For a number of years, one of my great pleasures was to co-judge the McSweeney’s Column Contest with McSweeney’s Internet Tendency editor Chris Monks.

We’d put out a call, 1500 or entires would show up and Chris and I would read and discuss and debate and decide on five columns that would run for a year on the site, and that I would edit.

Our method was to independently narrow our lists via an initial culling to “Yes” “No” and “Maybe.” The No’s numbered in the thousands. The Maybes were in the twenties. The Yeses never numbered more than a handful. Every year, there were one or two columns that hit both of our Yes columns without any consultation with each other.

One of those years, a column titled “Balls Out: A Column About Being Transgendered” by Casey Plett had two enthusiastic Yeses out of the gate, and became one of our selections.

This was 2010, a lifetime ago it seems when it comes to the trans experience being represented in mainstream publications and literature. We’ve made so much progress since then, and now because of that progress, because some people are threatened by progress, there is a rather ugly backlash at work.

Ever since first reading “Balls Out” in our contest inbox I’ve been a fan of Casey Plett’s work, and have been excited to see it getting the attention it deserves, and I thought she would make a great person to ask about what book she thinks deserves more attention.

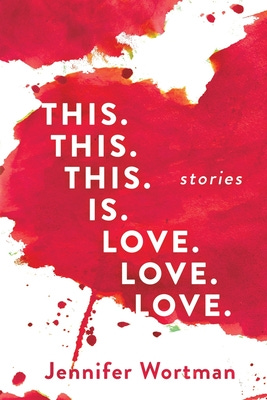

A Book I Wish More People Knew About: Casey Plett on This. This. This. Is. Love. Love. Love. by Jennifer Wortman

I encountered Jennifer Wortman's fiction in quarantine life of May 2020. Alex DiFrancesco had linked to her flash fiction piece, “A Person's Essence Feels the Smallest.” Like many, in that time I had enormous difficulty focusing on fiction—I did the proverbial doomscrolling and had gone back to playing video games, a childhood pastime I tend to revive in times of deep rift.

In “A Person's Essence Feels the Smallest,” published in wigleaf, a woman is sitting in a driveway with her new boyfriend (or rather, I'm choosing to call him her boyfriend, the story just calls him “this man”). The two of them are about to go see the woman's mother, so the mother can meet the new boyfriend, but then in the driveway they get into a fight about something hilariously stupid and also deeply serious, and she leaves.

I read the story in minutes and immediately ordered This. This. This. Is. Love. Love. Love. And if I had to pinpoint the vector in which literature began coming back to life to me in the pre-vaccine era, it was with reading this book. I read it slowly over that summer. And it hurt. But it was good. Wortman's ability to portray psychic damage, addiction, mental health catastrophe, loneliness, destructive relationships—it's close to perfect. I had a writing teacher once who said, “Don't forget readers only read one word at a time,” which sounded like a truism at first but soon revealed itself as wise advice that I find rarely mastered in most of what I read—and when writers do understand it, they get cute with it. Not Wortman though.

From the first story in the book, “Love you. Bye.” where the narrator is describing her boyfriend's work representing abused children:

At home, at all hours, he takes work calls in both English and Spanish, and either way I understand just enough to know I understand nothing. Though I ask and ask, he won't tell me what he's discussed. This is another reason I love him. In fact, I love him so much that he's not just my boyfriend. He's my fiance—though I have a hard time calling him that, for fear of cursing us both.

What he does tell me about his job: It's important, when possible, to keep families together. But sometimes it's not possible.

The context is that the narrator is attracted to the young man who helped her get her first smartphone, whom she resolutely refers to as “the phone boy”. The phone boy plays in a band, and the narrator's going to one of his shows and she invites her boyfriend to go with her, but the boyfriend can't because of his job. The narrator invited him precisely because of her twin feelings for the phone boy and her love for her boyfriend. She explains she invited him: “to protect that love from the new excitement taking over my brain. Deep down, though, I also crave the charge of having him and the phone boy in the same room. I am a terrible person, and worse still because though I genuinely want him to come to the phone boy's show, I'm also genuinely thrilled he can't.

“Love you,” I said. “Bye.”

The steady undertow in much of life of doing self-destructive shit you know is bad, that is not healthy, that you know you shouldn't do and you also are abso-fucking-lutely going to do anyway, reliably and unquestionably as rising every morning to go to a job you hate—I read a lot of fiction that attempts to touch on that steady undertow, and much of it falls flat, but Wortman gets it, for me. She paints lives freighted with grief and depression and addiction and she does it with quick, light, undramatic touches, and a strong undeniable voice that carries the reader firmly forward.

I read the last story in the book, “Explain Yourselves,” having just moved back to New York City in late summer of 2020, in the wake of another episode of my own personal drama that involved me ripping up a life and starting over. I finished it on the subway. “Explain Yourselves” is about a forty-one-year-old divorcee named Ken who's fixed his life and is going back to school. Ken takes a course on Southern literature, and on the first day, the young domineering female professor asks everyone why they're taking it. (Hence the title “Explain Yourselves.”) Ken tells the class, “that a few years ago, I quit drinking and found God, and it seemed like the literature of the South would have something to say to both the drinker and the believer in me. There was an uncomfortable rustling in the room.”

Slowly, Ken becomes infatuated with the professor, until their interactions end in a way that's at once surprising, inevitable, and deeply sad. He also reveals how his marriage ended, right after he quit drinking and found God.

I no longer left Georgie alone every night. I stayed with her, cooked for her, helped her clean. I cut coupons from the newspaper, and if she wanted chips, I got them from the kitchen so she could stay in front of the TV. And that's when she left me—when I'd become her husband again. She'd left a note on the kitchen table. “The love's gone,” it said. But that kind of love, the love you miss, had been gone for years. I understood then that what she really yearned for was the freedom of my drinking days, a freedom I'd mistakenly thought of as just mine, and no longer craved.

This is what I love so much about Wortman's work—the way good-hearted humans undramatically destroy their own lives and each other, and about how meaningless being good-hearted can sometimes be. This. This. This. Is. Love. Love. Love. is both extraordinarily heavy yet has the lightest touch, in the manner of a still sunny winter day. I cried finishing it in my near-empty subway car, still learning to touch my fingers to a new dead world, and I felt gratitude for the way that somehow, paradoxically, all the hurt and damage the book contained could still kindle life regardless. I was lucky to encounter Wortman's writing, and I hope if you read it that you are too.

—

Casey Plett is the author of A Dream of a Woman, Little Fish, A Safe Girl to Love, the co-editor of Meanwhile, Elsewhere: Science Fiction and Fantasy From Transgender Writers, and the Publisher at LittlePuss Press. She has written for The New York Times, Harper’s Bazaar, The Guardian, The Globe and Mail, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, the Winnipeg Free Press, and other publications. A winner of the Amazon First Novel Award, the Firecracker Award for Fiction, and a two-time winner of the Lambda Literary Award, her work has also been nominated for the Scotiabank Giller Prize. She splits her time between New York City and Windsor, Ontario.

Previously in “A Book I Wish More People Knew About”

Vol. 1: The Actual True Story of Ahmed and Zarga, recommended by Phyllis Mann.

Vol. 2: Laura & Emma, recommended by Teddy Wayne.

Vol. 3: The Woman Lit by Fireflies, recommended by Christine Sneed