I must confess, the 4th of July ranks low on my list of favorite holidays, the chief reason being the neighborhood fireworks, which make one of the dogs (Truman), tremble with fright, and also which started a good week ago, and will of course continue well into the middle of the month.

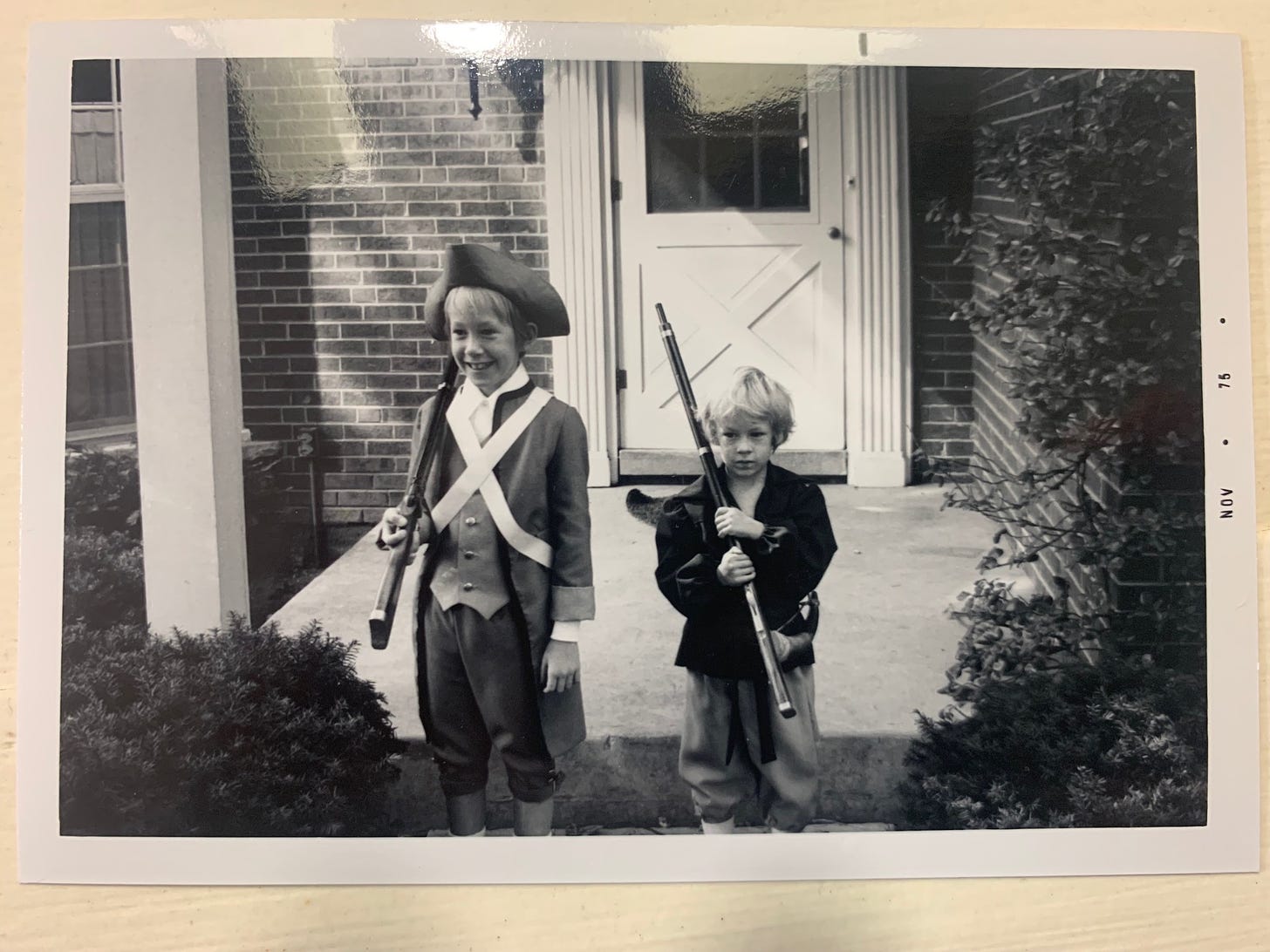

When I was a kid, it was one of my favorite holidays. We lived maybe a hundred yards from my hometown’s (Northbrook, IL) parade route, and I looked forward to furiously scrambling for the penny candy people would throw from the floats. The best Tootsie Roll is the Tootsie Roll snatched from the ground moments ahead of some other kid. For the country’s bicentennial parade in 1976, my older brother and I got to march in wearing our Halloween costumes that had been made by Grandmother Biblioracle the previous year. Brother Biblioracle was a colonial “minuteman” and I was Davy Crocket (or maybe Daniel Boone?), musket, powder horn, coonskin cap and all.

My relationship to patriotism was uncomplicated when I marched in the 1976 bicentennial parade. I’d been told the country was an unalloyed good. I said the pledge of allegiance at the start of every class. I deeply envied my brother’s red, white, and blue Schwinn ten-speed. These attitudes would not be unusual for a kid growing up in an almost exclusively white suburb in 1970’s America.

I still consider myself a patriot, but it’s much more of the, “criticism is necessary to hold the country accountable to its values” variety.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

In an essay titled “The Great American Joke,” Louis J. Rubin identifies the embedded in the Declaration of Independence as perhaps the first American joke, and an example of what would make American humor particularly American, the gap between articulated ideals and the actual state of things: “The difference between the ideal and the real.”

In his essay Rubin observes:

This verbal incongruity lies at the heart of American experience. It is emblematic of the nature and the problem of democracy. On the one hand there are the ideals of freedom, equality, self-government, the conviction that ordinary people can evince the wisdom to vote wisely, and demonstrate the capacity for understanding and cherishing the highest human values through embodying them in their political and social institutions. On the other hand there is the Congressional Record— the daily exemplary reality of the fact that the individual citizens of a democracy are indeed ordinary people, who speak, think and act in ordinary terms, with a suspicion of abstract ideas and values.

That suspicion is ever present. We have seen a particularly bad flare-up recently, in terms of this battle over the ideal and the real.

There are always some folks who seem to believe that examining the real is somehow a threat to the ideal. Speaking of this notion and Davy Crocket simultaneously, an event scheduled at the Bullock Texas State History Museum to celebrate the newly released book, Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth, was cancelled following pressure from elected leaders, including Texas governor Greg Abbott (who sits on the museum board) who do not care for the book’s re-examination of the mythos surrounding the Battle of the Alamo.

These sorts of incidents are linked to other campaigns which seek to ban the teaching of the 1619 Project, and other anti-racist materials, or even materials which discuss race in schools. There seems to be a fear of telling the story of a more complicated America and a preference for the myth.

I do not know how to read these acts of censorship as anything other than pro-ignorance and anti-American. The introductory essay to the 1619 Project by Nikole Hannah-Jones is one of the most profoundly patriotic pieces of writing I’ve ever read. Its first line is: “My dad always flew and American flag in our front yard.”

From there, Hannah-Jones discusses her youthful confusion about her father - who had served in the U.S. Armed Forces, but still was subject to the injustice of segregation - and his patriotism. She did not understand why he wasn’t more embittered, more skeptical of the American promise. She says, “That my dad felt so much honor in being an American felt like a marker of his degradation, his acceptance of our subordination.”

She later reconsidered that earlier opinion: “Like most young people, I thought I understood so much, when in fact I understood so little. My father knew exactly what he was doing when he raised that flag. He knew that our people’s contributions to building the richest and most powerful nation in the world were indelible, that the United States simply would not exist without us.”

That someone could read this statement of pride in one’s people and one’s nation as somehow un-patriotic, or dangerous to schoolchildren is mind-boggling to me. (In fact, I think very few of the people who wish to ban the 1619 Project) have actually read it.) I do not know what anyone has to fear about acknowledging the truth, that the United States would not exist without the contributions of its Black people. The struggle first for Black liberation and the ongoing struggle for equality are indeed patriotic acts, efforts to bring the country closer in line to its ideals: all created equal; life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is worth asking why so many appear to be so afraid of these conversations. Why they think there is something to lose by even having these conversations.

This is what I think about on Independence Day, as we honor this complicated country.

Links

It’s the 50th anniversary of the film, Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, which is of course adapted from Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. This piece shares a bunch of stuff you probably didn’t know about the film and its participants. Like, did you know that Charlie grew up to be veterinarian in real life?

Bethanne Patrick, one of my favorite BookWorld figures, tells us 10 books to read in July.

In my column this week, I provide a list of my own, my favorite books of the first half of the year.

Charming profile of Francine Prose, who has written some of my favorite books, e.g., Mister Monkey, and Blue Angel.

Reading Companion of the Week

Like many reading companions featured thus far, Shadow appears to also be a reader.

Send pictures of your reading companions to biblioracle@substack.com.

Recommendations

All links to books on these posts go to The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago. The tally up to $80.45 for the year. Can we make it to three digits by the end of July?

As always, recommendations are open for business. Supply is still on the low side, so wait is minimal. If you’ve sent one if the relatively distant past and I didn’t feature it, send again!

1. Maxwell's Demon by Steven Hall

2. Attrib. and Other Stories by Eley Williams

3. The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris

4. My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh

5. A Gate at the Stairs by Lorrie Moore

Elizabeth T. - Hopewell, NJ

Been on a bit of a reading tear both in terms of volume and quality, and right at the top of the quality list is Morningside Heights by Joshua Henkin, who has a particular gift for making you feel close to his characters, even when on the page, a scene feels like a sketch. I’m also very fond of Henkin’s previous novel, The World Without You.

1. Geek Love Katharine Dunn

2. The Firekeeper’s Daughter by Angeline Boulley

3. Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman

4. The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates

5. Wintering: the Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times by Katherine May

Susan R. - Munising, MI (on behalf of her book club)

A book club that sought out Geek Love can handle another of my all-time favorite reading experiences Skippy Dies by Paul Murray.

1. Maybe You Should Talk to Someone: A Therapist, Her Therapist, and Our Lives Revealed by Lori Gottlieb

2. Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

3. The White Tiger by Aravind Adiga

4. In the Distance by Hernan Diaz

5. Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption by Bryan Stevenson

Zach M. - Chicago, IL

For Zach a book that bowled me over when I read it, by an author I can’t wait to see what he does next, A Brave Men Seven Storeys Tall by Will Chancellor.

Sympathies to all the fireworks-averse dogs out there,

John

(The Biblioracle)

My feeling exactly, in the words I wish I had put together. The 1619 Project podcasts still reverberate and bring me to tears. The ideal is still the goal.