I’ve been spending a lot of time this week thinking about thinking.

The biggest thinking-related thing I’ve been thinking about is related to a previous newsletter in which I declared that ChatGPT cannot kill anything worth preserving.

As self-evident as this declaration seems to me and many others, the truth is that it leaves several questions begging, including the most important ones: What is it that I believe is worth preserving? And How do we preserve these things once they’ve been identified?

I’m trying to answer this in the form of a book proposal with the working title Writing with Robots: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. It is profoundly stupid to declare you’re working on a proposal for a book that isn’t sold and may never come into existence, because if the project doesn’t come to fruition you look like a bit of a fool, but perhaps declaring it publicly will light a fire under me to get this thing done.

The truth is that I know exactly what I want the book to be about: thinking and feeling as it relates to reading and writing, two things that large language models like ChatGPT will never be able to do. Unfortunately, writers of my stature are not contracted by publishers for books on a one-sentence general description of content and an insistence that the book is going to be super awesome, so a proposal it is.

That’s okay because writing a book proposal is a great way to do a good chunk of the thinking that will ultimately make its way into the book itself. The trick is to give yourself something concrete to think about. For Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities, the things I thought about involved identifying all of the barriers that seemed to be standing between me and getting my students interested in the work of my first-year college writing course.

When I started writing the proposal I thought it would be almost exclusively a book about writing pedagogy - how to teach writing. But doing the work of thinking through this question revealed that the chief barriers have nothing to do with the knowledge and practice of teaching writing, but are instead rooted in systemic issues like standardized testing, grades, and lack of resources (what I came to call “the other necessities”).

As seems to happen, the more I think about this as of yet, non-existent book that nonetheless has a title, the more I realize my subconscious had been gnawing on the material without me realizing it. A number of newsletter posts over the last year or so feel like they’re going to inform the proposal and the book should it come into existence.

For sure I want to write about the importance of “engagement” as I did here:

I would like to draw a distinction between distraction, which seems to be the M.O. of so much of our digital lives, with engagement, which you get right down to it, is an invitation to think. So much of the energy around ChatGPT seems to be in figuring out how to use it to bypass thinking, which strikes me as a mistake for many different reasons.

And for the kind of writing that is done largely without thinking or meaning, rather than outsourcing it to A.I., maybe we should instead be asking why we’re even doing it in the first place.

I also want to write about how originality is undervalued and the ways LLM technology could be used to either crush or foster originality, depending on how it is employed.

There’s a lot of other parts of the proposal that are at the “notion” stage, which is an idea when it is still at the subatomic level, waiting for the thinking to happen. Honestly, this is one of my favorite parts of the process. If I didn’t feel pressure to get this thing rolling because of the speed with which the technology is making its way into our lives I’d be reveling in the process.

Doing this thinking makes me realize how having the time and space to think is actually something of a luxury, and part of what I want to advocate for in the book is the right of everyone to think, which also means that everyone should have the right to write.

The boosters of A.I language models like to trumpet that the technology has the potential to free people from drudgery, but what if it’s more likely that it denies us access to fundamental human activities, like thinking?

Doesn’t sound like freedom to me.

(Just copied that last bit into the proposal because it captures something I hadn’t quite articulated to myself yet.)

I’m not talking about writing as a disembodied skill either. I’m talking about writing as a tool of self-knowledge, self-expression, and communication with others. These are the experiences students have been cut off from when it comes to writing in school, which makes writing (and even reading) seem strange and foreign to too many people, rather than vital…indispensable!…as we who gather at a newsletter dedicated to talking about books and reading know it to be.

There was a time where I would’ve hesitated to describe a book I’m thinking about working on, lest someone latch onto the idea and take it for themselves, but as I’ve learned over the years, ideas are cheap and easy. I’m sure there’s a bunch of ChatGPT books already heading to the market, but those books are not my book.

A book is in the thinking, and for better or worse, no one is going to think the same book as me.

Thinking Books

If you think about it, thinking is kind of weird. In theory, the barriers to thinking are low. It sometimes happens without you even noticing you’ve starting thinking. My two chief thinking times are the last 30 minutes before I get out of bed in the morning as my brain reaches full consciousness, and whenever I walk the dogs.

It can be hard to think purposefully, as the mind tends to wander, which is why writing is such an invaluable tool for focused thinking.

While the barriers are low, many of use will declare that they just don’t have the time to think. The sheer ubiquity of available distractions sometimes prevents us from thinking, as does a culture that privileges “doing” when thinking is invisible and impossible to quantify. I often have to remind myself to shut everything down and go think.

Sometimes this looks a lot like napping, since I’m stretched out on the couch in my office, but I swear, it’s thinking!

There’s a good number of books on my shelves that make me think about what it’s like to think, and I’m thinking that it might be a good idea to share them to help others think about their thinking.

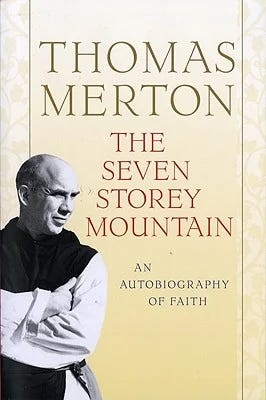

I am not a person of faith, and yet some of my favorite books that model what it means to think are those that show someone grappling with these very large spiritual questions. The Seven Storey Mountain was written by Thomas Merton when he was a young man who gave up his literary career to join a Roman Catholic abbey. Published in 1948, the book was an unexpected literary sensation. Above all, it is a book of mental struggle over Merton’s spiritual life, and the way it is written encourages the reader to reflect on their own uncertainties. It’s a book that will continue to resonate regardless of the passage of time because the questions of what makes us human and the nature of belief aren’t going away.

The first line of John Berger’s The Ways of Seeing is “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak.” Berger is reminding us that we have the power to interpret the world around us even if we have no conscious knowledge of the object of our gaze. We are wired for this interpretation, which is a form of thinking and the series of essays (some of them entirely pictorial) in The Ways of Seeing is like a tutorial in how to make sense of what we see. This is excellent training in general, and demonstrates a process that has proven invaluable to my students as I introduce them to using observations and inferences to interpret the world around them.

Another good productive avenue to travel if you want to think is to tackle a book where you are not a blank slate, but where you indeed have lots of experience and many well-developed beliefs. For me, that’s teaching, so when I read bell hooks’s classic, Teaching to Transgress, it was as though I’d found a conversation partner ready and willing to help me hone my own thinking about this subject and practice of great interest.

How to Think Like Shakespeare: Lessons from a Renaissance Education is almost a how-to for different varieties of thinking that, taken together, add up to a philosophy of education rooted in curiosity, play, and freedom. A good book if you literally want to practice thinking.

In Lost in Thought: The Hidden Pleasures of an Intellectual Life, Zena Hitz makes a case for thinking as an essential good in and of itself, divorced from any other utility, and as the kids probably don’t say anymore, I’m here for it. Hitz left a secure academic job because she recognized that her life as a professor was interfering with the pleasure she took in intellectual pursuits. If a college professor is declaring that they don’t have the opportunity to think, what the heck are we doing? A stirring defense of humanistic thought and the rights of we humans to spend our time doing uniquely human things.

Sometimes the best way to think is to not think. Wilco frontman Tweedy’s How to Write One Song is a class in how to shed self-consciousness and let the creative subconsciousness roam. I have yet to write a decent song using Tweedy’s method, but I feel better every time I shed my rational brain for a little play time.

Similar to Tweedy’s book, Austin Kleon’s Steal Like an Artist is a guide for looking at the world and finding fodder for your own creative pursuits. A big part of thinking is priming the pump of the brain with material that it can gnaw on. Kleon offers honest-to-goodness practical tips that demystify the parts of being creative that don’t need to be mysterious, while maintaining the unique wonder that happens when you are truly thinking creatively.

I could go on and on and on on this front, but I’ll save another batch of good thinking books for a future column.

Time for…

Links

At the Chicago Tribune this week I write about how new revelations from Jonathan Eig’s King: a Life has me rethinking my relationship to Alex Haley’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Martin Amis has passed away at the age of 73. One of the great contemporary stylists, not every Amis book was a hit, but when he did find the target, he was really without peer. Here is a guide to Amis’s books. Here is his obituary in The Guardian. And here is a humor piece from twenty-three years ago in which my friend Kevin Guilfoile imagined what it would be like for Martin Amis to write a fan letter to Britney Spears.

Our on-theme McSweeney’s piece of the week: “Introducing Total Crap, The First Magazine Written Entirely By AI” by Jonathan Zeller.

And that’s the end of links because I spent too much time thinking this week and not enough time trawling my Twitter and Substack Notes feeds for interesting literary links. If you saw some book-related news this week that intrigued you, please share it in the comments for the benefit of the rest of us.

Recommendations

All books linked here go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and the Teacher Salary Project which is advocating to establish a federal minimum salary for teachers of $60,000 per year. Affiliate income is $111.60 for the year.

1. The Mortifications by Derek Palacio

2. The Midnight Library by Matt Haig

3. The Candy House by Jennifer Egan

4. Truly, Madly: Vivien Leigh, Laurence Olivier, and the Romance of the Century by Stephen Galloway

5. The Story of the Trapp Family Singers by Maria Trapp

Karen R. - Beverly Hills, CA

I think Karen will be swept up in the setting and story of Jess Walter’s Beautiful Ruins a tale of Old Hollywood mixed with contemporary challenges of living.

So, how do all of you go about making a practice of your thinking? What activities, behaviors, and books do you recommend to cultivate a life of thought?

Please feel free to share in the comments.

That’s a wrap! See you all in a week’s time.

JW

The Biblioracle

I will be the first to buy this book!! Go, go, go!!

Absolutely love the book proposal, and I cannot think of anyone better to tackle the topic