This is one of those weeks when two seemingly disparate notions keep knocking around my brain at the same time, which usually means some part of my subconscious thinks they’re related.

How Republican nominee for U.S. Senator from Ohio, J.D. Vance, first came to prominence through a book.

Let’s see if my subconscious is right.

Roger Angell published his first piece in the New Yorker 1944, his last in 2020, and was most known as a chronicler of baseball, including classic collections of essays, The Summer Game, and Season Ticket.

He is the product of a time when American literary culture covered a few Manhattan blocks, and the gatekeepers could’ve gathered at a mid-sized dinner party. His mother, Katherine Sergeant Angell White, was one of the earliest editors of the New Yorker. Angell’s stepfather was E.B. White, he of Charlotte’s Web and The Elements of Style (among many other things) fame.

I suppose we could say that Angell was the benefit of nepotism, a twenty-four year-old getting his short story published in the New Yorker because his mom works there, but his accomplishments long outstripped any concerns that the leg up might’ve been undeserved.

In a remembrance, New Yorker editor David Remnick walks through Angell’s very interesting life, and captures the spirit that made Angell’s work come alive for so many, the apparent joy and endless fascination he took in observing the American pastime. He wrote about the actual sport of baseball, not baseball as metaphor for something else in an attempt to elevate its station, which is much harder to do than you would think.

Angell, Roger Kahn (Boys of Summer), and George Plimpton (Paper Lion, Open Net) were the writers on sports I read as a kid that introduced me to characters who played long before I was born, but who are captured for audiences forever thanks to them.

Like Angell, Plimpton was part of the literary noblesse oblige, longtime editor (and financial supporter) of the Paris Review, launcher of many literary careers in his own right.

Angell is perhaps the last member of the time when American literary culture was a kind of club, where concerns of commerce and profit were secondary to the notion that good writing was important to put in the world.

All those literary imprints that are now rolled up underneath much larger conglomerates (Knopf, Dutton, Simon & Schuster, etc…) were once just rich white people who could’ve decided to do other stuff with their money if getting wealthier or accruing power was their chief goal.

It’s important not to overly romanticize those earlier times. All that obligeing by those noblessers was not exactly inviting to those of different and diverse backgrounds. Publishing has never been a meritocracy.

But it’s impossible to look at the life Angell lived and the work he produced and not see a man of merit, and not only for the quality of his writing.

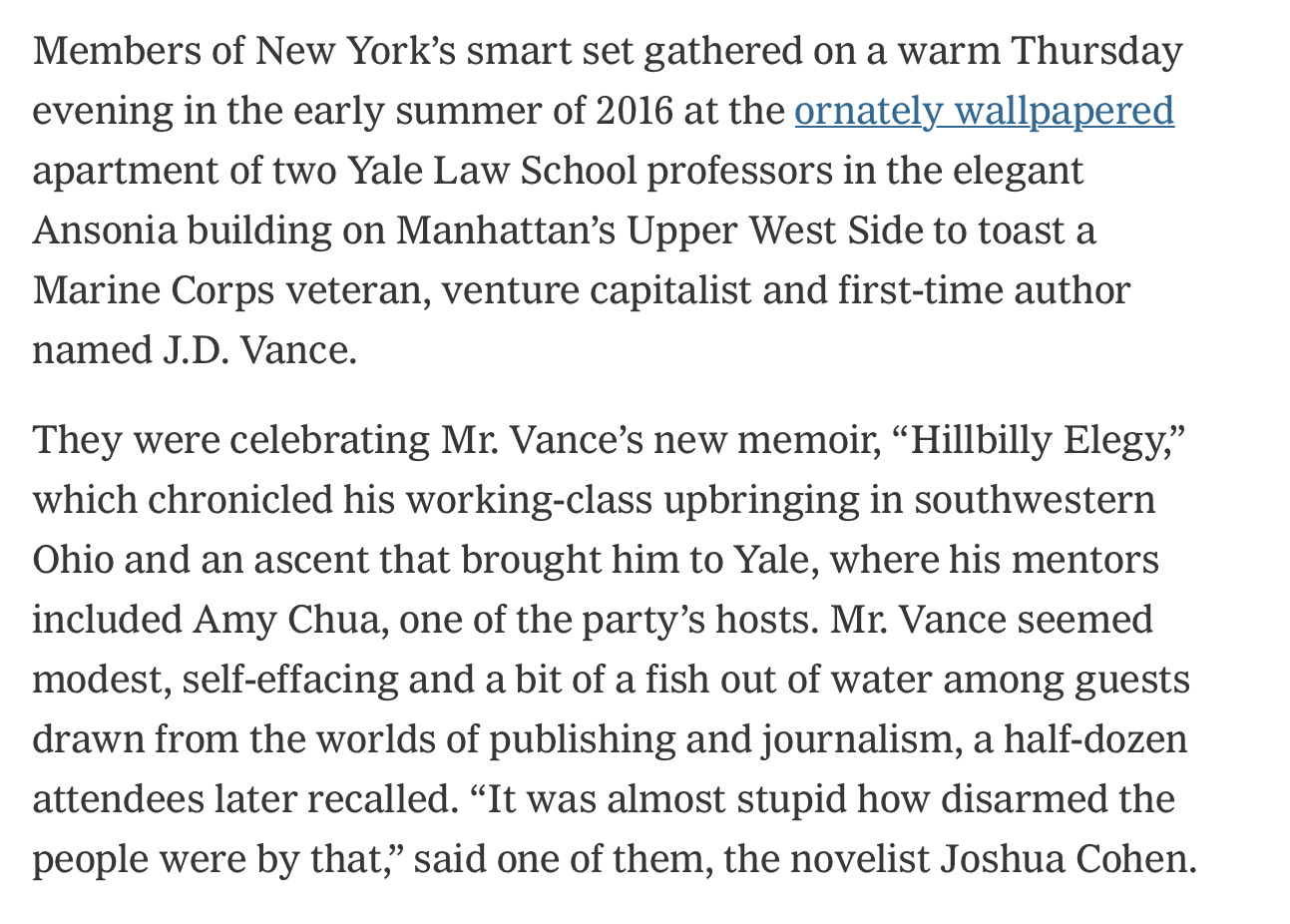

And then we have J.D. Vance, recent victor in the Republican U.S. Senate primary in Ohio. Vance first came to prominence as the author of Hillbilly Elegy, the story of his upbringing in the rural part of his state. Vance shares the multi-generational saga of his people striving for middle class security, but being undone by poverty, addiction, and a country that no longer cares about the white working class.

After a stint in the U.S. Marine Corps, Vance attended Yale Law School, where his professor/mentor, Amy Chua urged him to write about his upbringing. Chua was a bestselling author herself, most known for Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, her book on her decision to raise her daughters “the Chinese way.”

Chua is an American success story, a first-generation daughter of immigrants who rose to professor of law at Yale, and one-half (the more prominent half) of a law school power couple with her husband Jed Rubenfeld.

After looking at some passages that Vance had written, Chua introduced Vance to her literary agent, after which, in Vance’s words, it was “off and running.”

The story of Vance’s rise to prominence could have been cheering, an exemplar of the opening of opportunity beyond those born into access to important institutions.

But of course Vance is an absolute horror. A man willing to engage in whatever debasements may be necessary in order to achieve power, and a committed believer in racist white supremacy, the same ideology that drove the terrorist who murdered 10 people in a Buffalo supermarket. Vance practically makes Ted Cruz look principled.

As Marc Tracy wrote recently at the New York Times, we very much have New York publishing (and Hollywood) to thank for Vance’s rise to prominence. Tracy’s story opens with a scene at a publishing party hosted by Chua, feting the release of Hillbilly Elegy.

The novelist Joshua Cohen at the end is now Pulitzer-prizewinning novelist Joshua Cohen. It’s interesting how eager putative liberals were to embrace Vance’s narrative about the region, and now how many of them wonder what happened to the nice young man from Yale, but if you read correctives to Vance’s mythology, like Elizabeth Catte’s What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, you’ll see that Vance is pretty much what he’s always been, a man willing to tell a story that flatters the people who can give him a leg up. Earlier, that was Amy Chua. Now it’s Donald Trump.

Amy Chua is not Donald Trump, but the rise of J.D. Vance is an illustration of what it means when individuals become gatekeepers, and use that power to elevate other individuals, as opposed to establish more equitable systems. She is famously influential when it comes to placing Yale law students into important judicial clerkships, including reportedly counseling women interested in working in (then appellate judge) Brett Kavanaugh’s chambers to project a “model-like femininity.” (Chua denies saying this.)

When Kavanaugh was nominated to the Supreme Court, Chua published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal lauding him as a “mentor to women,” including her own daughter, who would go on to clerk for Kavanaugh at the Court.

This mentor to women is widely considered to be the deciding vote that will end the federal right for women’s bodily autonomy.

Chua and Rubenfeld have become polarizing figures on the Yale Law campus. Rubenfeld was suspended from certain activities after an institutional inquiry into charges of sexual harassment. Chua has been accused of playing favorites when it comes to clerkships and other perks. There’s been a recent push to resurrect her reputation with others claiming she’d been unfairly targeted.

I don’t know what the truth is other than as a culture, we are no better off with professors at Yale Law having such a central role in who gains access to power than when this kind of influence was confined to a handful of addresses in New York City.

Roger Angell is universally described as a “gentleman,” a person careful with his words and his work, someone dedicated to ferreting out truths that he can share with the wider world.

Vance and Chua seem driven by attention, fame, and power. They both have “good stories to tell,” but telling those stories must mean more than achieving those things.

Right? Or maybe not. Maybe the acquisition of influence and then the ability to assert that influence on the behalf of others in your club is the inevitable consequence of the society as we’ve arranged it. Maybe the whole notion of having “guardians for the culture” is simply outdated or even wrong, that there is no space for guardians, or that we should be suspicious of any guardians, wherever they may come from.1

As usual, no answers here, only questions, which is probably why my subconscious put these notions together in my head.

Maybe others have more and deeper insights than I’m able to manage about these phenomena.

Links

My Chicago Tribune column this week is about the old Yes & Know, magic pen/invisible ink books that were the great pacifier of kids on long car rides in the era before digital devices. Surely I can’t be the only person who remembers them.

The Christian Science Monitor tells us the 10 books from May that we should invite into our homes.

The drive from some conservatives to censor books has reached an even more dangerous phase in Virginia where right wing Republicans have filed a suit against a Barnes & Noble for stocking the book Gender Queer, because it is “obscene” and should not be made available to minors. Scary stuff.

The literary journal The Believer was briefly owned by a sex toy website. It’s now back in the hands of the original owners at McSweeney’s.

The New York Times has 6 audiobooks to listen to this month.

Recommendations

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $110.05 for the year.2

1. Geek Love by Katherine Dunn

2. Election by Tom Perrotta

3. Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell

4. Luster by Raven Leilani

5. Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

Lila P. - Kansas City, KS

Brooklyn by Colm Toibin is on of those satisfying reads where you root for good things to happen to the good characters.

As always, the content of this newsletter will be freely available to all, which is why paid subscribers are especially important, as they make ongoing access for all, and my ability to continue to do the work sustainable. If you’ve enjoyed the newsletter, please consider supporting it this way.

Not even Memorial Day and many of us are experiencing a major heat wave. A good reason to stay inside with a good book.

Until next week,

JW

The Biblioracle

J.D. Vance’s campaign has been financed by billionaire Peter Thiel who is not really a fan of democracy, or the First Amendment, having backed Hulk Hogan’s lawsuit that bankrupted Gawker.com, out of spite for previous Gawker coverage of Thiel.

I’ll match affiliate income up to 5% of annualized revenue for the newsletter, or $500, whichever is larger.

When Hillbilly Elegy was first published, I immediately bought the book. I thought it was a very compelling read, and in my mind, congratulated J.D. for overcoming a very difficult upbringing and getting a first-rate education. But now, he has done a 180, embracing the worst president EVER. If I had known then what I know now about him, I NEVER would have bought his book. I was duped - I thought Vance had integrity. I was so wrong. He sold his soul to the devil.