I think it’s easy to forget what a phenomenon the Harry Potter series was.

I’ve been thinking about this more in the context of my Chicago Tribune column from two weeks ago in which I observed that when I was teaching the 2000 to 2010 era, it was a virtual guarantee that my college students had read a book (or books) under their own initiative, the books being Harry Potter.

I actually have a vivid memory of the release of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix in 2003, the 5th book in the series. This was the first book to come out after the start of the film franchise and was hotly anticipated in ways the previous books didn’t quite reach. At the time my wife an I were living in Blacksburg, Virginia while she did her residency in small animal internal medicine at Virginia Tech. I’d gotten into the habit of doing my grocery shopping one of two times to avoid any crowds, one was during Virginia Tech Hokies football games when the entire town (except me and the skeleton crew at the Kroger) were at the stadium. I recall they used to play the game over the store P.A. in case any poor sucker who cared about it found themselves in the store.

(I did not care.)

The other time was between 9 and 10pm, the hour before closing. One night, as I arrived at the store, I noticed the parking lot was nearly filled dozens of people lined up outside. As I got out of my car and approached the entrance, a grocery store employee with a megaphone said that people who wanted to buy books should get at the end of the line. People getting groceries could come right in.

Once inside, I saw what the shoppers were waiting for, giant shrink-wrapped pallets of hardcover copies of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix lined the aisles. The book was going on sale at midnight and Kroger would be staying open to accommodate the people who did not want to wait to get their hands on a copy.

This was a grocery store, not a bookstore, and they looked prepared to sell at least 1000 copies of the book. I did a little googling to check my memory and according to the New York Times, the book sold five million copies in the first day. This can only happen when your book is not only selling at Barnes & Noble and Amazon, but your local grocery store as well.

I was teaching a summer school public speaking course at the time and when I got to class the next day half a dozen or more students were reading the book at their desks before class started. Judging from their progress, some of them must’ve been up all night. They would’ve been in the sweet spot, age-wise for Harry Potter, the first book coming out when they were in grade school. I might’ve been a little jealous. I’d love a lot of books as a kid, but never experience millions of other kids loving the same books alongside me.

It’s interesting to consider the confluence of factors that led to such a phenomenon. Other books had become must reads before, achieving a kind of cultural momentum that puts them in the hands of people who normally don’t truck with books. I’ve always been fascinated with the story of the book, Jonathan Livingston Seagull, a book literally told from the perspective of a seagull that was published in 1970 and through word-of-mouth over time arrived at the top of the New York Times best seller list where it stayed from July 2, 1972 to March 18, 1973.

Harry Potter had the benefit of coming into the world during the Internet 1.0 period, where word-of-mouth could spread much more quickly via digital channels than previously, but also before networks were increasingly fragmented, different people congregating in different niches as is the case these days. The online fan fiction community also obviously gave a huge boost to the series as fans took Rowling’s characters and endlessly remade and remixed the stories for the enjoyment of other fans. The more intimately you knew the originals, the more you could enjoy the various derivative stories.

Do you want Hermione to end up with Harry rather than Ron? That’s covered. How about Harry and Draco Malfoy having a secret romance? That’s covered too. With readily accessible online gathering spaces, the Potter fandom could find each other in ways that had never been possible before.

Jonathan Livingston Seagull has reportedly sold 44 million copies, more than To Kill a Mockingbird (40 million), but fewer than Watership Down (50 million). This still seems bizarre for a book that I have to believe is barely read today. If that sounds like a lot, consider that the Harry Potter series has sold over 600 million copies, with the first book, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, moving 120 million copies all by itself.

There is no requirement for a book to be “good” in order to become a word-of-mouth cultural phenomenon. While recognizing these things are always subjective, it’s pretty clear that Jonathan Livingston Seagull is not a particularly good book. Truthfully, it’s actually quite bad, but clearly something must have resonated to keep it aloft on the best seller list for so long.

The Harry Potter books are not “bad,” but it is a stretch to believe that the series’s massive sales totals are due to it being uniquely “good.” I have read the first and sixth volumes of the series and found book one to be above average kids fiction and book six to be a bit of a slog that I started to skim to find out what would happen. I share this not as a definitive critical take on the quality of these books, but simply as an observation by someone too old to be seduced by Harry Potter when it first arrived, and perhaps too jaded to give myself over to the pleasures its fans treasure.

I have seen all the movies, so I’m versed in the story and obviously was hooked enough by the tale to see it to the end in that form.

My opinion aligns well with Ursula K. Le Guin’s assessment, who when asked about Harry Potter replied, “I have no great opinion of it. When so many adult critics were carrying on about the ‘incredible originality’ of the first Harry Potter book, I read it to find out what the fuss was about, and remained somewhat puzzled; it seemed a lively kid’s fantasy crossed with a ‘school novel’, good fare for its age group, but stylistically ordinary, imaginatively derivative, and ethically rather mean-spirited.”

This comes off as a bit more dismissive than I think it was intended, but IMO, there’s not much to argue with here, particularly that last part, “ethically rather mean-spirited.” The ways that Rowling’s characters are made to suffer sometimes seem to have no meaning other than to portray suffering and strike me as manipulative. Unlike Le Guin, whose fantasy work often dealt with thorny philosophical and moral questions embedded in compelling stories, there does not appear to be a larger coherent philosophy to the Harry Potter universe. Stuff happens, then more stuff happens until it stops happening.

I didn’t set out to rain on any Harry Potter fans parades and having witnessed the fanaticism of my traditional college-age students for books they’d first connected to as children, I do not gainsay the books’ potency, except to say what I came here to discuss, which is there’s a superior series of fantasy novels for young readers that I wish more people knew about.

Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising series features an eleven-year-old protagonist (Will Stanton) who, on his birthday, discovers his predestined role as a central figure in an eternal fight between the forces of the light and dark in the realm of magic. In this battle he is joined by a group of siblings (the Drew family) who have important roles to fill as part of the largest quest, and is guided by an old, wise mentor (Merriman Lyon) who is enormously powerful, but cannot intervene in tasks that belong to Will Stanton alone.

In order to ultimately defeat the forces of the dark, those of the light must gather a series of objects, “the things of power” in order to muster all the good magic energy that will be necessary for the final battle.

The story parallels to Harry Potter are not an indicator that Harry Potter is derivative of The Dark Is Rising, but rather both series are making use of well-worn and effective tropes with a quest story structure. The Dark Is Rising is inspired by English, Norse, and Celtic folklore which inspires like, every adventure story that has ever come after. The character of Merriman is literally Merlin in an earlier story timeline, and the Arthurian legend is a kind of overlay for the entire series.

As Le Guin observed Harry Potter is a kind of remix of narrative elements that proven enduring and popular, and part of what makes the series work on audiences it a sense of familiarity. These are stories we’ve heard many times.

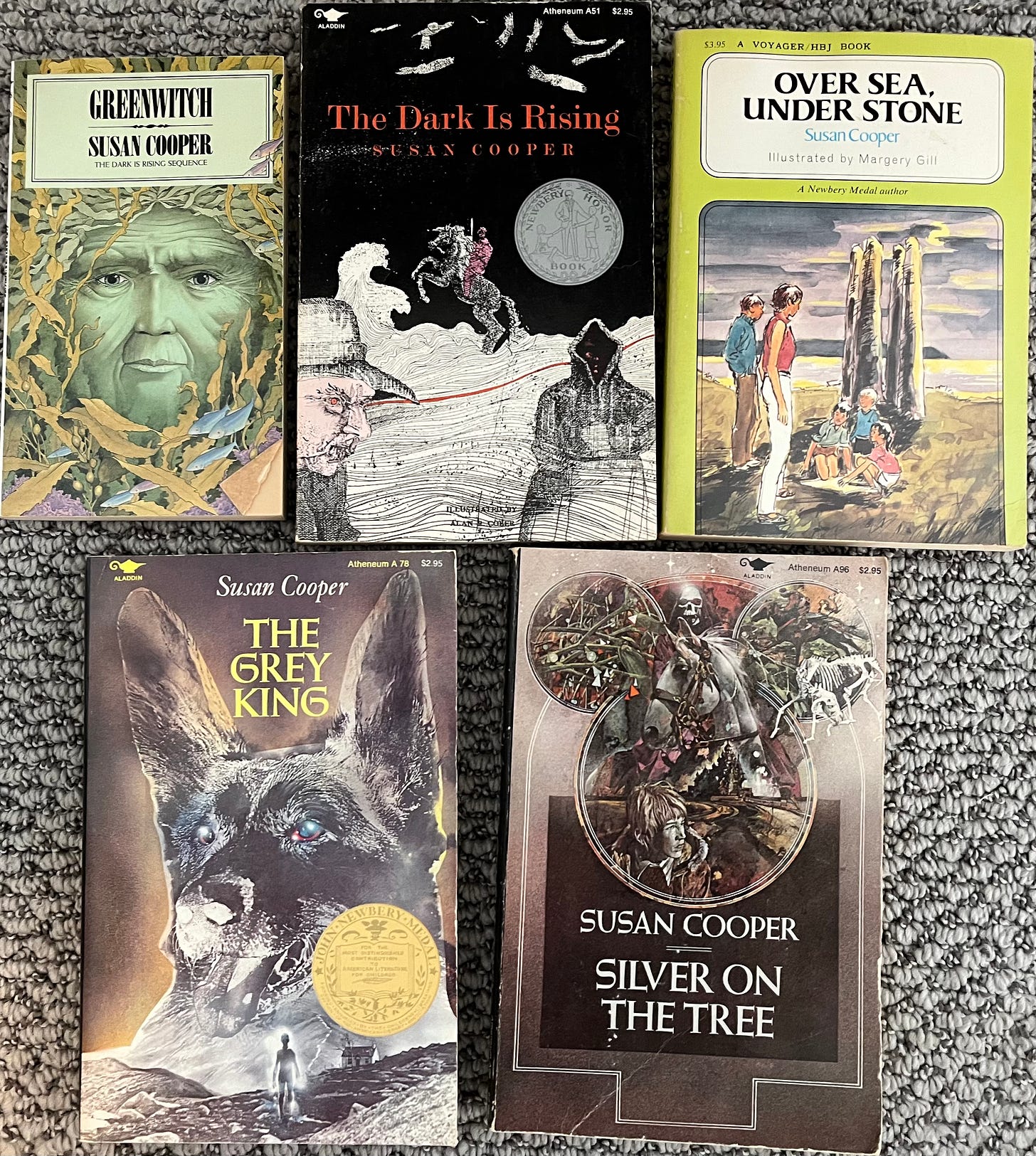

As you can probably tell in the picture above, with the exception of Greenwich, those are the copies of the books I read as a child. The first in the series, Over Sea, Under Stone was published initially as a stand alone book in 1965, with The Dark is Rising kicking off the final four volumes in 1973.

The books were highly acclaimed at the time, with The Grey King winning the Newberry Medal in 1975.

I probably read each book half a dozen times when I was young, relishing the chance to return to a favorite story. Altogether, the five books are about the length of the longest Potter book (The Order of the Phoenix) and the storytelling benefits from it in terms of momentum. Harry Potter ends up as a kind of open universe video game, larded with endless side quests, which may be individually satisfying, but when everyone knows that the showdown with the Big Bad is coming eventually, you begin to wonder what’s taking so long. Large swaths of the later Potter books are about filling in a larger backstory and mythology, elements the fandom loves, for sure, but I think even the hardest dying fans will admit to some storytelling bloat.

The Dark Is Rising also benefits from Cooper’s superior prose, never Rowling’s strong suit. The series benefits particularly because while there’s plenty of action in The Dark Is Rising, much of its power comes from Cooper’s ability to conjure truly spooky atmospherics.

Here's a paragraph from the first page of The Dark Is Rising before anything is really happening, story-wise that still manages to set a mood that will pay off in a couple of pages:

The snow lay thin and apologetic over the world. That wide great sweep was the lawn, with the straggling trees of the orchard still dark beyond; the white squares were the roofs of the garges, the old barn, the rabbit hutches, the chicken coops. Further back there were only the flat fields of Dawsons’ Farm, dimly white-striped. All the bard sky was great, full of more snow that refused to fall. There was no color anywhere.

Bare and forbidding, a sky sky leaden with snow looming overhead. We learn just below this passage that it’s four days until Christmas, but the scene is not festive.

On the next page, the young hero, Will Stanton, will venture into this landscape with his brother James to feed the rabbits and acquire more hay from Dawsons’ Farm.

Each image previously established is disturbed by Cooper.

Normally, the rabbits “would be huddled sleepily in the corners” but this day, “they seemed restless and uneasy, rustling to and fro, banging against their wooden walls.” Will’s “favorite rabbit” who usually lets him scritch her behind the ears, “scuttled back from him and cringed in a corner, the pink-rimmed eyes staring up blank and terrified.”

A sense of the uncanny builds as the boys continue on to Dawsons’ Farm, and reading the opening chapter again for the purposes of writing this newsletter has me feeling the delicious stomach-lurching dread that worked its magic on me over forty years ago.

The books really are fantastic, and I’m guessing they’re still read some, pressed on children by Gen Xers like me, but they obviously don’t sell like Harry Potter. Part of the reason may be that the characters do not age up like those in Harry Potter, so the pubescent romance elements that comes to be a significant part of the HP series is absent. This is about kids on an adventure to save the world. They are wonderful books for young readers, and while I’ve re-read them with great appreciation as an adult, I would not confuse them with the YA crossover phenomenon that was so prominent for a while.

Part of it may also be the absolutely terrible film adaptation from 2007 (titled The Seeker in the U.S.) that seems like it was put into production in order to capitalize on Potter popularity, but in an effort to match the action-packed nature of the Potter films destroys what is most interesting about The Dark Is Rising in book form, those atmospherics and inner journey of Will Stanton.

Cooper was not happy with the alterations.

When it come to fantasy series for young readers, The Dark Is Rising is not as popular as The Chronicles of Narnia (120 million copies sold) or The Hobbit et al. (100 million copies sold), but it is absolutely their equal in terms of quality.

If you know a young reader and want to give them a book they might not know that is better than Harry Potter, you now know where to go.

(The entire boxed set of The Dark Is Rising Series is less than $40 at Bookshop. A serious bargain.)

Links

This week at the Chicago Tribune I join the calls for an FTC investigation of Amazon’s business practices, particularly the role they play in the overall books ecosystem.

Over at Esquire, Sophie Vershbow looks at the “broken blurb system.” Readers may recall that I shared my own dislike of blurbs in this space a few weeks ago.

Writing at The New Republic Annie Abrams’ Shortchanged: How Advanced Placement Cheats Students, Aaron Hanlon asks, “Are AP Classes a Waste of Time?” If the goal is learning stuff and stoking interest in intellectual pursuits, the answer is yes.

I thought this Fresh Air interview with Zadie Smith on her new book, The Fraud, was terrific.

From McSweeney’s this week in honor of just about everyone being back to school, “Universally Acknowledged Truths for High School Teachers” by Rebecca Turkewitz.

And in case you missed it Wednesday, we had our latest installment of books more people should know about.

Recommendations

1. Ioga by Emmanuel Carrère

2. Our Share of the Night by Mariana Enriquez

3. Art by Yasmina Reza

4. Diorama by Carol Bensimon

5. Pageboy by Elliot Page

Branca S. - Toronto, Canada

For Branca I’m recommending a novel about a woman’s search for herself that works its way under your skin: Vendela Vida’s Let the Northern Lights Erase Your Name.

Book Giveaway

I’ve been having a hard time getting the winners of the last two weeks’ giveaways to respond to claim their prizes, so I’m going to make sure that I can send those packages on their way before I add another to the queue. Be sure to keep an eye out for any email from this newsletter. You might be a winner!

Where are my fellow Susan Cooper fans at? Sound off in the comments.

See you all next week,

JW

The Biblioracle

Also worth mentioning is pretty much any of Diana Wynn Jones work. She’s got a mountain of incredible Ya fantasy, and even JK Rowling claimed to take inspiration from her.

You had me worried there for a moment--if you'd said that Seagull was the better book I would have had my faith in humanity shattered.

I am not sure that Cooper's series is all that great though. I re-read it not long ago and I think the prophetic narrative robs the protagonists of a lot of agency; they come off as rather passive and flat as a result.

For me the superior Chosen One YA is Lloyd Alexander's Prydain books partly because the protagonist has a real arc and makes painful choices and the supporting cast have vivid personalities. (The main flaw is that the major female character doesn't get a parallel developmental story alongside the male lead when that seems tantalizingly possible.)