It’s been a bad week for supposedly brilliant people.

Elon Musk’s flailing about as he tries to do whatever it is he’s trying to do with Twitter has become the stuff of national mockery.

Elizabeth Holmes, founder of fraudulent blood testing company Theranos, was sentenced to more than 11 years in prison for perpetrating that fraud.

The continued fallout of the collapse of cryptocurrency exchange FTX revealed both the incompetence and apparent duplicitousness of founder Sam Bankman-Fried. John Jay Ray III, the man in charge of unraveling the mess that was Enron, now in charge of unraveling the mess that is FTX, called the situation, “unprecedented.”

This exhaustive report from the Wall Street Journal will catch you up on the full saga, and to call it a saga perhaps understates things.

How could such brilliant people experience such calamities?

Even as Holmes was moments from being sentenced to prison, the judge felt compelled to recognize her “brilliance.”

Musk purchased Twitter for $44 billion, significantly overpaying to begin with, and driving the valuation lower on a daily basis.

At its peak, Theranos was worth $9 billion. Sam Bankman-Fried appears to be suddenly $16 billion poorer, the investors in his cryptocurrency exchange, have been wiped out.

This is supposed to be a newsletter about books, so I want to think about some of this stuff through the lens of books I know.

The book on Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos has already been written, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies at a Silicon Valley Startup by John Carreyrou, a former investigative reporter at the Wall Street Journal whose work at the paper ultimately punctured Holmes’ fraud.

Michael Lewis (The Big Short, et al) had reportedly been embedded with Bankman-Fried for six months prior to the meltdown and has sold the movie rights to the as yet unwritten book.

I would bet dollars to donuts there are no fewer than half a dozen proposals for books on Musk’s Twitter tenure currently circulating through publishing houses.

I suppose when these books inevitably appear we will get the “full story” of what has happened in each of these cases, but when it comes to FTX and Sam Bankman-Fried, I feel like it’s a story we've probably heard a bunch of times before, a story that part Theranos (Bad Blood) part Enron, The Smartest Guys in the Room.

In each of these cases, the smartest guys (or gals), have supposedly found a loophole that no one else has seen that paves the way for success of previously unimaginable heights. For Enron, it was so called “mark to market accounting” which the company used to book future profits on their balance sheets at the moment a deal was signed, no matter than the actual future profits were as yet unknown. This drove up Enron’s valuation, enriching executives and other employees who held stock options.

While publicly, Enron was being feted as the smartest guys in the room, the reality behind the scenes is that they were consistently performing poorly, and the fraudulent bookkeeping ultimately didn’t hold up against he dedicated scrutiny of the investigative reporters. The company winds up in bankruptcy, the executives in jail.

With Theranos, we add a couple of twists to this story. We have Holmes, the brilliant college dropout who is motivated to transform patient care through this new technology that she apparently is able to conceive despite having no background in the relevant science. Sure, Theranos is becoming hugely valuable as it racks up investor capital, but deep down, Holmes is an altruist, you see.

Holmes had an almost messianic belief in her own vision - a vision, it is important to remember, that was purely fantastical. She didn’t even apologize for her actions until the sentencing, and even then frames her wrongdoing as a failure to realize her hopes and dreams, as opposed to her ethical or criminal lapses.

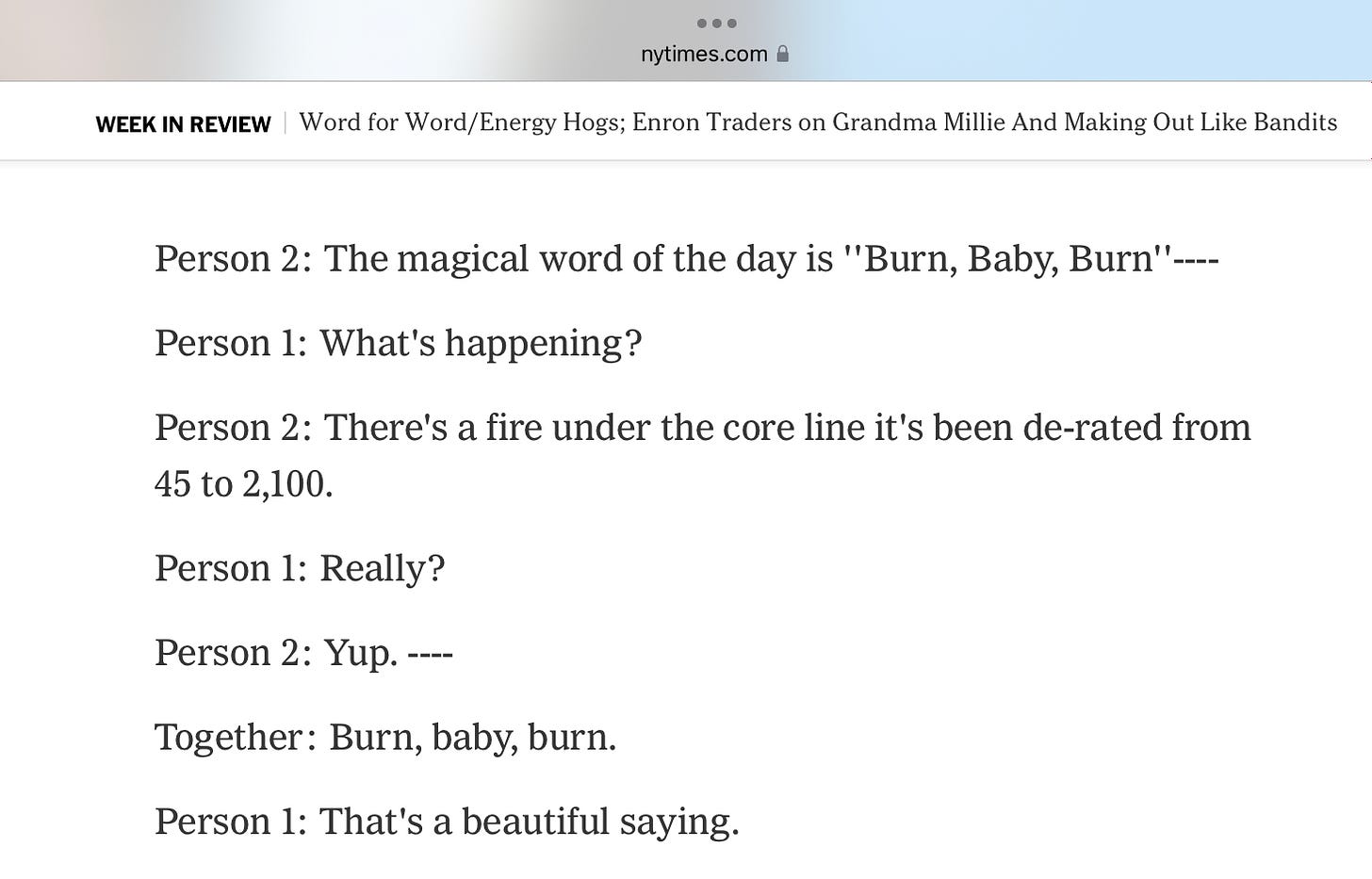

The Enron executives became avatars of a kind of rapacious greed that was decried following the company’s downfall, but which pervaded the company while it was flying high. Perhaps some of you remember the revelation of the conversations of Enron traders celebrating the hardships customers were experiencing, which would lead to an increase in value of Enron’s contracts for providing power, like this one between two traders who were cheering on a wildfire that damaged transmission lines.

In the intervening years, by the time we get to Theranos, Holmes uses the cover of doing good for the world of healthcare, and her wunderkind status as a shield, going on Jim Cramer’s Mad Money TV show to hit some softball questions even as Carreyrou’s reporting had revealed the fraud.

Unlike the traders at Enron who appeared to have no ethical compasses whatsoever, the actual scientists and engineers working at Theranos were hugely dedicated to trying to make Holmes’s fantasy come to life.

Because of her altruistic framing, and her wunderkind status, and her protective circle of eminence gris on her board (James Mattis, George Shultz, et al), Holmes outran her fraud for an unbelievably extended period, but ultimately couldn’t outrun the fact that her technology was never going to work.

Sam Bankman-Fried took these elements to another level, crafting a mythology about himself and his motives that allowed him to amass and lose his own fortune, and the fortunes of others. It has to do with a few things: 1. Bankman-Fried showered money among Democrats, and even pledged to donate $1 billion for the 2024 cycle to defeat Donald Trump. 2. His youth and wealth gave him a wunderkind status. 3. He was closely associated (and funded) the Effective Altruism movement.

Prior to the FTX/Bankman-Fried meltdown I had only a vague notion of the Effective Altruism movement, but having become unhealthily fascinated with this thing, I’ve fallen down a bit of a rabbit hole, and maybe this is my age or my cynical nature talking, but this stuff, particularly its related concept of “longtermism” is what Mrs. Thompson, my strict (but loving!) 7th grade teacher would call “nonsense.”

At its core, the underlying principles of Effective Altruism are unobjectionable. Essentially they advocate for donating significant portions of your income (at least 10%) to the causes and organizations that will do the “most good.” Good is viewed as a quantifiable metric, rooted in human well-being. For example, if you have $5000 to give away, and your choices are donating it to your college alma mater or buying anti-malaria nets in the developing world, you buy the anti-malaria nets because you will be intervening in a way which will save actual lives.

Fair enough, I suppose. No one would argue that all philanthropy is created equal, and doing some calculations into how much good you can do within the limits of your resources seems only sensible.

But Effective Altruism isn’t just a strategy for guiding philanthropic donations, it is a philosophy of life. Oxford philosopher William MacAskill is the single figure most associated with Effective Altruism, and the person who apparently convinced Sam Bankman-Fried to use his framework to govern his life and business decisions. MacAskill’s book, Doing Good Better: How Effective Altruism Can Help You Help Others, Do Work That Matters, and Make Smarter Choices about Giving Back, is a sort of primer for Effective Altruism, and promises to help people make “data driven” decisions about how to live lives that will benefit humanity. These decisions include things like affirmatively choosing high-paying careers in arguably non-helpful fields (like finance) provided those jobs allow you to make gobs of money which you then donate in effectively altruistic ways.

One of those ways is apparently to give to the Center for Effective Altruism, which reported almost $22 million in revenue in the most recently available tax year information.

Cryptocurrency is a famously unregulated and scammy place, but in interviews, Bankman-Fried spoke about his motives to take advantage of his apparently innate ability to make money in the space to do good by doing well. The truly fawning coverage of Bankman-Fried prior to the collapse would be gobsmacking, if we hadn’t witnessed something similar with the previous wunderkind, Elizabeth Holmes.

If they weren’t brilliant, how could they be so rich and successful so young?

But as you peel back the onion a bit and considering the underlying precepts of Effective Altruism, it begins to looks like a way for people with liberal sensibilities to feel good about becoming obscenely rich because hey, we’re altruists.

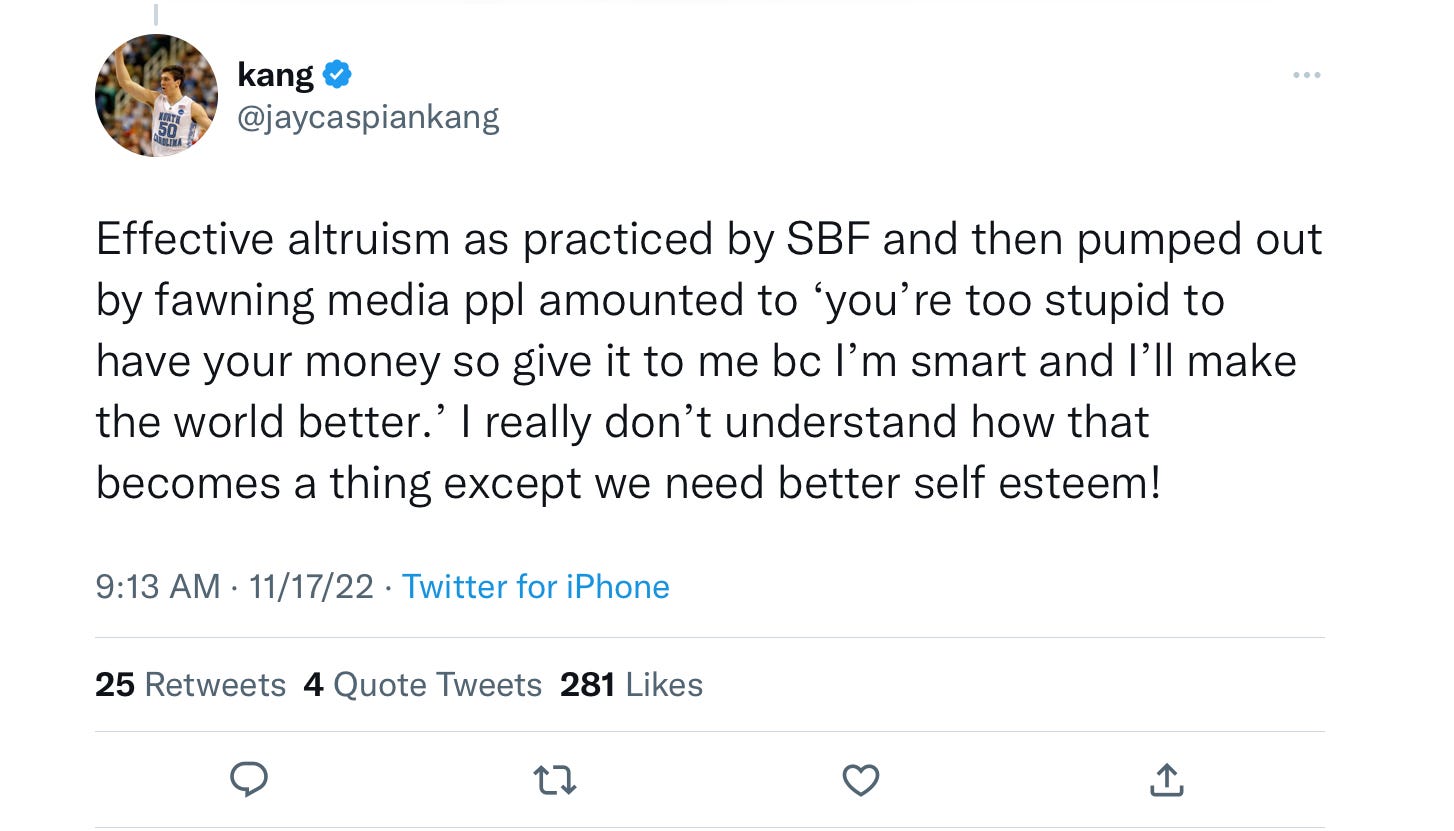

I’ll save time and let a Jay Caspian Kang tweet speak for me on this front.

There is some kind of structural incentive to validate nonsense when it’s accompanied by charts and math-ish seeming calculations. When someone tells you that your thousand dollars could save a life in Africa, you suddenly feel like a piece of garbage for thinking about giving that money to - using a non-random example - The Avian Conservation Center located in Awendaw, South Carolina.

What is an injured hawk’s life as compared to a human being? Sure, raptors are an incredible species whose existence is threatened by the encroachment of people on their territories, but we’re people. They’re birds. Obviously we’re more important.

The sound underlying core of EA - try to do as much good as you can - gets weird when the philosophy makes claims to providing true answers to questions like “What does it mean to live a good life?” The rationalist community - with which EA is associated - believes that life can be '“hacked” and the correct course of action in life is to determine the correct course of action. There is always a best course that can be determined through weighing the data, and calculating the odds.

When MacAskill extends EA to what is known as “longtermism,” as he does in his book, What We Owe the Future, things get really hinky. Longtermism takes the position of Effective Altruism and asks, “What if we also think about the gajillion people yet to be born as having equal moral weight as everyone living today?”

If that sounds odd to you, it’s because it is. It is consequentialism ad absurdum, the famous ethical trolly problem of throwing a switch on a track so it will kill one person instead of five people, and increasing those five people to an infinite population of future humans. If you want to read a lengthy takedown of longtermism, I suggest this piece by Peter Wolfendale reviewing and responding to What We Owe the Future. But I don’t need a bunch of data to understand a cockamamie idea when I hear one.

As a movement, what Effective Altruism seems to have become is a way for people with generally liberal politics, combined with technocratic mindsets, and a desire to justify becoming rich without feeling super guilty about it, or becoming tagged as a rapacious asshole like those chuckling monsters at Enron, to free themselves from scrutiny.

Kang again:

I would not argue that the Effective Altruist movement is responsible for Bankman-Fried’s alleged fraud, but it certainly gave intellectual and moral cover for his actions, and made this kind of fraud more likely to occur. Cryptocurrency is a famously difficult area to understand, but here were Tom and Giselle, Larry David, and others vouching for FTX as a way to get rich, like them.

The problem of allowing the extremely wealthy to dictate philanthropic spending and its implications on public policy predates the EA movement as well. For better than a decade, Bill Gates has essentially controlled what gets researched in education. His support of the Common Core State Standards paved the way for their rapid adoption. These things have been disastrous, not just because Gates’s meddling in education has proven ineffectual at best and actively harmful at worst, but because it has put one man and his beliefs at the center of what should be a broader, democratic conversation.

Our takeaway from these sorts of occurrences should be to reject the influence, and even the existence of billionaires that hold so much sway. Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World by Anand Giridharadas demonstrates how people of immense wealth use the sheen of philanthropy to ultimately simply protect their wealth and status, often to little public benefit, even when they’re ostensibly giving away lots of money.

Bankman-Fried is simply the next level iteration, to use the sheen of philanthropy as an aid to getting obscenely wealthy in the first place.

I am not without sympathy for people who gravitate toward Effective Altruism, or even Sam Bankman-Fried himself, who seems genuinely psychically adrift in this series of text conversations with Vox reporter Kelsey Piper. He did not see himself as someone who would do such horrible things, and yet here he finds himself facing multiple criminal and civil probes.

He seems to have a moment of self-awareness, where he admits that he talked a good game because it made people believe he was a good, and trustworthy person.

To the extent that this seems to work inside our elite culture, perhaps it’s shame on us, and I include myself here, as I have often found myself silent in the face of stuff that I think sounds pretty bullshitty, but also comes packaged in ways that makes you feel like a bad person for criticizing, or which comes via people of a higher station, who deserve trust and deference because of that higher station.

I’m thinking here of something like Teach for America, which instinctively sounded bad to me: You mean we’re going to parachute in a bunch of white kids who’ve never taught before into high-poverty districts, primarily serving Black students, have them teach for a couple of years, and then replace them with another batch of newbies, and that’s going to help? Really?

But the people behind TFA had elite pedigrees, and the students joining came from places far more prestigious than my humble state university. They wanted to help, and what was I doing? You didn’t see me volunteering to go teach in a high poverty district.

As I’ve matured, I've become much less impressed with elite pedigree, and much more radical around the need for democratic messiness as a more sustainable and equitable approach than technocratic (faux) cleanliness, so I’m faster to channel Mrs. Thompson and call nonsense, nonsense, but even now, I’ll hesitate, because what if I am wrong?

What if those smart, rational, data-driven people have hit on the key to a happy, prosperous life of both individual thriving and service to others? I can see why Effective Altruism becomes attractive. Who doesn’t want answers to these impossible questions?

If, like me, you struggle with these questions, let me suggest Todd May’s A Decent Life: Morality for the Rest of Us. May is a philosopher from Clemson University, and was a technical advisor to television show The Good Place. May’s book walks readers through different ways of thinking ethically and morally, and does so in a way that allows the reader to wrestle with the questions, as opposed to proposing answers.

The extreme consequentialism of Effective Altruism is but one approach to life, one that when taken to that extreme can lead a person to do very bad things via an elaborate self-justification rooted in their original sincere desire to do good.

What Todd May reminds us of is that living a decent life is an ongoing struggle, just as it should be.

Links

At the Chicago Tribune this week, I have a little pop quiz about inflation and book prices. No cheating!

This week in absurd book bans. A district in Oklahoma has removed every graphic novel from its library shelves, just to be on the safe side, I guess.

Audible has named the 15 best biographies and memoirs of 2022.

The Morning News Tournament of Books long list has been announced, which means the short list of competitors is not far behind.

The Washington Post has named its 50 Notable Works of Fiction of the Year.

Recommendations

All books linked here are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Affiliate income is $312.80 for the year.

1. The Sewing Girl’s Tale: A Tale of Crime and Consequences in Revolutionary America by John Wood Sweet,

2. “Mutinous Women” by Barbara DeJean

3. “March” by Geraldine Brooks

4. Overstory by Charles Palmer

5. Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Sara S. - Lawrence, KS

For Sara, I’m recommending Annie Proulx’s family story, written in a hypnotic and unforgettable cadence, The Shipping News.

—

The reason I included the line about donating to the Avian Conservation Center is because I wanted to find an excuse to recommend Helen MacDonald’s H Is for Hawk to see why giving money to an organization dedicated to something orthogonal to human preservation can be a moral act even when weighted against human life.

But I couldn’t fit it in to the main text, so I’m just going to do it here. I’m recommending H Is for Hawk just in general, and just because.

Lordy. Maybe I have to start writing a mid-week newsletter too just so I don’t let everything I want to say build up into such epics.

Have a good week, one and all.

JW

The Biblioracle

Some very similar thoughts have been clunking around in my brain this past week. Thank you for putting them more eloquently into actual words.

Excellent. It all gets even weirder and more offensive when considering the full range of related TESCREAL faux philosophies, reaching full-blown eugenics. Here's a conversation I had with Emile Torres, who with Timnit Gebru came up with the acronym: https://youtu.be/FXeiDt8obD4?si=JTE5pAOFoCYfcBph&t=76