Note: Yet again I have rambled on beyond the limits of some email programs. To make sure you see the whole post, please click through to the version housed on the web.

This past week saw a small online kerfuffle over the disappearance of cursive writing.

I have some thoughts, but first, to the kerfuffle.

It starts with an article by former president of Harvard University, Drew Gilpin Faust, writing in The Atlantic about her discovery that “Gen Z Never Learned Cursive.”

You can tell starting a kerfuffle was the goal of the editors at The Atlantic by that choice of article title, especially compared to the title chosen for the print edition, “Cursive Is History.”

“Gen Z Never Learned Cursive” primes the audience for one of those inter-generational moral panic pieces: KIDZ THEESE DAZE CANT EVEN RITE GOOD.

While there is some degree of superiority and condescension in Dr. Faust’s piece - Kids can’t even read a cursive thank you note! - it is more of a lament than a call to arms to restore cursive to the curriculum.

It is written in a register that I personally find grating, the professorial sage doing some deep sighing over being prevented from sharing the full flower of her wisdom with her young charges because societal and cultural change has rendered what was once meaningful shared experience - in this case, reading old manuscripts - obsolete.

It also ends with a just-so kicker that caused my “that didn’t actually happen” editorial radar to sound the alarm.

Writing (literally handwriting) at his newsletter, Tom Scocca identifies Faust’s essay for what it is, elite preening that misses important historical and cultural context. As Scocca points out, the need for cursive as opposed to block printing was rooted in the limited technology of the quill and ink pen, in order to avoid huge blobs of ink staining the page. The rise of the ballpoint did more to undermine cursive than any subsequent technology because the form of cursive was now divorced from its utility as a tool for communication.

For sure, some folks will say that they write faster in cursive, that it is more efficient than block printing, but this is entirely an artifact of 1. Spending many more hours practicing cursive during schooling, and 2. Personal idiosyncratic preference. There is nothing inherently superior about cursive as a writing style when it comes to speed or even legibility.

If speed was the goal of handwriting instruction, we all should have been taught shorthand, or been trained on court transcription machines. The instruction of cursive, instruction which consumed many hours of the early years of my schooling, is rooted solely in a kind of unthinking tradition.

You are probably detecting that a significant part of my enmity for cursive is because throughout grade school it was the bane of my existence.

Handwriting: “Needs Improvement”

I don’t know how much of this story is true, how much is family apocrypha, and how much is me latching onto a personal origin story that makes sense to me, but when I went for pre-Kindergarten testing, there were concerns about my lack of fine motor coordination. I couldn’t color in the lines, or cut out shapes from construction paper. My version of the Thanksgiving turkey drawing you make by tracing your hand so the thumb is the head and the fingers the Turkey feathers looked maimed or mutated.

As I understand it, there was some discussion about holding me back from the start of school so I could ripen a bit more, but then my mom pulled out a book and asked if it mattered that I could already read.

I knew my ABCs backwards and forwards, but I could not write those letters in cursive to save my life. My report cards in the early years were generally sterling, with one black mark, “Handwriting: Needs Improvement.”

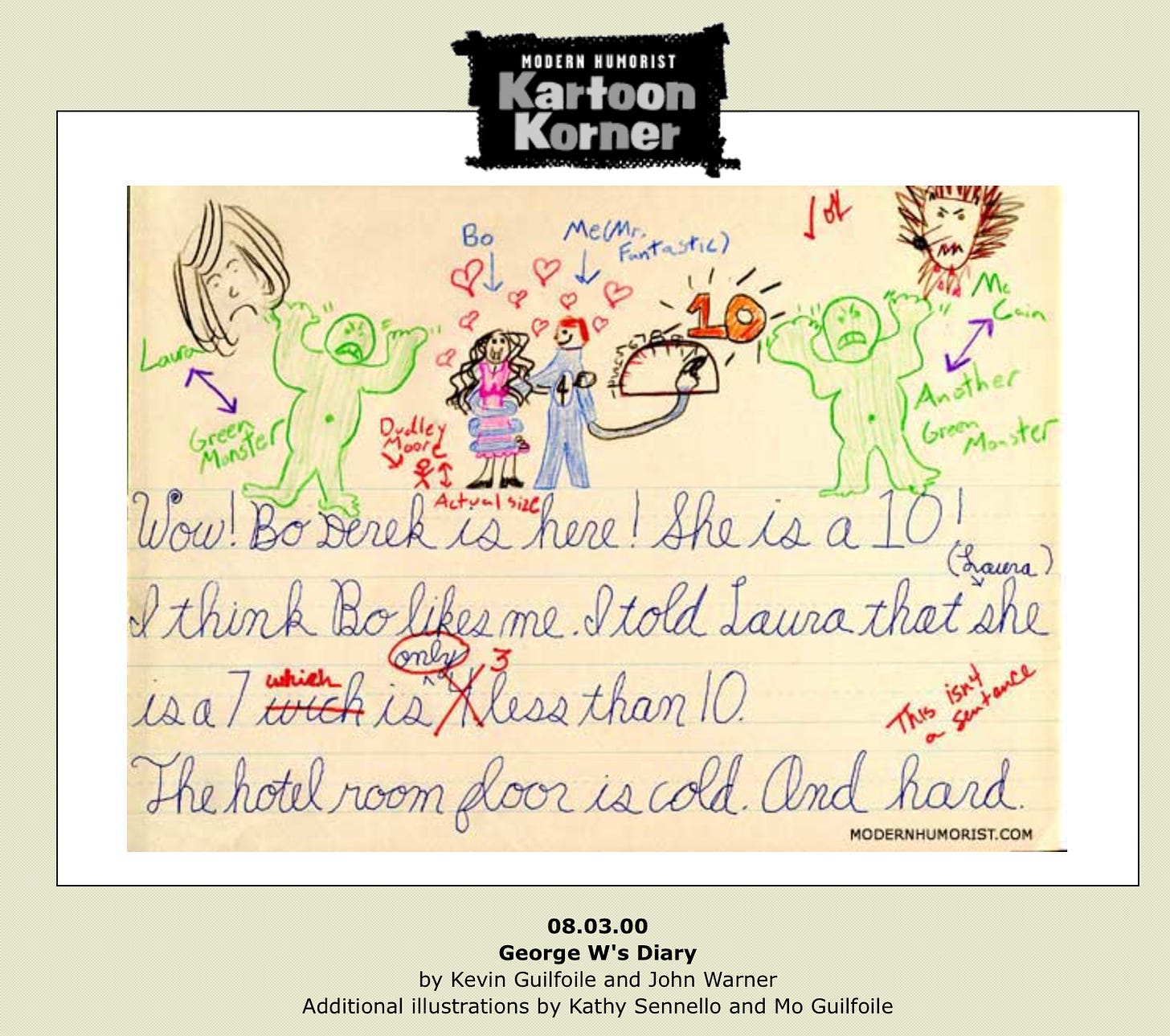

My handwriting never really improved and was so bad that when Kevin Guilfoile and I first conceived the convention diary of George W. Bush written in the style of a 2nd grader’s school journal entries (which would eventually evolve into our book My First Presidentiary), for the Modern Humorist website, on the days I was responsible for the material, I had to have Mrs. Biblioracle do all the handwriting. At age 30 I could not write cursive well enough to pass for a slightly dim grade schooler.

To write by hand at the speed of my thoughts meant near total illegibility. Teacher after teacher would ding my class essays because they could not interpret my writing. The kind ones would ask my what I’d said and sometimes rescind the penalty. Others would simply equate my inability to write in cursive with an inability to write.

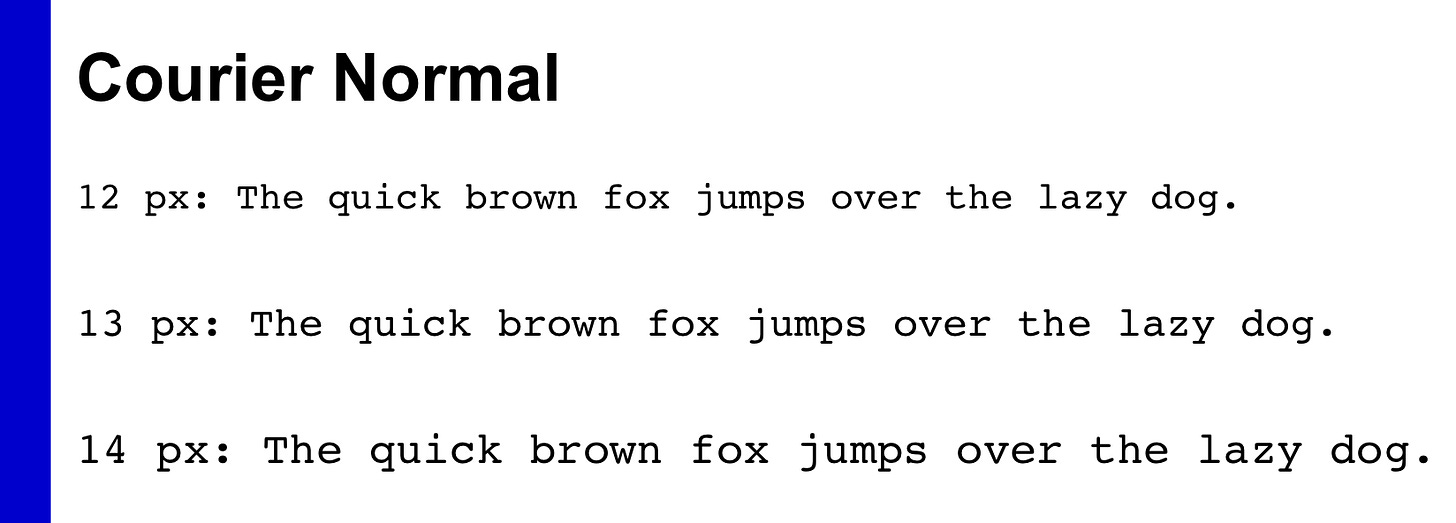

In summer school in fifth grade, I took my first typing class, hammering out my quick brown foxes jumping over the lazy dogs on an old Royal manual. Those glimmers of hope were fanned into a flame by the arrival of an Apple IIe personal computer by eighth grade, and in college, a Brother personal word processor, followed by a Mac SE-20 with a dot matrix printer junior year.

At last, finally, I could write.

Handwriting and the fallacy of education folklore

Some of you are possibly horrified. You possess a nice, flowing script that brings you pleasure to produce. Seeing the chicken scratch of others is an assault to your senses and you don’t understand why students can’t learn this “basic” skill.

Handwriting is personal - literally a signature - and perhaps you even agree with Faust’s contention that “The inability to read handwriting deprives society of direct access to its own past.”

I do not say this to be harsh, but you are wrong. Clinging to a practice because it is what we once learned, or what what done to us is no better than superstition, and these superstitions are often invoked in ways that result in harming children’s educations.

I am not unsympathetic to this mindset. Superstition rooted in our own pasts can be very very powerful and quite persuasive, even in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Consider a practice like the number of spaces after a period. Because I learned to type on a Royal manual typewriter which used the non-proportional Courier font, where every letter is an identical width, I too learned to use two spaces after ending punctuation in order to signal a new sentence.

But perhaps you’ve noticed that everything you now read (with some very specialized exceptions) is formatted with a single space after a period…period. This is because we now write using word processing software using fonts where each letter has a proportional width, and which automatically adjusts the distance between characters (known as kerning) to create maximum readability.

(Some of you are going to be tempted to trot out a 2018 study that seems to indicate - on the basis of a very small sample - that two spaces after a period allows subjects to read slightly more quickly, but the study was conducted with a monospace font, leaving it immaterial to the typefaces that most of us actually read on a day-to-day basis.)

On a more substantive front, think about the spanking of children. At this point, there is overwhelming evidence that spanking is an ineffective tool of child discipline, at best having no long term impacts, while having the potential to do great harm. There is no affirmatively good reason to spank a child.

But I was spanked, and I turned out okay. Better than okay! I probably even “deserved” it most of the time. Doesn’t that mean that spanking is an essential tool for proper child rearing?

Well…no. This is classic hindsight bias. It’s just as, (actually more), likely that I turned out fine despite being spanked, rather than because of being spanked.

This kind of bias is endemic in our educational practices, and explains why I was drilled for hours and hours on cursive in the 1970s and 80s, well past the time when cursive was a necessity for effective written communication.

It’s also why I was subjected to direct grammar instruction, including sentence diagramming, all the way through high school, even though there is no evidence linking sentence diagramming or direct grammar instruction to writing proficiency, something that was shown by Lou LaBrant in the 1950s!

You will read many defenses of sentence diagramming or direct grammar instruction as keys to learning how to write, but this is simply not the case. Writing as a cognitive activity is not related to being able to name the parts of speech, or to then represent them visually through a diagram.

(Contemporary defenses of sentence diagramming that get past nostalgia often talk about visual or kinesthetic learners benefitting from diagramming, but the notion that there are different “learning styles” for different students is itself a myth with no evidence so support it.)

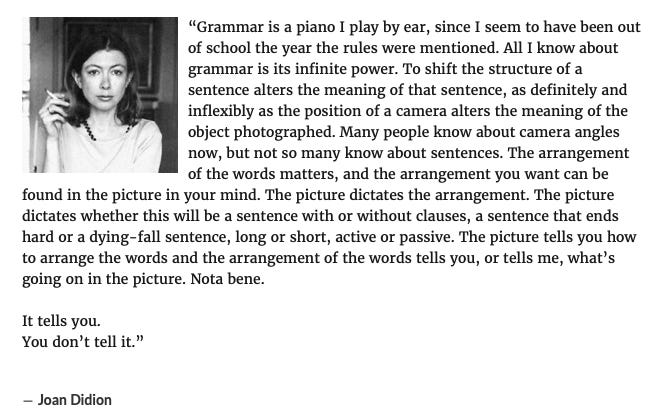

Writers don’t need to learn the rules of formal grammar. They need to practice making sentences, sentences that satisfy the demands of the rhetorical situation and create a productive and pleasing experience for the audience.

Joan Didion got it:

You can actually get students who are very early on in the development of their writing practices to think and act like Joan Didion and focus on making sentences, rather than worrying about “correct” grammar. “Correctness” is not a value we actually associate with the writing we connect with as audiences.

Once you start going down the rabbit hole and examine many of the educational practices you’ve been subjected to - or in my case those which I also visited upon my students - you start to realize that there is almost nothing of substance underpinning them

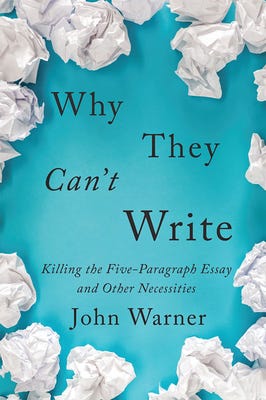

As you can probably tell from my tone, I find this hugely frustrating. Those frustrations are what drove me to write Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities. Putting aside my humble midwestern nature for just a moment, the book is utterly correct, that is if the goal of writing instruction in school is to help students learn to express themselves in writing.

But this isn’t really the goal of writing instruction in school, which is why so many young people do not like writing. As I found out once I was given access to a machine that allowed me to capture my thoughts, writing is fundamentally a tool to achieve self-knowledge and a liberated mind.

But self-knowledge and a liberated mind can be unpredictable, even dangerous in school contexts, so instead, we put students through a rote curriculum, the equivalent of drilling on cursive writing.

The writing most students are asked to do in school lacks any inherent interest, and because of that is extremely low in terms of rigor, as the assessment can be satisfied by thoughtlessly employing a template and following a bunch of “rules” (number of paragraphs, thesis at the end of the first paragraph, start the conclusion with “in conclusion”) that don’t actually exist in the real world.

I don’t get it. I don’t know why we do so many things that separate young people from the pleasures of learning. I mean, I do know why, but I feel like it should be easier to break through the folklore of the past and discard the practices that are not rooted in the values we claim are important.

And yes, the way students are taught math now is superior, even though it’s totally confusing to those of us who learned under a different method. It’s confusing, it’s frustrating, and it seems “wrong,” but it isn’t.

Links

My Chicago Tribune column the week is on Adam Langer’s Cyclorama, a novel particularly attuned to the Chicago area I grew up in. It’s the seedy underbelly of of John Hughes’ suburbia.

Entertainment Weekly has a fall books preview, as we enter the season of far too many desirable titles being released simultaneously.

It’s Banned Books Week, and a new report from PEN America shows how dire things are when it comes to people trying to ban books. It’s so bad that I after deciding not to publish anything about Banned Books Week during Banned Books Week, I ended up writing next week’s column about banned books.

Really fascinating piece by Vanessa Angelica Villareal at Harper’s Bazaar looking at the recent “controversies” around casting non-white actors in fantasy shows, and how race has always been integral to fantasy storytelling.

While I maintain plenty of love for the classic books I read in my youth, as you might be able to tell from today’s newsletter, I’m also a fan of making room for “new classics.”

Speaking of classics, and being a child of the 70s, I can very much appreciate this rundown of “the essential Judy Blume.”

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $229.50 for the year.1

1. The Midnight Library by Matt Haigh

2. The Dearly Beloved by Cara Wall

3. Swimming Back to Trout River by Linda Rui Feng

4. The Next Great Migration by Sonia Shah

5. The Water Knife by Paolo Bacigalupi

Dea P.

I’m going to lean into the climate fiction on the list and recommend a book that feels increasingly prescient, even though it was published 30 years ago, Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler.

My apologies for being cranky about things this week. Sometimes the world just makes you cranky.

I hope everyone has a cranky-free rest of the day, unless you genuinely enjoy feeling cranky, which I probably do sometimes.

If you’ve been enjoying this newsletter, please consider a paid subscription.

JW

The Biblioracle

I’ll match affiliate income up to 5% of annualized revenue for the newsletter, or $500, whichever is larger.

“The inability to read handwriting deprives society of direct access to its own past" ". . . you are wrong”

Actually, Faust is right about this. There's a difference between being able to WRITE in cursive, and being able to READ it. Historians study paleography for a reason.

I really enjoyed reading this. I, too, learned to write on a typewriter and find it difficult to break the habit of putting two spaces between sentences. (See?) However, until reading this I couldn't remember why!