I have never been afraid of Black excellence. In fact, it’s something more like the opposite. I have been fascinated by Black excellence because when the excellence appears it is often so obvious, undeniable. In contrast, as a white mediocrity, the excellence of my fellow white folks needs to sometimes be explained to me because it looks awfully familiar, and not all that interesting.

These thoughts are spurred by watching Amir “Questlove” Thompson’s recent documentary on Sly Stone, Sly Lives: The Burden of Black Genius. One the one hand, the film follows the music documentary formula to work through the life and music of Sylvester Stewart/Sly Stone, for a short period the most popular musical entertainer in both white and Black America.

On the other hand, Questlove uses the life of Sly Stone to examine the relationship between America and Black genius. The overtly stated question “What is Black genius?” makes room for the unstated corollary, “And why can’t America handle Black genius?” to hang over the entire film.

Near the start of the film, from off-camera, Thompson offers a theory about the additional burden Black artists who achieve great fame and public recognition must navigate as Black people, and that Sly Stone was one of the first to be saddled with this burden. Thompson asks some variation on the question - “What is Black genius?” to a handful of certified Black geniuses (Maxwell, Chaka Khan, George Clinton, Nile Rodgers, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis). They are apparently sufficiently stumped that the camera does not wait long enough to see if there is any response until Andre 3000 pauses briefly and says, “I love it when it happens.”

Me too. I wish I could take credit for my apparent enlightenment, but we’re talking about an internal wiring over which I do not perceive any great influence or control. It is a little mysterious, particularly considering I grew up in a highly segregated Chicago suburb where almost everyone was white and there were never more than half-a-handful of Black students in my high school at any given time.

While I am certain I house some measure of the usual prejudices and ignorances around race, I also know that my experiences of the art of of Black geniuses are overwhelmingly the most profound artistic experiences of my life. While watching Sly Lives, as Thompson showed a series of live performances of Sly and Family Stone, I teared up in my kitchen marveling at the beauty of this genius. I don’t know why anyone would not, the music is so profoundly and self-evidently wonderful.

I understand that this all risks coming across as a form of self-congratulation, as I pat myself on the back for my colorblind open-mindedness, but that is not my intent at all. I’m talking about my wiring, not something I’ve worked at or developed. I deserve no credit or congratulations.

What is going on here?

—

Part of it is that I while I was raised in an all-white suburb, the music in my house was Black. My father, a white man born in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1941 had no great affinity for white rock and roll. My older brother and I once pulled out his copy of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band from the shelves and the cellophane was still wrapped around the sleeve; the record looked pristine. His music was soul and R&B, first artists like The Coasters and Sam Cooke, and then Motown, of course. Radio station WGCI, Chicago’s “Black” station, was his preferred listening.

To this day, if I listen to Marvin Gaye Live at the London Palladium, I could tell you the exact point where on the 8-Track version, “Got to Give it Up” would fade out so it could switch to the next track.

Like any other suburban white kid in the 1980s I did my time with Rush, Genesis, AC/DC (the 5th grade boys thought the one-and-a-half entendre of “Big Balls” was the cleverest thing ever), but the music I was raised on always lurked. I never stopped listening to Marvin and Stevie Wonder, and then Prince.

Remember Terrence Trent D’Arby? I don’t know if he was a genius, though TTD thought so of himself. I would’ve told you he was my favorite musician at the end of high school while Def Leppard was the preference of most of my compatriots.

Not my friends, we had good taste, including the good sense to recognize the genius of Sly Stone as made manifest in the Woodstock documentary that I first watched on Chicago’s pre-cable subscription television service, OnTV.

While I was raised in that nearly all-white suburb, I was also raised without obvious prejudice. My parents sent me to an integrated summer camp so I could spend at least some time with non-white kids. It’s also not particularly hard to respond positively to great music. To listen to Songs in the Key of Life and not hear profound genius it to lack something essential in your being.

The Beatles were great, but later on, when I first heard Chuck D and Flava Flav rap in “Fight the Power”:

Elvis was a hero to most But he never meant shit to me you see Straight up racist that sucker was Simple and plain Motherfuck him and John Wayne 'Cause I'm Black and I'm proud I'm ready and hyped plus I'm amped Most of my heroes don't appear on no stamps Sample a look back you look and find Nothing but rednecks for 400 years if you check

I couldn’t exactly identify…but I did agree! Elvis just kind of sucked, simple and plain and corny and lame. John Wayne too, for that matter.

—

Growing up a Chicago sports fan of that era also meant my athletic heroes were Black geniuses, first Walter Payton, then Andre Dawson, and then Michael Jordan, but also loved the not quite geniuses, the pre-Jordan Bulls: Norm VanLier, Orlando Woolridge, Artis Gilmore, and Reggie Theus. I thought Chicago Bears wideouts James Scott and Ricky Watts were two of the greatest receivers in NFL history. They finished with 177 and 87 career receptions respectively.

It’s possible I’d fallen prey to some sort of exoticising of these athletes because I had no direct familiarity with Black people, but I just thought they were great. When I was in grade school I lamented every game when rifle-armed Bears quarterback Vince Evans was left on the bench in favor of Bob Avellini who could barely throw an out to the sideline.

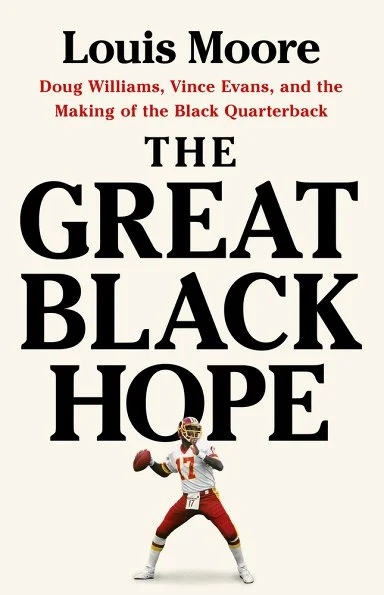

A lifetime later, I would learn from Prof. Louis Moore’s wonderful book, The Great Black Hope: Doug Williams, Vince Evans, and the Making of the Black Quarterback, that the reason Vince Evans was on the bench was because of a pervasive systemic bias against black quarterbacks in the NFL.

This bias has largely faded, but I swear the hangover of its legacy is what led the Bears to select big, white lummox Mitch Trubisky as the No. 2 pick in the 2017 draft while some guy named Patrick Mahomes slipped to No. 10.

I am now thinking about Heather McGhee’s The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Move Forward Together, and how a little less racism would’ve resulted in more Chicago Bears Super Bowl championships.

McGhee’s uses a framework of the “solidarity dividend” where the racists don’t need to give up on their racism as long as they recognize the ways that prejudice and inequality harm their own self-interest. We are in the midst of a literal government purge of Black, female, trans, and other minority groups because of their minority status. As I was typing this paragraph, I flipped over to BlueSky in a moment of distraction and saw the news that Trump had fired the first black officer to serve as the chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Only the most committed racists can see a benefit to firing someone from a job vital to our national security mere months into his multi-year term only to replace him with someone who needs a special waver because he lacks the qualifications for the job, and yet here we are.

—

I also recall a very early formative encounter with literary Black genius, the poet laureate of Illinois from 1968 until her death in the year 2000, and U.S. poet laureate in 1985-86. As memory serves, though I can’t absolutely confirm, Brooks pledged to attempt to visit every school in the state, and also established the Illinois Poetry Awards for students through every grade of K-12.

We read and wrote a lot of poetry in school because of Gwendolyn Brooks, and also maybe because writing poetry is a good way to learn to write when you are young and unfettered by the demands of making strict sense. I couldn’t say if Gwendolyn Brooks visited every school, but she did visit Greenbriar Grade School when I was a student there. In preparation, we each chose our best poems, and then grouped by class, taped them to the hallway walls. Ms. Brooks moved through the hallways making note of a line here or there.

She would’ve been the only Black face in the school, but it didn’t matter, not to me at least, nor I think most others, but who knows? I was a kid. We’d been told she was a celebrity, had been played recordings of her reading her work, including her most famous poem, “We Real Cool” which was short enough to memorize, but also we would never deliver it like Ms. Brooks.

We gathered in the auditorium for a reading. We listened, we applauded. We were told she was a great poet and we believed because what cause would we have to doubt it?

And also, it is obvious. By sheer coincidence this week, A.O. Scott of the New York Times has published an explication and appreciation of Gwendolyn Brooks’s sonnet, “my dreams, my works, must wait till after hell.”

Brooks often wrote of her Southside Chicago, Bronzeville neighborhood, a place a stone’s throw from where I grew up, and yet also a place totally foreign, except through experiences like the poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks.

I think I was lucky to grow up in a brief interregnum between the turmoil of the Civil Rights era and the racial revanchism kicked off by the Reagan Revolution now finding its full flower in Trumpism. It was no utopia, but there seemed to be general agreement that we should at least attempt to make progress. If anyone feared a few hundred white kids being ensorcelled by a Black woman poet in a grade school auditorium, those concerns did not reach my tender ears.

But today, I can’t help but observe that ultimately too much of white America could not handle Black excellence. I’m thinking about the 1619 Project, a deeply patriotic attempt to reconcile the treatment of Black people in America with the unfulfilled promise of American ideals and the way many have attempted to suppress progress. This attempt to simply tell a different story about the nation alongside what we’ve already heard could not be countenanced by many.

I’m thinking about how the percentage of Black faculty at our nation’s higher education institutions has barely budged in the last 30 years, and now appears to be trending down. Genuine diversity requires change, but even institutions purportedly committed to “DEI” could not figure out how to make room for Black excellence unless it came packaged like the white excellence already there. Many of these institutions are now giving up even the pretense of caring, perhaps grateful that Donald Trump has provided an excuse for their decades of failure to make good on their own promises.

How can we not be thinking of our first Black president who was 100% certified according to all the previous qualities of what stands for excellence and was still punished for the handful of occasions when he was judged too Black. (“Terrorist fist bump,” anyone?)

—

The high point of broad popularity for Sly Stone was perhaps “Everyday People.” In the film, Vernon Reid, best known as the guitarist of Living Color calls the Stone of that song, “the Black hippie pied piper, singing ‘we are the same whatever we do.’” Reid notes, “That’s the first time you hear that sentiment from a Black artist.”

The chorus, sung in unison sing-song by the full Family Stone conveys the message of a united humanity.

There is a blue one who can't accept The green one for living with A fat one tryin' to be a skinny one Different strokes for different folks And so on and so on and scooby-dooby-dooby We got to live together

Stone was beloved for, in Reid’s words, “the proof of concept” that we are all one people, but at “the same time, that message can be seen as problematic because they got their knee on my neck…they shootin’ brothers up.”

This is the bind of Black genius that Thompson wants to wrestle with through the lens of Sly Stone. To be wealthy, to be loved, you must appeal to the white majority, but the white majority is also hypersensitive and fragile. Stone follows up “Everyday People” with “Stand,” an anthem for the Black revolutionary liberation movement.

Stand In the end you'll still be you One that's done all the things you set out to do Stand There's a cross for you to bear Things to go through if you're going anywhere Stand For the things you know are right It's the truth that the truth makes them so uptight

The lyrics in “Stand” indict the white majority who can’t deal with the obvious injustice of segregation: “Its the truth that the truth makes them so uptight.”

Sly Stone’s peak as a Black artist was unprecedented, later to be followed by artists like Stevie Wonder, Prince, Michael Jackson, and now Beyonce. But Thompson shows us that the challenge of the Black genius to both reflect the lives of Black folks to Black folks and tp make the lives of Black folks acceptable to white folks is a nearly impossible bind.

We are not led to believe that it is this tension which led Sly Stone to the increasingly erratic life of an addict. There is also the money and fame and rock & roll. But Thompson notes with acute interest and historical footage of how Sly Stone was rather quickly written off as an inevitable tragic case, rather than continuing to be recognized as a genius with a problem.

Sly Stone’s contemporary, Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead, was surely more checked out on stage more times than any artist in history, but to his death from an overdose he remained the avuncular genius with a little heroin problem. Stone was treated like a degenerate. His genius could not protect him from his Blackness.

I am aware that I’m running the risk of painting Sly Lives as a work of tragedy, but this is not the effect of the film at all. It is joyous and real and human, and ends with Sly Stone sober, happy, safely removed from a world that could not accept his kind of genius and once again starting to receive his due.

We are in a very dark time. All of the noise about DEI and “merit” is a smokescreen for reality: The executive branch of the government is pursuing a program of resegregation and subjugation. It’s been more than 50 years since Sly Stone, and still we fear the Black genius.

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I paid tribute to Tom Robbins, one of the many writers who shaped my sensibility through an encounter when I was probably too young to be reading him.

At Inside Higher Ed I tried to put it as plainly as possible, Trump wants to destroy higher education. At

I had the distinct pleasure of doing a Q&A with my lawyer older brother about one of Trump’s mechanisms for destroying higher ed, his “Dear Colleague” letter that explicitly aims to destroy programs aimed at minority students.If you want to see me talk about More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI in person, I’ll be in San Francisco at Book Passage on Thursday, February 27th, and in the Chicago area at the Barrington White House Cultural Center on March 8th. I unlocked a career highlight by being reviewed in the Wall Street Journal by well-regarded grump Joseph Epstein, who both liked the book and was annoyed by my split infinitives.

is also a fan of the Sly Lives documentary and Sly and the Family Stone. I’ve been listening to them during the entirety of drafting this newsletter. Austin has recommendation for where to start with their music.Thanks to their investigation and the work of others to sound the alarm, 404 Media has gotten public library ebook service Hoopla to get rid of the AI slop that had been polluting their offerings.

Salman Rushdie’s attacker has been found guilty of attempted murder.

S.A. Cosby shared his six favorite books about serial killers.

A little AI-apocalypse humor via

and by Danniel Rodriguez: “Why I Chose to Reenter the Matrix and Be a Living Battery for the Machines.”Recommendations

1. The Wedding People by Alison Espach

2. Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks

3. Rosamond Lehmann in Vegas by Nick Hornby

4. Darius the Great Deserves Better by Adib Khorram

5. An Hour Before Daylight by Jimmy Carter

Michelle C. - Durham, NC

I think Flight by

will be a good fit for Michelle.It’s been a very gratifying week on the old reviews of More Than Words front. In addition to Joseph Epstein at the WSJ, David Perry covered it alongside Hacking College: Why the Major Doesn’t Matter —And What Really Does, a book that I enthusiastically blurbed.

If my work can be helpful to anyone who wants to figure out how to navigate the challenges of writing or teaching writing in the age of AI, you can get in touch with me by replying to this message or through my website.

Stay strong in these strange times, everyone,

John

The Biblioracle

Growing up in Augusta, GA, James Brown's hometown, shaped my understanding of the history of music.

Most people point to jazz and bluegrass, and lately, Hip Hop. Funk deserves to be added to the list of great musical forms that black genius at work on this continent has given the world.

I'm writing this from a cafe in New Orleans, home of The Meters, reading about a revival of interest in Sly Stone, who did his thing in California, while a Stevie Wonder song recorded in Detroit plays on the sound system.

Given the history of this place since people started crossing the Atlantic Ocean, "What is going on here?" is asking a similar question as "What is Black genius?"

John, thank you for the personal, pointed, timely article.