Addressing the Transactional Model of School

We need to attack thoughtless ChatGPT use from the demand side.

There was one thing top-of-mind for the people in my world last week.

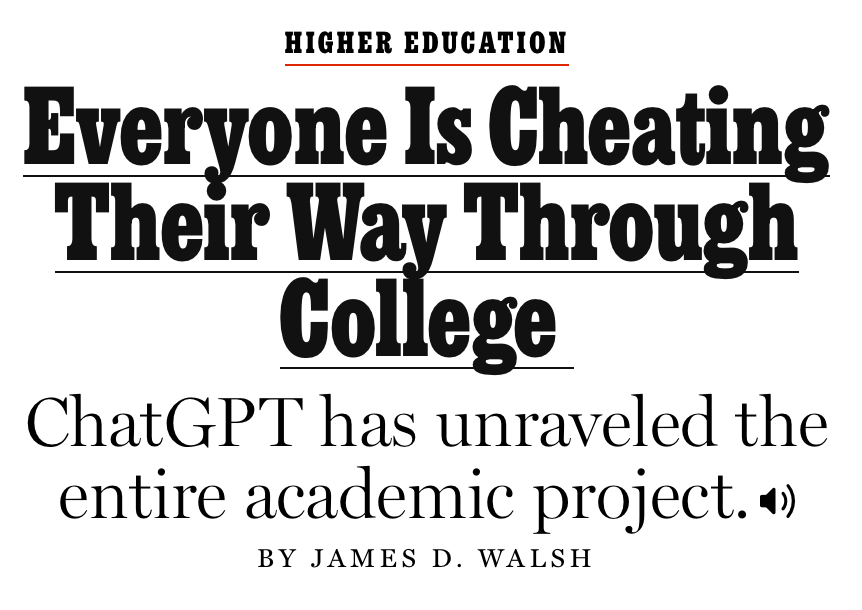

It is a grim tale of students relentlessly and aggressively optimizing generative AI tools to do their schoolwork from them. The tale of Wendy is central to Walsh’s story.

There have been a variety of responses to the story, which has broken containment beyond the worlds of teaching and learning that I circulate within to infuse the broader zeitgeist.

This is New York Times tech columnist Kevin Roose on X:

Roose is correct that we should all be rethinking what writing in school contexts means in a world where tools of syntax generation exist. It seems like I’ve heard about a book covering just this subject.

But I am here to testify as someone with twenty years of experience teaching college writing, as the author of several books concerning the teaching of writing who now flies and Zooms around the country to talk about this problem and work with people to ameliorate the negative effects of this technology on student learning, it is not this simple.

Yes, course and assignment design matters and there’s much we can do on this front. I would also argue that the way we assess student outputs in response to the assignment is even more important than the design of the assignment itself.

But there is no doubt in my mind that to truly address these issues, we must attack the unproductive use of generative AI - essentially when students choose to outsource their thinking to the thing that can’t think - from the demand side.

Here is the question on my mind after reading the story and seeing young Wendy’s part: How did Wendy make it to college internalizing that her ideas do not matter?

Before moving on, we should add a little context . As it happens, I spoke to James Walsh for the story, and while I am not quoted, I can perhaps detect some influence of what I had to say, namely that students are behaving according to the incentives of the system within which they exist. When you are judged solely on the product, when the stakes of good grades seem existentially high, when there is doubt or uncertainty about your ability to perform to the standard you believe is expected of you, reaching for this aid is understandable. If you do it often enough and the system seems to keep rewarding you for it, why would it become anything other than normal?

But the presentation of the magnitude and intensity of the problem is unfortunately exaggerated in a way that I fear has the potential to induce a moral panic response which will not lead to a productive discussion about what to do. I hope everyone knows that not “everyone” is cheating their way through college.

Just yesterday I had the chance to have a very enlightening conversation with a handful of students at the University of Chicago as part of a truly amazing symposium put on by their Chicago Center for Teaching and Learning. Maybe you think me a fool for taking students at their word, but several of these students said they don’t use these tools at all. No interest. Others described using them in ways that are genuinely mindful and “agentic.” Of course these students also reported that they’d seen behavior like Wendy’s among friends and classmates.

I hope everyone also knows that reducing the issue to whether or not students are “cheating” is not particularly helpful either. While generative AI use has implications for academic integrity, its implications reach far beyond that relatively narrow frame.

The bigger issue is what happens if we have successive years of graduates who have not had a genuinely meaningful educational experience. Are we on the way to creating a nation of clueless dumbshits?

Have we not already achieved this, though? Is Big Balls, the notorious member of Elon’s Doge Army not already a fully realized dumbshit?

I’m more worried about the Wendys of the world, the students who have internalized a transactional model of education that has turned students into customers, where the exploration and development of the self is secondary to doing whatever the transaction demands to continue to progress through the system. Wendy exists in a system predicated on what I call “indefinite future reward” where there is no reason to do something in the moment. All of the payoff is at some future point. Get good grades in high school to get into college. Do well in college so you can get a good job. Get a good job - meaning high paying - so you can insulate yourself from the uncertainty of the world as much as possible.

If you’re really lucky and become a billionaire like Mark Zuckerberg, even as our democracy slides toward autocracy, India and Pakistan get perilously close to lobbing nukes at each other, and the planet heats up, you can retreat to your underground Hawaiian lair where you won’t be lonely because you have your AI friends.

I just described a dystopia that also resembles reality. Make of that what you will.

It is frustrating to have the Kevin Rooses of the world drop in with their half-informed opinion when you (I) have spent the last 20 years working on the problem of helping students learn to write not just as a skill for future employment, but a way of living as an engaged person in the world.

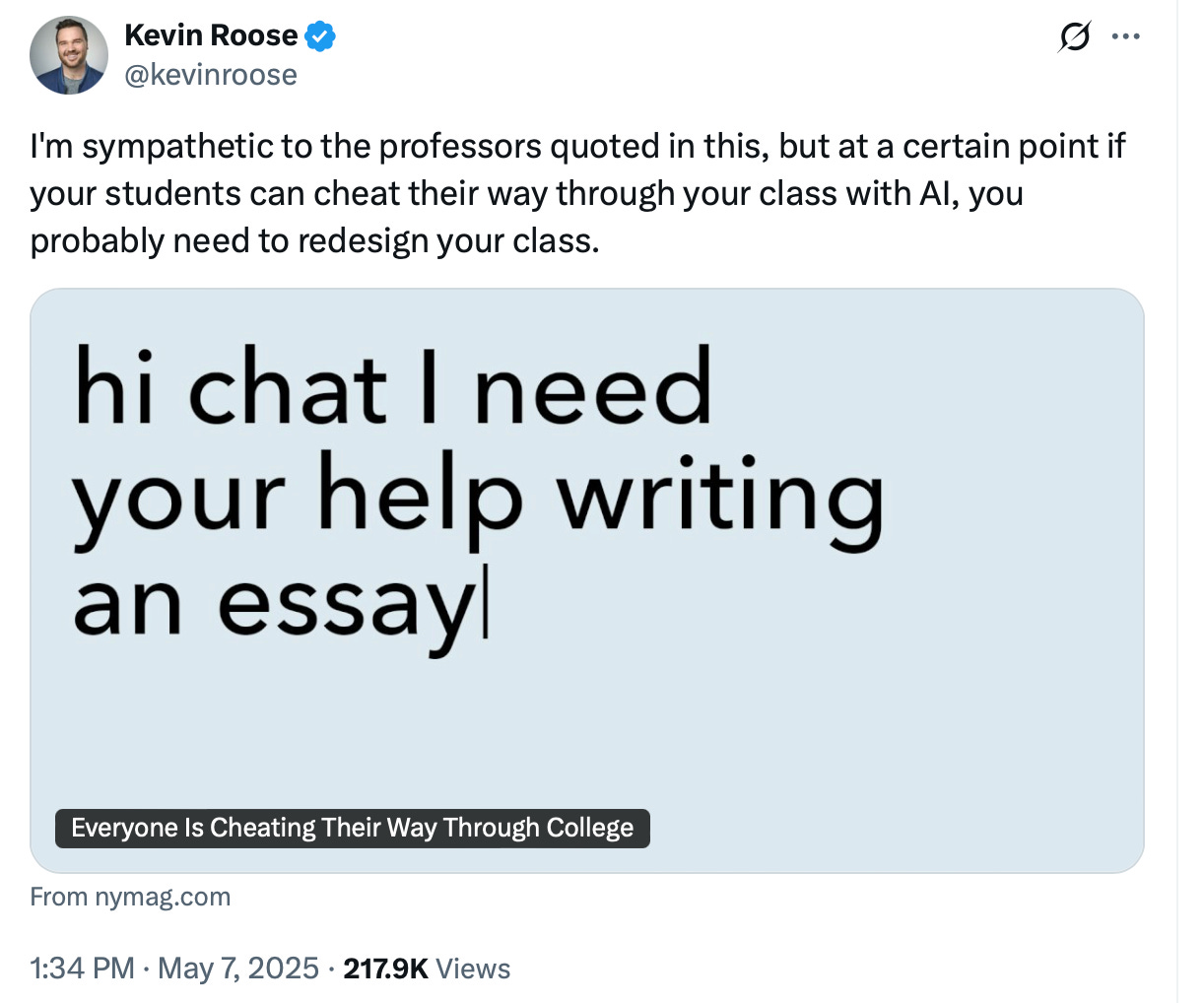

If folks want to know how Wendy made it to college believing her ideas don’t matter, I have a book recommendation, mine: Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities.

The first half of the book unpacks the myriad forces that resulted in students not writing in school, but instead creating writing simulations for the purpose of a grade. It is a story that goes back to the 1980s and describes the atmosphere in which the LLM homework machine has detonated causing all of this terrible fallout.

If you want a curricular blueprint for writing experiences that stand a chance of engaging students in ways that make them less likely to outsource their thinking to a non-thinking machine, I got that covered too: The Writer’s Practice.

If you want a book that articulates why writing matters and why we should be working urgently to change the system that has students like Wendy believing what she thinks doesn’t matter, may I suggest More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI.

Look, I’m not saying I have the solution to the problem, or that solving it will be easy, but there are a lot of people who have a good handle on the nature of the problem, who have been thinking about it for quite some time. Most of those people are teachers, but these people are largely shut out of the conversation.

I’m tired in two ways right now. For one, I’m weary of these issues that can absolutely be addressed productively being turned into a moral panic that makes it hard to do so.

But in this moment, I’m also tired in that satisfying way of having done something big that feels good and which means you deserve rest. My trip to Chicago for symposiums at Northwestern and U. Chicago were amazingly generative and encouraging. At Northwestern I heard from a dozen or more other people also thinking about these issues and came away with a fresh appreciation for the different ways we can attack the problem.

At U. Chicago I interacted with a few dozen faculty who showed up towards the end of the quarter in the midst of their busiest time of the year to listen to me speak and share their own perspectives, questions, and concerns.

Great progress is being made. I want to be part of that progress. I hope that anyone who thinks I might be able to help them takes the opportunity to contact me.

This is a fight worth winning.

But for the next day or so, I’m going to rest. I hope you all do the same should it be to your benefit.

Additional excellent reading

One of the things we should be doing is having better conversations. This is the core intention behind how I write my books, to generate conversation. In the last 72 hours I’ve read a number of perspectives on the issue that I’ve benefitted from and so I’m sharing them with you.

says “The Worst Thing About ChatGPT in Schools Is That it Kills Trust,” to which I say, “absolutely,” and that it goes both ways, teachers’ trust in students that they are doing their work, and students’ trust in teachers that their ideas matter. shares “What Makes Me Mad about AI in Education.” I think her subtitle nails it, “How to crush a generation and tell them they’re winning.” is a technology guy, but he’s refreshingly willing to point the finger at those living in his own house for their culpability in “‘Everyone Is Cheating Their Way Through College’ Who Should Bear the Costs?” has a dispatch from the AI front, his college and classroom that dispels the myth that everyone is cheating. offers us a wonderful reflective essay titled, “Why Write: Even if No One Will Read It and No One Is Sure What’s AI and What’s Human?” shares his presentation from the lions den of predatory ed tech, the ASU-GSV conference on why “AI Will Not Revolutionize Education.” takes on the too narrow question of AI and academic integrity and points the way towards a more productive way of thinking.And lastly (for now)

asks an important question, “What if AI Just Makes Everyone Really Boring?”And if you want to join me and a few hundred others for a month-long, collective discussion about writing and generative AI, you can sign up for the Perusall Engage event featuring More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI.

Links and Recommendations

It is Saturday, approach noon, and I really am quite weary and have run out of time to do the links and recommendations before I meet up with some friends I’ve known for 50 years or more that I don’t get to see all that often, so please forgive the omission of these usual features this week. I am, however, always seeking requests for those reading recommendations.

I will be seeing you next week.

All best,

John

"Is Big Balls, the notorious member of Elon’s Doge Army not already a fully realized dumbshit?" I'm dead.

I think my experience is different from some teachers because I have spent close to 10 years working with youth in informal educational environments rather than classroom settings, but the number of essays from teachers decrying students using phones all the time and not learning basic skills makes me sad because it seems to be true for many students in regular classes.

My experience in after-school settings and mentorship roles has been very different. I know so many young people who love discussing different topics and learning new things. When you ask them deep questions, they don't always give deep responses, but they do think hard and work through their reasoning process. I also know many who enjoy writing as a personal release or hobby.

I definitely had students who used their phones too much in my after-school program, but I also had students who were interested in their own learning and improving. And, after a certain time, interested in sharing thoughts they had been keeping to themselves. I believe much of this had to do with the informal nature of the program. Even on days when we didn't do "fun" activities, youth had bought in to the program and were thinking for themselves without needing to consider grades.

Soon I plan to write a post about our over-reliance on external motivation and how that kills the internal motivation students often naturally come with, or can activate with practice.