C. Michael Curtis passed away this past week.

If that name means something to you, there’s a good likelihood that you’re a writer, perhaps age 45 or older. If you don’t know that name, but are a reader of literary fiction, C. Michael Curtis almost certainly had an influence on some of what and who you have read in your lifetime.

Curtis was an editor at The Atlantic magazine from 1963 to 2005, fiction editor from 1982 until the end of his tenure, an end which was essentially also the end of the The Atlantic publishing fiction altogether. He helped introduce readers to the work of Louise Erdrich, Joyce Carol Oates, Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie, Bobbie Ann Mason and innumerable others.

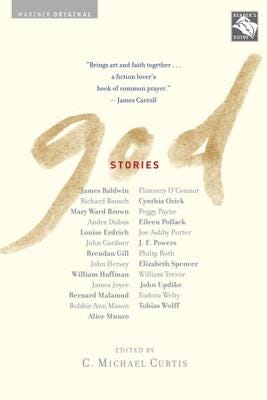

Curtis did not have quite the profile of famous New Yorker-associated editors like Robert Gottlieb, Daniel Menaker, or Roger Angell, but he is of that ilk. A somewhat late arrival to Christian belief, his two edited anthologies, God: Stories and Faith: Stories collect writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, John Updike, Alice Munro, Flannery O’Connor, Philip Roth, James Baldwin, and others exploring the experience of belief. I once had a very curious, very devout evangelical Christian student at Clemson who saw God: Stories on my office shelf and asked to borrow it. When they returned it at the end of the semester, I asked what they thought, and they said it wasn’t what they expected. I asked if that was a good thing, and the student replied, “I’m not sure.”

C. Michael Curtis was also the source of a rejection that had the effect of encouraging me to keep writing during a period when I was very uncertain about whether or not such at thing was still a good idea.

At the time, I was operating under the belief that if I just could publish a short story in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, or The Atlantic, I might be able to have a career as a writer. These were the gates, and if I could get past them, a life I wanted to desperately that wouldn’t even admit it, would open to me.

(This was a mistaken belief, as that era had already passed, but it was a legacy that had been handed down to by the generations before me.)

This was not too long after I’d finished graduate school in 1997, and up to that time, not only were the gates to a future as a writer closed, but I when I would go knocking, I couldn’t even tell if anyone could hear me.

Before the Internet and electronic submissions, everything was printed and mailed, and as part of the package you included a self-addressed, stamped envelope in which the response to your submission would be sent. Whenever one of those envelopes appeared in my mailbox, I’d have a brief rush excitement before peeling it open and seeing the inevitable rejection. The rejection itself wouldn’t even be printed on a full-sized sheet of paper. Most often it was a thin strip, many times xeroxed, sliced crookedly from a larger sheet. Sometimes it would be stapled to the first page of your story, always a form response, perhaps some initials indicating that it had been read or at least glanced at by a human.

At that time of living out of my parents’ basement as I tried to figure out what might be next, there was one exception when it came to the form rejections. It was from C. Michael Curtis, a 5x8 sheet of paper with The Atlantic letterhead. I kept it for years, though now I don’t even recall what story it was for, or the specifics of what he said, other than two words, “interesting,” and “unusual.”

Don’t get me wrong, it was still a rejection, but someone had read the story! Not just someone, but C. Michael Curtis. And it was interesting! And also…unusual!

Years later, after I’d started editing the McSweeney’s website, and not long after Curtis had left The Atlantic, we appeared on a panel together at a book festival sponsored by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and I got to tell him how meaningful I’d found that rejection. I got the sense he’d heard similar sentiments many times before, but honestly didn’t make much of them. He’d simply been doing his job, which was to read and respond to the fiction people sent him. He thought such behavior ordinary, but I can tell you from the perspective of someone sending his work into slush piles across the country at the time, it was extraordinary.

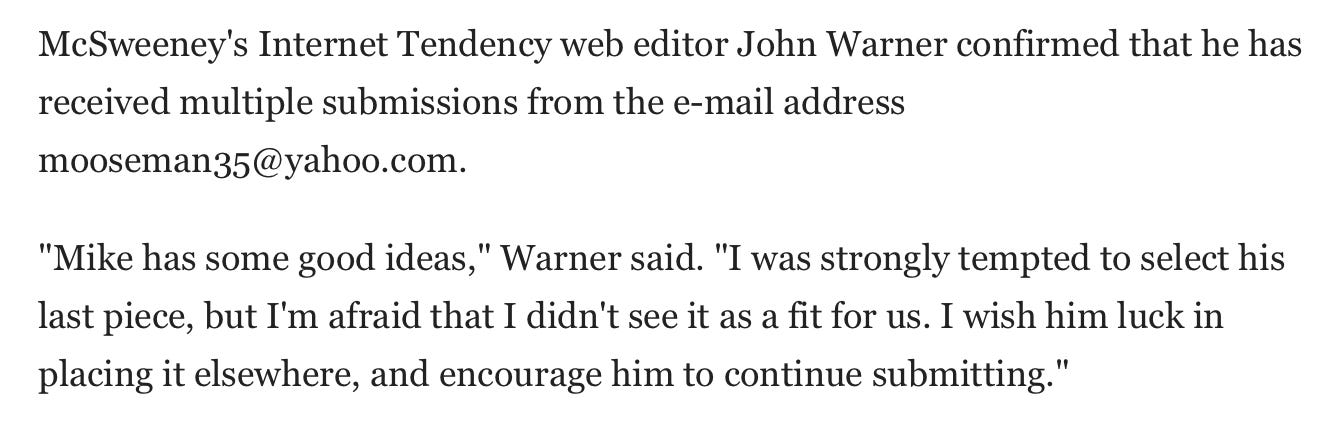

The honesty and courtesy Curtis extended to people submitting to The Atlantic is something I consciously tried to model when I was rejecting dozens (and then hundreds) of pieces a week at McSweeney’s. My pattern and practice became so predictable, it was once lampooned in an article in The Onion:

Whoever wrote the article nailed my style:

I’d never been so proud to have been made fun of, and I can honestly say that how, and how quickly I responded to the writers who submitted to the McSweeney’s website was influenced by how C. Michael Curtis had once responded to me. I remembered how a small thing to him had made a big difference to me, and tried my best to do my editorial screening in the same spirit.

A gracious man, dedicated to his work, serving others in the process. What more could one ask for in a life?

My Chicago Tribune column this week is about the demise of Bookforum, the magazine of literary criticism in specific, and the general impossibility of operating a literary publication in general in a world where you need to have a “business model” that touts profitability, even if that business model is pure fantasy, as is the case with a company like Uber, which, along with its ride-hailing brethren, has a business model that is more expensive to operate than good, old-fashioned telephone dispatch companies.

A single quarter of losses for Uber would fund the entire literary magazine ecosystem for a lifetime and then some. Uber has lost more than $30 billion during its existence. It is hard to truly envision the scale of these kinds of losses and what that money means. As a way of comparison, consider that the proposed sale price of Simon & Schuster, one of the five biggest publishing companies in the world, a company that is actually profitable was $2.2 billion.

C. Michael Curtis was at The Atlantic up to the end of the period when literature was subsidized, and not necessarily something to sacrifice on the altar of profit. In 2005, The Atlantic’s new owner decided that the cost of a full-time fiction editor was one of the sources of the publication’s red ink, and sun-setted Curtis’ job, taking out yet another of the places that once had the power to make a writer’s career.

But even at 71-years-old, Curtis was not done, becoming intimately involved in the Hub City Writer’s Project and Hub City Press in his adopted hometown of Spartanburg, South Carolina. I highly recommend this 2020 article by Hub City editor Betsy Teter on the passion with which Curtis tackled this phase of his work.

Curtis is really, pretty much the last of his kind. The days when a young person without specific direction can latch on to an editorial job at a legacy publication and stay there for 40 years, quietly shaping the culture is long gone.

There’s no business model for that anymore.

Links

I’ve been negligent in not alerting folks to the full announcement of the Tournament of Books shortlist, brackets, and judges. Get your reading done in time for its launch in March.

I’ve also been negligent in keeping up with one of my 2023 reading resolutions, to read more crime fiction, but that’s because I’ve been busy reading for the Tournament of Books. I’ve got this list of anticipated 2023 titles from CrimeReads bookmarked for future reference.

I honestly can’t keep track of which anticipated books lists I’ve already shared, so maybe this one is a repeat, but here’s one from LitHub. I actually saw some publishing industry folks on Twitter talking about how many the anticipated lists deal had ceased to be significantly beneficial to a book’s sales because of proliferation and saturation of these kinds of lists, and I think they might be on to something.

At Slate, Laura Miller writes about the rapidly improving quality of AI audiobook narrators and what this means for the industry. On the one hand, it may allow many more books whose sales don’t justify the cost of audio production to become audio books. On the other hand, it’s an obvious threat to the highly skilled humans who currently narrate audiobooks.

Colleen Hoover may be an author with a strong brand and loyal following, but that passion recently created some backlash when those fans pushed back against the idea of an adult coloring book tied to her domestic violence novel, It Ends With Us. The fans said, “WTF,” and Hoover said, “my bad.”

Speaking of business models…

Before I get to the recommendations, I promised last week to update folks on how things are going in terms of paid subscriptions. As I wrote in a previous post discussing the difference between “consumers and patrons,” this newsletter has no business model other than asking people who enjoy this content and can afford to support it to contribute to its continuation.

I was primed by other experienced Substackers to expect a dip in annualized revenue at the anniversary of turning on paid subscriptions, which happened this past week, and while it could’ve been worse, those warning weren’t wrong, as annualized revenue fell by about 10%. While we’re still at sustainable levels, this setback does mean that I have to (hopefully only temporarily) delay my plan to hire a part-time assistant who could enhance to offerings.

Every metric Substack provides shows that I would earn approximately twice as much revenue if I put up a paywall on these posts, but it would also cut my audience by more than half, which strikes me as a bad trade off. Why would I write except to be read? I am not willing to make that sacrifice on the altar of the business model.

That said, fewer than 10% of all subscribers are paid subscribers, and if that number could get up to 10%, I could not only hire a part-time assistant, but also pay for content from outside contributors at least twice a month.

End of heartfelt plea…

Recommendations

All links to books from this site go to Bookshop.org, and affiliate income will be donated to Open Books of Chicago, and another book or reading-related charity to be named later. I’ll also match the affiliate income with a donation of my own up to 5% of annualized revenue or $500, whichever is larger.

1. The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

2. The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

3. Macbeth by William Shakespeare

4. Foundation and Empire by Isaac Asimov

5. Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens

Darryl W. - Midway, UT

Okay, no degree of difficulty here, just a list of widely acknowledged classics. In that spirit, I’m going to recommend a book that was largely forgotten, but was recently republished, and should absolutely be considered a great American classic, A Different Drummer by William Melvin Kelly.

It’s cold where I am today, and I’ve already got the bulk of it earmarked for reading while nice and warm underneath a blanked, in front of a fire.

Until next time…

John

The Biblioracle

(Finally circling back to this.)

I never submitted anything to C. Michael Curtis, but I've read a rejection he wrote several times--it's to an article* my godfather wrote about the demise of Parsons College and is among my father's papers, as my dad was deeply involved in the story of said demise. I've read the article, too, and it's not quite good. Curtis's response is a page or two long and precisely nails just what isn't working in the piece but does so in the most courteous and useful way possible. It's stayed with me.

*Why Curtis was handling an article and not a piece of fiction is probably related to who my godfather was at the time and that he was primarily a fiction writer, or at least that's my guess.

As a young writer today, what would you guess is the best route: literary journals? Publishing on Substack and building an audience? Something else?