When I was a child, I was frightened of our big midwestern thunderstorms, being particularly apprehensive when I was otherwise trying to sleep, lightning searing through my firmly shut eyelids, thunder rattling my bedroom windowpanes. Those storms felt apocalyptic to me, surely the product of an anger I could not fathom, which appeared directed at me.

Even when I was old enough to understand the physics of thunderstorms, in order to calm the irrational firing of my limbic system, I would tell myself the myth once relayed to me by my grandmother, that the lightning was angels playing with flashlights, and thunder was angels bowling.

I never believed it as a literal truth, not even as a child, but conjuring that imagery as it seemed like the world was crashing down around me provided some measure of comfort. When a particularly intense clap of thunder was accompanied by picturing an angel leaping in celebration after bowling a strike, the image was a soothing distraction.

Reaching for narrative as a way to explain, control, or cope with an uncertain and inexplicable world is as human as it gets. Rather than having to grapple with the unknown and unknowable, we can attach a story. Sure, these stories are often literal myths, but if you believe in a world overseen by a benevolent and loving god, but nonetheless experience that world as a place of sin and suffering, you’re going go asking why. The answer is a narrative: You see things were incredibly groovy, but there was this serpent and an apple, and well…Believing some version of this story is perhaps preferable to a universe of indifference where you, the individual, are meaningless.

As a reader, writer, and writing teacher, I love thinking about the way narratives work in our lives, and the election of the past week has given great fodder for that thinking.

The story of playful angels I clung to in order to temper my fear of thunderstorms was using narrative to self soothe, to tell a story that distracted me from my reflexive (and largely irrational) fear.

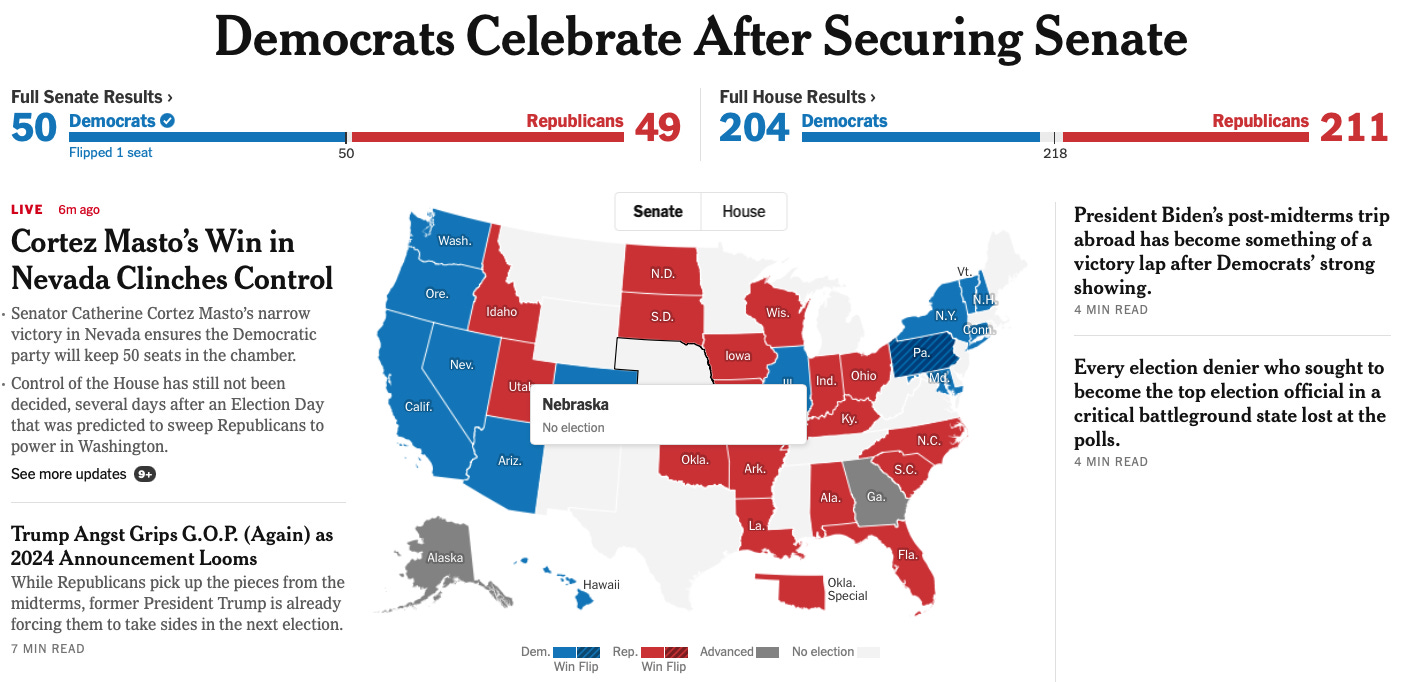

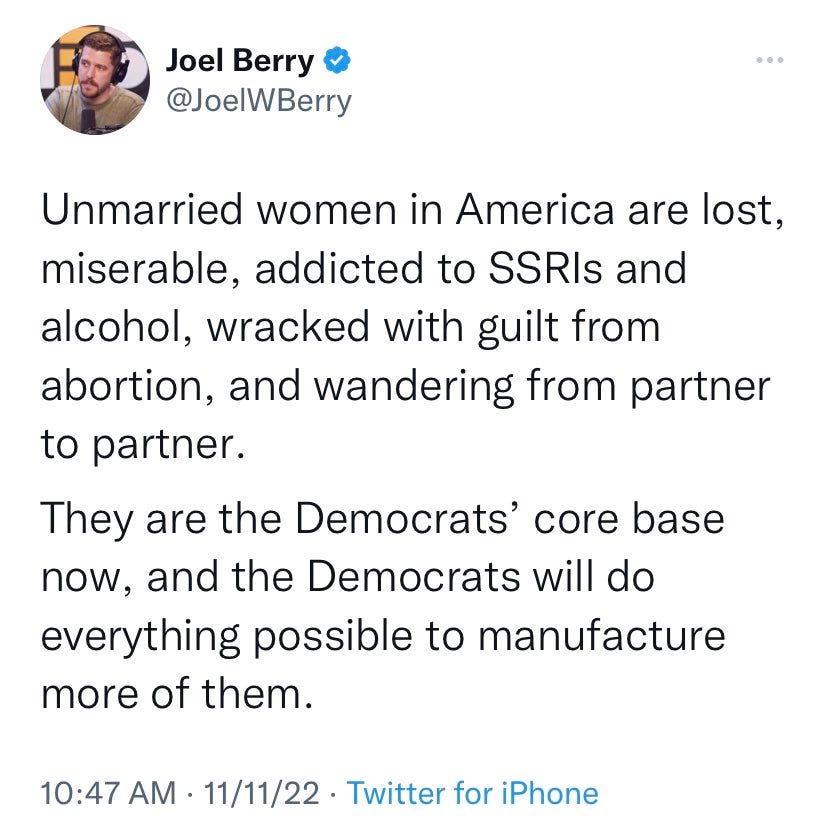

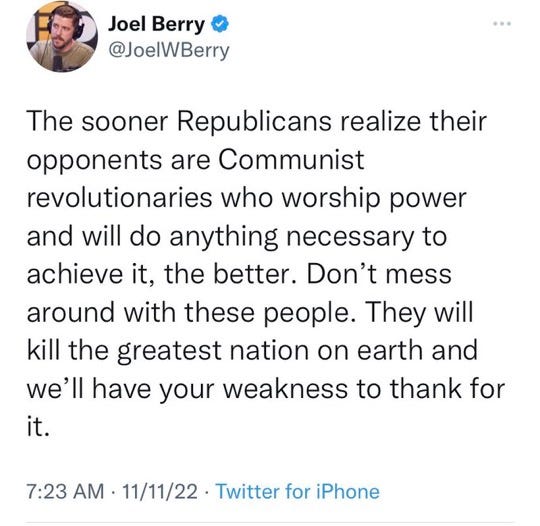

This is what is happening with this gentleman, who is the managing editor of The Babylon Bee, which bills itself as the conservative alternative to The Onion. He is deeply upset about the outcome of the election and is telling himself a story in order to make himself feel better:

No matter that these are two different stories, the common thread is not that he may be out of touch with the prevailing sentiments of the populace, but that the world is haywire, and only he can see it clearly.

This sort of reaction is easily mocked as the cartoonish fever dream of an extremist, but in the election’s aftermath of the election, I’ve seen a similar pattern among some of our nation’s leading, ostensibly centrist political and cultural observers, the people who help craft the narrative the rest of us are asked to believe.

While the examples of this phenomenon are almost too innumerable to name, and includes vast swaths of the mainstream political press, I want to focus on one particular figure who I think is just the absolute worst on this front.

(For more background on the problems with how the mainstream press covers politics, see

on why "The Political Press Needs a Time Out.")These two stories were written by the same man ten days apart.

In the first story, David Brooks is explaining why Democrats are about to be washed away in the impending “red wave” of the election.

In the second story, Brooks is explaining why that didn’t happen. In both pieces, while he appears to ground his opinion in analysis, in reality, each is firmly in the realm of almost pure narrative, a story that seeks to explain the world in a way that allows us to understand and grapple with the inexplicable.

The inexplicable thing Brooks is grappling with is the persistent popularity of Donald Trump and the political movement he spawned. Brooks has been clearly and vocally anti-Trump since prior to the 2016 election.

He reaches for narrative to try explain why Republicans seemed to be in such a favorable position prior to Election Day.

It is important to remember that what Brooks writes of on October 20th was never real. Nothing shifted in the last two weeks of the election. The boogeyman he envisioned was entirely invented. One would think that realizing the thing you thought was real didn’t actually exist would trigger a deeper reconsideration, but if you think that, you are not truly familiar with the oeuvre of David Brooks.

Brooks may be anti-Trump, but he is also anti-other things, including being anti-woke, which has left him vulnerable to believing that the extreme right narrative about what’s going wrong with America that he parrots in the above paragraph, may have actual salience with the swing voters who would tilt the election in favor of the Republicans.

But that didn’t happen. There was no red wave. It turns out that the moral panic fomented by the same people who want to ban books because they have gay people in them, is not based in anything real, something lots of people (including yours truly) have been saying for months and months. Republicans spent $50 million trying to get voters enraged about the existence of transgender people. Fortunately, there aren’t enough hateful bigots to swing full-control of Congress.

How does David Brooks deal with this change of story? He self-soothes, with a narrative of his own from his Nov. 10 column.

I find his coping strategy fascinating because rather than coming to the conclusion that things like cancel culture and wokeness either don’t exist, or have salience only at the margins of particular elite spaces - that people like David Brooks pay disproportionate attention to - he tells himself a story about how all these things he’s afraid of have receded.

It is a truly child-like way to attempt to understand the world.

Deep down, I wonder if this is as unconvincing to Brooks as it should be to his readership, but I fear neither is true because while Brooks is anti-Trump, he also is very much pro-status quo. He is dedicated primarily to a project that keeps people like him in positions that allow them to influence our national narratives. In this way, Brooks’ columns serve as a kind of fodder to continue to the support the narrative of a kind of intelligentsia to which he belongs, and which should listened to, no matter how often they are wrong.

Look, here’s where I’ll come clean and admit to my longstanding grudge against David Brooks and what he stands for, a grudge that has included the publication of one of my personal favorite pieces of parody, “David Brooks Also Eats Cereal.” (Click that link to see the full piece.)

My David Brooks haterade collection also includes a, cough…somewhat more obsessive piece…cough, a short story titled “The Road to the Road to Character”, in which I try to imagine the interior life of a man who both attempts to act as a kind of national conscience from the perch of his column in a major newspaper, but who also dumps his wife in order to convert to quasi-Christianity and marry a research assistant who is younger than his children.

Consider that narrative my attempt to understand how a man who is so wrong, and so flawed (in ways we all are, perhaps), nonetheless maintains such status as someone worth listening to.

Back in 2020 at Inside Higher Ed, I wrote about “our pundit problem,” and why these dynamics are so damaging to public discourse. The pundit - and Brooks is a perfect example of a pundit - spends much time trying to predict the future, often using (a wholly imagined) narrative as a source of evidence for this prediction.

As seen with Brooks on this year’s election, when his narrative fails, he retrenches around another narrative. I ask how anyone could read the following paragraph from Brooks’ column on the fever breaking and see it as anything other than wishful thinking.

Brooks is attempting to craft a narrative that moves the nation past Donald Trump. I don’t exactly blame him. I would love to be rid of Trump myself, but the malevolent forces Trump has tapped into predate the man and will outlive him as well.

I wouldn’t be so ready to write Trump’s specific political obituary either. How many times has Michael Meyers returned from certain death in order to terrorize Jamie Lee Curtis in the Halloween series? Narratives always have space for a comeback.

We should resist being soothed by the narratives people like Brooks peddle, narratives that flatter people like David Brooks and discount the experiences of the voters - particularly the young people - who are moving this country in a new direction.

I’ll admit that as someone older and established, those new narratives can make me feel uncomfortable and unmoored, but we owe it to ourselves to steer clear of comforting stories that are really no different from lies.

Links

At my Chicago Tribune column this week I explore the upcoming auction of some of Joan Didion’s effects. It’s not too late to get your hands on a piece of modern art, or even a paper clip.

Over at LitHub you can read short interviews with the authors of every National Book Award nominated book.

A Michigan community has literally voted to close its library, rather than to allow it to shelve LGBTQ books.

The New York Times and the New York Public Library have collaborated to produce a list of the best children’s picture books for 2022.

Debutiful, a website dedicated to highlighting debut authors, has named its best book debuts of 2022.

One of the most persistent American narratives is that rich people are uncommonly smart or capable. That myth is being busted this week thanks to Elon Musk’s flailing as he tries to do whatever it is he’s trying to do with Twitter, and the sudden bankruptcy of cryptocurrency exchange FTX and the disgrace of its founder, Seth Bankman-Fried.

Recommendations

I’m all caught up on people requesting reading recommendation, which gives me a good chance to recommend Christine Sneed’s piece from earlier this week that recommends Jim Harrison’s The Woman Lit by Fireflies.

I’ll add my recommendation of Christine’s newest book, Please Be Advised: A Novel in Memos, a very funny sendup of office culture.

Paid subscriptions from those who can afford the cost are what keep this newsletter free and accessible for all. Not particularly capitalist of me, but it’s working okay for all involved so far.

I honestly feel so much better now that this election period has passed. I’m going to go out and enjoy that feeling for the rest of the day. I hope you’re doing the same.

John

The Biblioracle

What you call "haterade" I call accurate analysis. As a former journalist, I can't thank you enough for trying to remind people that journalism *isn't supposed to be about what's going to happen.* It's supposed to tell us, accurately, what did happen and what is happening, and do actual reporting to try to understand why and what it's effects are. Bless you. You may have saved what little hair I have from being pulled out.