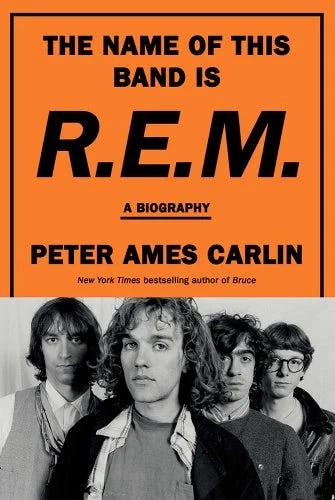

As I wrote in my review of Peter Ames Carlin’s new rock biography, The Name of This Band is R.EM, R.EM. was the first band that felt like they belonged to me. Prior to that the music I listened to was from before I was born (Beatles, Led Zeppelin), or handed down by my parents (Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder). Sure, it was my college-age older brother who introduced me to the band, but from the moment I heard them, something clicked.

It’s hard to believe I’ve aged to the point where definitive rock biographies are being written about my music, but such is life. I was pleased to be able to ask Peter Ames Carlin about some things I was curious about, and go deeper on the story he tells so well in the book.

—

Peter Ames Carlin is the author of The Name of This Band is R.EM., Bruce, and Sonic Boom, among other books about music and musicians. A professional writer since 1985 he’s been a senior writer for People magazine, a TV critic/columnist for the Oregonian newspaper in Portland. His writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, Esquire, The Atlantic.com and elsewhere. He lives in Seattle, Washington.

John Warner: As I say in my review, while I was reading your book, I’d put on the R.E.M. album that corresponded with the era you were covering, and that experience reminded me of something important: This band was really good!

Peter Ames Carlin: Yeah! They were so inventive and so daring throughout their career, even the stuff that didn’t work as well as some of the other stuff is kind of fun to listen to, and interesting to think about. And the truly great stuff – and oh boy is there a lot of that – is revelatory. And, I think, pretty timeless. For instance, R.E.M. is maybe the only band I can think of that got out of the ‘80s without making even a single album or song with those big booming drums and burbling synths that wound up diminishing a lot of bands’ otherwise decent work of that moment. They had really good taste about that kind of stuff.

JW: My gateway to R.E.M. was a four-years older brother who was tapped into college music and influenced my taste via exposure, though we never became carbon copies of each other. I remember he was into groups like The Waterboys and Guadalcanal Diary, which did nothing for me, while simultaneous to my early R.E.M. fandom, I was into the proggy stuff of Genesis. What do you make of the fact that a band so specific as R.E.M. ultimately had such a broad reach?

PAC: The band was made up of four super creative guys, each with his own set of influences, so listeners from all across the spectrum could find something to draw them in deeper. The magic in their chemistry. I think, was how generous they were with one another, and how eager they were to absorb one another’s influences and ideas, and spin them into something unique that was truly their own.

JW: How did you come to the band?

PAC: I was aware of them from the early ‘80s, having read about them in Rolling Stone and being a regular ‘Late Night with David Letterman’ viewer in 1983. I was living in Portland, Or at the time though, without access to a good college radio station or any left-of-the-dial type outlet that would play their music so it took another few years for me to really listen and connect with them. I’m often late to the new big thing, but when I dive in I tend to go deep and do a thorough retrofitting. And now it’s been like 35-plus years so it’ s hard to remember ever not listening to them.

JW: These guys were obviously good musicians, but they also weren’t virtuosos. Other bands in the early Athens scene (most notably Pylon) also were also more about making a band and then figuring out how to play. But it’s not quite a punk aesthetic. It seems like a time and place where lots of people were interested in, for lack of a better word, “art.” It’s interesting to read the book and see how much the milieu these guys were immersed in shaped their attitudes and their music.

PAC: Yeah, so much of what happened in that Athens art band scene of the late ‘70s and ‘80s – from the B-52’s to Pylon to R.E.M., Love Tractor, Limbo District and on and on, can be traced to the University of Georgia’s Lamar Dodd School of Art, where so many of the musicians, including Michael Stipe, studied. The art school was a magnet for bohemian and art-forward kids from all over the southeast, and because its faculty was full of practicing artists who had been hired by then-school chairman Lamar Dodd in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, it was full of bohemian arty folks who shared a kind of avant-garde sensibility. Several of the professors were musicians themselves, or serious students of music and culture, and they recognized the connections between high art and folk culture, and between art and, from the mid-70s forward, punk rock. Artistry, as they understood it, was not always about masterful technique. As they told their students, it was about originality and expression. Judy McWillie, who taught painting to Michael Stipe and members of Love Tractor and (I think) Pylon, had a vivid memory of talking to Michael and a few other students while they were working at their easels in her class, and when they asked her if you needed to be a Clapton-like virtuoso in order to get across as a musician she told them: “If you can’t play it on a $50 guitar from Sears it ain’t rock ‘n’ roll.” The students were listening.

JW: They were also clearly a “band” with the whole being greater than the sum of the parts. I’m curious how you feel about this, but to me the post-Bill Berry material isn’t the same. Not even commenting on its quality (though like a lot of fans, I find it not as good as the earlier stuff), it’s just plain different without his presence. Do you agree? Was there an essential quality missing?

PAC: It’s plainly different, because Bill was such an influential and important part of their collaboration. All drummers, particularly the distinctive ones (Charlie Watts in the Rolling Stones, Dave Grohl in Nirvana) are hugely important to a band’s sound, and Bill was a smart, creative drummer. But he was also a multi-instrumentalist and composer who had a big hand in some of the band’s most distinctive sounds. “Driver 8,” “Perfect Circle,” “Everybody Hurts” and “Man on the Moon” all contain defining riffs and chord progressions that were composed by BIll. He also served as an editor for the other members, and served as an editor for the others, helping to structure their ideas and keep their more self-indulgent flights of fancy into check.The question of whether the other stuff was as good: that’s a matter of personal taste, and maybe it’s inevitable that a band or artist will eventually fall away from the urgency and intensity of their earlier years. But I love a lot of their later albums, and I suspect that if “Accelerate” had come out in 1995 it would have been a huge smash. Sometimes it’s your time, sometimes it isn’t.

JW: This is your seventh work of music biography, but the first time you’ve done a group. What’s different between writing about an artist (Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen, Brian Wilson), and writing about a collective?

PAC: Oh, this is something I really want to talk about because I went into the project knowing that I wanted to do something a little different with the structure and rhythm of the R.E.M. book. I wanted to build on what I’d done with SONIC BOOM, the book I wrote just before this one. SB isn’t a biography in a traditional sense, it’s a history of Warner Bros Records, and weaves together the lives and exploits of a bunch of significant characters, e.g., Mo Ostin, Lenny Waronker, Joe Smith, Stan Cornyn, and a few others. Writing about R.E.M., offered a variation of the same problem: how to weave several characters into a shared narrative. When I started thinking about R.E.M.I knew I wanted to play around a little with structure, if only because R.E.M.’s music so consistently challenged and altered basic ideas of song structure. It occurred to me that I should try to do something similar with the structure of the book. What I eventually hit on was the idea of dividing the book into five sections, with each coming in large part through the experiences of an individual band member, and the fifth focused on the band’s legacy, as viewed through the audience’s experience of the band. I wanted it to be a sort of subtle shift from section to section, the trick was to not lose touch with the band members who were less central in the story at that moment. But I think the evolution of all their personae, and in their collaboration, is on view throughout the thing.

JW: Finally, the last question I ask everyone. What’s one book you think is underappreciated or under read that you think others should know about?

PAC: Hmmm. It’s hard to pick just one. I’m a big fan of Jess Hopper’s memoir, Night Moves which is such a sweet tale of her life as a young music fan/writer in Chicago in the early ‘00s. I was also delighted to be able to read an early copy of a novel that is unknown because it hasn’t come out yet, but I think people should look for: It’s called Deep Cuts, by Holly Brickley, which is about young music-centric folks growing up in and around the music scenes in the Bay Area and New York, and it’s a very sweet tale full of delightful characters, and put me in mind of Sally Rooney’s books. And if that weren’t enough, it turns out that Brickley is a fantastic music writer, so her central character, who is also a music writer, drops these insights into music and musicians that were hugely insightful and fun to read.

Previous recent author Q&A’s:

Echo Chambers of Our Own Devising with Charles Baxter.

Crime Novel? Women’s Fiction? Literary Thriller? with Kelsey Rae Dimberg.

Everybody Is Secretly Grieving with Alison Espach.

Observations Within Landscape with Ben Shattuck.

I'm excited to read this one. Carlin did a great biography of Brian Wilson that I think is pound for pound the best of the Beach Boys books out there

Thanks for this. REM was the most important band for much of my youth. What a bunch of magnificent weirdos. Looking forward to this book!