Where'd The Postmodernists Go?

A major strain of American literature seems to have faded away

My Chicago Tribune column this week is a brief recognition of the work of the writer John Barth, who passed away at age 93 on April 2nd.

Barth was a giant of American postmodern literature, publishing a number of significant novels including The Sot-Weed Factor, Giles Goat-Boy, and Chimera, which won a (shared) National Book Award for fiction in 1973.

Barth was also well-known for a kind of manifesto of postmodern literature, “The Literature of Exhaustion,” published in The Atlantic in 1967. The “exhaustion” Barth was referring to was the sense that more traditional forms of storytelling had been so thoroughly explored that writers were thirsty for different more expansive approaches. Barth’s lodestars were Samuel Beckett (who was also claimed by the modernists) and Jorge Luis Borges. I’m oversimplifying a bit here, but essentially, Barth was a believer in the potential of literature to interrogate the nature of storytelling itself, while also delivering a narrative.

Postmodern works are dense with allusions, and frequently contain metafictional elements that comment on the story being told in some way. It’s always a little arbitrary to put labels on writers and eras, but a good early touchstone is Borges’ short story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” - first published in Spanish in 1939 - that is, for me, the launching point for what would ultimately inform the 60’s and 70’s American postmodernists. In “Pierre Menard…” the text is a review by a critic of the attempts by the title character to literally recreate the entire text of Don Quixote, as though this makes a new original work. The conceit is a way to comment on issues of literary criticism and authorship through a fundamentally ironic lens.

Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962) which centers on a poem by one author that is then commented on by another with the narrative emerging through the combination of these texts is another instructive early example.

A series of surface-level (yet still useful) distinctions between modernism and postmodernism

The people who know more about this stuff that I do will cringe at the broad distinctions I’m about to make, but I never taught literature beyond the gen-ed, 200-level, so these distinctions are good enough to advance the conversation for the purposes of a newsletter focused on regular old readers, rather than academic discourse.)

Basically, your modernists, even highly experimental ones like Joyce, Faulkner, Or Virginia Woolf still believed that there was some essential “truth” to be discovered through the creation of the art object. The attempts at verisimilitude of the realists before them were just not up to the task, so the modernists thought you had to start to play around with perspective and language in order to really get at what’s up.

The easiest way to think about what distinguishes the postmodernists from their modernist forebears is to recognize the fundamental centrality of irony in the text. Where the modernists were convinced there was a truth to be rendered, the postmodernists are not so sure. In addition to Barth’s literature of exhaustion, I would add the “literature of suspicion,” and one of the things that the postmodernists who arose after WWII, having witnessed the atrocities of the Holocaust and the world destroying potential of atomic and then nuclear weaponry, suspected is that we were all thoroughly doomed.

There’s a lot of playing around in postmodern fiction, fracturing forms, interrogating genre. Pynchon, Vonnegut, and DeLillo all messed around with this stuff and became major writers in the process. This work was all decidedly mainstream in terms of “literary” fiction. Donald Barthelme published literally hundreds of times in The New Yorker in the 60’s and 70’s. Some of the stories in John Barth’s story collection Lost in the Funhouse (1968) first appeared in Esquire.

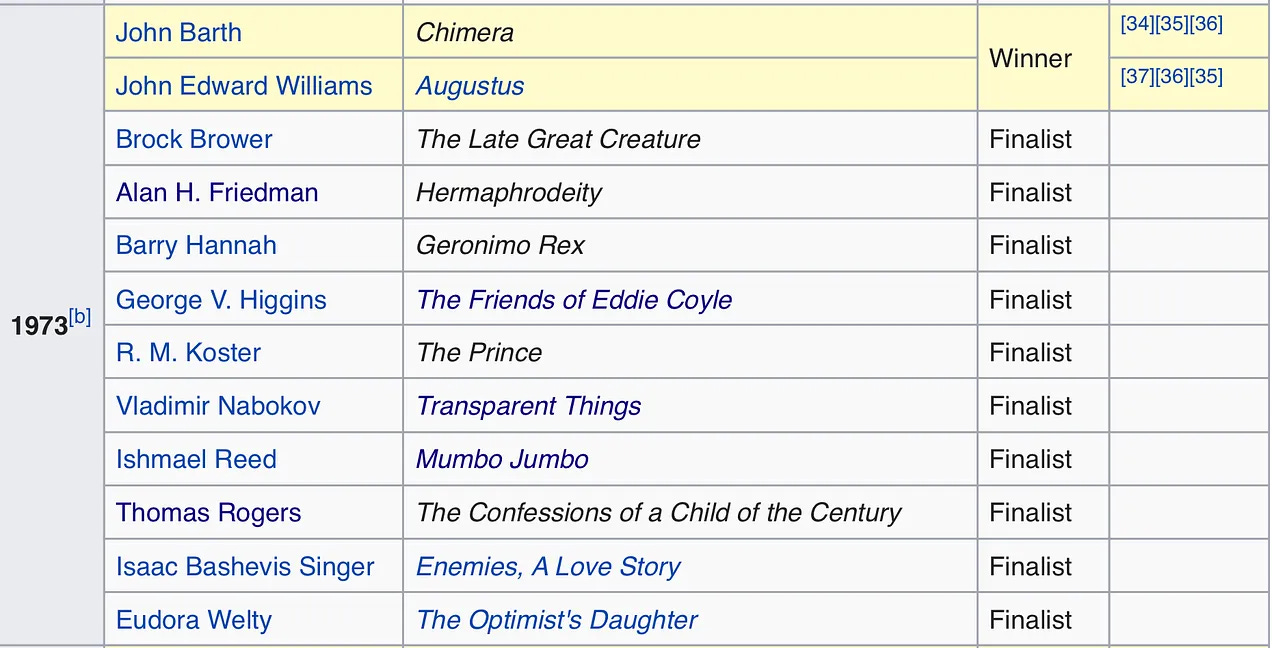

I wrote previously about how for three years (1973-1975), the National Book Award essentially split the award between a postmodern novel and one more rooted in realist or modernist traditions.

The 1973 finalists (the year Chimera split the award with John Williams’ Augustus) is an interesting mix of different approaches to novel making.

In addition to Chimera, The Late Great Creature, Hermaphrodeity, and Mumbo Jumbo are all recognizably postmodern. Nabokov too, but by this time he’d almost become his own category. The Prince, a magical realist novel, arguably qualifies too as a kind of sub genre under the larger postmodern umbrella.

All of the non-postmodern novels remain in print to this day. Of the postmodernists, Barth, Reed, and Nabokov’s books are still in print - all having achieved the status of major writer, and Mumbo Jumbo itself being a major book - but all of the others have largely faded.

Post 70’s postmodernists

Donald Antrim published three wonderful postmodern works in the 90’s (Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World, The Hundred Brothers, and The Verificationist), all of which were subsequently re-published in the 2010’s, but Antrim remains cultishly popular, primarily among Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine (1989) made a decent imprint on the public as have his other books, but in his later career he’s primarily become an essayist.

Infinite Jest (1996) is obviously indebted to the postmodernists. House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski, a puzzle of a novel that blends horror and metafictional conceits, was a surprise best seller in the year 2000. Marisha Pessl’s Special Topics in Calamity Physics also plays around with form in ways reminiscent of the earlier postmodernists, and made a big splash in 2006.

Garth Risk Hallberg received a reported $2 million advance for City on Fire (2015) a sprawling doorstop novel about New York City, which included “found” texts with the main narrative. The book is now primarily known for its failure to live up to the hype, though it’s a kind of awesome achievement. It just wasn’t something that ultimately huge numbers of readers were going to latch on to.

One possible exception to my observation is Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown, which incorporates a film script a metafictional conceit into his exploration of race and identity as his character, Willis Wu, tries to see himself as Kung Fu Guy, rather than Generic Asian Man, the role he’s been cast to play by the world around him. Yu utilizes the full back of metafictional tricks, story within a story, authorial commentary, you name it, and readers seemed to take to it quite well, so it’s not as though there’s something inherently off-putting about postmodern metafictional fooling around.

I used to read Donald Barthelme’s “The School” or “Some of Us Had Been Threatening Our Friend Colby” out loud to my intro fiction writing students and they loved them, but rarely if every did I have a student take a shot at writing a story like them.

Maybe it’s worth asking what’s happened, as well as what’s happening.

Why’d they go away?

I’m sure some of this is rooted simply in the fact that tastes and movements change over time. There’s never any reason to think that a particular trend in literature signals some kind of permanent shift in the form. Even when something “new” arrives like the post-war postmodernists you can find an antecedent. There isn’t a more crazy-ass novel that seems like a work of the postmodern period than The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Stern that was published serially starting in 1759.

Still, it seems like the artistic impulse to make these fictions and/or the market’s interest in publishing them has steadily waned. One theory I have is that creative writing inside higher education spaces and the workshop model that dominates is not well-suited to the production and discussion of this kind of literature. The workshop privileges the discussion of the “elements” of a short story like character, point-of-view, voice, etc…often weighed against a default (essentially) realist standard. The characters in Barthelme’s “The School” are not meant to represent some standard of observable reality. It’s the kind of piece that either resonates with you or it doesn’t and while there’s much to be said in terms of a critical analysis of its meaning and context through the lens of scholarship, it’s not the kind of thing you would want to spend a lot of time talking about in terms of those traditional conceptions of “craft.”

One of the criticisms of writers like Barth and Pynchon, that all this messing around was somehow obscuring, rather than revealing meaning. Pynchon was denied the Pulitzer Prize for Gravity’s Rainbow in 1974 because despite being recommended by the prize jury, the Pulitzer board declared the novel, “overwritten” and “unreadable.”

For all of the energy around the postmodernists, a good chunk of the public rejected it from the get-go.

Another factor is that the world changed underneath us. I’ve argued that the postmodernists were replaced by post-postmodernists that I call the “new sincerity” which employs irony, satire, and humor, but rather than it being a comment on life being a soul-sucking experience inevitably headed towards oblivion, these moves could be employed in the service of saying something sincere and inspiring about the potential for reifying our own humanity. My friend Dave Eggers is a transitional figure here with his memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius which utilizes a number of metafictional tricks in the opening section, but ultimately becomes a very sincere and moving plea for people to believe that humans can do good things if we stick together.

George Saunders is perhaps the best example of the new sincerity. I’m thinking of his story “Winky” first published in the New Yorker, and later collected in Pastoralia. The protagonist is Neil Yaniky, a sad sack who lives with his mentally challenged, but loving, sister, who heads off to a Tony Robbins-style self-empowerment seminar to try to find the courage to live a life of his own. Saunders paints the seminar in broadly comic tones, the reader recognizing the empty absurdity of the event even as Yaniky thinks he’s benefitting. Yaniky leaves the seminar determined to cast Winky, who he’s decided is his burden, out of his life, a choice we understand is ill-thought. I won’t spoil the ending, but it is considerably more hopeful than not when it comes to a statement on the human spirit.

Another theory, put forward by a guy named Alan Kirby, is that post-postmodernism is an era of “pseudomoderinsm,” in that digital culture and the internet now requires interaction between creator and audience for the text to take on meaning. Kirby, writing in 2006, is referring to things like reality television competitions which required audience interactions, or documentaries like Supersize Me, which are literal performances tracked over time, but this could easily apply to TikTokers or YouTubers. “Smash that like button” is the lingua franca of a pseudomodern age.

Kirby sees this as a kind of deliberate infantilization, where, having thrown up one’s hands in defeat thanks to the nihilism of the postmodernists, we gravitate towards the literally trivial as a form of comfort. Living with irony has become untenable so we replace irony with what Kirby calls “the trance,” which seems like a pretty good description of what happens when we scroll online.

This adopts the postmodern mindset that meaning and truth are unattainable, but rather than confronting this condition, we choose to benumb ourselves.

What’s Next?

Having worked through some of these thoughts regarding the recent past, I can’t help but consider what might be coming, what forces may shape how we look at narrative art in the coming years.

One big shift already here seems to be a large and perhaps increasing strain of thought that rejects the postmodern notion of the elusiveness of knowledge for an approach that suggests truth can indeed be corralled through sufficiently rigorous study. The so-called rationalist community as exemplified by writers like Scott Alexander (Slate Star Codex) or Julia Galef (The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don’t) clearly posits that there are correct answers to existential questions.

I think this is a dressed-up form of whistling past the graveyard. It may be preferable to Kirby’s pseudomodern turn towards and embrace of the trivial, but the idea that we could actually figure this stuff out if we just adopt the right mindset and gather enough data is a lot of fancy talk, soothing woo-woo in order to deal with the terror of the unknowable. This mentality applied to fictional narrative art would make for grim reading indeed as it seeks to banish ambiguity. The most prominent fictional text of this movement is Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, a Harry Potter fan fiction by Eliezer Yudkowsky, a book that I swear exists because I’ve seen it, and is so odd I would have thought it’s an extended put on except Yudkowsky’s other work around AI and rationality reveals that it is entirely sincere. (Yudkowsky believes it is a rock solid certainty that we will be exterminated by super intelligent AGI.) In the book, the orphan Harry is raised by his Aunt Petunia who married an Oxford professor that tutors Harry on rational thinking, rather than magic. Check it out for yourself if you want to see what that turns into, story-wise.

To this world-view we’ve now added generative AI, with a future of Artificial General Intelligence (supposedly) on the horizon, technology which not only contains all knowledge, but knows what to do with it. This is a crowd that believes that the impulse to write a book on a subject may be a mistake.

Convicted fraudster, Sam Bankman-Fried, himself part of the rationalist movement through his support of effective altruism told a journalist, “I'm very skeptical of books. I don't want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that... I think, if you wrote a book, you f—ed up, and it should have been a six-paragraph blog post.”

Elon Musk said something similar on Twitter recently. This is a mindset that thinks success is a matter of cutting to the chase and experience is overrated. To these people, all the dancing around a writer like Thomas Pynchon does over the 800 pages of Gravity’s Rainbow is a big waste of time, as is the act of reading it.

Obviously I think these people are self-deluding cuckoos, but their’s is a mentality that seems to hold considerable sway in our culture these days. Maris Kreizman calls this impulse the “bulletpointization” of books, the belief that we can reduce everything to easily digestible “content” and the more content we can consume, the better off we’ll be.

What this does to art and literature will likely be a subject for someone writing after I’m no longer around, presuming writing is still something people do by then.

In the meantime, I’m going to continue to focus my reading time on works the spring from the amazing variety of human minds we have in the world today.

Links

In other John Warner creates content news, at Inside Higher Ed this week I laid down some things in higher ed that I think should be off limits to AI, but apparently aren’t.

In even more exciting news, I’ve relaunched my education-related newsletter under a new name

and new sponsor, the social writing game, Frankenstories. If you’ve been interested in my perspective towards AI and writing here, you might consider subscribing, as I’ll be exploring how we deal with the problem of student engagement with school more broadly through original articles, interviews, and other fun stuff.The Whiting Awards for emerging authors have been announced. So have the finalists for the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction.

The list for the 2024 Guggenheim Fellows has also been announced causing some consternation among cultural creative types, a group with which I identify. I’ve never applied for a Goog because I know I don’t have a shot, so my resentment doesn’t extend from being looked over so much as pursuing the list of awardees and seeing people who work in the most well-resourced institutions in the country (like the Ivy League) and who have achieved professional success that surely carries material security with it. There’s no doubt that in addition to the $50k (or so), having been identified as a fellow has significant cultural cache, a kind of career award, and that’s cool, but it really is a program that delivers millions of dollars of fellowship money to people who don’t need it. It feels like a bad use of resources, but hey, those who amassed generational wealth through mining and smelting apparently get to use their money as they see fit.

From McSweeney’s this week: “You Can Try Sample Questions from the New SATs or You Can Hit Yourself Over the Head Repeatedly With This Plumber’s Wrench” by Dan Wilbur.

Recommendations

1. Transit of Venus by Shirley Hazzard

2. Once Upon a River by Diane Setterfield

3. Veritas: A Harvard Professor, A Con Man and the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife by Ariel Sabar

4. The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry

5. Kinder Than Solitude by Yiyun Li

Constance M. - Bethesda, MD

I’m going to ask for a mulligan if Constance has read this, but Matrix by Lauren Groff feels like the right pick here.

1. Three by Ann Quin

2. The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez

3. Heroines by Kate Zambreno

4. The Body in Question by Jill Ciment

5. The Door by Magda Szabo

M Feather - Seattle, WA

This is a great list for me to recommend a contemporary writer who is genuinely working in ways that seem very rooted in the postmodernist tradition and is making some headway with audiences and critics in doing it: Terrace Story by Hillary Leichter.

After long last, I’m pretty much caught up to recommendation requests, so barring a flood triggered by this message, wait times should be relatively short.1

As always, agreement, alternate theories, random thoughts and recommendations are welcome in the comments. And if you’ve read this far, let me suggest that you have perhaps enjoyed this newsletter and if you haven’t subscribed already, choosing to do so may be appropriate.

See you next week,

JW

The Biblioracle

All books (with the occasional exception) linked throughout the newsletter go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and an additional reading/writing/literacy nonprofit to be determined. Affiliate income for this year is $55.20.

Hi. I have a weird love of over-simplified "modernist vs. post-modernist" definitions that always do better than the deeper takes, and yours is pretty great.

I also love your take on rationalism pretty much as a method of sequestering the fear of the unknown, particularly death. This is especially important in the pseudo-Revelations structure of the post-human / singularity zealots of Silicon Valley. But the reason I like your take particularly is because intellectually I am really attracted to rationalism -- I really want things to be rational and understandable through logic whenever feasible -- but when I learned the rationalists existed I spent some time with their work and immediately realized that something profound was missing.

I had a very long streak in my teenage years involving a lot of death: friends, family, classmates. For about seven years I attended funerals all too frequently. And the midpoint of that period was 9/11. So one thing I learned during that period was that American culture's materialistic magical thinking that we call the Dream is exceptionally incapable of handling the discomfort of death. It's one of the areas where I believe Americans in particular are broken, even if the world overall is dealing with similar issues.

And rationalism obviously, in fact cringingly, is just another magnitude higher of desperately seeking to keep death out of sight. Which is really sad because another thing I learned about my seven years of death is that when you can look death in the face, in fact in the mirror, you really can own your own mind and its agency without any of the puzzles and games rationalists set up for themselves to keep their minds busy.

In that sense I love that you referred to Gravity's Rainbow particularly as the exact sort of book that would do those people a lot of good to read. I conclude the same often. These guys are clearly intelligent but too lost to get smart.

I bet Sam Bankman-Fried wishes he had a book right now.