The New York Times’s multi-day feature on the “100 Best Books of the 21st Century” is obvious engagement farming that is clearly working - here I am writing about it - but I cannot yet decide if I am more interested or irritated by the exercise.

Maybe I’ll figure it out by the end of the newsletter.

The Times asked a bunch of book-related folks (writers, critics, Jenna Bush Hager, et al) to submit a list of up to 10 of what they believe to be the best books published since the turn of the millennium. Those ballots were tallied in some fashion and voila! Best books!

Released in tranches of 20 each weekday, we counted down to the “best” book of the 21st century which is, apparently, My Brilliant Friend, the first installment of the Neapolitan Tetralogy, by Elena Ferrante.

Fair enough. It’s not a ridiculous result by any means, and any of the top 10 or 20 in the final tally could plausibly rest in the number one slot. That said, it is incredibly irritating to find My Brilliant Friend being judged the “best” only to have it grievously mischaracterized in the editorial copy:

Uhh..what now? My Brilliant Friend is not “autofiction,” a genre associated with writers like Rachel Cusk, Ben Lerner, Sheila Heti, and the logorrheic Norwegian, Karl Ove Knausgaard (who surprisingly did not make the list), writers who essentially stream their lives as artists through a very thin filter and put it on the page as fiction. There’s not a darn thing wrong with it, I like many books labeled as autofiction, but autofiction and “autobiographical fiction” are not synonymous. If they were, we would have called almost everything Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, and others of their ilk “autofiction,” which we do not do. Given that we do not even know Ferrante’s identity, we couldn’t say if her novels are autobiographic fiction. They definitely are not autofiction. If you’re going to make a list for people to talk about, at the very least you should say reasonably true things about the book at the top of the list.

Chalk one up for irritation. Let’s just move on to the longer list of things that bug me.

Other Irritations

The methodology is absurd, which is fine because the question it is asking, to list the “best” books is absurd. The notion that we should combine fiction and nonfiction and poetry all-together in this evaluation is also dubious, but since there is no methodology for determining the “best” book anyway, it’s fine. I was not asked to participate, but had I been, I wouldn’t have turned it down.

Still, it’s dumb, and not in the self-conscious way as my beloved Tournament of Books because when the New York Times does it, it becomes capital-I Important.

There is an obvious recency bias to the selections that is understandable, but it would’ve been nice had it been mitigated against. It makes a list purportedly meant to represent almost a quarter-century heavy with books that are more trendy than enduring.

Jon Fosse’s Septology, clocking in at number 78, would’ve been entirely too obscure if not for a significant profile of Fosse by Merve Emre in The New Yorker, and Fosse’s subsequent Nobel Prize. It’s weird to think that a 650 page multi-volume novel written as essentially a single sentence benefits from being “trendy,” but I’m honestly surprised enough people submitting ballots had read it to amass enough votes to make the list.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin (published in 2022 and coming in at 76) is a compelling read that drew lots of fans, and I’ve recommended it to many people, but it is not a book that belongs near this kind of list and if you repeat this exercise in even five years, it will not be on readers radars.

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan is a small gem of a novel, but #41 on the greatest books of the 21st century? No.

George Saunders is an excellent writer and a mensch of a human being, but has he written three of the greatest books of the 21st century (Pastoralia #85, Tenth of December, #54, and Lincoln in the Bardo, #18)? I find Lincoln in the Bardo especially over-ranked. It’s an interesting and sometimes involving experiment that, to my mind, delivers very few pleasures as a novel, particularly relative to the man’s own short fiction.

Omissions are perhaps inevitable, and therefore innumerable, but how is Bel Canto, #98 (a perfectly cromulent book) on the list and there’s nothing by Louise Erdrich? Where is Sally Rooney? Rooney’s next book comes out later this year and she will be re-injected into our collective discourse. Had this happened prior to the voting, I bet you’d find her on the list.

The list is simultaneously spot on because there’s thousands of books that could be plausibly named in the top-100, and also a terrible miscarriage of justice because there is no such thing as justice when we’re operating in these realms.

I could go on, but I won’t. It’s probably unfair to gainsay any individual selection given the methodology and the impossibility of the ask of the voting panelists. Most of the books are quite good, many are great. Any assemblage would seem lacking and wrong.

I have fallen fully into the engagement trap the Times has laid for me.

Well played. And also curses!

Interests

The part of the project I’ve spent the most time on is perusing the published ballots of some of the voting participants. They’re an interesting lens for thinking about the intersection of individuals and books, the inverse of the aggregation represented in the lists.

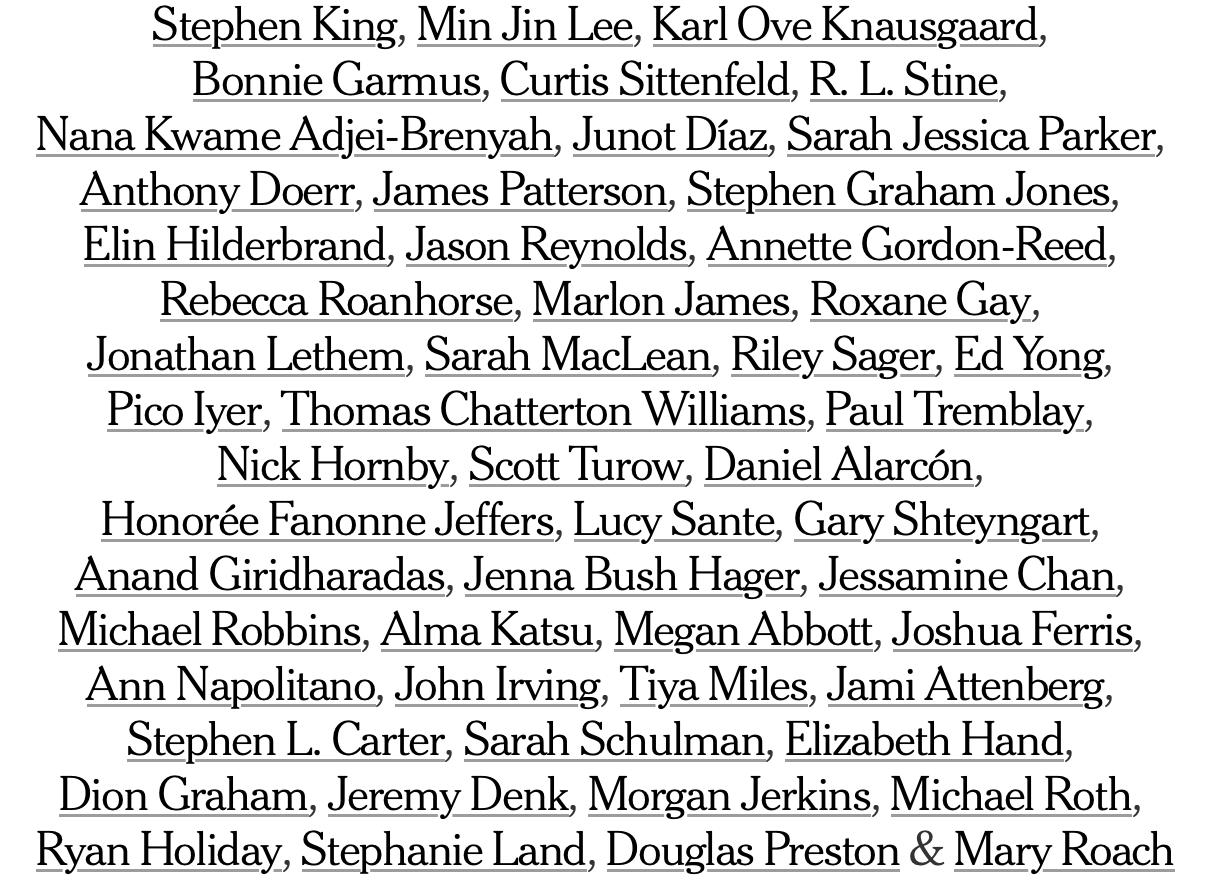

Off the top, it gives us some insight into who is in the Book Review’s rolodex:

It’s truly fascinating to try to suss out the mindsets of these folks based on their individual top-10 lists.

Of the authors represented, Stephen King (Under the Dome) and Stephanie Land (Maid) were the only ones who chose one of their own books for the top-10, an act of hubris so reflexively wrong to my midwestern sensibilities, I gasped when I saw it. Perhaps it is karmic justice that neither book wound up on the list.

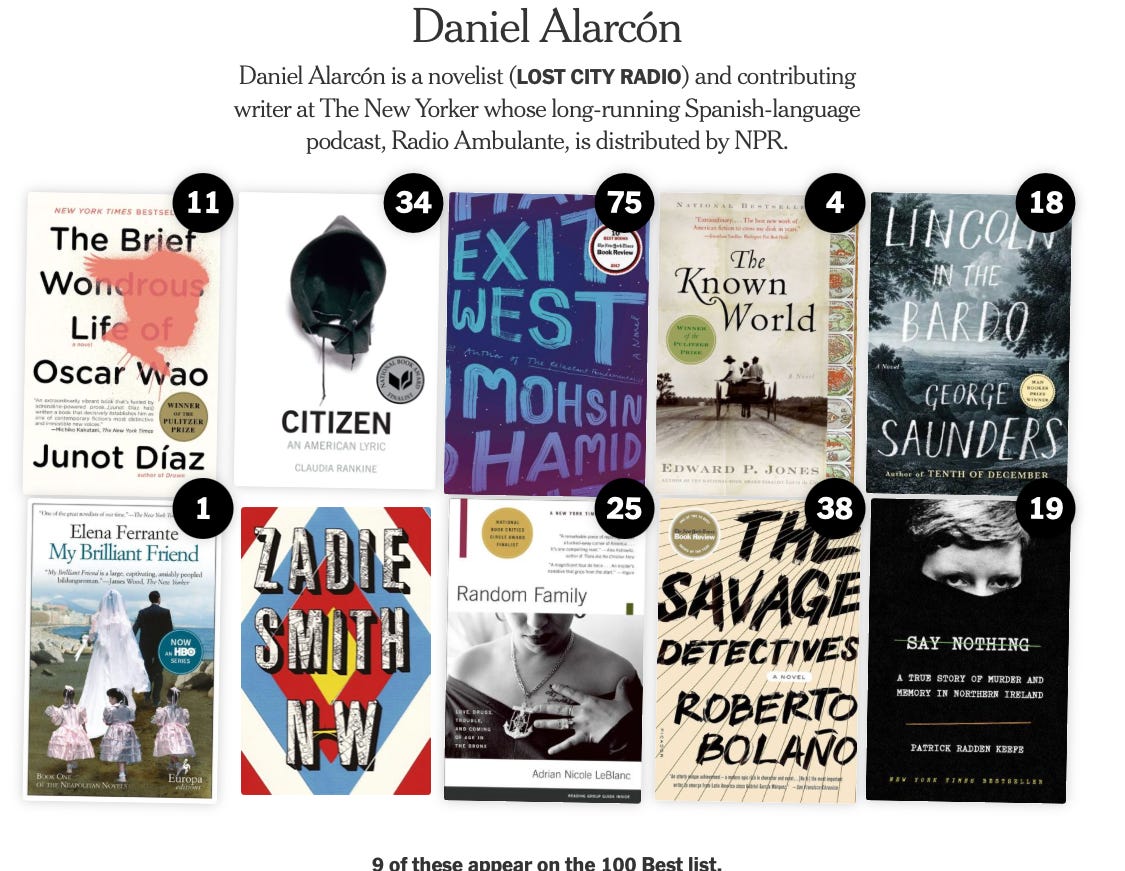

The participant apparently most in tune with the consensus is Daniel Alarcón, who had 9 of his 10 selections wind up in top 100.

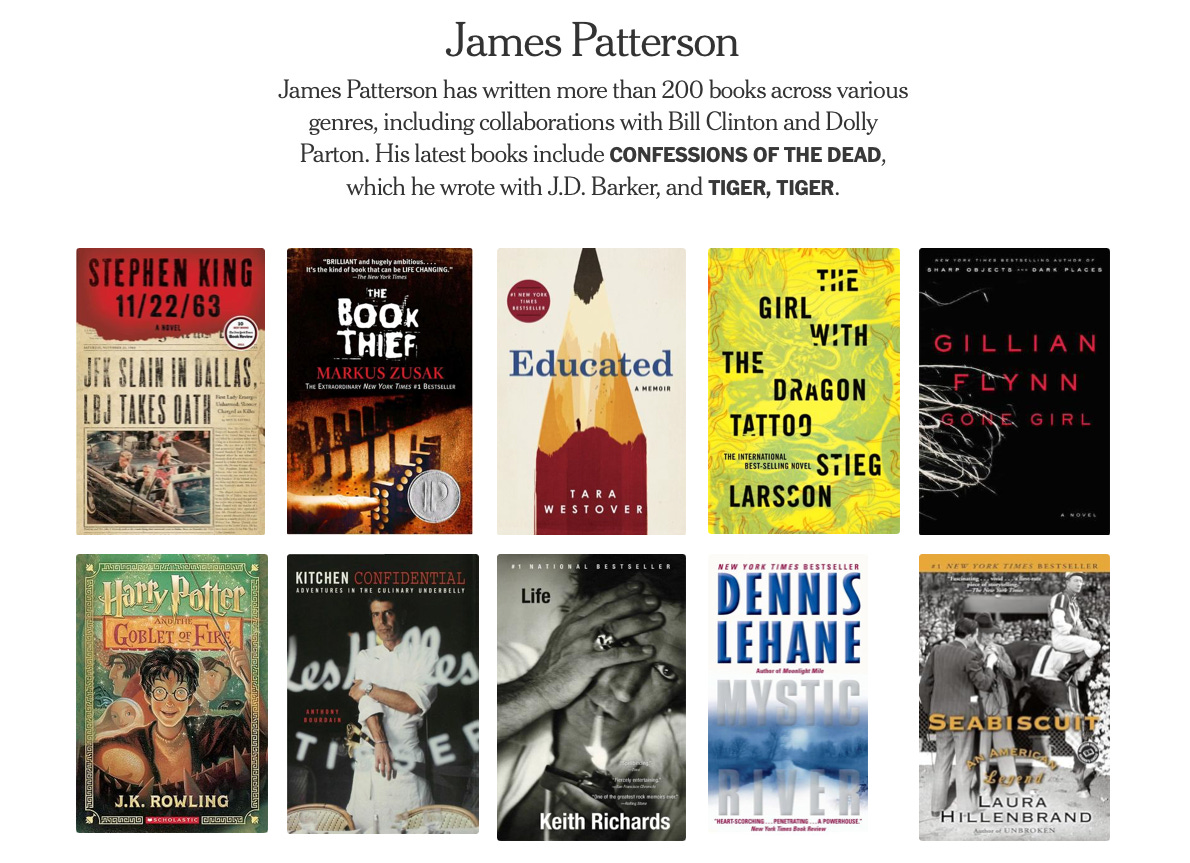

A bunch of participants had zero of their top-10 selections show up in the top-100. It’s clear that coming from a non-literary genre leaves one out of step with the ultimate consensus. James Patterson drew a goose egg.

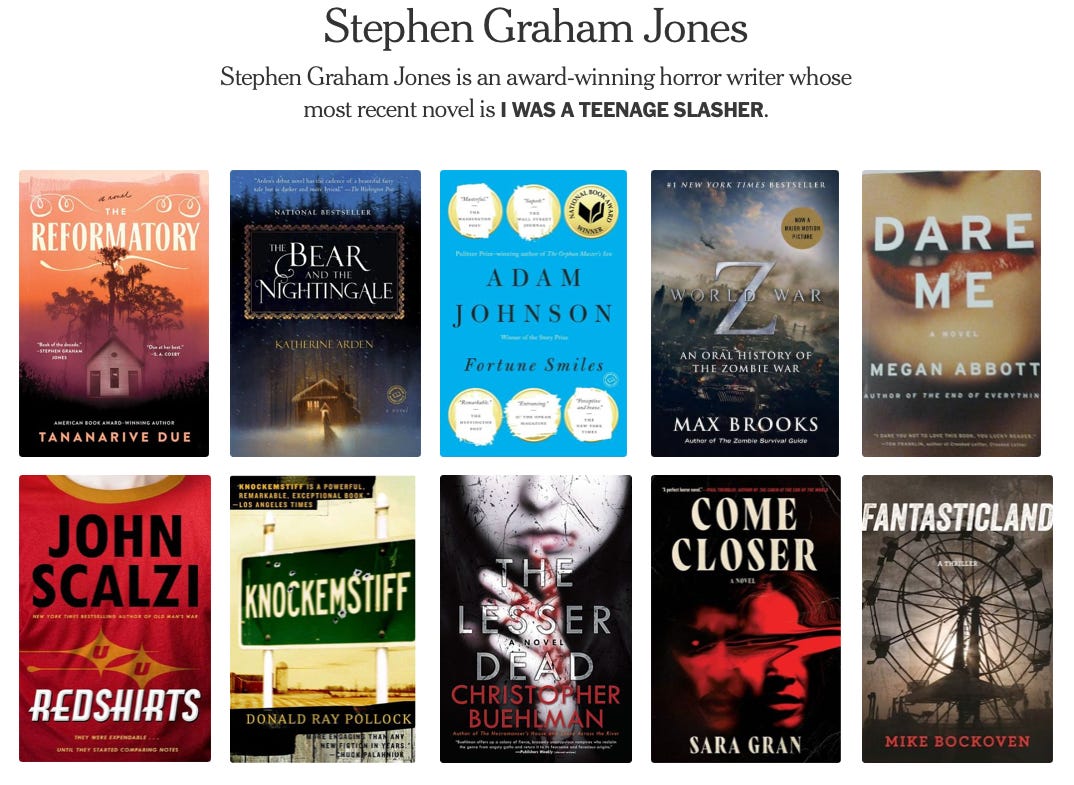

As did Stephen Graham Jones:

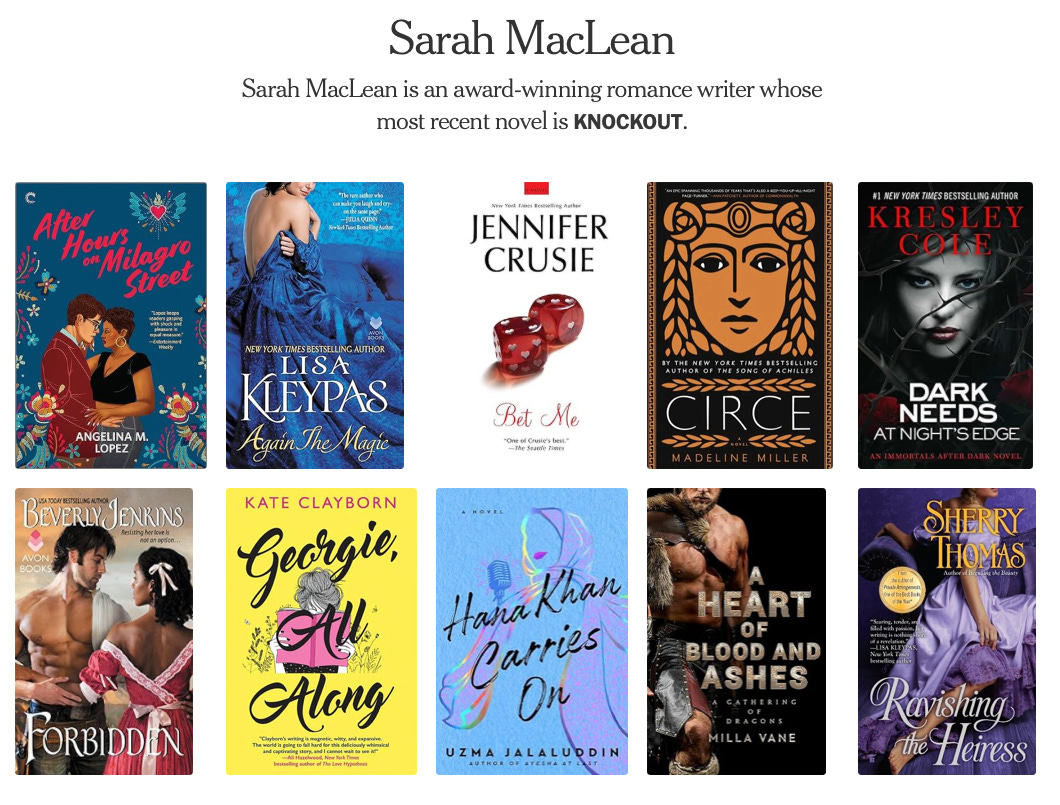

Sarah MacLean, a romance writer, also batted .000 with books, aside from Circe, that never had a shot, which is why I so appreciate the inclusion of these lists as a way to appreciate the diversity of views with which we consider a question like “What are the 10 best books of the century?” The aggregating of all these subjective ballots into a single list gives a veneer of objectivity. Seeing the diversity of some of the individual participants reminds us of that underlying subjectivity.

It was personally fun to see the books of some friends pop up on the lists, including the expected, Dave Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, and the more surprising, Pitchaya Subanthad’s Bangkok Wakes to Rain, which was recommended by Gary Shteyngart.

The other interesting experience was to go through the lists and see books that I’d never heard of, but were someone else’s favorite. For nonfiction, these titles were numerous, but for fiction, they were very rare. One, from Bonnie Garmus’s (Lesson’s in Chemistry) that stood out was Pobby and Dingan by Ben Rice, which rang zero bells for me.

It might be an interesting exercise to try to come up with a personal list of ten best books that you think most other people would be unfamiliar with, or are unlikely to wind up on someone else’s list.

Submit your own list

The Times has set up an interface where you can submit your own 10 best books. While I would’ve participated had I been asked, despite much time contemplating my entry, I have yet to settle on a collection of ten that satisfies me. Every inclusion results in an omission, which sends me back to wondering how I’m defining “best.”

Is it my “favorites?” The books I find most “meaningful?” The books I find most “important?” For example, Gone Girl is a book I enjoyed that is also culturally important for the way it recast the domestic suspense genre. Do I give it extra credit for that influence, or do I just stick to the books I think are “the best”?

I’m tying myself in knots here. Don’t even get me started on how to weigh the relative merits of fiction versus nonfiction.

Maybe I’ll get it together and participate in the collective fun, or maybe my fun is in continuing to consider all the ways I remain irritated.

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I covered Adam Moss’s The Work of Art: How Something Comes from Nothing, which I’m declaring my “gift book of the year,” even though it’s only July.

also includes The Work of Art in his collection of the best stuff he’s intersected with this year.In other John Warner create’s content news, at my

newsletter, I interviewed Susan Blum about her new book, Schoolishness: Alienated Education and the Quest for Joyful Learning. At Inside Higher Ed, I explained how venture capitalists who call things like lesson planning and reading student work “the basics,” and therefore amenable to being outsourced to AI are wrong. Those things are “the fundamentals.”Many of you have probably heard the story of Andrea Skinner, the daughter of Alice Munro who published an essay detailing the sexual assault she experienced at the hands of Munro’s husband, Gerald Fremlin, and the fact that Munro sided with Fremlin over the abuse, while many others who knew of the abuse did and said nothing. If you’re looking for perspective, in addition to Skinner’s essay, I can recommend this reflection from Brandon Taylor, and this piece from Jonathan Eig, about how biographers owe it to their subjects to be honest.

At Esquire, Kate Tobin writes about what she perceives as the absence of “sad boy novels.”

has three interesting thoughts of his own about The New York Times list, including wondering where all the young writers are. At, , Hornby offers some inside scoop on how he chose the books on his list.This week via McSweeney’s, and courtesy of Jeff Steinbrink, “William Faulkner Does Pickleball.”

Recommendations

1. James by Percival Everett

2. Real Americans by Rachel Khong

3. Butcher by Joyce Carol Oates

4. Table for Two by Amor Towles

5. Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Cynthia S. - Garland, TX

My Education by Susan Choi is a novel about real, and really messy people trying to make sense of their desires, infused with Choi’s signature sly wit.

1. The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

2. Democracy May Not Exist But We'll Miss It When It's Gone by Astra Taylor

3. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman

4. John Woman by Walter Mosley

5. Diary of A Void by Emi Yagi

Megan C. - Anchorage, AK

One of the more surprising titles on the Times top-100 is Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, which I think is a good fit for Megan.1

I’m making a vow to myself to turn away from the endless loop of cable news and my social media feeds gnawing over yesterday’s horrible events, and instead read a book. Is this escape? If so, so be it.

Take care,

JW

The Biblioracle

All books (with the occasional exception) linked throughout the newsletter go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and an additional reading/writing/literacy nonprofit to be determined. Affiliate income for this year is $79.00.

FWIW, and possibly for your amusement:

As one of the invited respondents (though not fancy enough to have my list, which I don't entirely recall anymore, publicized):

I made my way to ten inarguably (at least not if I'm arguing with myself) great books that I truly loved (my sole criterion: I'd actually read them), mulled it over, and pressed the button. The notion of picking the ten best of anything strikes me as impossible if you don't actually know all the candidates.

A few of my selections ended up on the top 100 list (yay, me, I guess).

I also named at least two books published in 2000, which as far as I'm concerned is a year of the last century, but that's an issue for another day.

"The notion that we should combine fiction and nonfiction and poetry all-together in this evaluation is also dubious."

Completely agree with you here, and would like to point out that the NYT list also includes two (I think) comic books/graphic novels as well.

I'm really not sure how, to use two books that made the final list, how one assesses whether Cormac McCarthy's The Road is better or worse than Tony Judt's history of postwar Europe; the authors just seem to be pursuing completely different aesthetic goals in their books.