Jane Austen, perhaps the greatest novelist in the history of the English language, died nearly broke at the age of 41 in 1817.

She made very little money from her writing in her lifetime. For most of it, she wasn’t even known as the author of her own novels, having published Sense and Sensibility as “A Lady.”

The reasons Austen was broke had much to do with the time she lived, her gender, and her social station. Her mother came from gentry, but her father was a parson who left his family without money or support when he died. Austen also never married, famously rejecting marriage for station over affection.

Now, the present-day Austenverse rivals Marvel and Star Wars for its spawning of entertainment properties, including this forthcoming “twist” on Persuasion, starring Dakota Johnson.

But in her time, Jane Austen didn’t come close to “making a living” as a novelist. I think about that all the time.

I’ve been thinking about Jane Austen, broke novelist, because the “fewer than 1% of books sell 5000 copies” factoid has been bouncing around my online world again.

Even if that 1% stat is pretty dubious, as my friend and publisher Anne Trubek argues at her Substack, “Notes from a Small Press,” it’s indisputable that the vast majority of books do not find much readership at all.

This is even more true for novels than books in general. I read between 60 and 70 new works of fiction a year, and yet I already have a stack of unread 2022 books I’ve either bought or requested from publishers larger than what I will get to this year. If someone whose job is to read a lot of novels can’t come close to reading even a fraction of the new novels in a year, what chance does someone have to be a “novelist” as their profession?

I try to keep in mind that not being able to make a living as a novelist is more like the longstanding status quo in this country, rather than something once well-established that’s been lost. Cathy Davidson’s Revolution and the Word: The Rise of the Novel in America argues that well into the 19th century, there was literally no mechanism by which a writer could make a living as novelist in America. Her book traces how the idea of the novel and novelists had to be supported by a system of commerce which allowed for novels to be distributed, bought, and read before writers could expect something like a real income from their writing.

For “novelist” to become a viable job, America needed to evolve both its culture and its economics.

And it did!

Mark Twain is perhaps the first, or at least the most famous early example of an American writer who makes a living from his writing. By all accounts Twain made lots of money from his writing that he unfortunately plunged into failed late 19th century start-ups.

By the first quarter of the 20th century, the publishing houses whose names still grace the spines of what we read (Knopf, Holt, Harper) had arisen out of the early, post-revolution printing and publishing network, and there was an infrastructure in place to support the work of novelists writing and publishing fiction. This (along with some inherited wealth in some cases) is what allowed for Gertrude Stein’s Paris salon of expats including Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, and F. Scott Fitzgerald to hang out, think and speak big thoughts, (and pickle their livers), in between writing and publishing books.

During the Depression, the Federal Writer’s Project stepped in to help keep writers - including Ralph Ellison, Nelson Algren, and Richard Wright - afloat.

Add in the array of periodicals such as the Saturday Evening Post, Esquire, Vanity Fair, that came to be known as the “slicks,” which published short fiction for amounts that would rival what midlist writers receive as advances for entire books today, and you had a system that could support a fair number of people in the work of writing fiction.

I have something of a unique window into this era through a family connection, a great uncle - my father’s uncle - who, for a time, was very hot stuff on the American literary scene. But you’ve likely never heard of unless you are related to me, or are such a regular reader of my work you’ve read something else I’ve written about him.

His name is Allan Seager, and E.J. O’Brien, the original editor of what would become the Best American Short Stories annual (established in 1915, still publishing today) once told a radio interviewer that the four best short stories written by Americans were “The Undefeated” by Ernest Hemingway; “The Triumph of the Sea” by Sherwood Anderson; “Sherill” by Whit Burnett, and “This Town and Salamanca” by Allan Seager.

(If you want to read the story, and an introduction to Seager and his work, McSweeney’s hosts both a reprint of “This Town and Salamanca” and an introduction to Allan Seager written by Charles Baxter.)

I have photocopies of some of Allan Seager’s personal papers that have been retained by the family, and they provide interesting insights into what it was like to be a writer in that era.

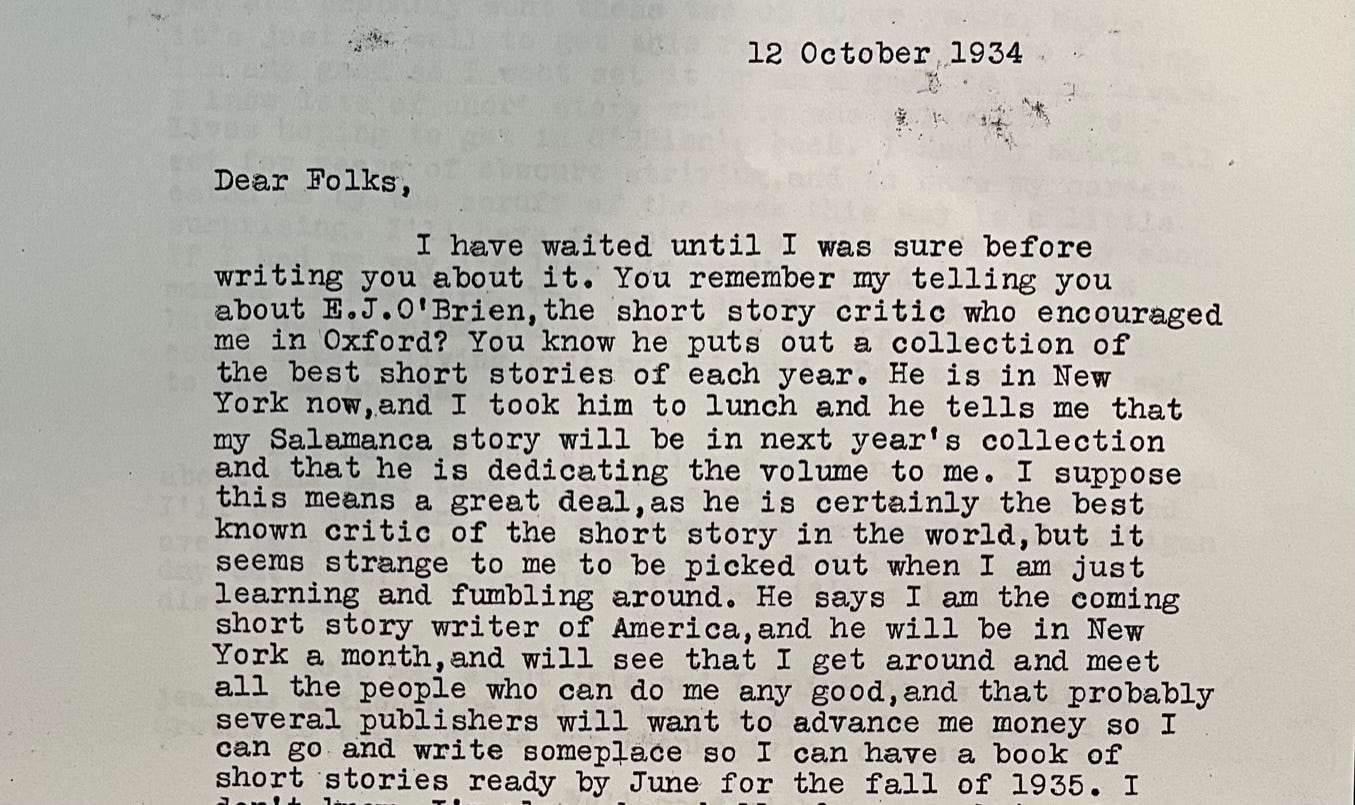

A letter from October 1934 when Allan Seager would’ve been 29-years-old reflects both his excitement and fear at finding out that O’Brien would be putting “This Town and Salamanca” into the Best American Stories anthology.

O’Brien was a part of the infrastructure that allowed those who were writing to become “writers” acting here as a kind of talent scout who tapped my great uncle as a person of promise. One of his earlier “discoveries” was Ernest Hemingway.

Allan Seager had a quite remarkable life, a national champion swimmer, Rhodes Scholar, editor at Vanity Fair (which is where he was working when O’Brien found “This Town…”). His bout with tuberculosis contracted during his Rhodes Scholarship and the enforced rest both accelerated his growth as a writer and provided fodder for his first published short story, called “The Window,” which was ultimately plagiarized and bowdlerized into a kind of folk tale divorced from its author. (I wrote about that for The Morning News years ago.)

A combination of bad luck and a somewhat prickly nature hamstrung Allan Seager in his efforts to be acknowledged as the great writer he thought he could become.

In that same letter telling his family about O’Brien tapping him, he recounts a literary party in New York where he was “griped” because he could no longer observe because, “here come these prigs wanting to talk to me because they know what O’Brien says. They want to see if I have any stuff because they write and they are jealous of anyone new. And smug as hell, all of them, you’d think they’d done something. I got drunk on absinthe cocktails and was rude to a couple of them…I just don’t like literary people en masse; they may be all right one at a time.”

He is also convinced that despite O’Brien’s praise that he hasn’t yet written a truly great story, illustrating the kinds of swings between extreme confidence and extreme doubt that seem to so often fuel dedicated artists.

(Jane Austen would often disparage her own work as too trivial, and about unimportant things.)

Reading Allan Seager’s papers will disabuse anyone of the notion that even when support for writers was relatively robust, a life as a novelist and short story writer is all about time spent contemplating big ideas about art. There is some of that, but there are also notes about needing to crank something out for one of “the slicks” because the garage roof is leaking, or in one spot, a long lament about what a hack William Faulkner is, and how superior Seager views his own writing.

His book of personal essays, A Frieze of Girls,1 demonstrates a great wit, with tales as funny as anything David Sedaris has produced, but it seems fairly clear that for most of his life Allan Seager was not a happy or contented man. He feud with his sister, my grandmother, kept them estranged for many years until his death, even though they had once been very close.2

He certainly was not content with his station as a writer, even though by any objective measurement he was quite successful, certainly more successful than the grand nephew who every so often writes these pieces to put another reminder into the world that Allan Seager existed.3

One accomplishment I do have over Uncle Allan is that I am fundamentally a contented person. I take no real credit for it, believing it is mostly a function of brain chemistry and being raised in an atmosphere of security and managing to maintain that condition as an independent adult.

There is also something to the fact that I’ve never felt that I had some important genius inside of me that deserves to be recognized. Don’t get me wrong, I have a plenty healthy ego, and I’m not some kind fo Zen master that allows all hardship and strife to roll off me like water off a duck’s back. When it comes to writing creatively, I do aspire to achieve something we’d recognize as “art,” but I do not identify as an “artist” per se.

My three years of graduate school were the one period where I was set-up to live the life of an artist. I lived alone with a desk, a futon, a stereo, and a TV that got only one channel. The sole focus of my time was teaching and writing. I would get home from school, eat lunch, nap for an hour and then write solidly for three without distraction. Around five, my friend Nick would bring his dog, Tallulah over to play with my dog, Sam. We’d let them run in the weedy ballfields across the street from my apartment. Rinse and repeat.

Weekends there might be a party where we would drink and talk about books and writing, not exactly Gertrude Stein’s salon, but not not that either. I wrote the equivalent of a book-length manuscript every year for three years straight, almost none of it publishable.

I look back on that period with great fondness while also having little desire to return. In the abstract, being a capital-N “Novelist” seems kind of awesome, and I periodically experience some frustration that the fiction I have pent up inside will never find an audience, but there’s very few people whose lives I look at and think I might like a trade.

While I dearly wish there was a more robust infrastructure available to support the writing of novels, there is no choice but to adapt. Academia has been a longstanding refuge, but this is breaking down, and if you ask any novelist who also teaches full-time, you will hear lots of frustrations about not having the bandwidth to dedicate to their art.

TV has proved to be the new best patron of the fiction writer. Patrick Sommerville, author of the very fine novel The Cradle, is now much better known as the show runner for the TV adaptation of Station Eleven. Megan Abbott, one of the writers whose books I will read sight unseen, is directly involved with the television adaptations of her books Dare Me, and The Turnout.

Lots of people know David Benioff as the co-showrunner of Game of Thrones, but when I first saw his name in the credits, I was like, huh, that’s the guy who wrote The 25th Hour.

When I say that novels and novelists will always find a way to survive, I don’t intend to be pollyannaish - I think we have to be hugely proactive about protecting the possibilities of people creating art - but that novels and novelists will survive seems, to me, undeniably true.

However, what that survival looks like, and who will have access to those possbilities is very much in doubt. At his newsletter, Experimental History, Adam Mastroianni crunches some numbers and finds that “pop culture has become an oligopoly” and that an increasing share of bestselling books are by authors who have previously had a bestselling book.

This makes obvious logical sense, but if we don’t have an infrastructure and culture that makes space for new entrants and fresh discoveries, we can expect an increasingly homogenized marketplace, which is bad for readers, writers, publishers all.

One part of the solution? This week, try reading a book by someone you’ve never heard of.

Links

In my Chicago Tribune column this week I explore how, even when literary sequels are quite good (as Tom Perrotta’s Tracy Flick Can’t Win is), they can’t help but disappoint.

It’s the Juneteenth holiday, the first time it will be recognized nationwide by the Federal Government. If you’re not familiar with the origins and meaning of the holiday, or if you’re just looking for a a good book, really, I recommend Annette Gordon-Reed’s On Juneteenth.

Anne Trubek noticed something interesting. Every book on the independent bookstore bestseller list this past week has trended on TikTok. I wrote previously about my own exploration of BookTok, including my experience with its most popular writer, Colleen Hoover. As Trubek notes, the homogeneity of the list is concerning. This is the kind of thing that ultimately constrains the types of novels that get written and who becomes a novelist, as originality is undervalued.

Not content to purge books they don’t like from libraries and schools, Republicans in Virginia are seeking to restrict the sale of two books (Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, and A Court of Mist and Fury by Sarah J. Maas) from Barnes & Noble. The upside is that the Streisand Effect, is driving up sales of both books.

A leaked internal memo from Amazon shows they’re worried that their deliberate strategy to churn through workers in order to keep labor costs low and efficiency high may be a problem because they’re running out of people to hire.

Award-winning writer Leila Slimani has provided a list of books for you to “read your way through Paris.”

Esquire has given us a list of the best books of 2022 (so far). My list of best books of 2022 so far will be in next week’s Chicago Tribune.

I don’t know what a “sad girl summer” is, but apparently I’m open to the experience because of this list of 14 “books recommended for a sad girl summer,” I’ve read enjoyed five of them, including Such a Fun Age, by Kiley Reid, Tampa by Alissa Nutting, and Writers & Lovers by Lily King.

Recommendations

I used up all of the unfilled recommendations that I can see in my inbox in my column, so no fresh ones here this week, but if you need something to read, click on any title linked above for a Biblioracle-approved book.

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $134.95 for the year.4

Happy Father’s Day to all who celebrate.

I wonder what the dogs got me.

If you’ve read this far and enjoyed what you read, please consider a paid subscription so continuing this newsletter remains a viable economic proposition.

Take care,

JW

The Biblioracle

Violating my personal, no links to Amazon policy just this once because the book isn’t listed on Bookshop.

There’s an essay in A Frieze of Girls where my grandmother makes an appearance at a college part of Allan’s where he has to warn off his buddies from hitting on her because she’s so beautiful. Very strange to read that.

I’ve long had plans - and even a proposal - to write a book about Allan, but he’s neither obscure enough to count as a discovery, nor famous enough to warrant biographical remembrance.

I’ll match affiliate income up to 5% of annualized revenue for the newsletter, or $500, whichever is larger.