I was introduced to Beth Kephart’s work by Cassie Mannes Murray, who has reliably smart things to say about publishing in her newsletter. If you’re interested in nuts-and-bolts bookish stuff—the life of a bookstore events coordinator, for example—then Cassie’s Substack is the place to be.

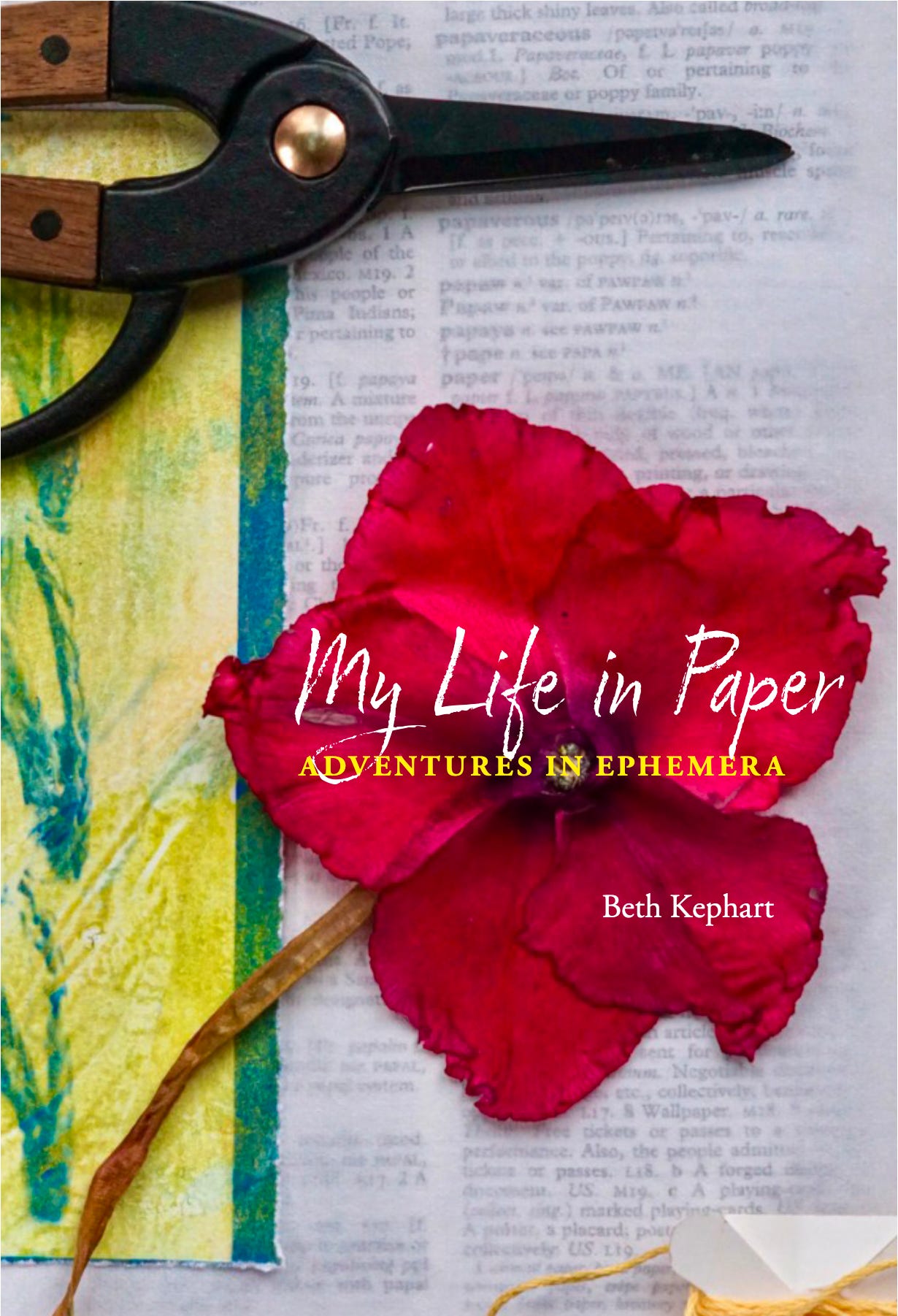

Cassie knows exactly which people to connect, and I’m so pleased that she brought Beth Kephart to my attention. A National Book Award finalist, Beth is the author of (among many other titles) My Life in Paper: Adventures in Ephemera, coming from Temple University Press this fall. It’s a memoirist’s guide to the role paper plays in our construction of ourselves. Head to Edelweiss to request a review copy.

Beth’s many talents extend to book arts, and—in the sort of collaboration I love about university-press publishing—she designed the cover for My Life in Paper.

Here she recommends work by Judith Kitchen.

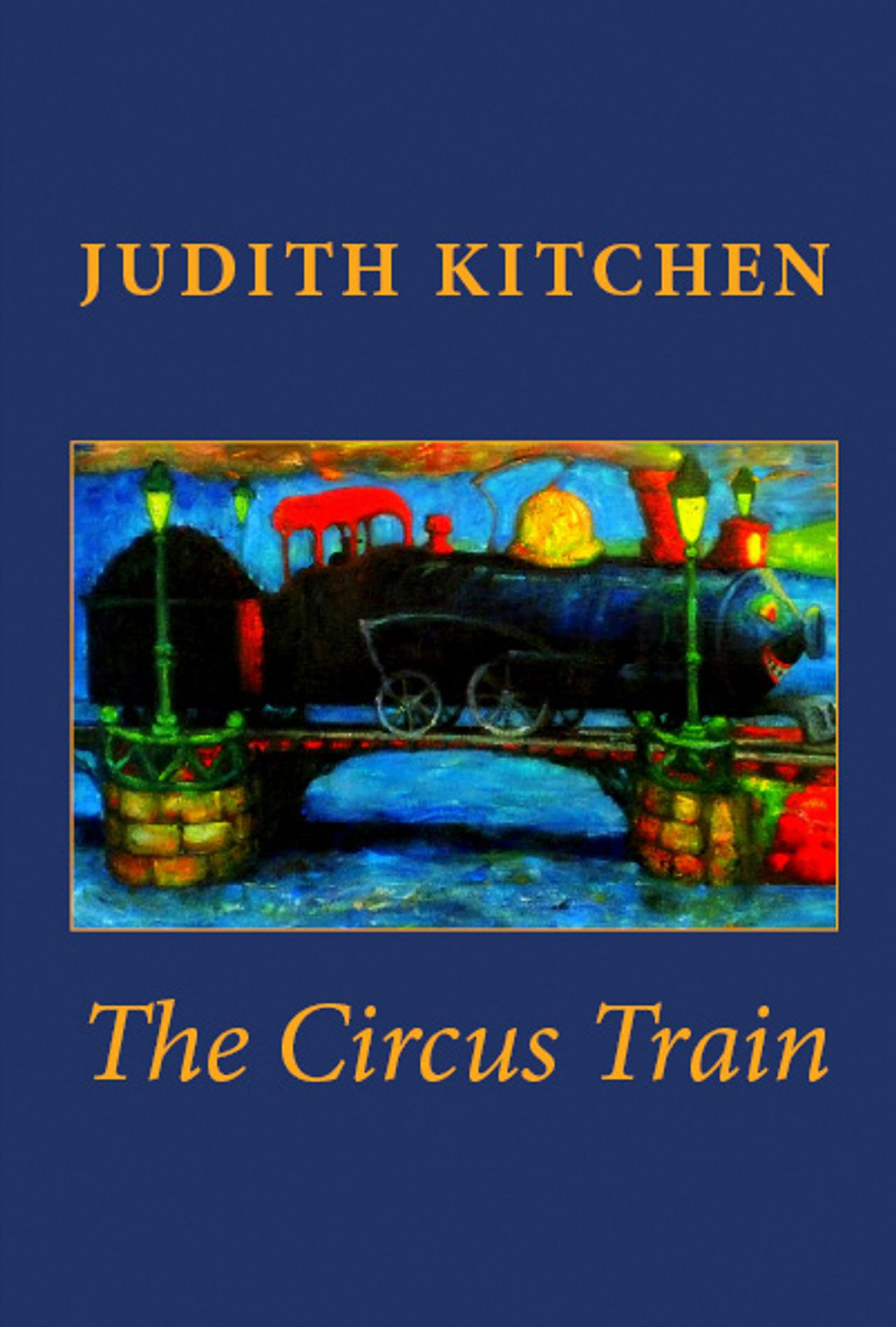

A Book I Wish More People Knew About: Beth Kephart on The Circus Train by Judith Kitchen

I wake from a dream in a which a dark-haired woman is tossing fireworks toward the sky—bursts upon bursts of color; exotic geometries—and I imagine, in the quiet early hour, that my mind is rehearsing the tale of Sophie Blanchard, that phenom lady balloonist who, in the early nineteenth century, would cast fireworks from her aloft perch to awe the crowds below.

But then the haze that was near-dawn becomes the light of the new day, and I realize that Sophie Blanchard was not, in fact, the agitator of my dreams. That honor goes instead to Judith Kitchen, whose words I was just yesterday urging toward a gathering of soulful writers. They are the words from Kitchen’s last book, published in 2013 by her own press—Ovenbird—just before her death from cancer in November 2014; she was seventy-three. They are the words that have continued on for those lucky enough to have found them—fresh and seductive, clean alive.

I looked up, and there it was—the little circus train winding through the valley.

The Circus Train is, like Kitchen’s Half in Shade: Family, Photography, and Fate and Abigail Thomas’s memoirs Safekeeping and Still Life at Eighty, a book of spectacular flashes, which is to say fragments. Circus comprises a long segmented essay followed by two separate shorter works. Each small piece is a spark, a shattering of color, a frisson of idea. Nearing her death, the writer is reaching back through time. Her remembering is vivid but not precise. Some pieces of her puzzle do not fit. Some do not accord with history.

Take that circus train that huffs through memory. What to make of it?

But was there a valley? I don’t remember that there was. There were cornfields, and beyond them the woods. And the river on the other side of the road. But I remember the train, far away, while I was sitting in the strawberry patch. It must have been another time, another place. But there it is: the blue and yellow and lavender cars following the tiny plume of smoke, rounding a bend, suddenly emerging from a string of trees . . .

Kitchen sees “so clearly,” and “still there is doubt.” She knows for certain what the train brought with it—the clowns, the elephants, the tightrope walker. But perhaps it would help to take a step back, to look upon the past in the third person. And so she does:

Memory serves her well. And yet here, caught on the brink of its own oblivion, it deserts her at a crucial moment. That train has lived in the folds of her brain for well over half a century, and only now, when she wanted to write it down, did it disappear into ripples of doubt.

Kitchen’s negotiations with herself against the backdrop of a loudly ticking clock have always struck me as intrepid. She uses the time that remains to be as particular as she can. To be curious. To be purposeful. To be present. To be honest. To interrogate herself just as she yields to herself—interrupting one memory with another, returning to the present hour when the present hour strikes.

Kitchen’s capacity to follow the mind as it moves—the distilled image, the surprising question, the quotidian wish, the white space, the white space, the white space, the wanting to be sure and yet so valiantly unsure—is just one of many reasons why I wish every writer might find this book, read it, and keep it safe within their shelves. Inside The Circus Train are instructions on how rich and dimensional the truth can be, how fantastic as fiction, how propulsive and compelling. There are lessons, too, on the longitudinal power of the sequenced parts. Lessons on the many magnitudes of flashes.

But I have bigger ambitions for Judith Kitchen’s final book. I’m rapacious as they come, when it comes to books I love: I want a copy of The Circus Train for every human being who is now or who may someday be grappling with memory and wish, gratitude and desire, the present moment and the coming hour. I want the book for any human wondering what being human really means. I want it for anyone who is willing to be dazzled, for anyone who stands, looks up, and sees.

Beth Kephart is the author of many books in multiple genres, an award-winning teacher of memoir, co-founder of Juncture Workshops, and a book artist. Her book My Life in Paper: Adventures in Ephemera is due out in November from Temple University Press. More at bethkephartbooks.com.

Previously in “A Book I Wish More People Knew About”

Vol. 1: The Actual True Story of Ahmed and Zarga, recommended by Phyllis Mann.

Vol. 2: Laura & Emma, recommended by Teddy Wayne.

Vol. 3: The Woman Lit by Fireflies, recommended by Christine Sneed

Vol. 4: This. This. This. Is. Love. Love. Love., recommended by Casey Plett