When the National Book Award Couldn't Decide

For three years, the award for fiction was split. I do some wondering why.

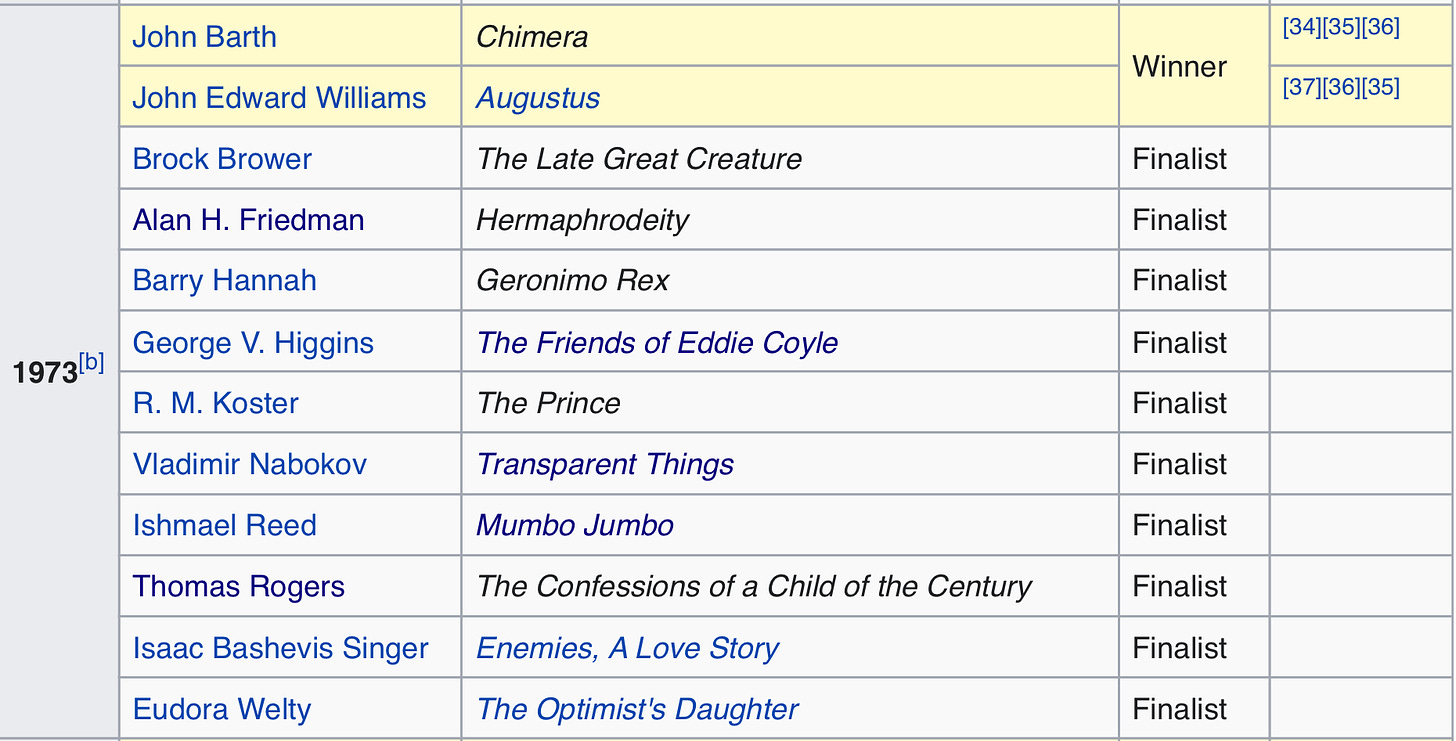

For three consecutive years, 1973-1975, the National Book Award for fiction was split between two books.

1973: Chimera by John Barth and Augustus by John Williams

1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon and A Crown of Feathers and Other Stories by Isaac Bashevis Singer

1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone and The Hair of Harold Roux by Thomas Williams.1

This was not done before, and hasn’t been done since.

I find that interesting.

My initial interest in the 1973 list was spurred by my “discovery” of The Confession of a Child of the Century by Thomas Rogers, a terrific book which has been almost totally forgotten, which I wrote about previously.

But then I got curious about this period where the juries for a major book award could not come to a consensus, and instead split the award, so consider this an extended think about that curiosity.

John Barth and John Williams were awarded the 1973 prize for two very different books, Chimera and Augustus. Williams today is more known for Stoner, and I don’t know how widely read Barth is anymore, but if you take a postmodern literature course, you’ll be introduced to him as one of the most important figures of his time.

I’m not smart or studied enough to give you any kind of authoritative lecture on the particulars in terms of how scholars view the various intersecting threads of the period, but looking at the list of finalists and the split award during that 1973-1975 span, it’s easy to detect a schism in American literature between those who were operating in an essentially realist mode, attempting to render the world in a recognizably straightforward way (Williams), and those who were determined to mess with the very fabric of storytelling (Barth).

It was a period when the avant-garde briefly broke through to mainstream.

I remember reading Barth’s collection Lost in the Funhouse in college and being some combination of bewildered and thrilled. At the time, I was much more in the thrall of “minimalist” writers like Raymond Carver and Ann Beattie who spun out tales of quiet, recognizable, domestic turbulence. While the particulars of how to achieve what Carver, Beattie, et al…were capable of obviously escaped me, I could at least understand both the map and territory of what they were up to. This is one of the reasons why so many young writers of my era were busy trying to write their own versions of these stories.

Barth, on the other hand, was interrogating myth, creating stories filled with allusions (and illusions) that I knew I was not grasping - an intuition confirmed by our class discussions - but which nonetheless roiled my spirit. I both resented that I wasn’t smart enough or well-read enough to “get” what Barth was up to, and admired the underlying impulse to play around with stories in this way.

Later on, after I’d read more of the experimental postmodernists of the time, particularly Donald Barthelme, I realized that the point wasn’t necessarily to parse every last reference and put together the pieces of a puzzle that had been scattered throughout the narrative, but to recognize that Barth and Carver were up to the same thing, leaping from some nugget of the human condition and seeing where their imaginations might take them.

Stories don’t have to be figured out to be enjoyed; they just have to be experienced. Once I recognized it was absolutely okay to not “get” every last reference or allusion that could be unearthed from a text, and it’s just fine to simply run with whatever pleasure a text may give you,2 I found myself besotted by the postmodernists, radically altering my personal approach to writing short fiction, moving from Carver imitations to Barthelme imitations, as in this piece, "Notes from a Neighborhood War."

The big advantage many of these postmodernists had over the minimalist/realist strain, and a trait that strongly attracted me, was that they were often very very funny.

For example, I have read Donald Barthelme’s short story “The School” out loud to hundreds of students and if any of them were not LOL’ing at some point, I can’t recall it.

Raymond Carver may be able to deliver a soul shattering epiphany, but he’s not going to give you a case of the giggles.

You can see the competing strains, and even a couple of other variants across the full list of 1973 finalists. Welty (The Optimtist’s Daughter) and Singer (Enemies, a Love Story) are essentially realist. So too is The Friends of Eddie Coyle, a classic crime novel that was groundbreaking in its unromantic treatment of organized crime, a contrast to Mario Puzo’s more operatic The Godfather.

Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo, and R.M. Koster’s The Prince are more experimental, with elements of magical realism. Reed’s work is as wild and intertextual as anyone, and I was about to call him the Afrocentric Pynchon until I realized that Pynchon is more like a Eurocentric Ishmael Reed.

After those years of splitting the National Book Award prize, the experimental/unconventional strain of American literature stood alone at the top in 1976 in the form of William Gaddis’ J R, an 800-page novel about an eleven-year-old stock trading genius told almost entirely in dialog. It is a challenging read, and a brilliant, satirical indictment of American greed, a Catch-22 of finance. I would say it’s one of my favorite books, or at least one I most enjoyed reading as I was reading it, but I almost never recommend it because I know that vast majority of readers will not connect with the style and the story.

J R’s win was both the peak and end of highly experimental literature of its kind being honored with a National Book Award. Occasional unconventional texts pop up here and there (including Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown in 2020), but they are the exception, rather than the rule.

This is observation, not judgement. The prizewinning books since 1976 are larded with titles I love (truly too many to list).

But at the same time, that spirit of experimentation, and particularly the biting satirical strain of the postmodernists of that period, is largely gone from the list of NBA-winning and nominated books by the 1980s.

There are occasional exceptions, for example, the 2006 nomination of Mark Z. Danielewski’s Only Revolutions, his follow-up to the even more adventurous, House of Leaves, Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo show up as nominees, having apparently been grandfathered in during previous periods.

But these are the exceptions that prove the rule, that the brief flare of experimental acceptance into the mainstream had passed.

We’re I a real book critic, I could give you a more grounded theory as to why this is the case, but I think there’s a couple of factors at work. One is that the books of the experimental postmodernists are much less accessible to the general reader. This is an observation, not a judgement, but as I experienced back with my first encounters with these writers in college, by design these books are designed to disorient the reader, in order to make them consider stories and storytelling anew.

For a novel like J R, it can be frequently hard to even parse what you are reading. The story unfolds through inference as the novel trains you to read it. When you connect with a book like this, the reading experience is amazing, unparalleled even. When I read Mumbo Jumbo years ago, I knew that vast swaths of the book were flying past me, and yet the wicked energy of the book was more than enough to keep me reading, and then make me seek out more of Reed’s work.

There was a period where this kind of work was supported by the commercial mainstream - not readers necessarily making these books bestsellers - but the people in charge of shaping American literature through the running of institutions. Donald Barthelme published more than 80 of his short stories in the New Yorker, many of them bizarre and surreal and wonderful, like one of my favorites “Some of Us Had Been Threatening Our Friend Colby,” a masterpiece of dark, deadpan humor.

Over time, this sort of material has retreated closer to the margins, preserved at places like McSweeney’s, but carrying considerably less cultural weight.

Another factor may simply be the evolution and impact of the intersection of media and culture, a point that David Foster Wallace made in this interview from 1996, when he appeared on a panel with Mark Leyner (My Cousin, My Gastroenterologist) and Jonathan Franzen, who at the time had only published Strong Motion, his first novel.

Foster Wallace calls television his “main artistic snorkel to the universe,” and argues that television requires “very little” work on behalf of the recipient, and that orientation has made audiences less interested in media (like challenging books) that may ask more of them. Foster Wallace managed to thread this needle with his famously challenging Infinite Jest, but it’s important to remember that it was the novelty of people reading the book that consisted of a big part of the phenomenon, and in comparative terms, Colleen Hoover sells more books in a week than David Foster Wallace did in the full span of his career.

David Foster Wallace’s fellow panelist and close friend, Jonathan Franzen, tackled the phenomenon of hard to read books in his famous essay, “Mr. Difficult,” (2002) in which he discusses the state of contemporary novel writing through the lens of primarily wrestling with the work of William Gaddis. When dedicating six to eight hours a day to the project, Franzen finished Gaddis’s The Recognitions (a title which influenced Franzen’s own breakthrough novel The Corrections), but years later is defeated by J R, when he cannot spend more than an hour or two a day with the book.

Franzen delineates the difference between the “status” novel, which is essentially a work aspiring to high art, written without concern for the audience reaction, and the “contract” novel, which is designed with the engagement and pleasure of the audience in mind. This is not necessarily a mass versus niche audience divide. Very niche books can nonetheless by contract novels, provided they are catering to that niche.

Franzen was widely criticized for what some took to be his dismissal of status novels, but to my mind, this was always a misreading. Franzen identifies strongly with those authors (Gaddis, DeLillo, Pynchon), and really, wanted to become one of them, but having failed to achieve recognition with his first two books, he turned to a more contract-oriented approach in The Corrections. It’s not a judgment so much as a lament, for himself, and for the world.

In the full cut of that panel discussion, Mark Leyner starts things off by essentially saying he doesn’t give any thought to his audience as he writes. If you’ve read any of Leyner’s work, you can tell that he’s serious. He continues to write challenging, experimental books reflective of a singular intelligence.

But unlike Franzen, whose every book is now a guaranteed best seller, Leyner continues to be published by mainstream commercial publishers, but is not widely read. He continues to challenge readers, apparently even changing the same of his latest novel between the hardcover and paperback releases from Last Orgy of the Divine Hermit to Daughter (Waiting for her Drunk Father to Return from the Men’s Room).

By definition, the avant-garde cannot be mainstream, so those years of the shared awards should properly be seen an anomalous, though in the same interview cited above, I think Foster Wallace captures something that perhaps did go missing, referring to the avant-garde work of the time (late 90’s, early 2000’s) as “hellaciously unfun” as compared to the late 60’s/early 70’s postmodernists he so loved and was influenced by, labeling the avant-garde of his time “academic” and “cloistered.”

Ironically, using Franzen’s taxonomy from “Mr. Difficult,” it is not the status novel nature of the avant-garde that doomed it to marginal status, but rather its evolution into a contract novel aimed at primarily academic audiences.

I think Franzen and Foster Wallace are (partially) on to something, but it’s going to take at least one more newsletter to tease it out.

I don’t know if a cliffhanger ending is part of the contract for Substack newsletter readers, but that’s what you’re getting this week, my friends.

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune, I round up six of my favorite reads from the fall that I just don’t have the time or space to review at the length they deserve, including Percival Everett’s Dr. No and Lynn Steger Strong’s Flight.

Do you want to be able to look at every list of best books of the year, aggregated all in one place? Then David Gutowski’s Largehearted Boy blog’s list of best of lists is for you.

Over at his newsletter, Paul Bowers has his "2022 Weirdy Specific Holiday Book Guide." At his

newsletter, Lincoln Michel tells us about three books we might have missed, and another to look out for in 2023.NPR’s massive “Books We Love” list of curated reads, sortable by category has been released.

The deal for Penguin Random House to purchase Simon & Schuster, previously blocked by a federal judge is now officially off.

As always, every book linked here goes to Bookshop.org, which has free shipping through the holiday weekend.

Recommendations

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $319.60 for the year.

1. The Idiot by Elif Batuman

2. My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante

3. Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin

4. The Woman Destroyed by Simone de Beauvoir

5. Normal People by Sally Rooney

Leila V. - Brussels, Belgium

Wonderful list of books, which ups the ante in terms of my recommendation because I think this is a high bar. I’m hoping Leila is okay wit short stories because I just feel like James Salter’s Dusk (and other Stories) is the absolute right call for her.

Announcing: Biblioracle Book Gift Giving Service

Next week’s column is my general guide to giving holiday gifts, so in honor of that, I thought I’d try an experiment where I open things up for folks to ask me to recommend a book they can give as a gift to someone else. If you’d like to use this service, either reply in the comments or send me an email (biblioracle@substack.com) with the following information.

Who the gift is for.

Relevant background about this person (age/interests/etc.)

What sorts of books (if any) that they currently read.

If there’s enough interest, I’ll include my recommendations in a future column. If there’s too much interest, I might not be able to reply to everyone, but I’ll do my best.

Until next time,

John

The Biblioracle

It’s worth noting that the Wikipedia entry for the NBF fiction award has the shared winners listed incorrectly for 1974 and 1975. The website for the National Book Foundation has the correct winners for every prize for every year.

I think this is good advice for reading literature in general, be it Shakespeare or Ulysses or Tristram Shandy or Don DeLillo, or Colleen Hoover. It doesn’t mean you abandon your critical faculties or judgment, but that you remain sufficiently open to what a text may have to give and not worry too much about judging yourself for what you may not be getting.

Without wanting to be a huge jerk about it (though unavoidably a minor jerk), I would note first that one *can* edit inaccurate Wikipedia entries and second that what fascinates me both about this post is that I believe Ann Beattie is the only woman mentioned in it. That's neither here nor there, and as a newcomer to this newsletter, I don't know that it signifies anything other than what a particular set of book critic people were thinking about in the last few decades of the 20th century.

I'll also spare you a recap of the argument I had with my mother the other day about the phrase "guilty pleasure," the purpose of reading, the purpose of existence, Aristotle, my dad, various works by CS Lewis, Lois McMaster Bujold, H. Rider Haggard, and some other things I've forgotten.