When I was in grade school, we were brought into the auditorium collectively to view an animated short film about John Henry, the steel driving man.

I’m assuming most know at least a little about the legend of John Henry, but in short, he was an African-American folk hero known for a race against a steam-powered drill, to see who/what could chisel away more rock to make way for a tunnel for the cross continental trains to pass through. In a superhuman effort, John Henry defeats the steam drill, removing more rock with his mighty hammer than the drill can manage, but in doing so, he drives himself to total exhaustion and death.

The surface level message is something like “you can’t stop progress,” that manpower is awesome, but can only take us so far before machines take the wheel. Of course the roots of the ballad of John Henry in African-American folklore mean there’s far more nuanced interpretations tied to the specific experiences of the community. You can read the ballad of John Henry also as a message that in order to recognized and celebrated, Black Americans must literally work themselves to death. Indeed, there is a condition known as “John Henryism” used by public health researchers to categorize some of the health disparities between Black people and the general population where research found that Blacks who sought to advance their social and economic prospects were more likely to have negative health effects such as high blood pressure, arthritis, and ulcers.

It was a big deal for the entire school to go to see a production in the auditorium during a school day. It would happen for the occasional live performance like a puppet show, and I have a fleeting memory of maybe a troupe of mimes. The only other movie I recall seeing in the auditorium was the animated version of The Hobbit.

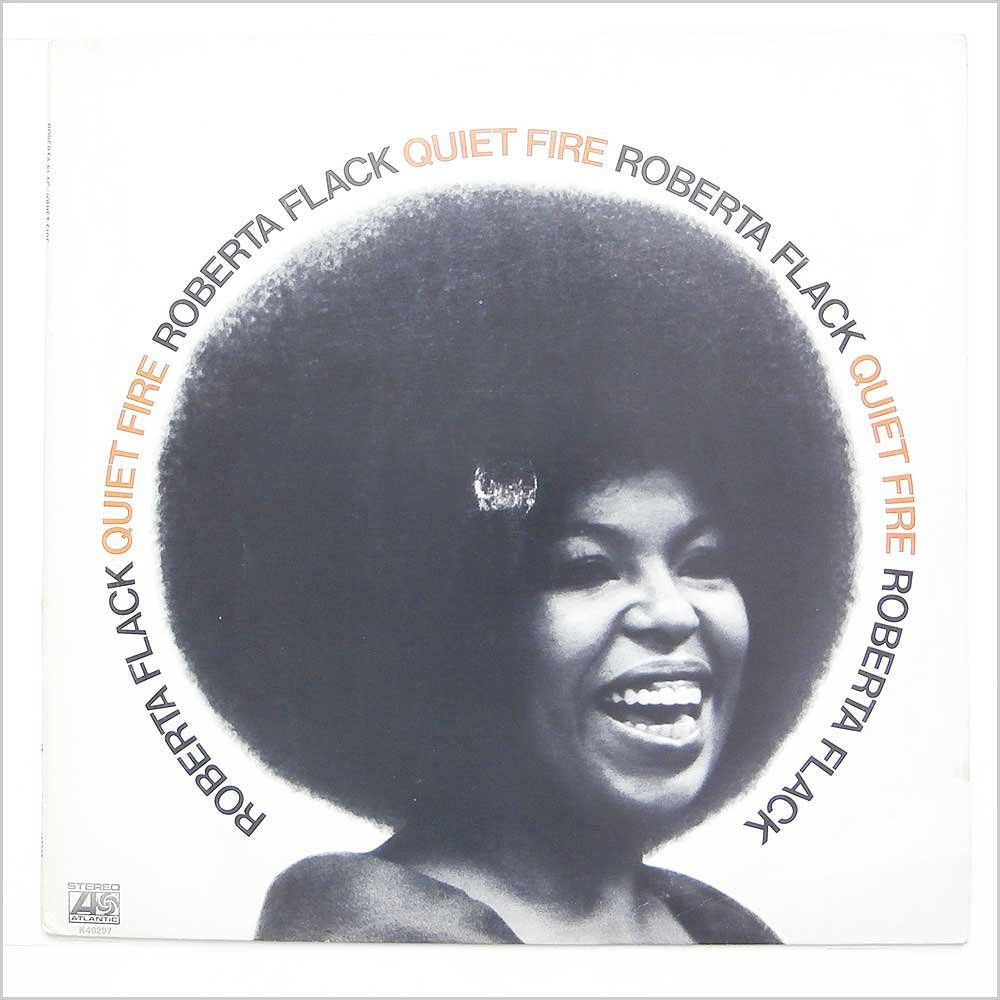

The miracle of the internet allowed me to track down a copy of the video on YouTube, and watching it again for the first time in over 40 years, I’m not surprised I remember it, because it’s really cool. Using an animatic visual style, it tells the story of John Henry through music in a 70’s jazz/soul style, with the lyrics performed by Roberta Flack. I knew Roberta Flack because my parents owned her albums. I can picture the cover for Flack’s Quiet Fire album among my dad’s other soul and R&B records, her striking smile and afro probably being pretty fascinating to a kid from an almost all-white Chicago suburb.

I don’t know that I had a favorite artist in the 1970s, but Flack’s hits were ubiquitous at the time - “Killing Me Softly,” “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” “Feel Like Making Love,” and the song that is, for some reason my favorite, “The Closer I Get to You,” a duet with Donnie Hathaway.

I can only guess at the motivations of the people who chose to expose me and my grade school brethren to an unapologetically African-American story and work of art like this interpretation of the legend of John Henry, but I’m grateful for it. I’m pretty sure it wouldn’t pass muster in Ron DeSantis’s Florida, which is a sad testament about the reversal of progress on that front.

Seeing the film as a kid, I did not care for that surface-level theme one bit. I was upset that John Henry works himself to death. I did not agree that machinery and automation was the equivalent to progress. I do not know why I held these beliefs, where they came from, or why, but I hold them still. It’s possible that the John Henry movie is my origin story for my distrust of technological solutionism for all I know.

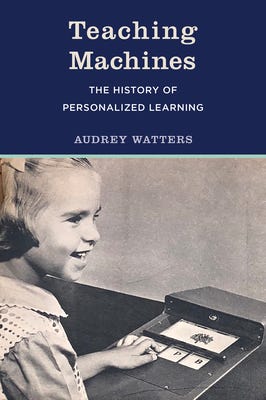

The notion that something is better because it is cheaper, or more efficient, or removes human labor does not sit well with me. Much of this is rooted in my background in teaching where folks promising that teaching machines will either eliminate (or sometimes liberate) teachers dates back to the 1930s. Teaching Machines: The History of Personalized Learning by Audrey Watters tells the story of the men (and it is always men) who believed that they could replace teachers (who are mostly women) with technology.

While Watters’ book is a work of history, it sheds significant light on the present. I reviewed it here, and recommend it highly.

Teaching and learning is an inherently human endeavor, and the notion that a machine, even a very clever and highly sophisticated machine, could do it better than a person is absurd, and yet it is an absurdity that billions of dollars flow towards on an annual basis.

Meanwhile, teachers are subjected to a world that puts them at risk of John Henryism in order to do their jobs and do right by students. It’s absurd.

There is another area dear to my heart that people keep trying to “solve” with technology, but at which they also continue to fail: recommending books.

A New York Times writeup covered some of the recent entrants into the algorithmic book recommending space, including, Tertulia, (a Spanish word meaning “informal salons) and iPhone app which is designed to distill books that are being talked about by people you’re connected to on social media. So, if for example, you were to follow me on Twitter (and you should), and I recommend a book there, it would show up in your Tertulia. Tertulia is essentially sniffing out book-related conversations online and then aggregating that into “books people are talking about.” It will also offer recommendations of what to read based on other people who have read the same books you have, which is the exact mechanism all of the other failed algorithms have tried.

The Tertulia executives explicitly position the app as a Netflix or Spotify for books, which is you know, a good pitch and all, but it overlooks an important truth, at least in terms of the Netflix algorithm: It’s terrible!

I know I am not alone in encountering the Netflix menu, scrolling through the offerings for ten minutes before either settling on a rewatch of something I’ve seen before, or giving up and reading a book instead. To figure out what I want to watch on Netflix, I primarily ask friends who I know have similar taste what they’re watching on Netflix, good, old-fashioned word-of-mouth. It works great.

The Spotify algorithm seems to do better, but this is because movies/TV and music are different mediums, where information like genre, or shared songs in libraries are a much better indication of likely affinity for something previously unknown. Movies and TV shows have more moving parts that may go into what draws the audience to them, and books are more complex still.

Listening to a song is also a commitment of a few minutes and can require minimal attention. Movies are a couple of hours of your time, and books even more than that.

With books, there is no real substitute for a recommendation that comes from a human. Consider the extreme proliferation of celebrity book clubs and the significant influence those clubs have had on sales. Even Jenna Bush - no Reese Witherspoon (no offense, Jenna) - can move units through her “Jenna Reads” club.

But as the purveyors of these apps know, it is difficult for human recommendations to work “at scale.” There’s only so many books a single person can be familiar with, and only so many people they can offer recommendations to without becoming something like John Henry battling the steam drill.

I know this because I experienced it at the origins of The Biblioracle. The first appearance of The Biblioracle occurred in the comments on one of the matchups at the Tournament of Books when Kevin Guilfoile and I didn’t have much of anything interesting to say that day. As a lark, I said that anyone who posted the last five books they read in the comments could get a custom book recommendation from me. At the time, we would get maybe 60 or 70 comments on a matchup at most, so I didn’t think it would be all that burdensome.

I recommended over 300 books that day. A couple of additional times The Morning News opened a live Biblioracle where people could post their lists of recent reads and get a recommendation. I think the first one was two hours long and I had over 500 requests. By the last one, we narrowed it to 30 minutes and I still couldn’t keep up without my brain turning to mush.

By the end of a live session, I would wrack my brain for the name of a single book, any book, and come up empty. It didn’t help that I swore I would not repeat a recommendation in a single session.

There’s no business model that supports person-generated custom book recommendations as a discrete proposition, which is fine because people recommending books to each other as part of the natural conversation about books works pretty well already.

So far the recommendation requests here haven’t been at all overwhelming for a couple of reasons. One is that the audience isn’t all that big. Another is that my hunch is that the audience that is here generally already has more books than they can handle lined up to read. This is not a cohort that often needs a recommendation.

It’s not that I’m rooting against any of these apps - the more book conversation the better, as far as I’m concerned - but I am skeptical that any of them can achieve the goal they’re setting for themselves.

The field is littered with failed attempts at a Netflix for books, and as Netflix’s prospects look increasingly grim, you wonder if it’s even a desirable goal in the first place.

In fact, many of Netflix’s current problems look to me like ones which plague the publishing industry, producing more product than you can successfully promote as many significant projects appear on the platform, only to sink without a trace having not caught the attention of the platform’s algorithm.

Netflix might need a Netflix for Netflix.

Links

My Chicago Tribune column this week is about a viral TikTok phenomenon that had readers sharing tips for getting “free” Amazon e-books. Only problem is that it’s ripping off independent authors.

Barnes & Noble has announced their “best books of 2022 (so far), including Emily St. John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility, which would definitely be on The Biblioracle’s best books of 2022 (so far) list.

The campaign by reactionaries to censor culture they don’t like has reached increasingly absurd heights, including this movement to “hide the pride” which instructs people to check out any book celebrating Pride Month so it is removed from public display.

LitHub has “35 books you need to read this summer” including one I’ve already read and highly recommend, Teddy Wayne’s The Great Man Theory, and another I’ll be reading for sure, Hurricane Girl by Marcy Dermansky. As for the 33 others? Time will tell.

Recommendations

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $132.15 for the year.1

1. Diary of a Film by Niven Govinden

2. The Quest for Corvo by A.J.A. Symons

3. Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh

4. Mantel Pieces by Hilary Mantel

5. The War of the Poor by Eric Vuillard

Dan J. - London, UK

I know this isn’t important in terms of what I pick, but I’m sitting here jealous that Hillary Mantel has a last name that can be used as a pun in a book title. I think Dan will enjoy the psychological intrigue and simmering wit on John Banville’s The Book of Evidence.

1. Flights by Olga Tokarczuk

2. Divorcing by Susan Taubes

3. Transient Desires (Commissario Brunetti #30) by Donna Leon

4. There Are No Accidents by Jessie Singer

5. The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante

Emma K. - Luxemborg (by way of Washington D.C.)

I’m actually not sure how much I “liked” this book, but it has stuck with me in a way that makes me think liking it wasn’t necessarily the point, which is pretty interesting to think about. I’ll be curious to see what Emma makes of Crudo by Olivia Laing.

I’ll be starting a new book today. Choosing between Dan Chaon’s Sleep Walk and Alison Espach’s Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance.

See you next week, and the week after that, and after that…

John

The Biblioracle

I’ll match affiliate income up to 5% of annualized revenue for the newsletter, or $500, whichever is larger.

"Another is that my hunch is that the audience that is here generally already has more books than they can handle lined up to read" - Bingo!

"With books, there is no real substitute for a recommendation that comes from a human." - For this reason, I always enjoy looking through annotated bibliographies or Acknowledgements pages or 'For Further Reading' lists.

Even a casual reference -- "I’ll be starting a new book today." -- is a wonderful occasion for serendipity. In the promotional copy on the Bookshop page of "Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance", for example, nearly a dozen other books are mentioned by way of comparison. Those, and their authors' other works, could make up at least a couple of hours of follow up exploration. Endless opportunities; who could be bored?

Hi John! I'm curious about how you come up with your recommendations. Is it intuitive? Or do you have a set criteria you use? And why the last five books a reader has read--how did you come up with that structure?