Echo Chambers of Our Own Devising

A Q&A with Charles Baxter on "Blood Test" and other things.

Charles Baxter has been one of my favorite authors for a long time. I first remember reading his short stories as a graduate student somewhere around 1994 or 1995, when my friend Nick Johnson pressed a copy of the collection Through the Safety Net into my hands. The title story is a weird and funny work of suspense that I used to read out loud to my introductory fiction writing students to remind them of what it’s like to be captured by a story. His novel, The Feast of Love was a National Book Award Finalist.

A couple of weeks ago I included his novel Saul and Patsy as one of my favorite love stories.

Baxter frequently writes essays on the craft and experience of reading and writing fiction, including Burning Down the House: Essays on Fiction and Wonderland: Essays on the Life of Literature.

I’m also pleased to note that he wrote the introduction for a reissue of one of my great uncle Allan Seager’s books, A Frieze of Girls.

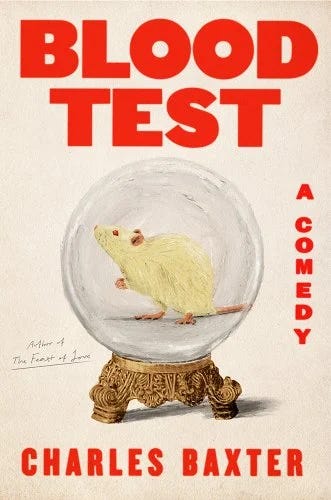

Baxter has published many other books, all of which are worth your time. The occasion for our conversation was the release of his new novel, Blood Test: A Comedy, which I reviewed recently at the Chicago Tribune, and which is a truly wonderful reading experience.

We corresponded asynchronously over email.

John Warner: The other week I was being interviewed by a 15-year-old high school sophomore for their class project on being a writer, and one of the questions was, “Why do you keep writing?” In this student’s mind, I think I seemed like someone who should’ve packed it in by now, retired, been put to pasture - “I’m only 54” I told her, which wasn’t persuasive. But answering the question forced me to really think about what it is that I find compelling about the experience of writing. So I’m going to ask someone who’s been at it longer than I have: Why do you keep writing?

Charles Baxter: Much of the time I’m not writing. I’m going about my life doing my usual routines. I often experience long dry spells of non-inspiration. I keep at writing–when I do it–simply because it’s a skill and a craft I’ve learned, and it may be the one thing that I’m good at. Sometimes certain situations or stories suggest themselves, and I set to work. I fall into the dream of the story, and it takes hold of me. I’m in its grip. That’s when the sentences start to flow.

JW: I’m curious about the choice to explicitly label Blood Test as “a comedy.” Reading the book, the comedy seems fairly obvious - It’s funny! - but I suppose there’s also a specter of danger and threat, given what is predicted by Brock’s blood test.

CB: When I started writing the book, I couldn’t decide whether it was a comedy or a thriller. A few chapters in, I decided it was a comedy but also a page-turner. It’s not really a satire, though it has some satiric elements. Anyway, I thought I had better label it “a comedy” because the title seemed to promise mayhem and a landscape of corpses, and it’s not that kind of book, although one reviewer in Boston was disappointed that there wasn’t more violence in it.

JW: In the novel, Brock Hobson is deliberately framed as an ordinary man with and ordinary life that is suddenly unsettled by this blood test which augers dark events in his future, things he will do that he would see as out of character, but which he also experiences something he hadn’t felt in a long time, “freedom.” What do you see him as being freed from?

CB: His routines, his settled habits. It’s an old story: someone comes along and tells you what you’re going to do, or what’s going to happen to you, and your life may skew in that direction. Ask Macbeth. That’s what happened to him.

JW: Blood Test is set in the aftermath of the worst parts of the Covid pandemic. It’s present, but not oppressive, managing the challenges of the pandemic are no longer central to the lives of the characters. But for me, it very much seems like a Covid novel in that I get the sense the characters have been unhinged, or even a little deranged by the experience of the pandemic. How important is setting the novel in this period of time to how you think about the story?

CB: Very important. Covid got many of us into the habits of solitude, and social distancing, and the feeling that no one was listening to us. We were in echo chambers of our own devising. I think many people are still in those echo chambers. Conversations changed: more and more people started to launch into monologues. We’re still there.

JW: I’m curious about your approach to dialogue. I’ve been searching for a way to describe it, and the best I can do is that your characters speak in a kind of distinctly “American” vernacular, where they’ve absorbed the language of television sitcoms, of commercial marketing, of online slang, of legal disclaimers, like they’re big balls of velcro that any kind of cultural bric-a-brac may have adhered to, and now comes out of their mouths. The exchanges between Hobson and the Generomics people are illustrative, I think.

CB: Thank you. That’s what I was aiming for. The Generomics people engage in a kind of corporate gobbledygook. We’re surrounded by that kind of language. Donald Barthelme once called the commercial junking-up of language as “the leading edge of the trash phenomenon.” I tried to get that effect into the dialogue–also the sense that people are not really listening to each other as much as they once did.

JW: Speaking of language and gobbledygook, I recently went back and re-read the opening essay from your collection Burning Down the House: Essays on Fiction, “Dysfunctional Narratives: or: ‘Mistakes Were Made.’” The essay uses Richard Nixon’s famous declaration of Watergate (“mistakes were made”) as an illustration of what you call the “disavowal movement,” an era where “deniability” takes center stage in our public narratives. (I’m now thinking about Bill Clinton saying “It depends on what the meaning of ‘is,” is” in parsing his relationship with Monica Lewinsky.) You’re concerned that we have lost a sense of agency in our characters and our narratives you say you’re “nostalgic for stories with mindful villany, villany with clear motives that anyone would understand.” This essay resonated strongly with me when I first read it and maybe resonates even more strongly today. Lefties like me do a lot of complaining about how legacy media like The New York Times softens what we see as Trump’s villany through giving him gateways to deniability. A recent example is a headline that declared, “Trump’s Remarks on Migrants Illustrate His Obsession With Genes” when in reality he was just saying racist stuff about non-white minorities. It’s like the virus Nixon infected us with is now so pervasive we don’t notice it any more.

CB: Your comment is eloquent and right on the money. So many public figures are trying to disavow any responsibility for bad outcomes; we end up suffering from brain-fog as a result.. We don’t want to overstate how awful some public figures are. Those disavowals, the refusal of responsibility, are everywhere in public life and, as you pointed out, in the media. Everybody, except saints, sooner or later does bad stuff. You have to own up to it.

JW: You’re a Midwesterner, born in Minneapolis, I believe, and you spent your professional years at a series of Midwestern institutions (Wayne State, U. Michigan, now U. Minnesota). Do you see yourself as a “Midwestern writer” or are these regional distinctions not meaningful to you as a reader or a writer?

CB: I used to think that I was a writer who happened to live in the Midwest. I was not a Midwestern writer, a phrase that seemed condescending and limiting. But that changed. If someone now calls me a Midwestern writer, someone whose stories have something to do with living here, I’m okay with it. With the internet and the mass media, we’re all much less regional than we used to be, but regional elements persist, as does a certain Midwestern temperament. So, okay: all that goes into the fiction.

JW: As a Midwesterner who has lived in the South for almost 25 years now, and for whom the Midwest will always feel like “home,” while the South never will, I’ve spent some time thinking about how the Midwest manifests itself in stories. I don’t know if this will make sense, but something I think about is a Midwestern attitude where characters may have a “reason” to despair, but that doesn’t necessarily give them a “right” to do so, that despair is always present, but also not to be given into. I’m thinking of the characters in Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, or the work of a writer I know you know (but most don’t) my great uncle, Allan Seager, whose books were filled with anger rooted in despair, but which also refused to allow characters to wallow in those emotions.

I’m looping back to the idea of the importance of agency you talk about in “dysfunctional narratives” I guess. Exercising the agency available to you, even when constrained, seems like a very Midwestern thing to me. Brock Hobson seems cut from this cloth. The reviewer who was wishing for more violence is maybe picking up on the idea that Brock would be justified in unleashing some. He’s even been given permission of a kind to give in, but he doesn’t leap at it. I don’t know what I’m saying other than it seems very “Midwestern” to me.

CB: I once found myself answering a question like yours by saying that Midwesterners often have a feeling for limits–they see what they could do, call that “extreme remedies,” but they don’t do it. It’s as if we know how dark our lives can be, but you don’t give in to that kind of darkness, that nihilism, just as you don’t give into the most flagrant forms of ambition. Even Toni Morrison’s characters have a certain interesting resilience, and she was from Ohio, just as Sherwood Anderson was. It’s hard to make generalizations about regions, and much of what you’re likely to say is wrong, but the Midwest has been my imagination’s home all my life, and I’ve come to think that there’s a distinctive way of being–of feeling–here. Outsiders sometimes think that Midwesterners are a bit simple, or dense. I just think they’re guarded. They don’t want to let you into their secrets before they have to.

JW: My last question is the same question I ask everyone. What’s one book that you think people might not have heard of that you think more people should read?

CB: There are so many. But the one I like to cite–because I think it’s beautiful, and maybe one of a kind–is William Maxwell’s So Long, See You Tomorrow. You can read it in almost one sitting. But it’s so intricate that you can’t get into its depths with just one reading.

Previous recent author Q&A’s:

Crime Novel? Women’s Fiction? Literary Thriller? with Kelsey Rae Dimberg.

Everybody Is Secretly Grieving with Alison Espach.

Observations Within Landscape with Ben Shattuck.

Definitely sold me on ‘Blood Test’

Not sure if I saw Mink River by Brian Doyle in your writing. Very much enjoyed it! Glad you are still writing. Your columns are well worth reading. Thank you.