…you must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on. - The Unnameable, Samuel Beckett.

I have been accused of nihilism and it isn’t true, and I want to tell you why.

Maybe this is all self-indulgent, or maybe it’ll be instructive. Tough to tell at this point.

The accuser is the writer Jonathan Malesic, author of (Biblioracle recommended) The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives, wielding a strawman at his newsletter

with a piece titled “Against Liberal Nihilism,” in which I am portrayed as one of the central nihilists.Malesic was writing in response to my response (published in a blog post at Inside Higher Ed) to a New York Times op-ed of his in which he urges students to look at college as an opportunity to do more than earn a credential, and instead see it as, “a unique time in your life to discover just how much your mind can do. Capacities like an ear for poetry, a grasp of geometry or a keen moral imagination may not pay off financially (though you never know), but they are part of who you are. That makes them worth cultivating. Doing so requires a community of teachers and fellow learners. Above all, it requires time—time to allow your mind to branch out, grow and blossom.”

As I said in my response and will repeat here, this is a sentiment with which I couldn’t agree more strongly. This is precisely what college should be.

But, as I argue in my response, for too many students it isn’t, not because they hold a primarily or purely transactional view of college as a route to an employment credential, but because the overwhelming signals our culture and even our colleges send are that the most important aspect of college is the chance to earn a credential.

I think this is bad, as does Malesic, but where I strongly believe the emphasis should be placed on critiquing structures that incentivize this transactional mindset, Malesic’s focus is on urging students to seek out the experiences that will prove transformative, like in his case, watching My Dinner with Andre as part of a professor-led informal discussion group. My view was that Malesic soft-pedaled these profound structural problems to present a soothing narrative for the readers of the New York Times suggesting things will be fine as long as we get kids these days on board with valuing the important stuff.

My interpretation of the import of Malesic’s message is debatable, and I had some very interesting responses suggesting that I was being uncharitable, and that even though the students Malesic is seeking to encourage may not be the primary audience of the Times, the people who do read the paper and agree with the sentiments may be moved to pass on this message. In fact, these people had done just that.

We’re talking not about a disconnect of core values, but a matter of focus and emphasis. There is far more agreement than disagreement here.

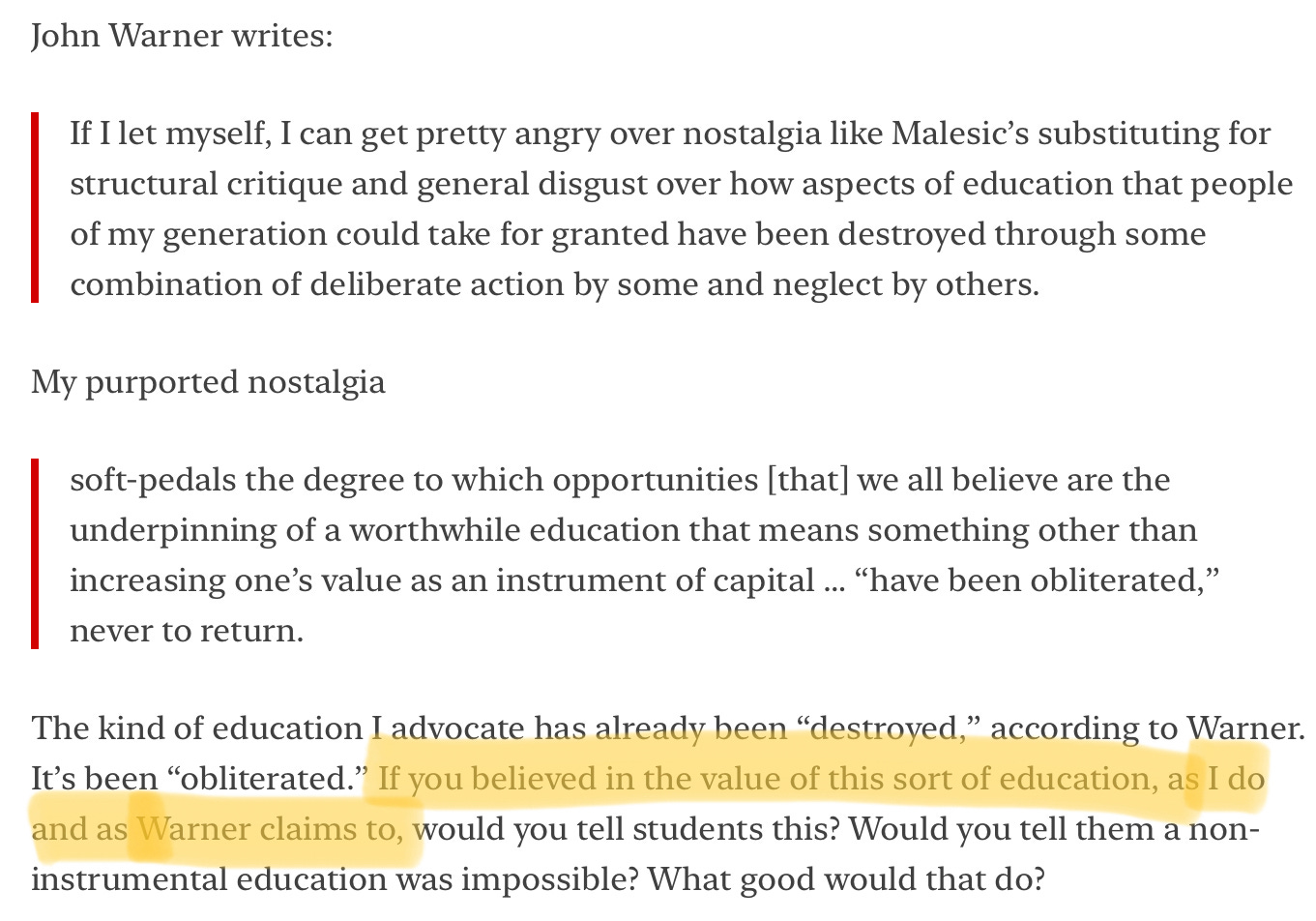

The vast majority of the time I do not get exercised about people disagreeing or challenging something I say, but Malesic engages in a slimy bit of sophistry that had (still has) me seeing red. From his newsletter quoting and responding to me:

That highlighted bit is what set me off, the implication that I may not actually believe what I say about the value of an education as a route to developing one’s whole self. It was particularly galling given the overwhelming evidence of my oeuvre in writing about education. In Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities, I advocate for changing the conditions, for both teachers and students, under which writing is taught so that we can emphasize the essential human aspects of reading and writing, rather than writing to pass standardized tests.

In The Writer’s Practice I provide the blueprint of my own writing curriculum rooted in values of student engagement, exploration, and agency in order to emphasize the fact that writing is an essential tool for thinking and understanding our own humanity, not a mere transaction to please a teacher.

In Sustainable. Resilient. Free.: The Future of Public Higher Education, I lay out a blueprint for how our system of public higher education could (should) be funded and organized in order to reduce the transactional nature of the system and provide students pathways to fully developing their intellectual, social, ethical, (and yes) economic selves.

I’ve written literally more than a million words at Inside Higher Ed calling on institutions to take the needs of students who would like to pursue these higher order experiences seriously, rather than treating them like economic units valued mostly for their tuition revenue.

Some of you are now saying, thou doth protest too much Warner, to which I say, you’re damn right. This shit matters to me and I got more protesting to do.

But you’re also thinking, didn’t you say that the sort of education you favor has been “obliterated”? Sounds a bit nihilistic to me.

Here’s where Malesic has engaged in another rhetorical sleight of hand, implying that the formulations I share in a blog post for a higher education website that is intended for and read almost exclusively by people working within higher education institutions is the same language and presentation I use when interacting with students.

If I was being uncharitable to Malesic’s argument in his original op-ed, he turned around and stuck a shiv in me, and I do not care for it. I also don’t care if this response makes me look oversensitive or petty. (See above: “this shit matters to me.”)

Yes, I do want people working in higher ed to wake up to understand the gravity of the threats to what remains of a chance for humanistic education.

No, I do not tell students that the type of education I favor is “impossible.”

But I do tell students the truth. I tell them that I think they’ve gotten screwed. I tell them about how my tuition all-in for four years was less than $10,000 and you could get B’s galore and still be okay in terms of post-graduate outcomes. I tell them that I had considerable slack to change majors six times, took a bunch of gut courses because I thought they were easy,( but some of which ended up being profound experiences), and very much failed to extract all of the marrow from the bone of my undergraduate degree, education-wise. But also, I tell them the seeds for the dedication that would come in graduate school and beyond were sewn, and those four years were vital to the person I would become (and am still becoming).

I also tell them that the considerably more hostile landscape they’re facing makes grabbing all the experiences they can from college even more important as an act of defiance and resistance to these forces that are aligned against them. I tell them that if there is something going on in my class that could be changed that would help them grab all the experiences they can from college, they should let me know.

I do not assume that what I am offering is a bounty. I ask students if what I’m providing is substantive, and if that seems to not be the case, I adjust accordingly, not by “dumbing down,” but by digging in. Over time, this has led to an approach that is far more rigorous because I’m interested in first stoking engagement, so we can get to the hard stuff.

What it boils down to, I think, is that I am pessimistic about institutions. Malesic is pessimistic about students, at least some students, anyway.

With students, I am ever the optimist, but it’s my willingness to be forthright about what I believe we’re all facing that allows for this optimism.

It does not matter if life is worth living, you’ve gotta just go ahead and live it anyway, so you might as well dig in on the things that matter to you and let the chips fall. In my experience this is a promising ethos to living a contented life, which is the goal, right?

I’m the most day-to-day contented SOB you could imagine, except when I’m exercising my pique on the page. Check that…especially when I’m exercising my pique on the page. Writing this newsletter entry has been quite fun and involving.

Even though I often despair about the state of these things, I do not experience a spiritual malaise, perhaps because I have no belief in the spirit. I am comfortable with the notion that we are here for a time and after that there is a void. So be it.

Or maybe it is simply the good fortune to have been born without a predisposition for depression, something I give thanks for almost daily. I do get angry and upset about things. If asked, I could rattle off the things that I feel are pretty much hopeless (climate, creeping fascism, corporate greed, polarization) but I do not wake up in the mornings and wonder what the point of all this is. I get to my work, which is sometimes writing a self-indulgent defense against a perceived slight that is also maybe proving to be an interesting vehicle for reflection and self-discovery, which hopefully makes it an interesting bit of reading for others.

In a lot of ways, I could be the positive object example for Malesic’s thesis in The End of Burnout that we are not our jobs and society’s metrics of success need not be our own. In the book Malesic writes painfully and movingly about his own disillusionment and even breakdown as he was climbing the tenure track ladder, a position he ultimately left to save himself, a necessary act of bravery to leap towards safety that conventional wisdom would declare as foolhardy. He had become entirely alienated from the spirit that initially animated his desire to work in academia and it left him demoralized, a state from which he has rebuilt himself over time. Obviously, Malesic’s story is not unusual for academia, and for sure extends to realms beyond academia.

Mrs. Biblioracle could tell you some stories about a similar process happening in veterinary medicine.

Perhaps I’ve avoided burnout because I’ve never had a job that was worth wrapping my identity around. I also seem to congenitally lack ambition in terms of external markers of achievement, which is both my greatest asset to being happy and biggest weakness when it comes to reaching higher levels of professional success.

I also think I’ve avoided burnout because I flee from work-related boredom and focus (literally) on figuring out how to look forward to the activities I am going to be tasked with doing on a daily basis.

Additionally, I nap.

Sometimes students would come to me, expressing nascent desires to do the kind of work they perceived me doing. They wanted to go to graduate school, to become a “professor,” to write books. I’ll admit that this was flattering, to be seen as a success, as someone who was engaged with and enjoyed his work, someone whose path was worthy of following.

I did not tell them this was impossible. But I did tell them the truth.

I would explain that I was an “instructor” not a professor, an at-will employee who could be tossed at any time for any or even no reason. I would tell them my salary (never more than $35,000 a year). I would describe how I was able to cobble together a decent living through a number of different gigs, and live better than decent because of not having any student loan debt, being partnered with someone who makes a good living, and also never having children, a choice that was not a sacrifice for us, but would be for many others.

I’d ask these students what interested them about the life of a professor that they perceived and invariably they’d say reading and thinking about subjects of interest to them and maybe making a decent living in the process. I would tell them that a life including those activities kind was entirely within their own power, but it would be very challenging to yoke those interests to a stable, well-paying profession. The odds of becoming a professor were long and growing longer over time, and might require compromises that would leave them alienated from what motivate them in the first place. Pursuing this path and failing to achieve a secure position could leave them tens of thousands of dollars in debt, and also having sacrificed the years they would’ve been positioning themselves for high paying jobs in a non-academic path.

I’d tell them they would wind up in that position and sill not regret their choices because the journey of those 6, 8, or 10 years to a PhD, and what they had learned and experienced in the process may have been worth it.

I would try to reassure them that their deepest selves were not the same as their “job” - Malesic’s message - and it was within their power to live a life of intention, but those intentions may come with compromises (such as their humanistic studies becoming an avocation, rather than their vocation), some of which will seem very unfair, probably because they are unfair.

Once they had managed to carve out a happy niche for themselves, I’d encourage them to never shut up about the unfairnesses and injustices they perceived, even if, especially if they were no longer personally governed by those injustices.

With the possible exception of when I’m defending my honor in a self-indulgent newsletter post, I dedicate the majority of my working hours to making space for more people to experience the kind of education Malesic and I value despite the situation being genuinely hopeless as far as the big picture goes.

Nihilist? Motherfucker, please.

Links

This week in my Chicago Tribune column I have a little fun thinking about the different varieties of book recently released by Peloton instructors Cody Rigsby, Ben Aldis, Emma Lovewell, and Alex Toussaint.

Also at the Chicago Tribune, 75 books to consider for the fall reading season.

Entertainment Weekly has 41 books they think you should consider reading this fall.

Kirkus highlights eight new big fiction books from small presses.

The National Book Awards (which will no longer be hosted by Drew Barrymore because she is a scab, breaking the WGA writers strike) announced its long lists for fiction, nonfiction, poetry, translated literature, and young people’s literature.

ICYMI, on Wednesday, Ilana Masad did some thinking about the craft books writers receive from well-meaning others.

Recommendations

1. Tinkers by Paul Harding

2. The Knife Thrower (And Other Stories) by Steven Millhauser

3. The War Against Cliche: Essays by Martin Amis

4. Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel

5. The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen

Miles P. - Auckland, New Zealand

The turn that Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This makes partway through the book, shedding fresh light on what came before and opening up what comes after still sticks with years after reading it. I think it’s a good fit for Miles.1

Still having a hard time getting people to accept my offer of free books, so untilI can get someone to answer my emails trying to give the earlier ones away, no new ones this week.

My windows are open at home for the first time since May. I’m going to go enjoy some of this day by reading on our porch hammock.

See you next week,

JW

All books linked throughout the newsletter go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and the Teacher Salary Project, which is advocating to establish a federal minimum salary for teachers of $60,000 per year. Affiliate income is $210.30for the year.

I kind of get Malesic's response to you, though. I don't think your response was nihilism, but it does show how referencing structures in a mode that we might call "realism" is a kind of reflex for many of us in response to a call that we find insufficiently critical of the forces and systems that we think are preventing what the caller wants to happen. The problem is that when we invoke realism-about-preexisting-structures too quickly and automatically, we sometimes miss stressing a strong affinity with the person we're reacting to--the scolding correction overrides the possibility of alignment and alliance. And we lose sight of the agency we have, and the agency that the objects of our concern have (students in this case) to make things better even within those constraints, even despite a bleak realism reveals to us. Can I call students to something other than a transactional view of a degree? Only rarely. Can I suggest to them that this should be the way it is, and wait for that to sink in when they look back on their experiences? Yes. Will that delayed reaction lead to something? We can only hope. That's sort of the point of a lot of social and cultural politics: you keep hammering at the powers that be on one hand while also trying to inhabit the world that is possible as much as you can so that if the time comes, lots of us will be ready to step through that door. The realistic-structural point only primes us to hammer at the powers that be; we lose sight of what it is we want if we should happen to break through.

John, your response to Malesic's criticisms, or, perhaps, your simple engagement with the issues, remind me that this discussion is ages old.

In the early 2000s, Phi Beta Kappa ran a series of national symposiums through their affiliated associations asking them to discuss and report back on this resolution: "Phi Beta Kappa should remain gloriously useless." (I was, at the time, a council member for the Delaware Valley Association of PBK, and we hosted the Triennial where this was a central point of discussion.)

That was over two decades ago, and in the time since, numerous books have been written on the value of a liberal education--all were/are attempts to preserve the very things you and Malesic are arguing as valuable in the face of rising numbers of professional degrees that often devalue these more philosophical educational opportunities/classes.

What most concerns me, as a teacher for 30 years, is the manner in which college costs have taken on a "shock and awe" effect: The number of zeros, when all totaled up, shock us into the notion that a degree in Philosophy or English would be a strategic failure when facing a future filled with Stud. Loan payments of thousands of dollars a month .

Look, I am as staunch an advocate for the Liberal Arts as anyone. For almost two decades my "meet the teacher night" presentations have revolved around a description of the 10 goals of a Liberal Education laid out in Prof. William Cronon's essay, "Only Connect." It, James's "On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings" and a few other essays are seminal in my own development as a teacher. But I have to agree with you...sitting down with students to watch "My Dinner with Andre"...? Really? Surely there's an entire thread of discussion about privilege that seems untouched in the disagreement, for good reason I suppose.

Thanks for all your million+ words in so many venues.