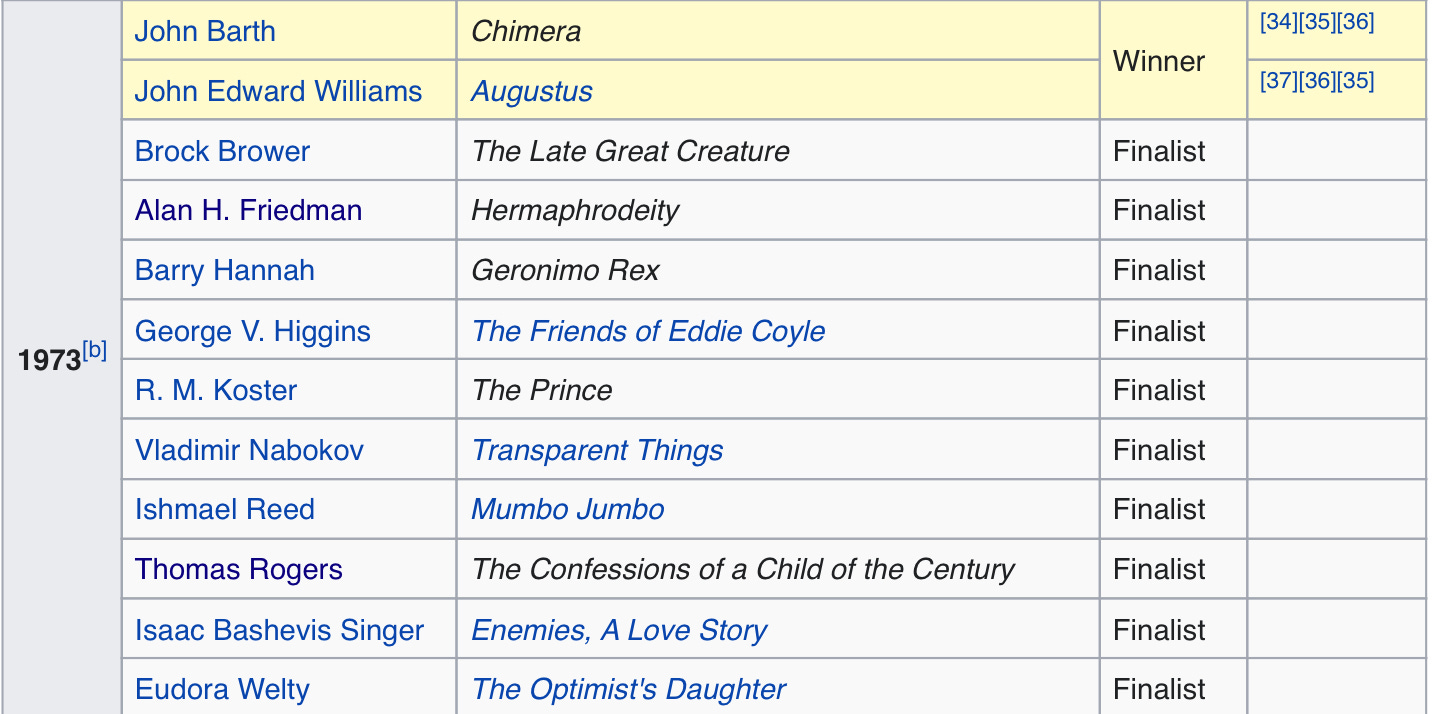

I have recently become obsessed with this list of National Book Award for fiction finalists from 1973.

This obsession is why the newsletter this week is an evening, rather than morning affair, as it has become so deep and varied, the initial draft had three or four different, distinct threads that need their own posts to be sufficiently explored, and thus purged from my thoughts, enabling me to move on to other things, so consider this the possible first in a series.

My obsession originates with my “discovery” of The Confession of a Child of the Century1 by Thomas Rogers in a used bookstore near the Penn State campus. I told that tale in my Chicago Tribune column this week, so I won’t repeat everything, but it involved one of my favorite things to do in a used bookstore, peruse the shelves looking for books that seem like they must have been a big deal at the time they were published, but which I’ve also never heard of.

In the case of The Confession… not only had I never heard of the book, I’d never heard of the author, which is almost extra strange given that he has Chicago roots and was a finalist for the National Book Award for both of his first two books, The Confession… and The Pursuit of Happiness, which is set in Chicago’s Hyde Park area, and even made into a movie starring a young Barbara Hershey.

The Pursuit of Happiness is a very enjoyable comedy, very much of its time that involves a young college student killing a pedestrian with his car and later a murder in a prison shower. That the novel is primarily comedic with those major story points may tell you something about Rogers’ storytelling attack. He’s sort of like a gentile Philip Roth.

While The Pursuit of Happiness is enjoyable, The Confession of the Child of the Century is truly one of the best books I have ever read. I think it’s a masterpiece that combines various modes into what the narrator, Samuel Heather, who is relating his life story, calls a “comical historical pastoral.” Rogers’ tongue is clearly in his cheek, but Heather’s is not, and this tension of a somewhat absurd person telling his life story with utter seriousness on his own behalf creates much of the pleasure of the book.

Heather, born an episcopal bishop’s son in Kansas City, semi-purposefully upends his life by blowing up a chunk of the Charles River riverbank near Harvard (where he is a student) with a stick of dynamite. He winds up going to war (Korea), becoming a communist defector, and even spends time with the CIA.

It is a novel about what it means to be free (or not), faith, love, sex, philosophy, history, the challenges of finding meaning in a world that seems hostile to living a life of integrity, and in a different, perhaps better universe, it would be a classic we still read and teach and discuss, but instead, I couldn’t find a single one of my nearly 18,000 Twitter followers who has even heard of it, or the author.

Rogers passed away in 2007 at the age of 79, having retired from a long career teaching at Penn State in 1992.

On his passing, he did get a New York Times obituary, which is a sign of notability, but imagine, having your first two novels be finalists for The National Book Award and still having your work largely forgotten fifteen years after your death.

It’s enough to make you think none of this tip-tapping away on the old keyboard is worth anyone’s time, but whatever time Rogers spent on The Confession…was worth it because the book is fantastic.

It just seems wrong to me that a book this wonderful and its author should ultimately be largely forgotten. I’m not sure why this bugs me when I’m well aware that the fate of most writers is to be never known, let alone briefly celebrated with major prize nominations and then forgotten, but this feels like an injustice.

Perhaps this is related to something I’ve written about in the past, my great uncle, the writer Allan Seager, who was dubbed the next Hemingway by the guy (E.J. O’Brien) who discovered Hemingway and published numerous books in his lifetime, but also knew, that as Keats wrote on his own tombstone was “one whose name is writ in water.”

Keats was wrong about himself, but my great uncle was correct, and he was not happy about it. His notes and papers from the end of his life show a fair amount of bitterness, including a long rant about that “fraud” William Faulkner.

Uncle Allan published a novel, Amos Berry, that like The Confession of a Child of the Century, deserves to be read and remembered. It actually has a lot in common with The Confession of the Child of the Century, as it’s a novel with a challenging father/son relationship at the center, and both novels explore an inchoate desire to rebel against the status quo that blossoms suddenly in an act of violence.

For Samuel Heather in The Confessions… it’s the blowing up of the riverbank a “prank” which harms no one, but is sufficient to trigger his expulsion from Harvard.

Amos Berry is narrated by Amos’s son, Charles, who is the only witness to the murder of his father’s boss, by Amos himself via a single rifle round fired through this boss’s living room window, the crime covered by a homemade silencer. The novel is really Charles’s attempt to understand his father’s inexplicable act, an understanding that, in its way, give Charles the courage to discard his own bourgeois trappings and become a poet.

Amos Berry was published in 1953, and the New York Times review by John Brooks reveals a cultural blindspot of the era, particularly in its conclusion: “Amos Berry is a social tract, that for all its truths, is as wrong as possible about American life in that it is written without - and describes a life with without - the indefinable redeeming quality of vitality.”

Brooks feels the novel owes it to the reader to be convinced that Amos Berry would do such a thing, but the more interesting question for Allan Seager in the 1950’s was why more people don’t challenge the status quo.

By the time The Confession of a Child of the Century is published in 1972, challenging the status quo had become an expectation, particularly for the young. It’s interesting then that the bulk of Samuel Heather’s telling of his own life happens during the 1950’s, as his adventures bucking expectations mark him as the oddball in the world of the novel.

The brief New York Times Jonathan Yardley review of The Confession… is far kinder to the book than John Brooks was to Amos Berry:

Told in the words of its “author” Samuel Heather, it is an astonishing kaleidoscopic account of coming of age in postwar America, a tour de force but much more — a comic and sympathetic vision of the ageold battle between fathers and sons, a rich, boisterous, satisfying novel that stands confidently on its own as a major accomplishment by, no doubt about it, a major writer.

That “major writer” only published two other books in his lifetime At the Shores (1980), and Jerry Engels (2005).

The gap between Rogers’ The Confession of a Child of the Century and his next book is explicable. Life intrudes, a family, work as a professor that all available evidence suggests he was extraordinarily dedicated to.

But I wonder also if Rogers knew that he’d written a masterpiece, and it would be difficult to impossible to match it.

I wonder what it’s like to suspect you’ve written a great book, sufficient to be called a “major writer,” perhaps alongside Rogers’s friend from the University of Chicago, Philip Roth, and then to realize that more is not coming for you.

Allan Seager published two more novels and a memoir in essays, A Frieze of Girls, which was republished by the University of Michigan Press a number of years ago.

His final book was a biography of the poet Theodore Roethke, who came from the same region of Michigan, and in many ways is also an autobiography of Allan Seager. He hoped that by yoking himself to a poet he knew would be remembered perhaps he too would not be forgotten.

While Allan Seager is forgotten by everyone except me and the people who I can badger into reading about him, the influence of Amos Berry was profound. James Dickey, perhaps best known as the author of Deliverance, but most celebrated as a poet, told Seager that reading Amos Berry is what convinced him to try his hand at poetry. Upon being introduced to Seager by Roethke, Dickey actually said he was “Charles Berry,” a joke Seager did not appreciate.

Seager was working on a novel at the end of his life that his notes make it seem like he intended as a kind of revenge on a readership that had failed to recognize his worth as a writer.

I don’t think he would’ve appreciated me telling him “be not aggrieved,” as I suggested last week is healthy for writers who believe they are not receiving the attention and opportunities they deserved, but he may have left the mortal coil more satisfied with his considerable body of work if he could have embraced the fact that he’d done his best, and done better than most.

While my “discovery” of Rogers was a bit of an old-school, analog world fluke, the digital age makes it considerably easier to pursue these curiosities once they’ve taken hold.

Abe Books, an online marketplace for used booksellers makes it relatively easy to acquire copies of just about any out-of-print book. I now have copies of Rogers’s entire oeuvre, as well as copies of two other books from the 1973 NBA fiction finalists list that I’d never heard of, Hermaphrodeity and The Late Great Creature.

I’m 100 pages into Hermaphrodeity, and it is, to use a technical highly literary term, crazy-ass. It already feels like another book that deserves to be remembered.

Links

At the Chicago Tribune Christopher Borrelli looks at the new golden age of horror.

Christopher Borrelli also had a chance to interview George Saunders, on the occasion of the release of Saunders’s latest story collection, Liberation Day.

Toni Morrison is getting a stamp. About time.

The New York Times has “15 Books Coming in November,” including Toad by Katherine Dunn, the posthumous and presumably final book by the author of Geek Love.

Mike Davis, the groundbreaking socialist writer, and author most notably of City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles recently passed away. This brief tribute from Hua Hsu at the New Yorker, introduces us to some of what made Davis and his work special. In tribute to Davis, his publisher, Verso book has made digital copies of City of Quartz free.

Blue Willow Bookshop, “West Houston’s favorite bookshop” has shared their favorite books of 2022, which includes titles for kids and adults both.

Recommendations

Sorry, no recommendations this week. I’ve been out of town all week and it’s now 7:12pm and I promised Mrs. Biblioracle we’d watch a movie tonight.

As always, I’m accepting requests for recommendations, which you can do by following the instructions at the link below:

What’s the best thing you can do to help this newsletter?

What’s almost just as good? Sharing this newsletter with anyone you think might be interested. The growth in readership lately has been fantastic.

I think we’re going to watch Bullet Train starring Brad Pitt. Good idea, bad idea? Comments are always open for anything on your mind.

Have wonderful weeks, all of you.

JW

The Biblioracle

The book is sufficiently obscure that it’s title is incorrect on the Wikipedia page for the National Book Award fiction finalists. It’s “confession” not “confessions.”

Lovely piece

A very thought-provoking and moving piece. I will be thinking about this for a long time.