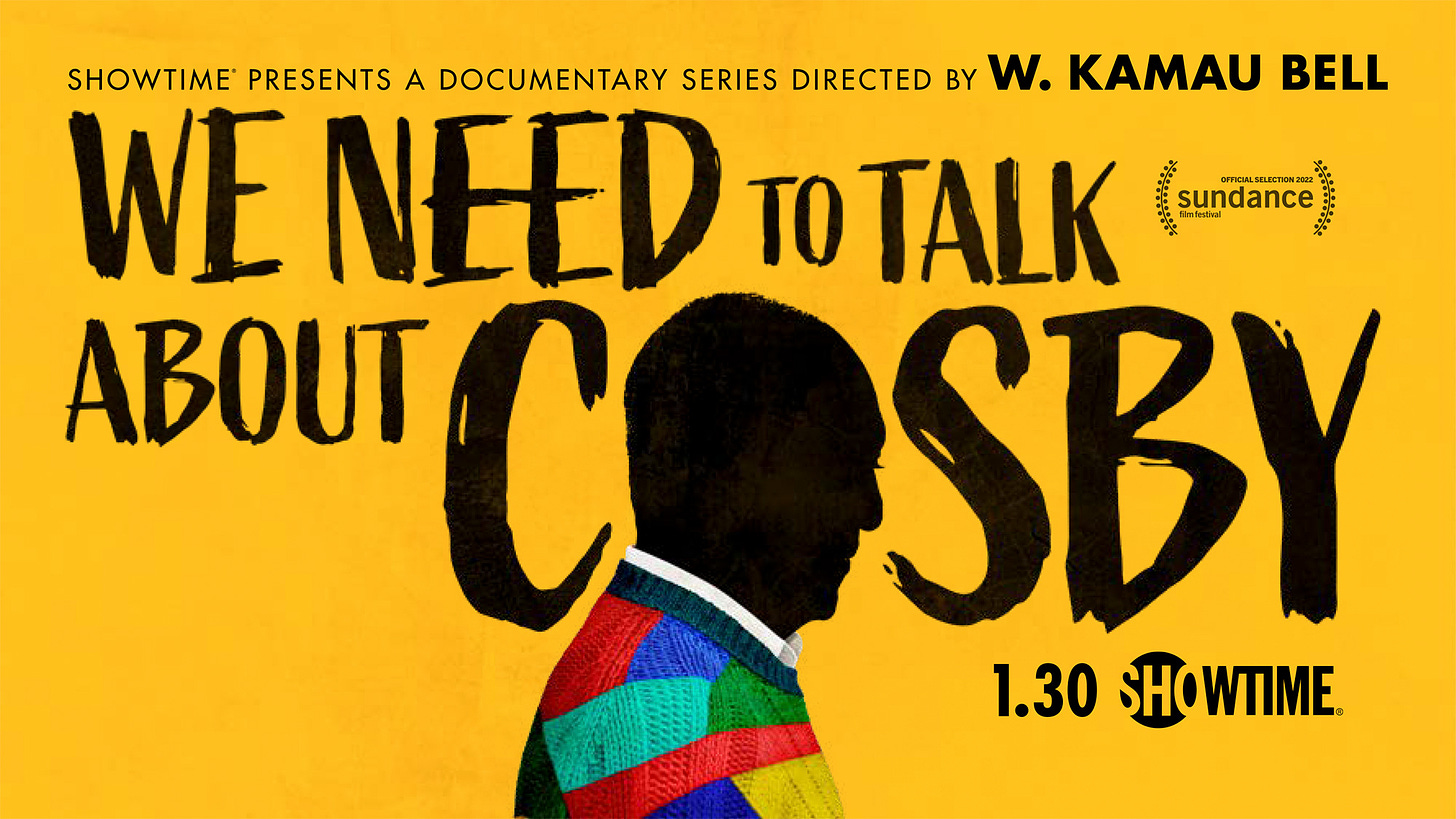

Thinking About "We Need to Talk About Cosby"

Why you can never separate the art from the artist.

I watched W. Kamau Bell’s four-part documentary, We Need to Talk About Cosby, in a single day, and I’ve been thinking about it every day since.

As a kid from an overwhelmingly white Chicago suburb growing up in the 1970s and 80s, it is not an exaggeration to say that Bill Cosby was my primary conduit to the lives of African-Americans.1 I remember first hearing Cosby’s stand-up routines about the neighborhood kids (that would become the fodder for Fat Albert) on a closed circuit radio feed pumped into the rooms at the Winter Park, Colorado ski lodge where my family would stay on vacation. Once I’d exhausted the roll of quarters I was allotted to play Space Invaders and Tank Battle, the lone entertainment was that radio feed, Bob Newhart, Bob & Ray, and Bill Cosby’s “buck buck” routine about a neighborhood game that ended in disaster once Fat Albert came on the scene.

I memorized that routine. I could probably still recite huge swaths of Cosby’s 1983 comedy special, Himself as well. The bit about feeding his kids chocolate cake for breakfast (“Dad is great! Give us the chocolate cake!) was exactly what our dad would have done if he ever had to figure out our breakfast.

The Cosby Show was The Cosby Show, the biggest show on television for a time, but I preferred the spin-off A Different World, set at fictional HBCU Hillman College, which ran during my own college years, and just like Cosby’s chocolate cake routine, simultaneously demonstrated the experiences that we all hold in common while introducing me to the cultural specifics of majority Black spaces.

All things considered, Bill Cosby was probably the most notable and influential entertainer of the first half of my life.

Jello pudding pops!

When Cosby’s life as a sexual predator became public and undeniable, I did what I’m supposed to do, I vowed to stop consuming Cosby’s work, doing my individual part at making sure Cosby was remembered not as a great comedian and entertainer, but a serial assaulter of women.

We Need to Talk About Cosby is the story of how this stance is something of a luxury belief, made possible by that white suburban upbringing where Cosby was just an entertainer I once liked a lot. In his film, W. Kamau Bell has a much more nuanced and important story to tell, and he does it in a way that does not flinch for a moment from conveying the full truth of Cosby’s actions.

The film is notable for its craft, as Bell makes a number of choices that provide deep and meaningful context to a story that most of us probably feel like we already know - a powerful man used his power to act with impunity, the same dish with a slightly different flavor as Harvey Weinstein or Jeffrey Epstein. Bell’s mission is to demonstrate to the audience that the details very matter.

One of Bell’s moves is to create a graphical timeline that intertwines Cosby’s career trajectory with the more than 60 documented reports of claims of rape and sexual assault. Bell illustrates how even as Cosby is ubiquitous on children’s television with Fat Albert and Picture Pages on Captain Kangaroo, he is drugging and assaulting women.

We see both Cosby’s insistence on using his clout to finally integrate the profession of stunt actors - prior to Cosby, white stunt performers did the parts in blackface - and his predation on women, and both are both are given as much space as necessary to tell those stories.

I do not know why this juxtaposition struck me so powerfully. I suppose I’d been thinking that Cosby was the story of a powerful man who took advantage of that power, and this is undoubtedly true, but it is also quite possibly the story of a man who acquired this power in order to act with this kind of impunity. Bell plays a number of clips and interviews where Cosby is very up-front about his fascination with the alleged aphrodisiac “Spanish fly,” and how great it is when women are left powerless in the throes of sexual ecstasy.

In hindsight it is like a serial killer bragging about his M.O. in public, and you start to wonder why it only reads like this in hindsight.

Another powerful choice is allowing the women who were assaulted to tell their stories directly to the camera at length, with minimal (if any) cutting away in the interests of narrative. At the time of telling, the entire focus is on the women, and Bell does not move on until they have exhausted what they have to say, occasionally gently probing with questions off camera. We hear the full context of each incident, the way Cosby used his prominence to bring the women close, how his status and image provided an initial level of comfort, the way he would instruct (or even demand) that women take pills or drink what we now know to be a spiked beverage. We see the women’s excitement over meeting a celebrity, the uncertainty when things get weird, the self-loathing after they realize they’ve been taken advantage of, the anger that comes after the self-loathing. Each story bears significant, distressing similarities, but by allowing each woman to have her voice, Bell gives both the individual and collective stories more power.

I could go on and on how extraordinarily deft the film is in how it tells its story, but even more important is the story it tells, and not for the part of the audience that consists of people like me.

The most prominent voices in the film after those of Cosby’s victims are those of Black writers/commentators/public intellectuals (Renee Graham, Todd Boyd, Marc Lamont Hill, Jamilah King, Tressie McMillan Cottom, Jelani Cobb, and many others), and it becomes clear that the “we” Bell is talking about in his title certainly means everyone (as in all of society), but he is primarily focused on the Black community, for whom Cosby was so important. This is the man who told their stories in ways that made them legible to white people while still being recognizable to Black Americans.

I highly recommend this Tressie McMillan Cottom essay on her decision to participate in the documentary, and what Cosby and The Cosby Show meant to the Black community, the way Cosby simultaneously affirmed the story of Black progress in America while honoring the roots of generational struggle that animate Black culture.

Over time, Cosby’s reputation curdled in some corners of Black America as he leaned all the way in on respectability politics, either dismissing or downplaying the problems of systemic racism. In the documentary, Marc Lamont Hill tells a story of an exchange with Cosby over this issue that I will not spoil, but which seems to wholly capture what moved inside the man.

The story of Cosby and the women he assaulted is the primary narrative of the film, but as the episodes progress you see that Bell has also been building a story of collective confusion and heartbreak, as represented by the public intellectuals he enlists to discuss Cosby. There are moments where you can read the grief on a commentator’s face when they explain who Cosby is, who he always was.

In her essay Cottom captures this complexity, arguing that there should be no retroactive guilt over once Cosby. She writes, “We were not foolish to enjoy The Cosby Show or to need what he was selling. Even if you did not live in Compton or New York or Chicago in the 1980s, the racist tropes used to legitimize the war on drugs affected all Black Americans. We were not wrong to look for progress in culture as economic progress stalled and declined.”

Bell’s film shows that while Cosby may have saved millions of lives, he was no savior. Cottom says this is because there is no savior, as much as we’d like to believe in such things, “What we wanted from Cosby is what a child wants from a parent: an illusion of security. But as the Bible says, there is a time for putting away childish things. His carefully cultivated facade was always as much about what we needed from him as it was about anything he created for us. Adults have to face reality.”

We Need to Talk About Cosby makes clear that it is a cop-out to fall back on the old “separate the art from the artist” trope no matter which side of the divide you fall on for a particular figure.

As Cottom says, it is the responsibility of adults to wrestle with the world, and see what we come to know through that struggle.

W. Kamau Bell’s film is a brilliant testament to what’s possible when someone is brave enough to look as directly as possible at the most painful things, and the result is something profound, and terrible, and beautiful all at once.

Links

My Chicago Tribune column this week explains why it is not only perfectly normal, but even desirable to read in a bar.

This is really fun. The New York Times looks at the full production process of Marlon James’ new novel, Moon Witch, Spider King.

For all you Chicago folks in the readership, Adam Morgan has compiled a list of Chicago-related books to be released in 2022. I’ve bookmarked it for future reference.

Libraries are absolutely one of our most important democratic institutions, and over at LitHub Ilan Stavans explores how “American Literature is a History of the Nation’s Libraries.”

Great interview with Min Jin Lee, author of Pachinko, in The New Yorker this week.

Conservative satirist P.J. O’Rourke passed away this week. Most of the commentary is focused on how he was a dying (or already extinct) breed, which I generally agree with. I’ve read a bunch of O’Rourke over the years and generally enjoyed his work, but like just about all satire it curdles over time. Times and tastes simply change.

Recommendations

All books linked below and above are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Steady progress on affiliate income, now totaling $35.10. I’ll match any total up to 5% of the annualized revenue for the newsletter or $500, whichever is larger, as a donation to Open Books.

The list of 2022 recommendations will be filling up week by week.

Recommendations are always open. Send in your requests by clicking below and following the instructions.

1. Empire of the Vampire by Jay Kristoff

2. Two Rogues Make a Right by Cat Sebastian

3. The Inside Edge by Ashlyn Kane

4. A Hat Full of Sky by Terry Pratchett

5. She Came from the Swamp by Darva Green

Jessica - New York

I have had this book in my back pocket for months, just waiting for the right reader to come along, and I think Jessica is a good candidate for Paul Rudnick’s same-sex com-rom (that’s a romantic comedy where the comedy comes first) in which a New York even planner hooks up with an heir to the British throne, Playing the Palace.

1. Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus by Leon Kass

2. Red Bones by Ann Cleeves

3. Fair Warning by Michael Connelly

4. The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth by Sam Quinones

5. The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman

Mark - Robinson, IL

Whenever I see someone who is into series of mysteries I’m hoping they haven’t yet tried Anthony Horowitz, most specifically is “Hawthorne and Horowitz” series, in which he casts himself as the sidekick to a great detective. The first in the series is The Word is Murder.

Paid subscription update

Annualized revenue for this newsletter currently stands at $11,863. We are tantalizingly close to the $12,500 mark at which I can afford to start paying outside contributors in order to bring additional weekly book-related fun to your inboxes. If you’ve read this far, I hope you’ll consider supporting this endeavor.

I never lack for ideas to write about, but if there’s anything you’d like to see me explore in more detail either here or at the Chicago Tribune, you can reach me by replying to this email or even better, writing directly at biblioracle@substack.com.

Have a good week, everyone.

JW

The Biblioracle

The music of Motown, a favorite of my father’s, would probably be number two.

Jeff Deutsch has written a book about bookstores? Note to self: order that book - from Seminary Co-op, of course!