ChatGPT Can't Kill Anything Worth Preserving

If an algorithm is the death of high school English, maybe that's an okay thing.

It’s not every week that someone with my particular employment profile and expertise has something they’re knowledgable about become a hot topic of national discussion, but the release of OpenAI’s, ChatGPT interface generated a sudden flurry of discussion about how we teach students to write in school, which is something I know a lot about.

I’m never sure how much overlap there is for the various audiences that consist of the John Warner Writer Experience Universe, but while to folks here I am, “The Biblioracle,” book recommender par excellence, to a whole other group I am the author of Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities, and The Writer’s Practice: Building Confidence in Your Nonfiction Writing, and a blogger about education issues at Inside Higher Ed.

Modesty aside, and somewhat to my surprise, I have become an expert in how we teach writing. That expertise was birthed from the frustration I experienced in trying to teach writing to first-year college students over the years, and finding them increasingly disoriented by what I was asking them to do, as though there was no continuity between what they’d experienced prior to college, and what was expected of them in college.

These were well-above average students at selective schools (University of Illinois, Virginia Tech, Clemson), who did not necessarily lack writing skill, but had very negative attitudes towards writing. To cut to the chase, and to keep from repeating everything I cover in Why They Can’t Write, rather than having students wrestle with the demands of trying to express themselves inside a genuine rhetorical situation (message/audience/purpose), they were instead producing writing-related simulations, utilizing prescriptive rules and templates (like the five-paragraph essay format), which passed muster on standardized tests, but did not prepare them for the demands of writing in college contexts.

My books are a call to change how we approach teaching writing at both a systemic and pedagogical level. What teachers and schools ask students to do is not great, but that asking is bound up with the systems in which it happens, where teachers have too many students, or where grades or the score on an AP test are more important than actually learning stuff. It’s not just that we need to change how and what we teach. We have to fundamentally alter the spaces in which this teaching happens.

It is difficult to overstate how bad things have been for a couple of generations of students. This tweet from the writer Lauren Groff (Matrix), lamenting what school had done to her son’s attitudes towards writing is a not uncommon testimony I hear from parents and students alike.

Deep down, this is a question about what we value, in what we read, what we write, and unfortunately, we have attached a set of values to student writing that are disconnected from anything we actually value about what we read, and what we write.

Along with many others, I’ve been shouting about these problems for years, often into what felt like a void, but this past week, once people had a chance to see what the ChatGPT could produce, suddenly attention was being paid.

It’s important to understand what ChatGPT is, as well as what it can do. ChatGPT is a Large Language Model (LLM) that is trained on a set of data to respond to questions in natural language. The algorithm does not “know” anything. All it can do is assemble patterns according to other patterns it has seen when prompted by a request. It is not programmed with the rules of grammar. It does not sort, or evaluate the content. It does not “read”; it does not write. It is, at its core, a bullshitter. You give it a prompt and it responds with a bunch of words that may or may not be responsive and accurate to the prompt, but which will be written in fluent English syntax.

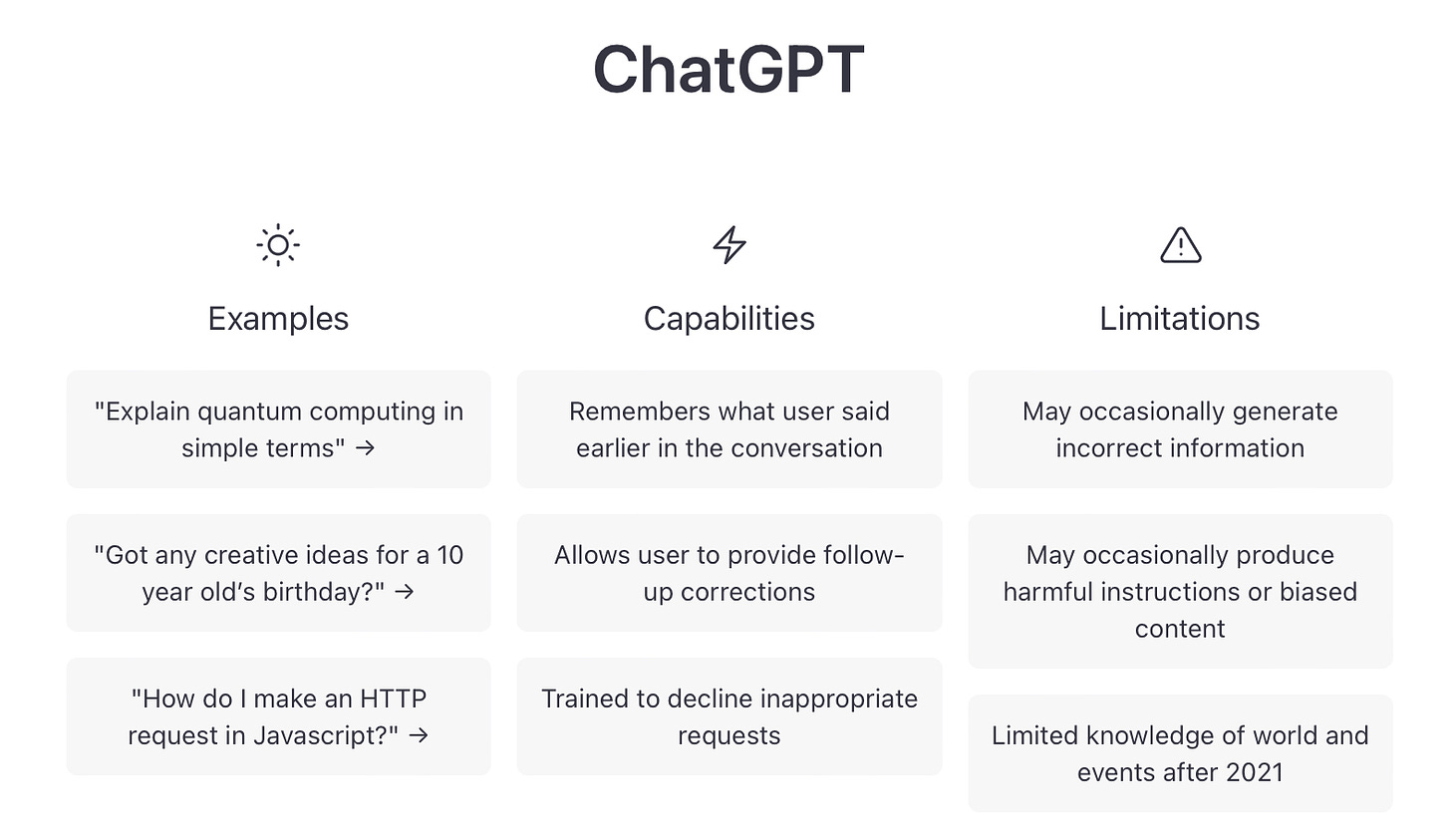

This snapshot from the ChatGPT homepage is a good overview of what OpenAI says ChatGPT can do.

I first wrote about the underlying algorithm (GPT3) at Inside Higher Ed back in March 2021, when it was put to the task of trying to answer some college-level writing assignments and then compared to the output of human students answering the same questions.

For three of the four subjects - research methods, U.S. history and law - the AI passed with a C or better grade. The top human scored better than the AI in each category, but in two categories (research methods, law), the AI beat one or more of the humans.

The subject it tanked was creative writing.

It would not tank creative writing anymore.

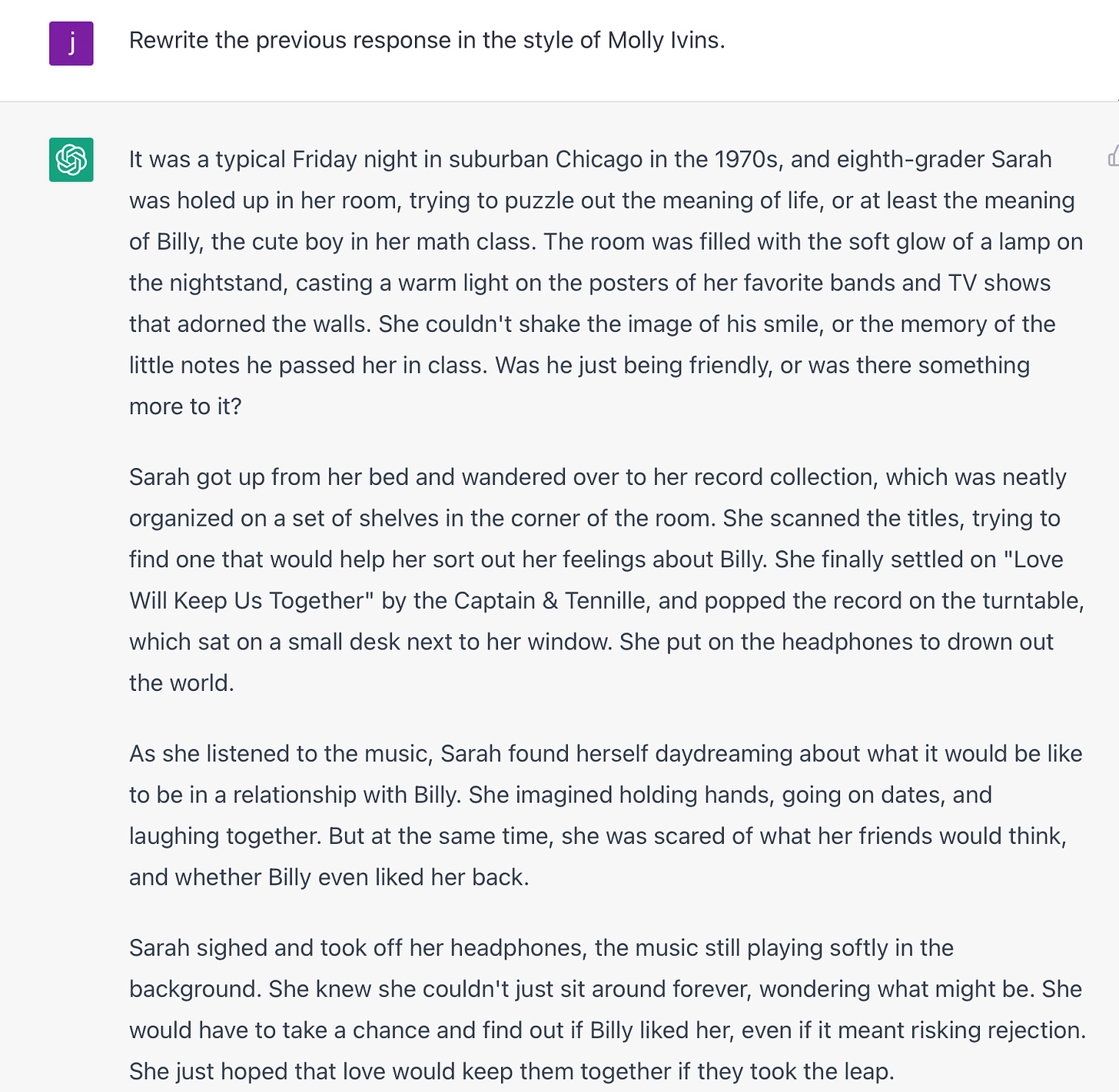

At the top next to the purple icon is my prompt. Below that is ChatGPT’s response. It took about 60 seconds for it to process and produce the text.

This is not good, exactly, but it also isn’t bad. It’s perfectly okay, not unlike the kind of thing that a student would produce in an introductory creative writing course. For a short story, that opening sentence is weird, but a clever student making a quick edit could excise it and improve the outcome immediately. In fact, a good overall editorial strategy would be to cut any line that’s explicitly in my prompt, so what remains is learned via inference. The weirdest part is perhaps the choice of song, as the upbeat spirit of the song and lyrics about a woman telling her partner not to be tempted by other girls doesn’t quite fit the scenario. It’s a good example of how the algorithm has no appreciation of meaning and context.

The passage also lacks a sense of place and atmosphere. The descriptions are sterile. I’m going to fix that with an additional prompt.

That’s actually starting to approach not bad. It’s not good, exactly, but in an introductory class, you don’t necessarily expect good. Still, it’s lacking something. It feels rather generic, voiceless. Let’s see if I can help it out a bit:

If you don’t know Molly Ivins, you should because she’s the best political commentary writer in the history of the genre, and she wrote in a very distinctive style.

This doesn’t actually sound like Molly Ivins writing about politics, but the prompt is enough to inject some spark of life into the prose. You can see a couple of immediate improvements over the previous version.

Compare these two sentences:

Eight grade student, Sarah sat on her bed in her room, staring at the ceiling as she thought about Billy, the cute boy in her class.

And

Eighth-grader Sara was holed up in her room, trying to puzzle out the meaning of life, or at least the meaning of Billy, the cute boy in her math class.

The latter is clearly better, more alive. “Holed up” and “puzzled out” are common phrasings, but clearly better than the generic language of the first example. And that line about puzzling out the “meaning of Billy” is downright good.

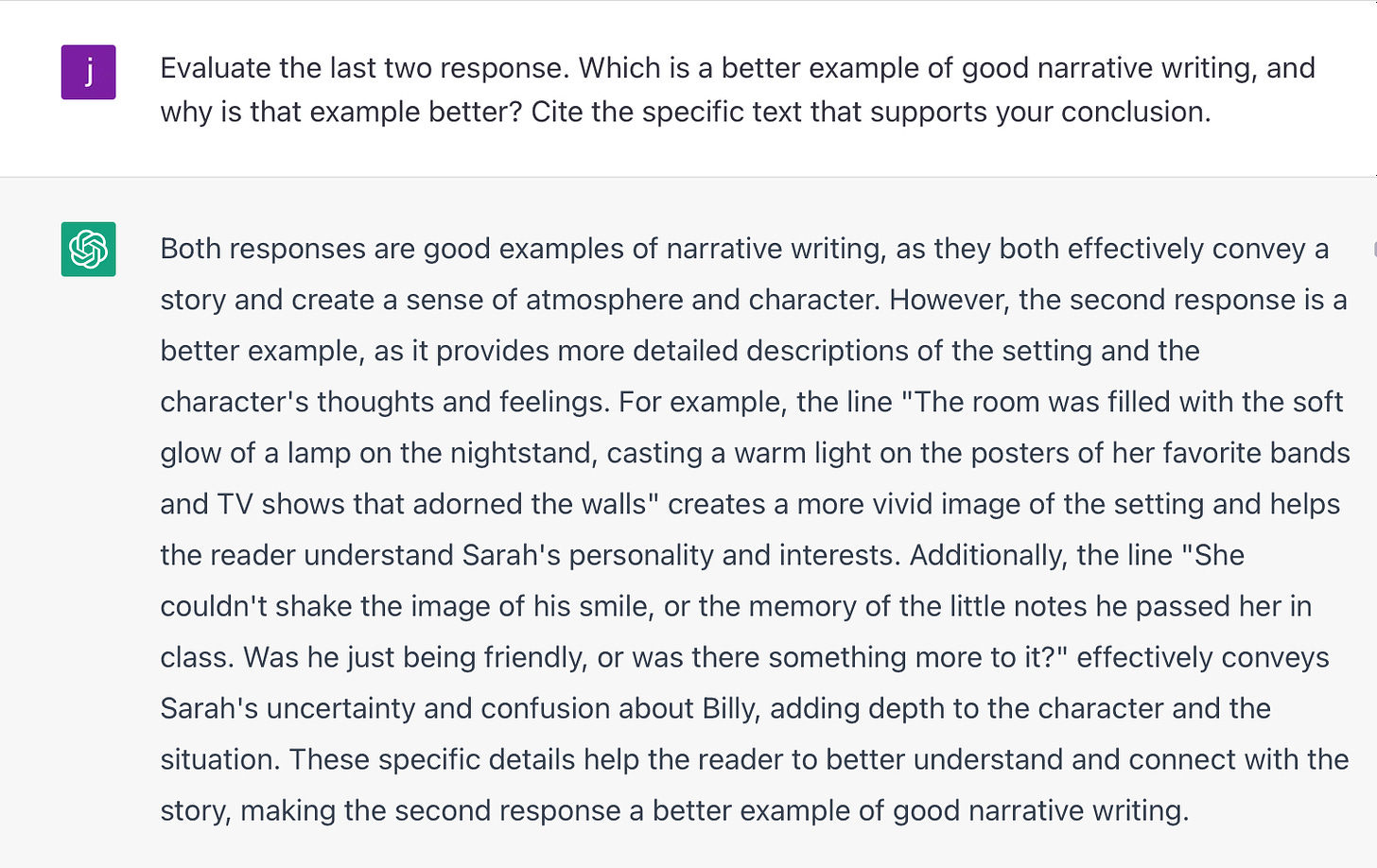

You know who agrees with me about which is the better narrative? ChatGPT.

If the AI can produce this, imagine what it can do with a canned prompt that you might commonly find in a literature-based high school English class, such as this one, from a sample AP Literature exam, “In many works of fiction, houses take on symbolic importance. Such houses may be literal houses or unconventional houses (e.g., hotels, hospitals, monasteries, or boats). Choose a work of fiction in which a literal or unconventional house serves as a significant symbol. Then, in a well-written essay, analyze how this house contributes to the interpretation of the work as a whole. Do not merely summarize the plot.”

I won’t bore you by pasting the answer, because it’s not worth your time to read it, but it would easily receive the maximum score a 5, particularly given the fact that the AP graders do not pay any attention to whether or not the content of the answer is accurate or true.

I cannot emphasize this enough: ChatGPT is not generating meaning. It is arranging word patterns. I could tell GPT to add in an anomaly for the 1970s - like the girl looking at Billy’s Instagram - and it would introduce it into the text without a comment about being anomalous. It is not entirely unlike the old saw about a million monkeys banging on a typewriter for along enough, that one of them would produce the works of Shakespeare through random chance, except this difference is, ChatGPT has been trained on a data set that eliminates all the gibberish.

Many are wailing that this technology spells “the end of high school English,” meaning those classes where you read some books and then write some pro forma essays that show you sort of read the books, or at least the Spark Notes, or at least took the time to go to Chegg or Course Hero and grab someone else’s essay, where you changed a few words to dodge the plagiarism detector, or that you hired someone to write the essay for you.

I sincerely hope that this is the end of the high school English courses that the lamentations are describing because these courses deserve to die, because we can do better than these courses if the actual objective of the courses is to help students learn to write.

But now that this technology is in the world, and will be widely available, we must think about what high school English should look like going forward. I’ve been thinking about these things for years, so I have a head start on others, but let me be clear ChatGPT has not created a problem that wasn’t already present.

Make the work worth doing.

One of the assumptions those who say this is the end of high school English make about students is that if students can find an end around doing the actual work of school, they will definitely take it.

What does it say about what we ask students to do in school that we assume they will do whatever they can to avoid it?

The final epiphany that cemented how wrong a turn we had made was the first time I stood in front of a class of first-year students on the second day1 of our writing course and I presented a hypothetical where I give them all A grades, but class would never meet, they would no no assignments, they would get no feedback or instruction. They would learn nothing. That first time I did it, about 60-65% of students said they'd take that deal.

Disturbing.

The last time I did it, six or seven years later, 85% said they'd take that deal.

Disastrous.

The students were not lazy or entitled. They were responding rationally to the incentives of the system. An A without learning anything was far more valuable than learning anything, and risking a grade lower than an A. School had nothing to do with learning, and writing courses especially were unlikely to be interesting or engaging.

Well, I set out to prove students wrong, that there was writing worth doing, and over the years developed the curriculum that is collected in The Writer’s Practice in order to try to prove that.

The experiences in the book are designed to be both intrinsically interesting, and to engender learning that is both visible to students and relevant to their lives. In my experience, students actually do want to learn stuff because students are people too. The problem is school has ceased to honor their humanity, instead substituting “student-ness.”

First step, et’s give students something worth doing.

Value the process, rather than the product.

It is a mistake to think we can out-prompt the AI. There are some things the AI is not good at yet - for example, it is an inferior lyricist to Steve Miller (not exactly known for the quality of his lyrics) when provided all the rhyming words from “The Joker.”

But for the typical school assignment, it reliably turns out passable results.

I’ve tested some of the core prompts that I use in The Writer’s Practice. In isolation, some are vulnerable to ChatGPT, while others would be very difficult for it to pull off convincingly at this time, but based on the progress I’ve seen, I have little confidence that we can stay ahead of its ability to bullshit.

But the reason why I’m confident my pedagogy is not vulnerable to ChatGPT is because I do not only grade the end product, but instead, value the process it takes to get there. I ask students to describe how and why they did certain things. I collect the work product that precedes the final document.

I talk to the students, one-on-one about themselves, about their work.

If we assume students want to learn - and I do - we should show our interest in their learning, rather than their performance.

Unfortunately, for the vast majority of my career, I did not have the time or resources necessary to fulfill the highest aims of my own pedagogy. The National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE) recommends each instructor teach three sections of a maximum of fifteen students each, for a total of 45 students. I never had fewer than 65 students in a semester, and some semesters had in excess of 150.

High school teachers are working under even greater burdens, and in more challenging circumstances. If the system will not support the teachers who must do the work, we may as well let ourselves be overwhelmed by the algorithm.

Raise the bar by getting rid of traditional grading.

The AI does not generate excellent work, particularly not without the kind of tweaking you see me doing above, tweaking which I can do because I possess a relatively sophisticated understanding of narrative craft and know what to tell the AI to do. A student doing an end run around school would likely accept the first thing the bot gives it, turn it in, and hope for the best. It’s similar to how plagiarists are easy to catch. They’re not diligent enough to cover up their perfidy.2

But part of the problem is that we - and very much including myself here - have been conditioned to reward surface-level competence (like fluent prose) with a grade slike a C+, B-, or B. We may have to get used to not rewarding pro forma work that goes through the motions with passing grades, or it may mean finding other elements of the experience to focus on in terms of grading.

This process of “ungrading” or alternative grading has been gaining significant momentum in recent years, and I think it is a promising way of figuring out what is meaningful to students and what kinds of approaches help them learn. For those who are curious about this movement, I recommend Susan Blum’s edited collection, Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (And What to Do Instead), but then again, I would because I wrote a chapter in it on Wile E. Coyote as the hero of ungraders.

Incorporate the AI into the work.

Having played around with this stuff for only a few days, my thoughts are early and provisional, but I could see potential in crafting assignments that encourage and empower students to utilize the AI in their work. At his Substack,

interviewed the author Chandler Klang Smith, about how she uses a similar technology, Sudowrite, to help produce her fiction. The AI could be used as a tool, or a toy in a way that opens up experiences of learning.I’m certain there’s people who are way ahead of me on how to do this well. I’ll be seeking them out and listening to what they have to say.

The reason the appearance of this tech is so shocking is because it forces us to confront what we value, rather than letting the status quo churn along unexamined. I couldn’t do that while I was teaching because the way students were struggling made me feel like I was doing a terrible job, and I wanted to figure out how to do better.

It’s possible that one of the things we (as in society collectively) will decide is that students don’t need to learn to write anymore, since we have technology that can do that for us.

I think this would be a shame because one of the things I value about writing, is the act of writing itself. It is an embodied process that connects me to my own humanity, by putting me in touch with my mind, the same way a vigorous hike through the woods can put me in touch with my body.

For me, writing is simultaneously expression and exploration.

In a piece like this, writing is the expression and exploration of an idea (or collection of ideas). It is only through the writing that I can fully understand what I think.

With fiction, for me, writing is the expression and exploration of for lack of a better word: life. Towards the end of my novel, The Funny Man, my narrator says, “Everyone’s got a story, and the best ones are those we tell ourselves.” That was a little Easter Egg I put in the text before I had any notion that it would one day be published as a reminder of how interesting it was to solve the puzzle of writing a novel. It is in the mouth of my narrator, but the sentiment is mine.

Writing is rewarding. Writing is empowering. Writing is even fun. As human, we are wired to communicate. We are also wired for “play.” Under the right circumstances, writing allows us to do both of these things at the same time.

It is not an impossible challenge to make this universe of experience accessible to students. We know much about what has to be done already.

It’s really a matter of whether or not we will decide to do it.

Exciting addendum on my response to ChatGPT

Since I first published this newsletter, I’ve been working on a course of instructors who assign writing that is designed to help them do their work in a world where ChatGPT exists. More info on the course and how to access it is available at this link right here.

Links

If you’re curious and want to read more reactions to ChatGPT, I recommend this piece from Ian Bogost on how we should see it a “a toy, not a tool.” The New York Times podcast “Hard Fork” asks, “Can ChatGPT make this podcast?” This piece by Stephen Johnson is a good one if you want to know more about how ChatGPT does what it does. Writing at Slate, Alex Kantrowitz says that Google has a chat bot that’s even better than ChatGPT, but releasing it disrupts their own search business model.

In my Chicago Tribune column this week, I share my favorite nonfiction and memoir of 2022, including Ancestor Trouble by

which I wrote about in an earlier newsletter when I asked "How do you know if a book is true?" Also included is Foreverland: On the Divine Tedium of Marriage by which I swear every married (or unmarried) person should read as a route to improving their own perspective on matrimony.Here’s a quick, music-themed quiz from the Times. I only got four out of five on this one, breaking my perfect streak on these quizzes.

Donna Barba Higuera, winner of this year’s Newberry Medal for children’s literature for The Last Cuentista, provides a list of her five favorite children’s books of 2022.

CrimeReads has released their list of best crime novels of 2022, while the Times has their take on the best true crime books of the year.

Brittle Paper introduces us to 100 notable African books from this year.

Recommendations

No requests in the queue, but let me remind everyone that all links to books from this newsletter go to Bookshop.org, and any affiliate income generated is donated to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is at $321.30 for the year. We’ve already topped last year’s total of $308.10, but what the heck, why not get to $400 before the year is out. As a reminder, I’m matching up to $500 of affiliate income.

Occasional more detailed plea for paid subscriptions

From the start, this newsletter has run on a patron, rather than consumer model, where I would keep the content free, while asking those who can afford and are inclined to support the project with paid subscriptions to do so.

It’s gone really well, as far as I’m concerned, but I was recently provided some data about how much more I would be earning if I put at least some of the content behind a paywall, and well…it is quite a bit more.

At the same time, putting posts behind a paywall would reduce the size of my readership, and my primary motive behind maintaining this space is to be read by a community of people interested in some of the same things I’m interested in, so I’m not going to put up a paywall, at least not for these weekly main posts.

But if you do like this newsletter and you can spare the subscription money to support it, I will be incredibly grateful, and the rest of the community thanks you as well.

Alrighty, time to go have a Sunday. You probably won’t be hearing from me next week because I’m traveling home to see family and I want to spend time with them, rather than tap tapping on the computer machine, but I have a new installment of “A Book I Wish More People Knew About” that will be coming your way.

JW

The Biblioracle

I’d always do this on the 2nd day, after I’d introduced them to the class and my teaching philosophy so I could get an honest answer.

Because of how I grade the writing process than merely the final artifact, I didn’t have a plagiarism case for the last decade or so of my full-time teaching career, but the appearance of “perfidy” in a student essay was a red flag for something that had been copied, as the semi-clever plagiarist will copy another text, and then using the thesaurus function on their word processor, substitute some synonyms for a handful of words, in order to throw of any search attempts. In order to catch these students back in the day, I would write out all the words from an essay that I suspected had been thesaurasized and ask the student to define them on the spot. Sort of mean, but effective.

Let me say something about repetition and patterns. I spent 27 years as a coach and judge of HS Forensics. I've spent countless hours listening to students use 3 point analysis to explain why the US should continue to fund NASA (for example) and I've sat through countless debates on resolutions like, "Resolved: Civil Disobedience is a just response to oppressive government."

By and large, regardless of the topic or the resolution, students followed certain formats. In Debate (Lincoln Douglas debate) it was the Toulmin rhetorical method (Claims, Evidence, Warrants, Impacts) and in Extemporaneous, it was generally 3 point analysis organized around time, location, or hierarchy.

Over time, as a coach, my students became far more fluent and advanced in their rhetorical choices, and their choices were more agile, creative, and nimble.

But they could not have gotten there without first understanding these forms.

And yes, debate is a game with rather predictable patterns at the novice level. But at some point, with enough experience and real-world feedback, they make a huge cognitive leap.

Surely I'm not suggesting that all students should engage in the rigorous and often ridiculous event of HS Forensics, where some of the very best speeches I've ever seen are those that lampoon just how predictable their speeches are.

But I am suggesting that kids need lots and lots of practice and that understanding the importance of form as a scaffold is important...so long as we also understand we need to help them move away from this.

I've spent thousands of dollars and endless hours freewriting and revising work through attendance at Bard College's Institute for Writing and Thinking. I know how I write, and that knowledge is a debt I owe to Peter Elbow, who never taught the way most HS English teacher teach:

"The Teacherless Writing Class

According to Elbow, improving your writing has nothing to do with learning discrete skills or getting advice about what changes you need to make. This stuff doesn’t help. What helps is understanding how other people experience your work. Not just one person, but a few. You need to keep getting it from the same people so they get progressively better at transmitting their experiences while you get better at receiving them."

If what ChatGPT does is, as you and many here and elsewhere are saying, is force out those who profess forms and efficiencies over voice and engaging prose, then count me in. I'll put on my VR headset and lead the way to something more human, something unpredictable, something closer to our own truths in words.

I confess a fondness for the five paragraph theme, but mostly only as a means of writing parodies of five paragraph essays. I don’t really want to teach again (through I did teach an online writing class a year ago), but I do think I’d do a much better job at 47 than I did at 24, in part because I’ve realized that writing is genuinely difficult for a lot of people—and that coming up with forms of writing that make sense as “writing one might actually be called upon to do in one’s actual life” is a better mode of approaching the whole business.

(Some day perhaps someone will decide I am qualified to teach seminars on How to Write a Work Email in addition to my dream job of of teaching people How to Run a Meeting.)