The Tournament of Books and the Ideal Book Review

There's a long history of excellent book conversation at the Tournament of Books

This is the time of year when

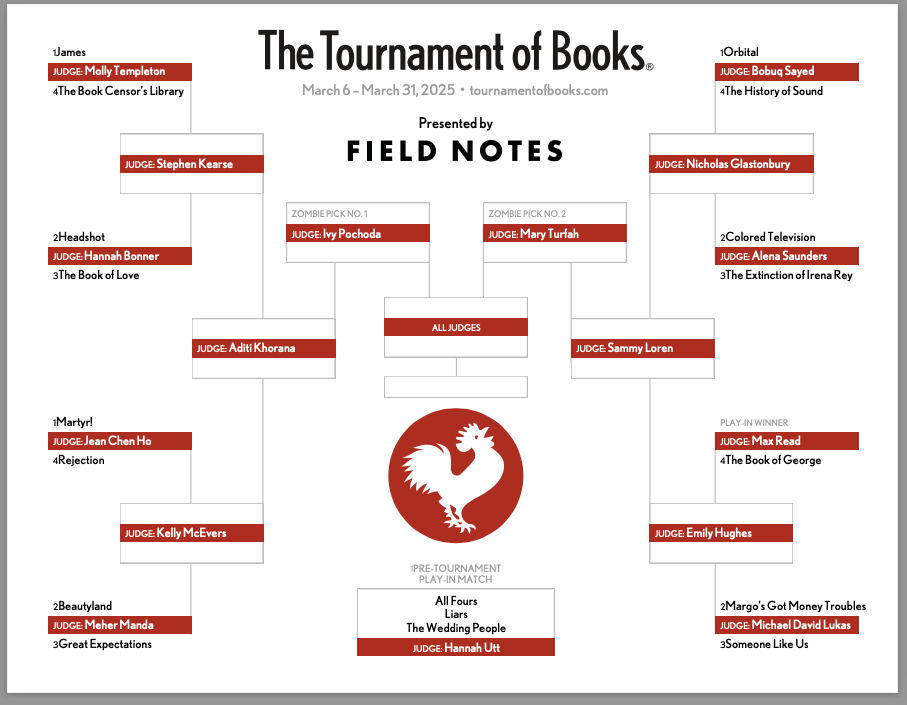

and I are in the midst of writing our share of color commentaries for the annual Tournament of Books and this has me thinking about what I, personally, like and need as reader from a book review.For those not familiar with the Tournament of Books - about to commence its 21st year on March 6th - it is a March Madness style competition for books where 16 books (following a three-book play-in round) compete for supremacy with one judge reading a pair of books and choosing a winner, while sharing the reasoning behind their judgement. You can see this year’s bracket just above this paragraph.

There is a whole history of the tournament, but it essentially started as a joke on book awards to illustrate the randomness and subjectivity of these things hidden underneath the aura of authority. The ToB puts all of that subjectivity on display while inviting the audience to comment as the tournament unfolds. Kevin and I are two of the color commentators who come in after the judge has rendered their verdict to offer additional thoughts and insights into that day’s competition. For years we were responsible for all of the color commentaries, but for the last few years we have been blessedly splitting those duties with Meave Gallagher and Alana Mohamed.

Longtime readers may recall that “the Biblioracle” was birthed in a desperate moment of ToB commentary where Kevin and I had run out of things to say, and on a whim I told readers that I would tell them what to read next if they listed the last five books they’d read. At the time, we would get maybe 20-25 total reader comments on a matchup, so I figured it wouldn’t be all that taxing, but we got hundreds of requests, lurkers coming out of the digital woodwork, and I spent basically eight straight hours recommending books.

At some point, I told myself that I was just going to get to everyone no matter what. It felt very John Henry vs. the steam engine where I was going to do something amazing, but maybe also I was going to keel over at the end.

I lived, and after that we did a couple of Biblioracle Live events, shortening the window for comments each time, until even with only 30 minutes, I still had over 100 requests. Not long after that last live session Kevin pitched me as a columnist for a new books section for the Chicago Tribune (Printers Row), and I’ve been writing weekly for the paper ever since, continuing even as Printers Row ceased to exist.

This is one of the stories I tell when young people come to me and ask about how to make a career as a writer, though even I don’t know what conclusions to draw from it other than have friends, try stuff, see what other people respond to, rinse and repeat ad infinitum.

Right…the judgements. I obviously can’t share any of this year’s judgements, but I’ve been reflecting on how fun it is to read these missives and consider the perspectives of the judges measured against my own experience of reading these books. My pleasure is not predicated on my involvement in the exercise via commentary. I read the matchups that Meave and Alana are responsible for with every bit as much interest, and of course the audience for the tournament exist primarily as spectators or discussants well after the fact in the comments.

So, what makes it so fun and interesting, and also for me, generative, in the sense that reading these judgements often cause me to have thoughts and feelings of my own, that I can then quite readily express in the commentaries?

At the heart is the DNA of the ToB as a vehicle for book conversations. It starts with the pairing, putting two books in juxtaposition to each other, a route towards putting them in conversation. We then have the judge’s response to this juxtaposition, a recounting of the internal conversation that the reader experienced. After that we have the color commentary, and after that the reader comments (which we’ve named “the commentariat.” Some days, there’s so much flying around commentariat, I can’t keep track of all the different threads. You never know what someone is going to pick up on. Could be their own feelings about the books. It could be something from the judge’s rendering or the color commentary. Comments beget more comments until sometimes there’s multiple hundreds of missives.

But it all starts with the judgements, which are overwhelmingly carefully crafted and then edited with close feedback from ToB co-founder Rosecrans Baldwin. Sometimes these things sound breezy, even tossed off because they read so naturally, but this is, of course, an illusion after the fact.

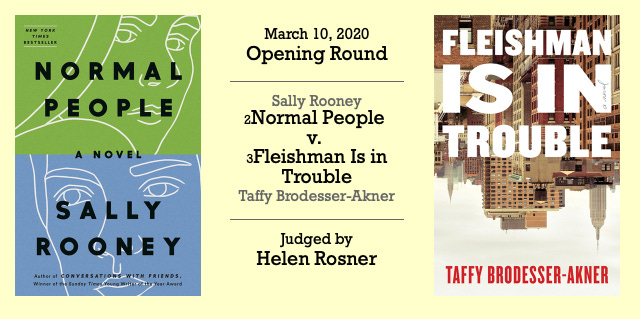

There’s a few patterns that have emerged over the years that I find interesting and I think are good for considering how to drive a critical conversation about a book. There are dozens of examples of these from the ToB history, but I’ve chosen one from an opening round matchup in the 2020 tournament.

To begin: Context and Positioning

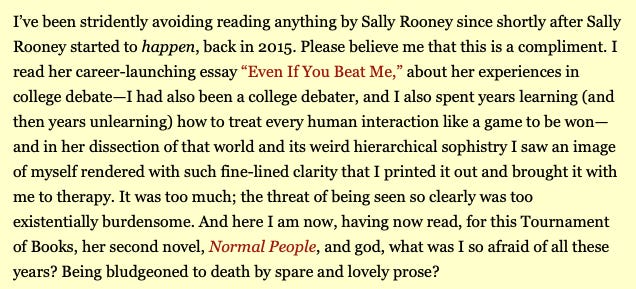

New Yorker staff writer Rosner starts her judgement the way many judges do, by first sharing what I call her “positioning” relative to the books and subject at hand.

Essentially, positioning answers an unstated, but important audience question: Where are you coming from on this particular deal? The context is useful because we’re heading towards a judgement, a determination, and this kind of background may be relevant to how the audience ultimately takes in the writer’s communication.

Sometimes in working with students I’ll substitute “baggage” for positioning, but same thing. What is it that you, specifically, bring to this experience that may be relevant to the judgement we’re about to read?

Additionally, we see the judge’s internal process at work. Positioning makes the internal thought process both transparent to the audience and visible to the writer themselves. This is very important and useful stuff.

Next: Summary and Response/Analysis

Rosner’s next move (that I won’t screenshot in the interests of space, but you can see if you click through to judgement) is to give us a brief summary of Normal People before segueing to her response to the text and some analysis of that response in the context of the novel.

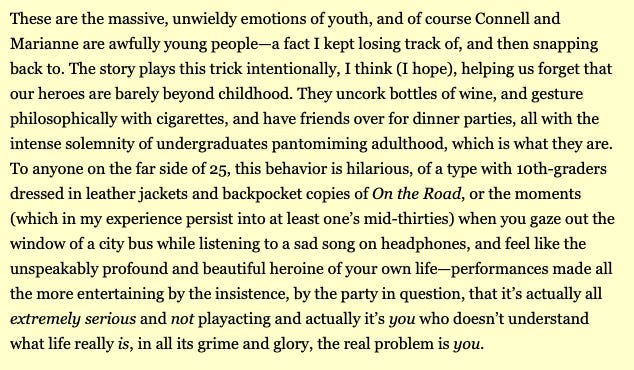

What we see here is a kind of analytical call-and-response that shows the work of critic in relationship to the audience. Rosner demonstrates her own understanding of what she perceives as the intentions and method deployed in Normal People (something all reviews should do, IMO), and then jumps from that understanding to a personal, but still analytical response. She’s mining her experience and understanding for insights that may illuminate the novel for the benefit of the reading audience.

The turn: What This Adds Up To

The next move is to go deeper into the critical response and draw some bigger conclusions. Rosner wrestles with her judgement of Normal People on the page:

The novel’s early sections so precisely evoke that euphoric disorientation of being fumblingly young and lost in infatuation that I, not young, felt a sort of breathless, aching grief at the realization that I will probably never have that again. The book is, in many ways, about sex, about what it means to love a person, what it means to make love to a body, and where those acts of love overlap and where they fail to meet. This is good stuff! This is what we’re here for! Let’s dig in and feel those feelings, narrated with gestural dispassion in close third!

But even after making this discovery, she questions it:

But this is also where the book lost me—where it abandoned me, really, I felt almost betrayed—as the ballad of Connell and Marianne enters its third act, and the sex becomes a clunky and violent metaphor, and the underlying farce is replaced by an oddly retrograde, overly pat morality play. Maybe the gravitas wasn’t a sly miracle, maybe it’s not actually a book about playing grown-up, maybe this story really is just an earnest telling of the most important years in its characters’ lives. How sad for them, if they are.

Next, Rosner goes through a nearly identical pattern for Fleishman Is in Trouble, zeroing in specifically on the narrative twist that what appears at first to be a standard third-person rendering of the life of a frustrated white man (in the tradition of the WMFUN), is actually being related by Libby, a friend of Fleishman’s with her own life and story.

Conclusion: Rendering a Verdict

In the context of the Tournament of Books, the verdict is literal, a choice between two competitors, but even in a more traditional, single-book review, I like a clear sense of the critic’s judgement. The audience is thinking: Is this book worth my time (or anyone’s time)? Why? What are its most interesting features or contributions to the larger literary conversation?

Rosner chose Fleishman Is in Trouble, though because of one of the quirks of the ToB, the Zombie Round (in which two eliminated books are returned to the action based on a pre-tournament reader poll), Normal People ended up as the 2020 champion.

The verdict of a regular review is not as definitive as an exercise where someone must choose between two books and name one the victor, but by the end, a good review makes it clear to the reader where the reviewer stands, even when that stance may be infused with some uncertainty or ambiguity.

Coda: Future Food for Thought

Another common feature in ToB judgements is an extension of the conclusion, a move that I framed for students as “food for thought,” something not necessarily specifically tied to these books, but a more general statement or speculation about books/literature/reading/art/whatever in general. The audience question this answer is: What does this all mean? Rosner does it this way:

What are novels like these, anyway? Characters live their lives, they fight their feelings and give into them, they screw and cry and walk around within the rooms of their tiny world, and the rest of humanity goes about their own small lives just off the page. It’s a finesse game, a metanarrative: It’s all in how you tell it, and the ways you pay attention to how it’s told.

Obviously, there’s no one way to structure a review, but by considering the audience’s needs at every step along the way, you can come up with something pretty satisfactory or better most of the time. I think Rosner’s judgement in this matchup was terrific (and said so at the time), but its terrific-ness is not rare during a typical Tournament of Books.

I know I have newsletter readers who are ToB fans, they can tell you. If you haven’t heard of the Tournament of Books before, there’s still time to do some reading of the short-list competitors, and 20 years of past tournaments to peruse.

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I discussed a new biography legendary television producer/writer Norman Lear.

At Inside Higher Ed, I explored the grief I think a lot of folks working in higher education might be feeling as they experience attempts to destroy that which they’ve dedicated their lives and careers to. At

I interviewed Center for the Defense of Academic Freedom fellow, Demetri Morgan, about a new work of public advisory for higher ed institution governing boards to resist external attacks on their missions.At LitHub I participated in “5 Authors, 7 Questions, No Wrong Answers.” Find out what I’d be doing if I wasn’t writing.

I thought this was a terrifically interesting profile of Na Kim, an artist and book designer of some very well-known covers.

I have a chapter in More Than Words titled “On the Future of Writing for Money” and this newsletter from

is a great illustration of why this future is so fraught.Never forget that I own Philip Roth’s old clock radio.

From my friends at

, “Government Welfare is Evil, Unless the Money Goes to the Wealthiest Man in the World” by Devorah Blachor.Recommendations

1. The Verneys, A True Story of Love, War, and Madness in Seventeenth-Century England, by Adrian Tinniswood

2. In Search of Amrit Kaur: A Lost Princess and Her Vanished World, by Livia Manera Sambuy, translated by Todd Portnowitz

3. They Came to Baghdad by Agatha Christie

4. A Dominant Character: The Radical Science and Restless Politics of J.B.S. Haldane, by Samanth Subramanian

5. Elements of Taste: Understanding What We Like and Why by Benjamin Errett

Ann M. - Seattle, WA

This is tough list for me. Not a lot of fiction, mostly very specific nonfiction that doesn’t necessarily line up around a particular focus. I’m going to take a stab with something that feels a little out of left field, but has always been a good choice for the fundamentally curious, Ways of Seeing by John Berger.

The initial reception (and even sales!) of More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI has been very gratifying and exciting. Perhaps the most fun thing so far was getting a chance to participate in an episode of

’s podcast in which he explored the challenge of getting young people to do their homework now that a homework machine is accessible on every computing device. I highly recommend checking out “Playboy Farti and His AI Homework Machine.”As always, I appreciate everyone taking the time to read and support this work. If you have anything to say about how you respond to book reviews or AI homework machines, please, let’s talk about it in the comments.

See you next week,

JW

The Biblioracle

I’ve got 4 books left to read for this year’s TOB. It’s my favorite book event and I too started reading your column as a result. But I did not know that The Biblioracle started as a TOB thing.

I always find at least one of my favorite books of the year at TOB. This year it is “The History of Sound” by Ben Shattuck. What a beautiful book! It’s a book of short stories taking place in New England over the last 300 years focusing on nature and music. What makes it unique is each topic has 2 paired stories from 2 points of view. Ok no more! I have to save my thoughts for the Commentariat where, incidentally, I have made more than one friend in real life.

I’ve long been a fan of the ToB. I usually read and recommend the final four-ish to friends who think I have great insight on books. I tell them “I just pulled it from this annual competition, you should check it out.” They respond with “Whatever. You have great taste for books.”