Against Optimization

I want to live, dammit!

Note: This post is too long for most email clients to display in full. Please click through for the full post online.

As anyone who reads me will recognize, I am not a language pedant, but there is one usage over which I am a bit of a stickler: “begging the question.”

The incorrect usage conflates “begging the question” (or “begs the question”) with essentially, “raises the question” as in, “Donald Trump threatening to arrest and jail his opponents begs the question as to whether or not Democrats can come up with a strategy that speaks to the needs of regular Americans.”

The way I remember begging the question is to remind myself that it’s referring to a statement where a question has gone begging, unasked, with an answer assumed. If you are begging the question you’re skipping a previous step in an argument, usually to brush past a weak point in that argument.

I encountered a world-class example of begging the question in a recent interview on the Hard Fork podcast co-hosted by tech columnists Kevin Roose of the New York Times and Casey Newton of Platformer.

Roose and Newton were talking to two of the founders of Mechanize, a Silicon Valley startup that openly declares a stated intention is to automate everyone’s job. In a piece profiling the company Roose remarks that he finds this frankness refreshing. Rather than paying lip service to “enhancing productivity” or creating “AI co-pilots,” these dorks just come right out and say, “all your jobs are belong to us.”

I’m not even going to bother with the holes in their approach to automation or their belief that the vast majority of jobs could be automated or the absurdity of the timeline in which they say this will happen (within the lifespans of most people alive today). Instead, I want to zero in on a question (or two) gone begging that I think is rather revealing about where we find ourselves today.

In the Hard Fork interview, the Mechanize founders are asked if what they’re proposing is “ethical.” After all, they are threatening to displace people with jobs, jobs they depend on for food and shelter and subscriptions to Netflix. Mechanize co-founder Matthew Barnett admits that when it comes to automation there will always be a tradeoff of costs and benefits, but in this case, the many fold increase in production will have such outsized benefits. any costs will be worth it.

This is how Barnett frames these benefits:

Here is the question that Barnett has left begging: Is a high quality of life predicated on mass consumption?

I mean, maybe we can kick this around for a bit, but I’m going to just go ahead and say that the answer is no.

Barnett goes on to suggest that once people no longer have to work because of this massive abundance - how that abundance is going to be shared TBD, BTW - that we will be compelled to do other things with our time. Here’s what he’s come up with:

His “default” prediction once jobs, including white collar professional jobs like coding, lawyering, doctoring, teaching, et al…is that people will go to college.

I have a different prediction as illustrated in an image from a popular film depicting a world where labor has been automated thanks to the dedication of (very cute) robots.

I spend a fair bit of my time lately wondering if I’m the crazy one when I hear tech industry tales of unlimited abundance and think that it all sounds kind of shitty. Like Roose, however, I am grateful that the Mechanize-ers are so forthright about their intentions. Most tech companies tout the benefits of increased efficiency or optimization to human activity, but these guys are saying “Nah, don’t need you at all.”

This was the week a couple of things locked into place for me, helping me better understand where these people are coming from, why I am so out of step with their world views, and why I believe they must be resisted.

In theory, optimization is fine, and there’s many ways we could all benefit from efficiency, but there is an ideology at the center of this - one well illustrated by the mindset of Matthew Barnett that seeks to remove all friction.

This is not the promise of optimization, but of liberation.

But liberation from what, exactly?

Honestly, it seems like they intend to liberate us from the experience of living and replacing it with lives of bottomless consumption.

—

I shouldn’t let the question go begging.

What then, is a good life? For the co-founders of Mechanize, maybe they’d say something like “tackling hard problems that could potentially be solved with technology.” They do not seem to know or care that someone else’s life is viewed, by them, as a problem.

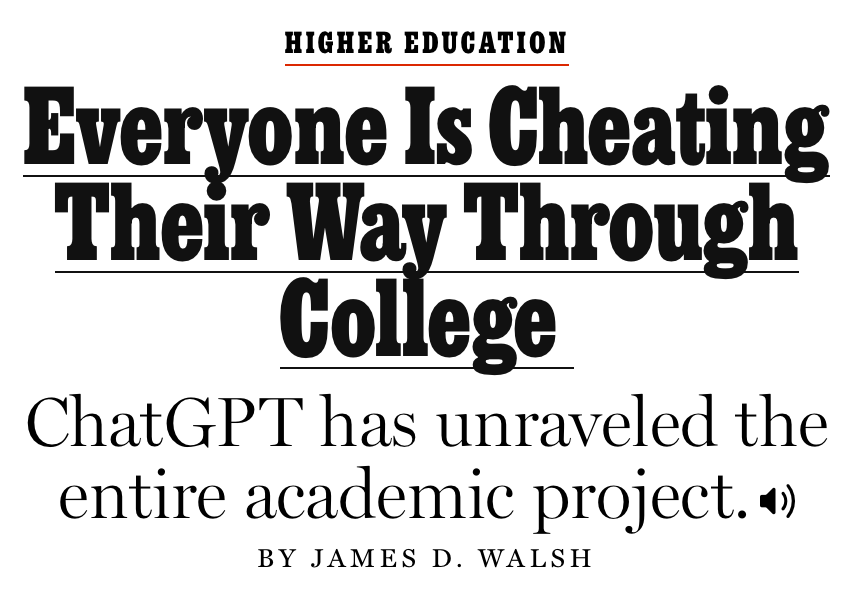

It is not surprising that they see liberation in mass consumption, and that a transactional exchange is the clearest and best expression of desire. A transactional mindset appears to be at the center of everything these days, most definitely and most distressingly our system of schooling, the place that Matthew Barnett thinks people are going to run to once they no longer have jobs.

Addressing the Transactional Model of School

There was one thing top-of-mind for the people in my world last week.

Apparently, the theory is that we’re going to mechanize all knowledge work to free us up to work on our minds?

Meanwhile, there are signs in many places that lots of knowledge workers are becoming less interested in the work of building knowledge, at least not without the “help” of AI.

Also at the New York Times this week, Bill Wasik, the editorial director of the New York Times Magazine profiled the work of popular historian Steven Johnson who has been working with Google on developing their NotebookLM application that uses large language models to distill sources fed into it. Wasik watches as Johnson delivers various bits into the application - here I am picturing a SeaWorld trainer dropping fish into the open maw of an orca - looking for connections that might spark an approach to a book Johnson considering on the California Gold Rush.

None of these activities involve Johnson, you know, reading. For sure, he’s done lots of reading in his life and has developed an ability to suss out a potentially interesting thread from what the model brings him, but it’s also important to see Johnson as a popular historian a kind of Malcolm Gladwell of historical events or concepts who relies on the spade work of actual historians to deliver the goods which allow him to spin a palatable, readable, accessible, popular narrative that will draw a much larger audience than the much more detailed, narrower histories he’s feeding into NotebookLM.

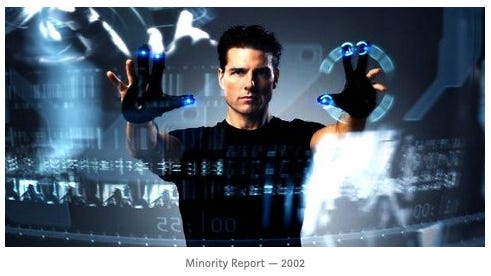

Johnson’s skill is an ability for evaluation of the data, a skill that he is augmenting by having a tool that can bring much more to his attention. Now I’m picturing that scene in Minority Report where Tom Cruise is sorting through the feeds of the pre-cogs who are delivering premonitions of future crimes.

Cruise’s (apparently unique) talent in the film is to put the threads together in a way that reveals the crime that’s about to happen in time for the government storm troopers to drop in and interrupt it before it can occur. Of course in the movie (spoiler alert), some of the data has been tampered with, sending a false signal, obscuring the truth.

If a student were doing what Johnson is for a school assignment we would say they are cheating, but because Johnson is a respected and best selling author, he is simply working smarter or more efficiently.

But the truth is that Johnson has always been a remora on the backs of genuine historians, gifted at spinning an entertaining yarn, but largely useless in the deeper act of discovery and interpretation. Johnson’s books, as clever and readable as they are, are pablum as compared to the original sources he relies on to make his books.

His career rests on the fact that it is much easier to ingest pablum and that we’ve somehow been convinced that stuff that isn’t pablum, the stuff that requires effort - be that writing or reading - is defective and must be fixed.

Knowledge work is actually late to the game on this front. Consider Soylent, which bills itself as “the world’s most perfect food.”

Apparently the most perfect food has eliminated those annoying aspects of eating like chewing, or tasting. This is optimized food. Johnson is pursuing a kind of optimized nonfiction book production.

At one point Wasik seems to fall under the spell of what NotebookLM seems to offer:

Like most people who work with words for a living, I’ve watched the rise of large-language models with a combination of fascination and horror, and it makes my skin crawl to imagine one of them writing on my behalf. But there is, I confess, something seductive about the idea of letting A.I. read for me — considering how cruelly the internet-era explosion of digitized text now mocks nonfiction writers with access to more voluminous sources on any given subject than we can possibly process.

Wasik wants to be liberated from the fear that you’ve missed something by outsourcing it to the large language model. This presupposes that the key to a positive outcome is consuming as much as possible, and if you can’t consume itself, why not have the LLM chew your (intellectual) food for you?

I don’t know how much more cynical this can all get. A startup called Cluely just secured $15 million in funding for an app that promises to help you cheat at “everything.” Nothing matters.

I also don’t know that I have a ton of answers for what it is to live a good life, and those answer likely vary considerably from person to person. I don’t want to optimize my nutrition. I want to eat a delicious meal. I don’t want to outsource my reading. I want to connect to a book.

It is past 1pm on a beautiful Saturday. I could be out doing anything right now, but here I am working on my newsletter. I don’t pretend that any of my outputs truly matter, but I’ve been deeply occupied by this activity for several hours now.

This is living, isn’t it?

Links

At the Chicago Tribune I extolled the virtues of great summer reads by three authors whose virtues I’ve extolled previously Rob Hart (The Medusa Protocol), Megan Abbott (El Dorado Drive), and

(Murder Takes a Vacation).At Inside Higher Ed I give my advice for dealing with the existence of large language models in the classroom, “do less that matters more.”

The philosophy professor and author Helen De Cruz passed away Friday, June 20th. I only knew her through her writing, including her newsletter here Wondering Freely and her book, Wonderstruck: How Wonder and Awe Shape the Way We Think. By coincidence as I was compiling the sources I planned on using for this installment someone surfaced her last post from her newsletter titled, “Can’t take it with you.”

De Cruz wrote it three weeks ago while in hospice, knowing her death was imminent and reflecting on what makes life worth living. She argues, convincingly, that life should be spend in the pursuit of our passions.

Via my friends

“Acts of Rebellion for the Middle Aged” by Liz Alterman.Recommendations

1. Butter by Asako Yuzuki

2. Knife by Salman Rushdie

3. Mothers and Sons by Adam Haslett

4. They Called Us Exceptional by Prachi Gupta

5. Planes Flying over a Monster by Daniel Saldaña París

Andrea C. - New York, NY

I get kick out of the titles of those first two books one after another. Actually, if you read all the titles down the margin you get yourself a strange little poem. As for what Andrea should read next, I’m recommending Tom Rachman’s The Italian Teacher.

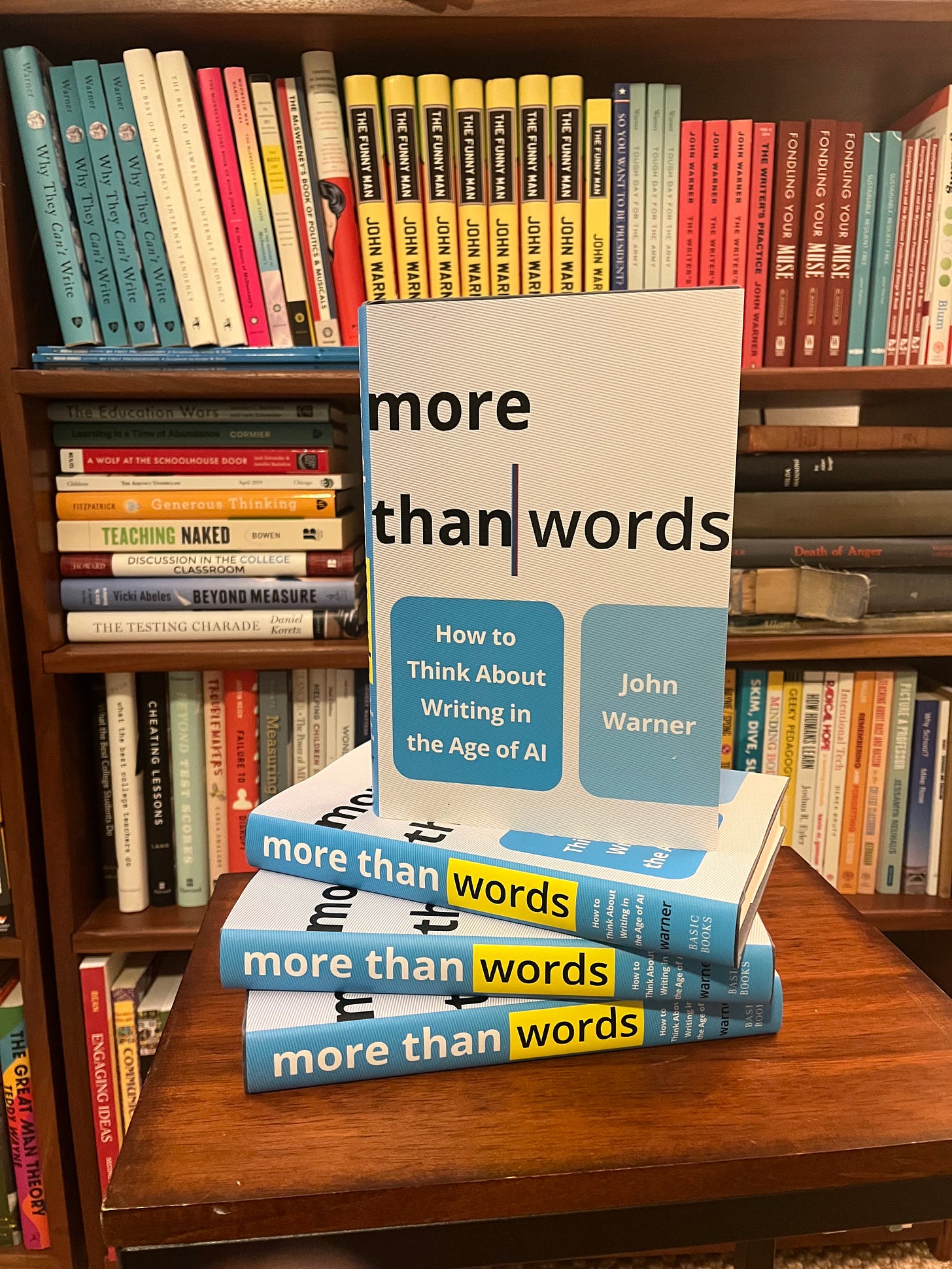

The central claim of More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI is that writing as an experience and the process of writing is where we experiencing the most meaningful part of the act. For sure, I get a kick out of knowing that some people will read these words and respond with words of their own in kind, but the true pleasure is truly in the doing. I just can’t believe how many people - including some who identify as writers - are willing, even eager to let those things go.

Go forth, have experiences! I’ve got a Q&A with a favorite author that should be ready for Tuesday, so look for that.

JW

The Biblioracle

Mary Chapin Carpenter has a gorgeous new song on this topic called “Girl and Her Dog.” One line is “And the older I get the more I'm sure

That more by itself never was a cure.”

I consider myself both a writer and a reasonably intelligent person, and yet I have never been able to get "beg the question" straight. I therefore avoid using it entirely, as I do know it has a specific and useful meaning that I don't wish to further degrade.

(Thinking about words and images and following thematic designs, I suppose, my idea of a good life.)