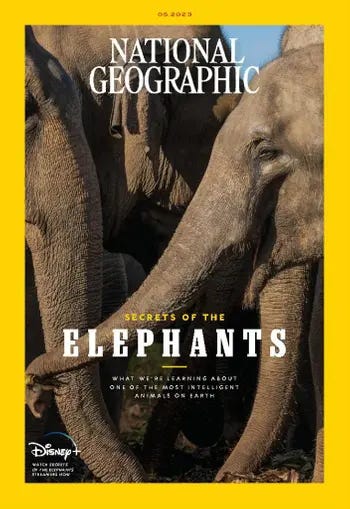

National Geographic has laid off all of its staff writers and a significant proportion of its editors, leaving behind a skeleton crew that will continue to produce the magazine with freelance contributions. The layoffs are part of a much bigger cost-cutting program by parent company Disney, which had acquired the property in 2017 as part of its purchase of 21st Century Fox, which had previously assumed majority ownership in 2015.

National Geographic has over a million subscribers and will continue to produce issues, but this is an obvious blow to a magazine that has been publishing in some form since 1888.

The news struck me because for the entirety of grade school, if I had to write or present some kind of report, I worked from two main sources, National Geographic and the World Book Encyclopedia.

When I say “worked from” I mean basically copied verbatim since the prevailing philosophies around plagiarism for grade schoolers was that no such thing existed. The purpose of these exercises was not to get us to produce passable academic(ish) writing, but to engender a bit of curiosity and independent information seeking and then report back to the group. I even still remember a handful of facts about some of this work, including the geologic processes that resulted in the development of Minnesota’s Iron Range, which prominently featured in my report on the state of Minnesota, creatively titled “Minnesota.”

Our National Geographic subscription was an annual Christmas gift from one of the grandmothers, and to my knowledge largely went unread until my brother or I would go scouring for information or inspiration. I seem to recall cutting many a picture out for the purposes of creating a collage for one reason or another.

It’s obviously bad news that a mega billion dollar corporation decides to operate a legacy print institution on the cheap. While I think the physical book is here to stay, it seems possible the print media will ultimately go extinct or nearly so.

When I get distressed about these things, I try to take a beat and check myself as to whether or not my distress is truly rooted in substance, or instead a kind of nostalgia for the world of the past that made sense to me, as opposed to this changeable, foreign space of the present.

It’s like when you see parents complaining online about some aspect of their child’s math homework that they don’t understand because their children are being taught to think with math, rather than simply grind through the mechanical operations of math as my generation did.

The new method is demonstrably better, proven as such by research and feedback from students who report being significantly more interested in math because of it.

(It’s ironic given that writing instruction has gone the other way, devolving to teaching students constrained mechanical operations in order to pass surface-level assessments, rather than allowing them to think, but that’s a topic for another day.)

What does it mean for the world where things like National Geographic and the World Book Encyclopedia are or perhaps soon will be, quite literally, dead?

Most of the time I don’t feel so very old, but when I started graduate school in 1994, I arrived in Lake Charles, LA with the following core tools for writing.

Toshiba laptop computer running Windows 3.1, where I didn’t actually need the Windows OS because I still used WordPerfect for DOS as my word processing program of choice, having been trained on it at my post-college job.

Merriam Webster Dictionary

Roget’s Thesaurus

The Macmillan Visual Dictionary

The visual dictionary is exactly what it sounds like, a book filled with illustrations of things you might want to have names for, like the major bones of the human body, or parts of a house.

If you wanted the term for the little flap at the trailing edge of an airplane wing that controls how the plane tilts left and right, you go to the jet plane page of the visual dictionary and learn it’s called an aileron. I believe the visual dictionary was a going away and starting grad school gift from my mom. I don’t know that I used it all that much while I was writing, but I looked at it all the time because the illustrations were cool and it was reassuring to know that all these things had names.

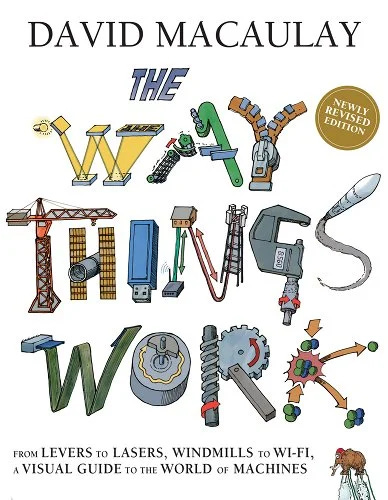

My interest in the visual dictionary was also reminiscent of my childhood interest in the books of David Macaulay, books like Cathedral, Castle, and Pyramid.

If you don’t know Macaulay’s work, it’s very worth tracking down copies of these classics, which combine his meticulous pen and ink drawings with descriptive narratives of how these structures were built, step by step.

Macaulay’s biggest selling book, The Way Things Work a book I’ve owned several times, but don’t seem to have a copy of anymore is apparently available in a new, updated edition, and I will be ordering one post haste. Every bit of information in the book will be available somewhere else easily accessible on the internet, but it will not have the clarity, elegance and beauty of Macaulay’s illustrations.

Like the World Book or the dictionary, I took Macaulay’s presentation as absolutely authoritative. Why would I think otherwise? My only access to information about the world beyond my senses was through these kinds of books and I had no reason not to trust them. My guess is that Macaulay’s work holds up just fine, but as we well know, the World Book Encyclopedia was filled with some super wrong stuff.

Part of it was the fact that it took a huge amount of resources and dispersed effort to produce an encyclopedia. It was updated, at best, every few years, and selectively so. Referencing an encyclopedia from 1988 that discusses the great global power of the Soviet Union in the present tense in 1992 will have you looking like an idiot, given the Soviet Union no longer existed by then.

And of course the entries in a printed encyclopedia are riddled with biases that are largely hidden from the reader and rife with inaccuracies that will persist until there is an updated edition.

National Geographic was infused with the spirit of white colonialism from its inception, a spirit which its readership would not have viewed as biased, but as correct. Non-white people from foreign lands were frequently portrayed as “savages” by the white adventurers producing material for the publication.

It wasn’t until 2017 that National Geographic publicly acknowledged aspects of its racist past.

What does it mean that I invested so much authority in these sources? What is our source of authority now?

I was teaching a first-year writing and communication course at Virginia Tech when Wikipedia first became prominent. As instructors, we were cautioned to tell students not to use the site as a source in their research because of its unreliability. In fact, I have PowerPoints from the era in which I warned students from even accessing it at all, lest they be misled. Better to stick with the library and the sources that have been approved and vetted by the authorities we trust.

But only a couple of years afterward, I found myself frequently using Wikipedia as a resource to get up to speed on a topic I might not know, and following the breadcrumbs of sources linked in the Wikipedia entry as a shortcut for my own research. If I wanted to know what the flap at the rear of an airplane wing was called, I wasn’t cracking out my visual dictionary anymore. If I wanted to explain the concept of semiotics to my students because the word had cropped up in one of our readings, and I only had a vague notion of its meaning, I went to Wikipedia.

Soon enough, teaching students to use Wikipedia productively as part of their research processes became an explicit part of the course. Over time, that teaching became less and less necessary, as students arrived in my college course already well-versed in its use and its limitations.

They knew not to treat a Wikipedia entry as an infallible authority (though they often did so anyway), and over time, the research students conducted for the writing in my course moved further and further away from the library and on to the internet as the web became more and more populated with actual reliable information. I still required students to interact with academic databases and academic journals, but at times this felt almost archaic. I wanted them to know these things existed and what the difference was between something you dredged up from a Google search and something published via a process of peer review, but the vast majority of them were never going to intersect with peer reviewed research after college ever again.

I wanted them to know that the work they were reading in those journals was the product of a careful, multi-stage process, that it could therefore be trusted, that it was authoritative.

I don’t think I was foolish necessarily to believe this, or committing instructional malpractice in conveying it to my students, but we know this is not necessarily true. All the biases that infuse the old World Book Encyclopedia are present in academic literature too. We are also still in the midst of an almost two-decade '“replication crisis” in the sciences where huge swaths of once sacrosanct findings, particularly in the behavioral sciences cannot be reliably reproduced.

Perhaps you recall the famous Stanford Marshmallow Test where it was reported that a four-year-old’s ability to resist eating a treat being offered by a researcher was predictive of future success. This begat decades of educational practices around trying to explicitly teach children self-control and delayed gratification as though they are ultimately the keys to a prosperous future. As it turns out, the Marshmallow Test does not replicate and the original findings were skewed by an unrepresentative sample of children. While the observations of how different children respond to the challenge is of interest when it comes to understanding childhood behavior, the test has no predictive power for future outcomes.

For good reasons, the very notion of authority starts to look like a void, and into that void steps anti-vax cranks like Robert F. Kennedy Jr., or worse like followers of Qanon who have looked to nonsense oracular pronouncements as their authority. Donald Trump’s favorite phrase to his supporters is “believe me,” and many do, even though his lies are bottomless and transparent.

These movements are hugely dangerous, but we can’t be to surprised about their power and persistence given the difficulty of identifying truly reliable authorities.

And now we have Large Language Models like ChatGPT which will answer any question with apparent great confidence whether what it is sharing is accurate or not.

It’s enough to throw your hands up in despair and give up on believing anything is accurate or true, but to admit defeat is to succumb to chaos, and I’m not quite ready to do that yet.

The only way out is to go through and perhaps admit that there is no out, that making sense of the world is a never-ending process where we rinse and repeat what we think we know against what we encounter in the world on a daily basis.

If you can embrace curiosity and not become overly fixed in a position, it can actually be a pretty interesting way to live.

Links

My Chicago Tribune column this week is a reflection on Sarah Viren’s new memoir, To Name the Bigger Lie, a book which explores similar issues of authority rooted in our own inherently trustworthy memories of our lived experiences.

Also at the Tribune Christopher Borrelli reports from the American Library Association meeting and how librarians are fighting back against book bans.

Seeking to capitalize on the BookTok trend, TikTok parent company ByteDance is getting into book publishing. Will it work? I have no earthly idea.

At Esquire, Kate Dwyer writes about the new trend of publishing novella length novels, calling it the “Year of the Slim Volume.” At his newsletter

offers some additional perspective. I’m all for it. Give me a book I can start and finish on a two hour plane trip and I’m in heaven.Powell’s has released the books they’re anticipating in the third quarter of 2023. Meanwhile, the Chicago Review of Books has released their preview of Chicago books for the second half of the year, including Kathleen Rooney’s From Dust to Stardust, which Mrs. Biblioracle is presently enjoying.

The 75th anniversary of Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery recently passed and a number of writers comment on the story, its influence and lasting power. My original plan for the newsletter this week was to write about how I used to read that story out loud to my students as a way to demonstrate the emotional power of storytelling, but eventually, they’d all read it before reaching my class because the story was so heavily anthologized, so I switched to other stuff. Maybe I’ll get to it someday. I’d love to do two pieces a week sometimes here, but the time…the time…

This week’s literary themed piece from my friends at McSweeney’s: “The Very Hungry Caterpillar or Me at a Hotel Buffet” by Lisa Cowan.

Recommendations

All books linked here go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookstore at Bookshop.org. Affiliate proceeds, plus a personal matching donation of my own, go to Chicago’s Open Books and the Teacher Salary Project, which is advocating to establish a federal minimum salary for teachers of $60,000 per year. Affiliate income is $132.90 for the year.

1. Yellowface by RF Kuang

2. Men Without Women by Haruki Murakami

3. Writing Down The Bones: Freeing The Writer Within by Natalie Goldberg

4. Insurrecto by Gina Apostol

5. Packing My Library by Alberto Manguel

Bianca A. - Elche, Spain

In honor of the year of the slim volume, I’m recommending a slim volume, Things Like These by Claire Keegan.

So, tell me, what do you trust? Who do you trust? How do you work through the turbulence when you realize something you believed might not actually be true? Share your wisdom in the comments for the benefit of all.

I hope the American readers of this newsletter enjoy our national holiday and all sympathies to those of you with dogs who either cower or howl (or do both) at the sound of fireworks.

See you next week,

JW

The Biblioracle

I agree about The Lottery. This story should be taught in every school every year.

Thanks for this post, which brought back my own unquestioned childhood sources of info (as well as the very sad news about NatGeo). It also reminded me of the 80s bumper sticker, telling us to "Question Authority." I guess our current uncertainty is where that leads, but I really appreciate your positive conclusion: "If you can embrace curiosity and not become overly fixed in a position, it can actually be a pretty interesting way to live."