Recommendations 8/1/2021: The power of narrative.

Facts can't dent a story people want to believe.

I have not had sufficient time to develop a purely books and reading-related discussion for this space because I have spent an unfortunately large portion of my week attempting to get The Atlantic and one of its writers (Caitlin Flanagan) to correct an egregiously incorrect and deeply unfair and hostile article.

Flanagan was writing to register her disagreement with a decision by the University of California system to end the use of SATs as part of their admissions criteria. In the article, Flanagan made numerous misrepresentations of UC’s admission policies and practices. She also outright accused the UC administrators of ignoring the data and the needs of minority students, and instead ending the use of the SAT because it would be good PR on the social justice front.

Flanagan literally accuses the UC of lying about their reasons for the change. A pretty darn serious charge.

I won’t recap what I’ve written elsewhere and that you can read if you’re curious, but I knew that Flanagan was 100% wrong about her interpretations of the available data. I never know how many people who read me here are familiar with my other incarnations, but for a decade I’ve been writing about higher education at Inside Higher Ed. For my book, Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities, I went pretty deep on standardized tests and what they do and don’t mean.

I know I’m far more knowledgable about these issues than the average magazine journalist like Flanagan, but I also know that I wouldn’t go anywhere near calling myself an expert on the SAT or college admissions, which is why I went looking for actual experts who also might have read Flanagan’s screed.

There were many who were attempting to get Flanagan and The Atlantic to address the errors. I amplified some of them in my piece.

After four days of cajoling, some minor amendments were made to the article, but the article and its implications, that the SAT is an aid to minority students applying to the UC system, and that administrators dropped them for craven reasons, still stand despite that being empirically incorrect, as demonstrated by decades of research and, more importantly the fact that in a year without using the SAT because of COVID-related restrictions around taking the test, the UC just admitted its most diverse cohort of students ever.

Obviously I’m still not over it, or I wouldn’t be worrying about it to you good folks. Taking a half step back and reflecting for a moment to try to make it relevant to why you might’ve signed up for this newsletter, it made me think about how issues of expertise and authority intersect, and what that means to readers who would like to be able to trust what they read.

I don’t know about you all, but when I read a book put out by a reputable publisher or a piece in a magazine as venerable as The Atlantic, I tend to trust that what I’m reading is accurate and true, within the natural realm of human foibles of course. Mistakes happen, but writers try their best to avoid them. That’s how I was taught anyway.

But we (okay, I) shouldn’t be so naive. Nonfiction books are famously not fact checked, and some of our most popular pop social science writers play very fast and loose with the data in service of telling a good story that people will want to buy.

For example, I have read Malcolm Gladwell’s books with great fascination, but it is also important to know that often Malcolm Gladwell is full of s__t. Something like Gladwell’s famous 10,000 hour rule of practice to achieve mastery, feeds into a general belief that indeed, it takes time to become an expert, but the 10,000 hour rule has been debunked over and over again.

And yet, despite this evidence many millions of people will continue to insist that the 10,000 rule is true.

Gladwell gets away with this because he couches his pseudo social-science in narrative, either narratives that people think are true, or would like to be true. Facts have no chance against a good story.

Caitlin Flanagan, a highly skilled writer, knows this, which is why she did not write a dry recitation of the available data on the impact of the SAT on admissions to the University of California system schools. Instead, she invented a narrative of perfidious administrators bowing to political correctness. The facts of the matter were irrelevant next to the narrative she wanted to inject into the conversational bloodstream, which is why even though they have now corrected (only) some of the errors and the logic of her argument is destroyed, the message of the piece is unchanged.

As someone who cares about this stuff, it’s disheartening. I’m a subscriber to The Atlantic, and think some of their contributors are among the finest journalists alive. It’s one thing for Caitlin Flanagan - who, despite her talent as a writer has demonstrated herself to be a hack - to dig her heels in, but for the institution to fail to correct the error under their banner shakes my faith in whatever else The Atlantic is putting into the world.

What can readers do about it? The first thing is to be at least a little wary when you sense that someone is feeding you a narrative that might be light on evidence to support it. This is particularly difficult to do when it’s a narrative that jibes with our existing world-view, but that makes it even more important to keep some of our guard up.

The second thing is that when you know that someone is promulgating B.S. through influential channels, you do your best to stand up and push back. No, Flanagan has not pulled her piece or apologized for her errors as someone should, but maybe the fuss will make her think twice before she tries something similar again.

Thanks for listening. I feel a little better.

Links

In this week’s column I extol the virtues of the new Hulu documentary Summer of Soul on the 1969 Harlem Culture Festival and lament how significant swaths of our most important moments of American history and culture have been hidden away.

The Booker Prize has released their longest of nominees, and there’s a few Americans on it.

Shirley Jackson is one of the most fascinating figures in literature, and her collection of letters looks like it’s a must read.

Looking for a thriller? The Washington Post has five new ones they recommend.

The New York Times has 11 books they think we should know about for August.

Reading companion of the week

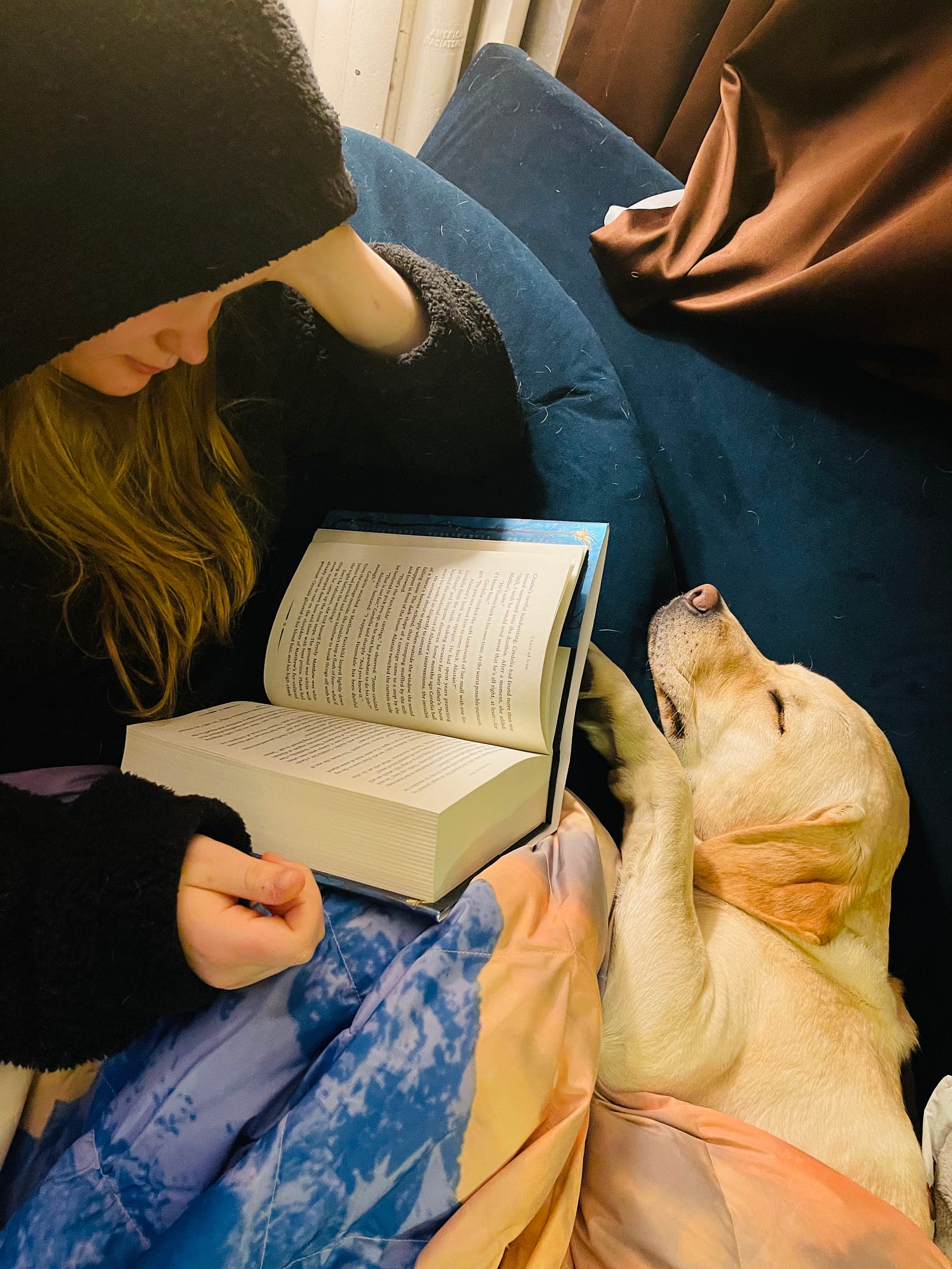

Zaffy looks settled in for a long read of a big book with her teenager.

Send a picture of your favorite reading companion to biblioracle@substack.com

Recommendations

All links to books on these posts go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago. Continued steady progress on our annual tally: up to $116.55 for the year. Outstanding progress.

If you’d like to see every book I’ve recommended in this space this year, check out my list of 2021 Recommendations at the Bookshop.org bookshop.

As always, recommendations are open for business.

1. Among the Missing: Stories by Dan Chaon

2. Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir

3. Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

4. Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich

5. The Start-up Wife by Tahmima Anam

Karla H. - Grinnell, IA

I think Charles Baxter’s Saul and Patsy, a novel of good Midwestern folks, will wind its way into Karla’s heart.

Either folks are not sending requests or they’re getting trapped in my email filter, but that’s all for this week.

See you all next time,

John

(The Biblioracle)

Whomever controls the narratives controls the public at large. Mis-representations, mis-information, and downright lies are all interspersed with some actual facts to form narratives to form consensual public opinion. One must beware of this when coming to any conclusion on public affairs. I hardly trust anything these days without proper vetting. It saves me much distress.

I’m shaken. It seems like it’s getting harder and harder to know what and who we can trust. What can the average thinking person do about this? I don’t think it’s realistic for readers to have to check the sources of nonfiction books that we read. Or is it? Shouldn’t that be the publisher’s task? I’m thinking about a fascinating and eye-opening book I recently read, Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, by Caroline Criado-Perez. Now I wonder how much of what I read in that book is true. As previously stated, I’m shaken.