself longing to be released from the burden of making judgements because those choices can be difficult and fraught and of course you sometimes have to pay the consequences of your own bad choices.

Wouldn’t it be great to just outsource all the choices I have to make to someone who is smarter and better informed than me?

I’m confident folks who turn to a guy and ask him what they should read next based on the last five books they read can appreciate the pleasure of outsourcing your judgement.

There is no more difficult or fraught subject on which we have to exercise our judgement than the Covid pandemic. The individual calculus of how to live through this thing is ever-present and just plain wearying. I’d like to think that I’m a sound thinker, capable of weighing information and evidence, but the ground seems to constantly shift beneath us, making a choice that seems reasonable one-week, foolish in another.

“Do your research,” has become the rallying cry of covid-deniers and anti-vaxers pointing toward nonsense as justification for their points of view, but unless you’re willing to simply outsource your judgement to someone else, you kind of have to do your research.

This is not to say that you’re likely to figure any of this stuff out definitively - you make the best call you can based on your own needs and ethical/moral frameworks - but I tend to believe that informed judgment is better than not, and of course where you get your information is really important.

This is why I am so consistently frustrated by the work of David Leonhardt, the man in charge of The Morning at the New York York Times, which is one of the most influential sources of information about the pandemic, particularly for those of use who like to believe we’re in the reality-based community.

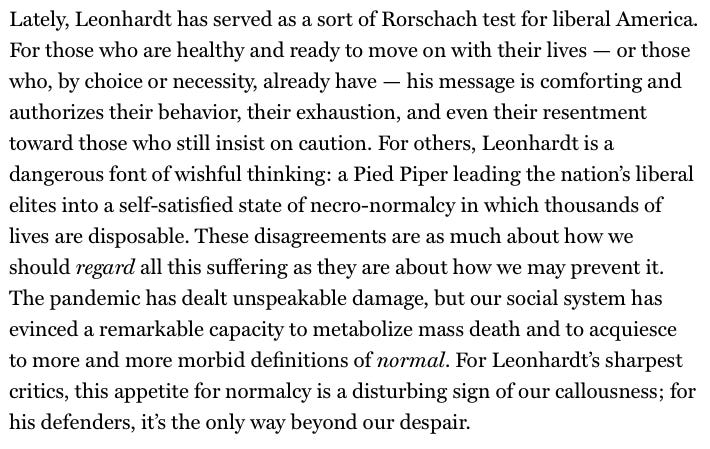

In fact, Leonhardt was recently profiled as “the pandemic interpreter,” at New York magazine by Sam Adler-Bell, and in a testament to Adler-Bell’s effort, those of us who are critical of Leonhardt think it was far to soft, while his supporters think it was a hatchet job.

I think that the fact that Leonhardt has become a pandemic interpreter speaks to both our collective need to understand what the heck is going on, and the cultural influence of the New York Times on people like me, the folks who also listen to NPR, are likely to say that Wilco is one of their favorite bands, and who get misty-eyed when they see pictures of Barack and Michelle Obama.

Leonhardt’s schtick is to offer data-informed opinions about the pandemic. Unfortunately, he is either miserable at working with and interpreting data, or rather than letting the data tell a complex and nuanced story (as data usually does)3, he cherrypicks numbers that support the angle he wants to promote.

I won’t repeat all of what I wrote elsewhere about a recent Leonhardt column that essentially declared the pandemic over (even as more than 2000 people a day were dying), in which he argued that anyone who was young, and/or vaccinated and was still worried about getting sick with Covid was acting irrationally.

Leonhardt chalks this up to “political ideology,” arguing that caution over Covid has become a point of identity and badge of honor among liberals, leading them to excessive caution in response to folks on the right.

It’s certainly a possible interpretation, but it’s hardly a plausible one. Leonhardt abuses several fundamental principles of working with data to come to it.

One is this conflation of correlation with causation. Yes, people who identify as politically liberal are more likely to be cautious about Covid, but that does not mean their caution is rooted in political opposition to those who are less cautious.

Second, he equates “worry” with worry about dying from Covid, but this is not the only reason to be worried. For people who are not economically secure, or who don’t have sick leave, or cannot afford to be off work for even a few days, a sickness that knocks them out for a week could be a significant setback.4

Other people may anticipate things like vacations or family gatherings or weddings and be worried that getting sick may disrupt those occasions.

There are some interesting questions underlying the fact that people who are at relatively low risk from the worst outcomes of Covid are still cautious, but Leonhardt chooses not to go there. The worst part for me is that he likely had (or could have collected) data available in the survey he commissioned around income, personal savings, insurance access, sick leave, etc that would’ve added nuance to our understanding of these attitudes, but he chose either not to collect or not to share that data.

I find it frustrating because this is a person with a very influential platform who could be doing a better job at informing the public so they can make sound judgements, who is instead (IMO), using that platform in a way that substitutes his judgement for others’.

Of course, as I’m doing here, we have the freedom to reject or challenge anyone’s conclusions, outsourcing one’s judgement on what we should be doing about the pandemic is sorely tempting (to me at least), and I think Leonhardt abuses his position on that front, presenting himself as a neutral arbitrator of data, rather than being transparent about his own stance on these issues.5

I’m not alone in this belief, and Adler-Bell quotes a number of Leonhardt critics with far superior credentials to mine with even harsher things to say.

But ultimately, this is not just a disagreement about how we interpret data, or which data is meaningful. It’s a test of our individual world views, how we orient our individual moral and ethical choices when we’re up against a collective problem. I thought Adler-Bell captured the dynamic well.

I will admit that a fair portion of my ire is the eagerness with which Leonhardt embraces a return to the pre-pandemic status quo as a desirable goal, mostly because I had a lot of trouble with the pre-pandemic status quo, as reflected in my books about the structural impediments to helping students learn to write, and the messed up structures that govern our system of post-secondary higher education.

I think we’ve been under reacting to significant social problems and inequality for the entirety of my lifetime, and it bums me out to see the speed and eagerness with which some people want to return to that status quo, provided they get everything they need.

I honestly don’t know how I got here. Oh, right…judgement.

What to say? It’s complicated. I try my best to be transparent and trustworthy - Leonhardt would claim the same, I’m certain - and no one should substitute my judgement about Covid, David Leonhardt, books, or anything else for their own.

There’s lots of people and sources I trust, so I’m not advocating for a kind of “nothing matters, it’s all the same” ethos.

In fact, everything matters. That’s why all of this seems so hard sometimes.

Links

My Chicago Tribune column this week is a tribute to an 8-year-old who decided he wanted to write a book, and an encouragement to others who think they might want to write a book.

The New York Times recommends nine new books.

Teen Vogue has “25 Books by Black Authors We Can’t Wait to Read in 2022.”

At The Atlantic, Hannah Giorgis has “Eight Books That Reevaluate American History” by looking at previously uncovered contributions and involvements by African Americans.

Adrienne Westenfeld, writing at Esquire, rounds up “The Best Nonfiction Books of 2022 (So Far).”

The J. Anthony Lukas Prizes for Excellence in Nonfiction has announced their shortlist of nominees, while the Los Angeles Times has announced the finalists for their prizes.

Recommendations

All books linked below and above are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago. I’ll personally match donations up to 5% of annualized revenue for the newsletter, or $500, whichever is larger.

These are the books I’ve recommended this year.

Recommendations are always open. Send in your requests by clicking below and following the instructions.

1. Annie Freeman’s Fabulous Traveling Funeral by Kris Radish

2. The Doctors Blackwell by Janice Nimura

3. Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo

4. In the Country of Others by Leila Simani

5. Euphoria by Lily King

Nancy B. - Chicago, IL

This is a book club request, so I’m not just looking for a good book that differing people will want to read, but also something that supports productive and interesting discussion. I feel like We Run the Tides by Vendela Vida fits the bill on both fronts.

1. The Maid by Nita Prose

2. The Sisters of Auschwitz: The True Story of Two Jewish Sisters' Resistance in the Heart of Nazi Territory by Roxanne Van Iperen

3. Betrayal by Jonathan Karl

4. Agents of Innocence by David Ignatius

5. My First Thirty Years by Gertrude Beasley

Terri M. - Gurnee, IL

Lots of variety in this list which makes for both an easy and a difficult choice because I think as long as I pick something of quality, Terri’s going to dig it. Taylor Harris’ This Boy We Made is going to wind up on some year-end “best of” lists, so it might be good to get to it ASAP.

Paid subscription update

Annualized revenue for this newsletter currently stands at $12,115. So close to the $12,500 mark at which I can afford to start paying outside contributors in order to bring additional weekly book-related fun to your inboxes. If you’ve read this far, I hope you’ll consider supporting this endeavor.

Going to spend a chunk of the rest of my day taking my own advice from this week’s column and get to work on a book I’ve been thinking about for months, but haven’t been working on because I’m worried it’ll never get published.

See you next week,

JW

The Biblioracle

Fortunately, like any sensible person I brought enough books for a trip twice as long as ours, so I had others to choose from.

There is apparently a firm editorial divide between the paper and the book review, which occasionally leads to the same book being reviewed in both places. When that happens, it’s a definite sign that the publisher is pushing the book hard because they think they have a potential hit on their hands.

To the extent that readers know anything about me, they probably don’t know that I actually have some specific credentials in this area, having pulled a couple of different stints as an analyst/strategist for market research companies where I was trained how to think about data by some people who were genuine pioneers in the field, including the guy who showed that there was sufficient demand among mothers for disposable diapers to convinced Kimberly-Clark to launch their product.

Your humble, entirely self-employed, Biblioracle worries about this because if I can’t work, my income dries up almost instantly.

I’ve actually been not a fan for a long time, and even have periodically written him frustrated emails about his serial incuriosity about data. In fact, my first email to him was in September of 2009 about an article on medical malpractice and medical error that I found ridiculously reductive. I recognize I have just outed myself as a huge pain in the ass, but I am what I am.

I am catching up on reading newsletters and so happy I didn't skip this one. I feel the exact same about influencing myself by reading other reviews. I try to avoid them altogether until I've finished reading (sometimes I don't even read the summary of the book beforehand) because I'm so nervous I'm going to absorb someone else's opinion of it.

I also love how transparent you are with the newsletter's finances and where it's going—it makes the reading experience that much more enjoyable!

Glad you had a nice vacation!

I’ve been reading NYTs The Morning religiously for a few years and until recently I had been gladly drinking it up as fact. Perhaps not so strange that my questioning can also be traced back to the very same article you reference regarding us liberals’ ongoing fear of COVID - fears that last well beyond the lingering effects of being boosted. More than just the feeling of “he ain’t talkin’ ‘bout me”, I realized the man behind the curtain had no idea what he was on about. I have since pivoted to letting The Morning Brew reflect my feelings back to me every day over coffee. Great article :)