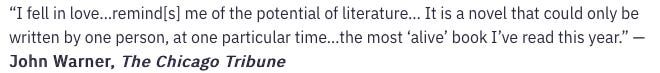

While doing the back and forth with Derek C. Maus on “understanding Colson Whitehead” I was trying to better understand what it was that so immediately, personally compelling about Whitehead’s first novel, The Intuitionist, when I read it not long after it was released in 1999.

For sure, Whitehead starts with an attention-grabbing first line:

It’s a new elevator, freshly pressed to the rails, and it’s not built to fall this fast.

…but writing an attention-grabbing first line is hardly sufficient for the depth of engagement and pleasure that reading the novel delivered for me. Truly connecting with a novel is, and I don’t say this lightly, an act of intimacy. There’s a quote from George Saunders that he shared in a message board Q&A in the old Salon Table Talk interface sometime in the late 90s that I’ve been carrying around ever since that captures what I’m talking about. (Emphasis mine in the coming quote.)

I think what any of us pays for when entering into a reading experience is that feeling of seeing another mind at work, and not at work in a rational way. There’s something grilling about seeing this other mind at work in this blissful and private and self-referential way, and then suddenly your mind joins it. How weird and inexplicable that is. There’s a sort of knowledge that goes beyond our mundane everyday knowledge. The reader and writer are being smarter together than either one could be separately.

…suddenly your mind joins it. Yes. That’s it.

This joining does not happen with every book, or most books, or even some books I could tell that I “liked” and are “good.” We’re talking next level stuff, and ultimately on some level, it is “inexplicable.”

This isn’t to say it’s entirely unknowable or the product of some kind of magic, but when it’s happening, it’s a sensation, not something we can rationally grasp.

What we’re experiencing in these moments is an encounter with what I call a “unique intelligence.” As it happens, every single one of us is a unique intelligence, it’s just that not everyone is capable of transmuting that intelligence into a text that achieves this kind of connection.

In theory, given that large language models, in a way, join an unfathomable number of minds together when it goes about fetching its syntax in response to a prompt, one would think that its outputs are many times more potent in terms of engendering this kind of connection. If two people together are smarter, a gazillion people together should be smarter still.

Except it doesn’t work that way. Syntax is not the full product of human cognition. A billion voices boiled down is not nearly as interesting as a very specific other voice.

In this age of artificial intelligence, I’ve made my bet that developing and expressing one’s unique intelligence is a differentiator and that people - at least the people who read - will gravitate toward these folks. This isn’t a difficult bet, given this is how readers have always behaved, but the existence of a text-spewing machine that takes those unique intelligences and brings back a flavorless slurry - or in the case of some models that have been trained to have a “personality” - a creep show simulation of a unique human intelligence, we can appreciate these qualities anew.

Some writers just have the juice and in some cases, that fact was obvious to my subconscious from the get-go. Colson Whitehead is one of them. These are some others.

In my recent Chicago Tribune review of Weike Wang’s latest novel, Rental House, I explicitly said that Wang had the juice, and it was apparent to me with her first novel, Chemistry, which is written in a completely winning comedic dead pan. The story of a first-generation American PhD student of Chinese dissent who is struggling with trying to figure out what she wants in life, Wang’s humor smuggles in deep feeling.

The opening of Kiese Laymon’s Long Division, the story of Citoyen “City” Coldson crackles with energy and made me laugh three times in the first paragraph. Satire, metafiction, time travel, the legacy of Jim Crow, Laymon stuffs this novel with everything imaginable.

That Yaa Gyasi published a novel with the scope and complexity of Homegoing at age 27 is mind blowing. Homegoing follows eight generations of a family from present-day New York back to the origins of the African slave trade. I’ve recommended this book at least a dozen times and it’s never disappointed.

A Brave Man Seven Storeys Tall by Will Chancellor takes an Olympic-level water polo player felled in a freak accident into the depths of the Berlin art scene and a series of unlikely and uncanny adventures. This is what I had to say in my review, later extracted for promotional purposes by the publisher.

The protagonist of And Now You Can Go, Ellis, a graduate student taking a break on a park bench, is soon accosted by a man who is enlisting her in a kind of murder suicided. By reciting poetry she’s memorized she manages to escape with her life, but the incident leaves her understandably unmoored. She spends the rest of the novel searching for the equilibrium she lost, but also maybe never had. Vida’s novels - including Let the Northern Lights Erase Your Name and We Run the Tides - are quietly brilliant explorations of the intersection of women and a world that simmers with hostility.

Now, other folks might read these same novels and wonder, What’s the fuss?, but that’s the thing about unique intelligences. Not all individual pieces fit together. That’s what’s great about all of this.

Now, what writers did you know had “the juice” from the start?

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I espouse the significant virtues of

’s literary biography, The Many Lives of Anne Frank. Watch out Tuesday for a special Q&A with the author as bonus Biblioracle Recommends material.At Inside Higher Ed, I wrote an appreciation of the work of composition scholar and giant of teaching writing, Peter Elbow, who recently passed away.

Elon Green has a fascinating piece on the lost play of Toni Morrison.

Kathryn Stockett published The Help to massive sales and also significant criticism 15 years ago. Her follow-up novel will come out next year. This piece prepares the ground for what is sure to be a significant promotional push.

Via

and by the unique intelligence of Danniel Rodriguez, “Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the Last Two Weeks.”And Again, ICMY, check out my Q&A with author of Understanding Colson Whitehead, Derek C. Maus:

Recommendations

1. Nazi Literature in the Americas by Roberto Bolaño

2. The October Country by Ray Bradbury

3. Other People’s Trades by Primo Levi

4. Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights by Salman Rushdie

5. The French Lieutenant’s Woman by John Fowles

Connie B. - Glen Ellyn, IL

I think Connie is an excellent candidate for the works of W.G. Sebald. The specific recommendation is Rings of Saturn.

1. Aspects by John M. Ford

2. The Dawn of Everything by Graeber and Wengrow

3. Luna trilogy by Ian McDonald

4. The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes

5. The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

Scott M. - Des Moines, IA

For Scott, I’m taking inspiration of an author from Connie’s list, but choosing a different book, The Magus by John Fowles.

Will I tell you, yes you, what to read next with a pick drawn not from an algorithm, but my own unique intelligence? I will. Click that button to see how to request your recommendation.

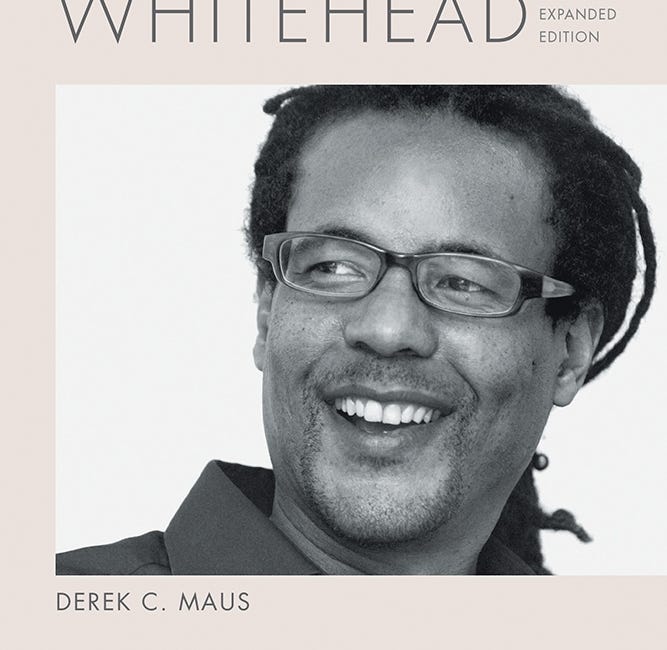

A good week in John Warner’s world. The audio rights for More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI have sold, and also, I made this reader cry (in a good way) when she was reading my book.

Additionally, Tim Riley the curator for America’s National Churchill Museum in Fulton, Missouri sent me this picture:

That’s kind of cool. Also kind of cool is that after the usual first week of sales spike and the subsequent second week fall, it looks like weekly sales of the book are trending up. It also seems like the people who are reading the book are connecting to it. Unique intelligences for the win.

Thanks for your attention this week, and remember, good stuff coming Tuesday.

JW

The Biblioracle

One interesting characteristic of the juice, in my experience, is when you pick up a book about a topic or characters that you normally wouldn't find compelling, read a bit, and realize that you're going to finish the book as soon as you can, it's just that good. My Brilliant Friend was that sort of novel for me - I was going through the NYTimes top 100 list, realized that I'd read pretty much everything else in the top ten, and decided that I should give it a try, and wow, while it's not my very top favorite of the 21st century, I really enjoyed it and read it very fast (overdue status at the library being a secondary motivator).

I just finished reading The Last Samurai by Helen DeWitt and I’ve never felt quite the same way reading a book as I did with hers. Filled me with joy at being alive to have read it.