What’s up with the “trauma plot?”

The talk of the online literary world this week has been trauma.

Good times!

Parul Sehgal (formerly chief book critic at the New York Times and now at the New Yorker) kicked things off with a provocative and ranging argument in “The Case Against the Trauma Plot.”

Sehgal defines the “trauma plot” as a narrative in which character trauma is not only present, but central to the unfolding of the narrative, the way couples and courtship are central to the marriage plots of Jane Austen, et al. By its nature, the trauma plot narrative must be backward looking, as the whole point is to explore and then reveal the source of the trauma as a dramatic turn.

Sehgal has clearly had enough of the trauma plot, and she aims to convince others that they should feel similarly.

One of the reasons Sehgal stirred up so much sentiment is that she names names, including Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose series, Jonathan Safran Foer, Karl Ove Knausgaard, and even - brace yourselves - Ted Lasso.

Sehgal perceptively observes, “The second-season revelation of Ted Lasso’s childhood trauma only reduces him; his peculiar, almost sinister buoyancy is revealed to be merely a coping mechanism.”

I tend to agree, and I think the narrative impulse to put so much weight on the question, “Why is Ted the way he is?” makes for a less interesting story than “What’s Ted going to do next?” In a way, the trauma plot isn’t a plot at all as plot involves a series of events connected by causation, each leading inextricably to the next. The core event of the trauma plot has happened before the narrative even starts to unfold for the audience. A key element that’s driving the action is simply hidden from us the whole time, and once revealed it may deflate, rather than heighten narrative tension.

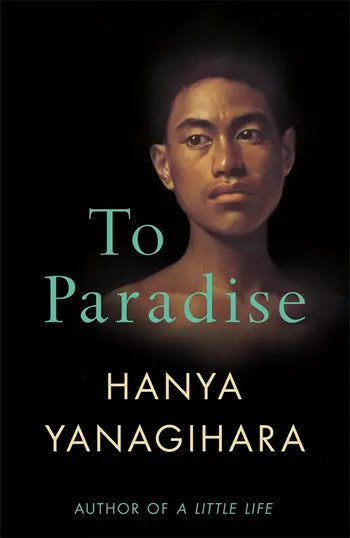

Sehgal’s essay is largely tied to the occasion of the publication of Hanya Yanigahara’s follow up to A Little Life, To Paradise. A Little Life is essentially a novel entirely about trauma, to the point where the trauma itself becomes fetishized. For those who fall under the book’s spell (I was one of them), it’s a wrenching reading experience that unfolds with a can’t-look-away horror. Once you fall out of its spell, however, the implausibilities and inconsistencies of the novel’s construction begin to gnaw at you. In hindsight, on an artistic/aesthetic/craft level I think the book is pretty dubious. On the other hand, I can’t deny the effect it had on me as I was reading it. This tension is why so many critics are now talking about Hanya Yanagahara’s new novel, which means, she must be doing something right in following her own artistic impulses.

With time and distance, the aims and limitations of Yanagahara’s approach in A Little Life become more apparent, and a number of critics beyond Sehgal have come to offer a corrective, most notably to my eye Andrea Long Chu writing at Vulture who made me wonder if there was something wrong with me for being bewitched by A Little Life when I read it.

I’m not a real book critic, but I got some thoughts…

It’s all interesting to me because I’m not well-read enough or smart enough to write a perceptive critical essay like Parul Sehgal or Andrea Long Chu, but I am just barely smart enough to take in what they’re saying and roll it around my own noggin for a bit.

On the one hand, I think Sehgal offers some very sound analysis that’s worth chewing on, particularly for writers as they craft their own narratives. On the other, if you look at it a certain way, I wonder if every narrative isn’t a trauma narrative. For Whom the Bell Tolls? Total trauma narrative. If you think about it, “trauma” is just a name for the bad stuff we all carry around with us. Calling it “trauma” and making so much of our personal trauma so public is perhaps new, but trauma’s presence stretches back to Eden when that serpent came offering an apple.

When a trauma plot rubs the reader wrongly it’s not so much the presence of trauma in a character’s backstory that is to blame, but a failure of craft. Trauma by itself cannot substitute for meaning.

We are not our traumas, and there is something a little dire about choosing to be defined by one’s trauma.

I do think it’s worth wondering why individual stories of trauma have so much salience in our culture, why it seems as though we can’t get enough of them. My thoughts are provisional and inchoate, but I wonder how much it has to do with the diminution and even collapse of our institutions: church, government, schools, communities.

In the immediate aftermath of the election of Donald Trump I wrote a post at Inside Higher Ed arguing that “we’re really going to need our institutions” because it was clear to me that he was a man intent on assaulting them. I had been struck by an exit-polling statistic that said two-thirds of voters did not think Donald Trump had the temperament or qualifications to be President, but twenty-percent of that group (essentially his margin of victory) voted for him anyway. This meant there was a significant number of people who deep down didn’t believe it mattered who the President of the United States is. If that’s not a lack of faith in institutions, I don’t know what is.

When we are left untethered to others, there’s not much choice but to turn inward, and without those institutions to provide support and solace our traumas are both more frequent and severe.

Those traumas have to go somewhere.

Potentially dubious generational broad brushing that I nevertheless feel might be true.

As a Gen Xer, I feel as though my life has been spent watching institutions once intact, crumble. I was born in the “Me Decade” and raised during the Reagan Revolution steeped in the ethos of Gordon Gekko’s “greed is good,” Gekko a character who is meant to be risible but became an object of emulation.

We were told that success is an individual enterprise and may involve stepping on a few spines along the way. Those who looked like they were opting out of that dynamic were called “slackers,” but you’ve got to wonder if they had the right idea as you look at the emotional toll on both the conquering and the conquered. In the aftermath of the most traumatic single event of my lifetime (9/11) the President told us it was our patriotic duty to go shopping.

And whatever trauma people of my generation have experienced has only been distilled to a greater potency for subsequent generations. The mysteries of increased rates of anxiety, depression, drug addiction and suicide should not be so mysterious when looking at the society that we’ve constructed for them.

As an official old, I am actually encouraged by the scenes of students across the country walking out of their schools this past week in protest of what they believe to be unsafe and unproductive learning conditions. Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo calls the push to open schools for face-to-face instruction “COVID perseverance theater,” acts that are untethered from what should be a straightforward logistical analysis: under the current set of circumstances is it less disruptive to learn in person or remotely? These students see institutions ostensibly tasked with the mission of protecting their interests failing them spectacularly.

Disagree with those students all you want, but I’m glad to see the seizing of agency, a refusal to be a passive subject of a trauma narrative, and instead be the characters who are going to write their own futures.

Links

My Chicago Tribune column this week is about how Norman Mailer is not being “canceled,” but he may have to be prepared to fade from prominence, while Joan Didion will achieve some measure of lasting prominence.

Also in Joan Didion discourse, I recommend John Ganz’s reflection on Didion’s life as a political conservative, and how public intellectual conservatism has changed over time.

Also at the Chicago Tribune, Christopher Borrelli looks at two new books about dealing with a significant source of trauma, work: The End of Burnout: How Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives by Jonathan Malesic and Out of Office: The Big Problem and Bigger Promise of Working from Home by Charlie Warzel and Anne Helen Petersen.

I thought this rumination from Jay Caspian Kang on “antiracist” children’s books was very interesting. Kang’s clearly thinking out loud here about the intersection of books as moral instruction, and books as aesthetic experiences. For what it’s worth, I think children are entitled to art as much as anyone else, but we also have a long way to go until all children have access to quality books that speak to their lives. I feel a future column coming on.

Numerous imitators have cropped up over the years, but The Millions is the grandparent of all “Most Anticipated” books list. They have their first-half of 2022 preview up for your perusing pleasure.

If you’re looking for more insights into the trauma plot, check out this long exploration from Brandon Taylor, author of Booker Prize nominated novel, Real Life.

Here’s an interesting read from Amanda Hess about another trend in narrative, the antiheroine mother who leaves her children.

Interested in “comic books for adults? The New York Public Library has 50 “new must reads.”

Recommendations

All books linked below and above are part of The Biblioracle Recommends bookshop at Bookshop.org. Affiliate income for purchases through the bookshop goes to Open Books in Chicago.

Solid start on affiliate income this year. Already at $15. Remember that I’ll match any total up to 5% of the annualized revenue for the newsletter or $500, whichever is larger as a donation to Open Books.

The list of 2022 recommendations will be filling up week by week.

After my earlier request the queue for recommendations filled up nicely, but don’t let that stop you from clicking below for instructions on how to get in your request.

1. The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles

2. Harlem Shuffle by Colson Whitehead

3. Rock Paper Scissors by Alice Feeney

4. Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

5. The Trees by Percival Everett

Kathleen F. - Asheville, NC

I may the last living person to have never read an Amor Towles book. Anyway, if Kathleen hasn’t read The Sellout by Paul Beatty, she’s in for a treat.

1. Stoner by John Williams

2. So Long, See You Later by William Maxwell

3. All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy

4. Anxious People by Frederick Bachman

5. Bewilderment by Richard Powers

Joe G. - Northbrook, IL

I kind of emotional aching is at the center of all of these books, though taking very different forms in each. For me, that brings to mind Stewart O’Nan’s Last Night at the Lobster.

1. Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr

2. To Paradise by Hanya Yanaghara

3. Arcadia by Iain Pears

4. Binding by Bridget Collins

5. The Book of Strange New Things by Michael Faber

Elizabeth A. - New Jersey

I want something with a bit of an otherworldly feel to match the way these authors stretch reality. I’m going with The Age of Miracles by Karen Thompson Walker.

1. Homeland Elegies by Ayad Akhtar

2. The 18th Abduction by James Patterson

3. Can Robots be Jewish? edited by Amy Schwartz

4. Finding Chika: A Little Girl, an Earthquake and the Making of a Family by Mitch Albom

5. Golem Girl by Riva Lehrer

Laura Z. - Buffalo Grove IL

I think Laura will be drawn into the mystery and mysteriousness of Hannah Pittard’s The Fates Will Find Their Way.

Paid subscription update

I really couldn’t be more excited and grateful for the initial response on my plea for paid subscriptions. One week in and we’re over 90% of the way to my end-of-year goal of $10,000 in annualized revenue, which was my personal threshold for believing there’s sufficient enthusiasm and support for me to keep doing this into the foreseeable future.

Of course, this now has me feeling a little excited for what else might be possible. Currently, just under 7% of subscribers are paying. If that number reaches 10%, I’ll be able to start soliciting additional content from a network of interesting and insightful writers. If you’ve read this far, maybe it’s worth a little somethin’ somethin’ ?

Could not be a worse weather day here in extremely not sunny South Carolina. A good reason to stay in and stay safe. Mrs. Biblioracle and I are going to finish watching what I think is one of the most successful book to television adaptations of recent memory, Station Eleven.

Take care,

John

The Biblioracle

I really liked your argument that the increase in the trauma talk - through our personal conversations and through literature - is in direct relation to the decline of the public institutions. They do have a comforting and community role, as you mention.

As I'm publishing here chapters of my self-growth memoir, which of course is filled with trauma, dissected and analyzed, it's interesting to read about the larger theme - why do we need to write so much about trauma? In my case, to offer inspiration and comfort to people going through similar events in their own lives.

Maybe we share our traumas to feel less alone.

Very well said John! Trauma is heavily emphasized in novels because it sells! It sells books, newspapers and magazines and satisfies a sad need for gratuitous thrills at someone else’s expense, be it fiction or nonfiction. I’m a retired mental health counselor and in my years of practice I have experienced so much secondary trauma listening to the heartbreaking lives of clients that I have no need to read about it for”pleasure.” I believe it is also reflective of the cultural breakdowns you mentioned, as well as a deep societal sense of isolation of the soul. I hope as we eventually come out of the pandemic our thirst for trauma will subside and our mental health improves. Authors, please pay attention!